Versión en español: https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.11083

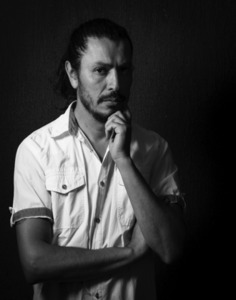

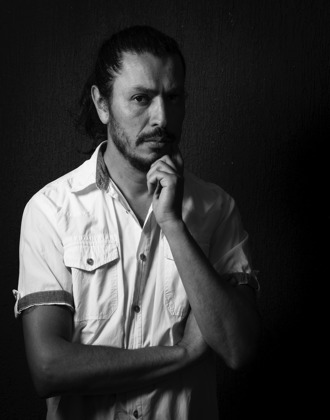

Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez is a filmmaker, image and object curator, professor, and artist from the indigenous Mapuche community in Chile. On March 27, 2019, he spoke at length from Concepción, Chile, via Zoom with Stephen N. Borunda, the coordinating editor of this journal. Journal coeditor Janet Walker also participated in the conversation. As with all of our contributors, Huichaqueo leads us in the inception of a broad, transdisciplinary dialogue among key actors and thinkers at the media-environment nexus.

It is our great pleasure to present the resulting conversation, conducted expressly for this “States of Media+Environment” stream and edited and translated from the Spanish by Borunda. In the course of the interview, Huichaqueo explains the historical context of his curatorial and film projects and their spiritual, cosmological, and environmental concerns. We wish to express our gratitude to Huichaqueo for his generous participation and for providing links to his films. We thank Victoria Dastres Cárdenas for transcribing the original interview in Spanish.

Author’s Note: Just as this interview was about to go to press, mass protests started in Chile against neoliberalism, social inequality, and government abuses. Huichaqueo has enthusiastically witnessed the legitimate claims made by el pueblo Chilenx across the country and the surge of artistry in the protests; his interview with us shows tremendous foresight for these recent events. Huichaqueo has been active in the protests, and during a recent talk published by the newspaper El Mostrador he helped articulate the roles of Mapuches and artists assisting in healing social wounds. We send our strong support to el pueblo Chilenx and their courageous efforts.

Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez: I am a forty-one-year-old with a Mapuche father and a Chilean mother. I am from southern Chile—which is indigenous territory. I was not raised around the Mapuche culture due to the oppression our community faced under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. My return to the indigenous was later, a common phenomenon for many in my generation.

While I was born during the climax of the military dictatorship, there were other military dictators before Pinochet. When the Republic of Chile started, that, too, was a dictatorship—a dictatorship that attempted to crush the indigenous worlds of the territory. Even preceding that period, there were also three hundred years of war between the Mapuche world and the Spanish crown. During these times, we had a unique art of war, and male warriors such as Leftraro and female warriors such as Janequeo led us. The history of these events as written in Spanish memoirs names only men. But, in our accounts, there are female warriors—and many of them. The sexes are always balanced. The feminine and the masculine complement one another. There is not one without the other. Masculine and feminine spirits must both flourish naturally . . .

Stephen N. Borunda: Thank you for that introduction, which provides us with some of the historical contexts for your community and your work. You spoke of the various dictatorships in Chile, and, obviously, today there is still a great deal of tension between the Chilean government and the Mapuche community. In interviews elsewhere, you have even said that Chileans and Mapuches are from different worlds (Aguirre 2016). Certainly, part of those differences stems from Chile’s role as an “extractive state,” which thinkers like Aníbal Quijano (2007) and Walter Mignolo (2011) would likely see as part of “coloniality” or the “colonial matrix of power.” How would you describe these two worlds, and can you find any reason for future optimism?

FHP: I recall that in one interview, I talked about my exhibition called Portal de luz (Portal of Light), which in Mapudungun is Wenu Pelon. It is an exhibition [within the Museo de Artes Visuales] that I made to foster an urgent dialogue between the Chilean world—the dominant, Eurocentric culture in this country—and the ancestral Mapuche world. Currently, there is very little communication between these worlds; there is practically an internal war within the country. The dominant powers here try to confuse [matters]. Information is manipulated about who the Mapuches really are, even though most all of us are related by blood—as exemplified by my mestiza mother. The dominant powers say, “No, here are white Chileans and over there are indigenous people.” The syncretism and blends of both people and cultures within Chile are ignored . . . For this reason, the Chilean family is sick since there is no dialogue about such matters. The white/indigenous binary ignores the beautiful and intricate mestizaje that constitutes this country, leading to absurd conflicts and general societal ignorance.

Racism, symbolic racism, and symbolic exclusion in popular accounts put the Mapuches and others in a minimized social state. Indigenous communities throughout the world are always imagined as both injured and inhabiting all the evils of the world. Within Chile, these lies apply to the Mapuches. Why the Mapuches? Our blood carries a spirit of intrinsic freedom since we never lost our liberty to Spain, which was a different situation from that of many other indigenous peoples [in Latin America] . . . We are a people who have answered countless challenges with talent and intelligence; we foster ways of life that seek balance with nature. The dominant Chilean culture does not like this, does not accept this, and does not want this. They have used every strategy against us for about two hundred years . . . Prior to this current oppression under Chile, even the Spanish crown eventually recognized the Mapuche world as a nation . . . But when the Republic of Chile arrived on the scene, they betrayed previous treaties with deception, war, and violent technology. At that moment, the percussion submachine gun was used, I believe. This weapon was also used in the attempt to exterminate Native American communities in the US around the same time . . .

To answer your question a bit more directly, within this recent history of pain and the militarization of our territories, Francisco Huichaqueo enters this world. I left home to study visual arts and then documentary cinema . . . Years later, I was invited to do an exhibition in the Museo de Artes Visuales in Santiago, where our sacred cultural items were held. These items were likely taken during the looting that took place during the Campaign of Pacification of Araucanía. One hundred and something years after these thefts, we were called to return, to touch that which belonged to us: ceremonial objects and both traditional and religious pieces of clothing. Life put me in a situation, a very spiritual situation, to be able to work with what is ours. I saw this as a remarkable opportunity but, more importantly, a spiritual mission. Advised by a machi (a Mapuche female shaman), I directed that exhibition and the accompanying works of cinema not in an occidental way, but following a Mapuche indigenous spiritual path. Wise men and women in our community advised me that if I followed that path of ancestral wisdom, we would have a healthy way to open a loving dialogue between the Chilean and Mapuche worlds. We have done that. The exhibition was supposed to be open for only two years, but it has now been open for four years. They cannot close the exhibit because it is filled with important spiritual energy. The exhibit now is Mapuche territory. It is not an exhibit of contemporary art but a place where prayers are made to the Great Spirit. It is a place where the people of Chile and the Mapuche worlds can find one another and talk so Chileans might empty themselves of their ignorance.

SNB: Thank you for walking us through the inspirations behind your important curatorial work. You are also a filmmaker. Scholars such as John Durham Peters in his book The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (2016) call for a new philosophy of media that allows us to recognize how nature, as well as mechanical and electronic communicative and inscriptive devices, acts as media. You spoke about how the Mapuche community seeks a lifestyle in balance with nature, and your films, obviously, deal very intimately with the impacts of the environmental imbalances that constitute the Anthropocene. Can you speak a bit further about the lines of connectivity between nature and your own film theories?

FHP: I must first say that my philosophy is not only mine—it comes from a collective. I, as a filmmaker, can illuminate certain things, improve or refine certain concepts and ideas or slightly expand them to this modern world, but the essence of these theories is ancient—millenniums old. We have a philosophy called kimün. Kimün is the form of philosophical, spiritual thinking of ancient Mapuche thought that lives in us . . . Knowledge, after all, is transferred through the power of the word, through us, through stories and ancestrally by the pewma—the dream that reveals knowledge by bringing us to other places . . . In the human body, we naturally have a special engine that can bring us into contact with ancient knowledge . . . We have to speak and share this knowledge so that it does not get lost. From there, we can expand, feed, and better our spiritual thinking as a cooperative. That’s why, in one of my museum exhibitions, I put a simple label that says, “The spiritual instinct before reason.” The soul has an eye, a natural, instinctive spiritual perspective. Humanity must always place the spiritual before any sort of “logic.”

That’s why I have always loved observing and learning, as do all the Mapuches. We love to gaze, to look at nature and the horizon. In our dreams, we voyage, and we might go elsewhere. We might look from above, from under the water, from under the earth, from inside of a tree, from within the air, or from within the currents of a river. Many years ago, I worked in my father’s garden with him. I remember that when I was a child, I liked observing, preparing the earth, and planting. Years later, when I went to the university to study arts, I realized that my films had started in childhood, with the ancestral practice of tending the garden. So, for that reason, I like the cinema, to record life with this Western tool. Like the horse that brought Spain to the Mapuche world, we use the camera as an instrument of war. While we used the horse as a tool for battle, it was the horse’s strong and elevated spirit that helped us to coexist and heal our souls. Just as in the past, we learned to ride the Western horse, to become elite riders, I think the camera today is the modern horse for us. We must capture the imagery of our perspective, our cosmovision, and our understanding of life . . .

Janet Walker: Your description of how the Mapuche pewma enables travel through space seems to provide insight into the positioning of the camera in your films. We observe many shots from under the water and flying through the air.

FHP: Absolutely. Only half of a person exists on the tangible plane. The other halves of our bodies exist on another plane—the spiritual plane. There we can travel through a flowing medium. This more spiritual perception of nature and time allows us to access the ability to travel more so than perhaps another person who has a different, more materialistic, cultural structure. For that reason, perception is essential for us. When we are sleepy but not yet dreaming, we can use this physical gift to ask to go to other spaces. There we can perceive, in parallel, various landscapes—the political landscape, the spiritual landscape, and natural landscape in novel ways. There are many more planes than just this tangible, physical one—many more . . . In a meditative state, our soul can take flight . . . You can fly in the air, but it is as if you were under the water because your spirit captures a different energy field inside of this flowing medium. When you awake, you are exhausted. For that reason, the Mapuche perspective is generally from above . . . I have been invited as a filmmaker to document this journey. I fix the camera in front of life so life may enter through the camera. This spiritual water flows over and under the lens. My camera seeks to allow audience members access to the dreams I mentioned; my camera acts as a mirror into other dimensions. For instance, one day I dreamed that I flew through a small river. So the next day I put a camera into a beautiful river. I tried to create a portrait of what I had seen during the dream; I was obeying the script that came to me from this spiritual plane. The revelations from that space are also from life or your life that has manifested there . . .

SNB: Does this spiritual experience facilitate entrance into other times as well?

FHP: Yes . . . We are currently here, but we can travel to other points in space-time. Let me tell you about a terrible and wonderful experience with soldiers in southern Chile that had invaded an indigenous community. A friend of mine, a political prisoner, had just come out of prison. That day the longko, the Mapuche community leader, said: "Over there is the place where I used to play as a child. Let us go and play the ancestral game called palín as we wait together to greet the freed prisoner . . . " So many Mapuches walked with our flags, and we decided to take the territory symbolically. The whole day, there was a military helicopter looking down on us. There was no violence from our end, but they still felt the need to have a military presence . . .

Later that night, there was a full moon. We had gotten into a truck, and we were driving on an extremely bumpy stone road. Suddenly, the truck stopped shaking, and there was a feeling that we went to another space, that we had gone to an earlier point in time… I looked at my friends, and they appeared as my relatives from three hundred years ago. Our spirits were so strong in this moment that we went to another point in time in the past while also remaining in the same place. We all looked at each other, and we were our ancestors, all dressed in traditional garb. It was beautiful—just the full moon, the night, and the silent truck. There was only silence and the wind in our hair. In the Mapuche world, there are these magnetic forces that can be in a thought and . . . suddenly pass you to another space. Their name in Mapudungun is perimontun. This means a revelation, but it can also be an apparition. When that apparition appears you can go . . . and use the apparition as a time tunnel. This sort of dream traveling is quite common and resembles passing into and out of a drop of water.

SNB: Are there ways through which you have been able to incorporate the perimontun into your films?

FHP: This has certainly been my desire, and I pray to do this when I’m filming. I try to capture that special energy on film. So that after spectators see one of my movies, they can travel to these dream planes by themselves. It’s my wish. Some people, but not all, have told me that this happens to them when they watch my films. I believe that the people who enter these voyages have to be experiencing a unique vibration that day. I’m not sure I know the exact cause for this experience, but this is my goal. I think I have a long way to go as a filmmaker to cause that type of experience to be mediated through films. I hope that spectators have this Mapuche spiritual experience and that they are transported to that other space, whatever that space may be.

Film critics or scholars say that this is experimental cinema. I do not make experimental cinema. This is Mapuche cinema.

JW: In addition to these spiritual elements, your works also have a distinct tangibility to them that reflects the concerns of today—the current environmental crises, for example. Can you further explain how things from the material world figure into your films?

FHP: I am thinking of my film Mencer: Ñi Pewma, which I believe is one of my most political and spiritual films . . . Of course, I live in this moment in time, but it’s all the same. We must understand that the violence inflicted on us in our story, it is the same story one hundred, two hundred years ago. It is the same. This is the story of the breaking of the equilibrium of humanity, of humans who are urgently trying to return to having a balanced relationship with nature once again because we have already lost so much. Mencer means the spirit of sadness—and that meaning was revealed to me in the dream. I saw that word in my dreams, and I used it—the spirit of ancestral sadness. The spirit of the sadness comes from my father, from my grandfather, from my great-grandmother, from many years ago. This spirit comes at this time to show its presence as mediated through my film. The sadness of the Mapuche indigenous world and other peoples is shown on-screen. I seek to convey our heritage in the cinematic image—who we were, who we are, and who we will become. I seek to open doors to a new journey—a journey to other spaces and other times.

JW: Macarena Gómez-Barris wrote about Mencer in her book The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (2017). When you speak of the violence that the Mapuche community has faced, I am reminded of her discussion of how “false news” in mainstream media criminalizes Mapuches, Mapuche activism, and your defense of the lands and the waters . . .

FHP: Yes, this is our daily life. The media powers in Chile always side with business interests. The business owners with their ambitions need to have an enemy, and that enemy is indigenous societies because the forestry corporations and mining interests are based in indigenous territories. This generates an internal war, and we are transformed into the antagonists in the eyes of the public because of media reports about us when we are simply trying to protect our homeland. It is horrible. Businesses have been backed by armed police forces and the army to safeguard the hegemonic interests of capital.

Just to build on that, some time ago, we had won certain territorial demands . . . The corporate news stations fabricated some story about violence on our part, and there was some kind of montage that cycled on the news, just showing the false reports that Macarena describes very well in her book. These false reports are everywhere: in newspapers, on the Internet, and on television. Mapuches are always depicted as troublemakers who are fighting to get “everything for free,” when we are fighting for what is properly ours . . . They even invented the antiterrorist law so that Mapuches deemed to be a threat by the military could be easily imprisoned . . . These violent laws have caused the deaths of many Mapuches, the most recent victim being Camilo Catrillanca . . .[1]

SNB: We acknowledge what you have shared with us. Thank you for your time and important words today, Francisco. You have left us with much to ponder. As we conclude the interview, do you have some final thoughts that you would like to offer to scholars and students of media, indigenous, or environmental studies? Can you speak specifically about what are or should be the roles of media in a world of socio-ecological crises, and how media are approaching and reconstituting those roles? How are politically active communities of resistance adopting and engaging with media?

FHP: I think we are living in a time with so many tools that are favorable for our purposes. The Europeans brought the horse, the technology of that time, to these lands. So, too, with the technology of today—if we know how to use it well—we can communicate with one another and relay to the world what is happening to us. We can document and denounce abuses happening to humans across the globe. I do not speak only of indigenous groups; I am speaking about the human rights abuses occurring around the world, and this tremendous abuse has much to do with the machinery of extraction that now exists on a global scale. Consequently, Abya Yala[2] is in horrible condition. We see pollution in the Amazon, in the waters of southern Chile, and in the Mapuche countryside—where there are thousands and thousands of hectares of forest that are now under attack. So if we use the tool of the camera, and if we use it well, I think we can make a great show of strength. I believe that we have made a show of force through the documentary of denunciation, art, writing, and politics. That’s why in Latinoamérica and Chile, specifically, we have so many indigenous film festivals with very little money but a tremendous amount of heart. We show our realities because we also have to fight against that enemy called capitalistic consumption that trains people and makes them ignorant and unreflective . . . This is all so different from our world. In our world, we have a reason to live—that reason to live is to maintain equilibrium and care for the world around us.

Through the camera, I seek to mediate the beauty and grandeur of a river, or the sound of a bird in the morning, or the morning fog—the wealth that you cannot buy anywhere. Movies, songs, or stories that follow similar paths enlighten the soul, I believe. These sorts of projects seek to marginalize ignorance so that people can see reality. Hopefully, all people can then adhere to these values and recognize that they are also indigenous to this world. Being indigenous is not only blood. We have to see that every person on the planet is indigenous to the earth. We are one people—the great tribe. So with my works, I invite you all to be indigenous. Look for this tribe and create a pact with all—a pact grounded in spirituality that will allow for all of mankind to reach equilibrium among ourselves and with nature. Those are the thoughts that I wanted to share with you all, and I hope these words enter the hearts of both scholars and students.

Filmography

Che Uñum - Gente pájaro [Che Uñum - Bird People]. 2007. Directed by Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez. Chile.

Ilwen, la tierra tiene olor a padre [Ilwen, the Earth Smells of Father]. 2013. Directed by Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez. Chile.

Kalül Trawün [Reunion of the Body]. 2012. Directed by Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez. Chile.

Kütral Kürruf Mew - El fuego en el aire [The Fire in the Air]. 2017. Directed by Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez. Chile.

Mencer: Ñi Pewma [Mencer: A Bad Dream]. 2011. Directed by Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez. Chile.

Francisco Huichaqueo Pérez was born in Valdivia in southern Chile in 1977. He is a visual artist, filmmaker, and professor at the School of Visual Arts at the University of Concepción. He currently leads the First Nations portion of the Festival Internacional de Cine de Valdivia. His video installations, film documentaries, and film essays focus on themes central to his Mapuche heritage. In his oeuvre, Huichaqueo addresses the social landscape, history, culture, and cosmovision of his people. His audiovisual work has been exhibited at various indigenous film festivals such as ImagineNATIVE, in Toronto; the Museo Arqueológico de Santiago; and the National Museum of the American Indian, in Washington, DC. He has also held residencies in film and art in Taiwan and France. His work has been exhibited in Chile, France, Canada, Germany, the United States, Spain, Italy, Argentina, and Bolivia.

A Mapuche activist from Ercilla, Chile, Catrillanca came from a respected family of important Mapuche leaders. On November 14, 2018, he was murdered by a special police operations group of carabineros (police officers) called Comando Jungla. His murder has prompted demonstrations and protests throughout Chile.

A term originally used for the Americas by the Guna people; other indigenous communities have also recently adopted the term.

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)