The visibility of petroleum is highly uneven. Despite its ubiquity and foundational role in twentieth- and twenty-first-century modernity, oil can remain obscured or hidden: it was formed from the decay of infinitesimally small living organisms over a time span inconceivable in human terms, and it is extracted from deep below the earth’s surface. Even for local inhabitants and workers (and documentary filmmakers) in close proximity to oil extraction, it is often only the physical and social infrastructures, the surface indexical traces of petroleum, that are normally visible, until its hazards begin to take a toll on their bodies and environment. Consequently, animation has frequently been used as a distinctive tool to visualize oil, its extractive processes, their products, and their pasts and futures. Petroleum industries have embraced the capacity of animation to compress and expand time and space; simplify, abstract, and animate processes; and provide metaphoric and metonymic substitution. Through this, animation has become an integral part of the way oil companies have negotiated their relationships with governments, shareholders, and the public.

This article will examine animated films produced in Britain for oil companies in the mid-twentieth century and their representation of, and contribution to, the international and transnational geography of petroleum extraction. Within these films, the graphic basis of hand-drawn animation meant it was often used to display and propel into motion cartographic and diagrammatic representations derived from a range of disciplinary and intermedial contexts, which served to navigate and construct spatial and power relationships around oil industries. As a form of “useful cinema” (Acland and Wasson 2011), these films not only represented the geography of petroleum extraction onscreen, but similarly, their production, distribution, and exhibition were increasingly globalized. Diverse creative teams were formed through migration and exile; the films’ midcentury modernist aesthetics incorporated varied influences; the films were consumed internationally in film festivals, government departments, company branch offices, and shareholder meetings. Animation production was both enabler and product of the changing geography of petroleum extraction in the twentieth century.

The primary case study film discussed here, Full Circle, released in 1953 by British Petroleum (BP),[1] amply demonstrates these characteristics and the ways animation represented and created the spaces and places of oil. Yet Full Circle also documents a unique moment in the changing (post)colonial contexts of petroleum extraction. In production between 1951 and 1953, the film underwent considerable changes that reflected the political upheaval in Iran in this period. In March 1951, shortly after the film began production, the Iranian Majlis (Parliament) passed legislation to nationalize the oil industry. Although this action was disputed by AIOC and the British government, by October 1951 all British oil workers had been ejected from extraction and refinery facilities, and AIOC was cut off from its primary source of crude oil. In August 1953 an American- and British-supported coup resulted in the establishment of an administration favorable to foreign interests in oil extraction in Iran; however, by this time, Full Circle had been completed and released. Production materials for Full Circle held at the BP Archive (Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick) provide a unique insight into the way this animated film changed during these events and how it became a central tool for oil company and government deliberation on their relationship with Iran and other oil-rich states. While this case study approach is necessary for historical and subject specificity, the points raised here will be applicable to a much wider range of “petrocinema” (Dahlquist and Vonderau 2021b) and should be considered a model for more extensive study of animation in oil extraction films. As such, this article recognizes the importance of animation at the intersection of three fields of study: environmental and energy humanities;[2] useful cinema;[3] and animated documentary.[4]

The international dimensions of oil industry animation in postwar Britain

The animation and oil industries developed in parallel in the early twentieth century, and connections between them are evident from the silent era. British petroleum companies saw the power of animation to reach consumers in advertising—for example, in Mr…Goes Motoring (1925), a film made for Shell that animated drawings by famed cartoonist H. M. Bateman (Jackson 2019). In contrast to these familiar character-based approaches, the graphic capacity of animation to explain and direct was utilized by APOC—for example, In the Land of the Shah (1926), which featured animated maps to contextualize the documentary footage of Iran in the rest of the film. The Shell Film Unit, formed in 1934, is widely recognized as a central part of the British documentary film movement (Swann 1989; Russell and Taylor 2010); however, less acknowledgment is given to the extensive animation work undertaken under Francis Rodker, director of animation and special effects for the unit, both as inserts into live-action films and for self-contained animated films. In many cases, such uses were linked to prior intermedial graphic representation already in use within extractive industries and expert disciplinary fields, such as geology, engineering, or chemistry. Shell films such as Lubrication of the Petrol Engine (1937) or the Gasoline series with entries on Cracking and Octane (both 1948) include animated diagrams produced by Rodker that were fundamental to their utility and pedagogy (Price 2019).

Of particular importance to the discussion in this article, in the 1950s BP/AIOC invested significantly in a series of films by two London-based animation studios: Halas and Batchelor, and W.M. Larkins.[5] BP/AIOC films with contributions by W.M. Larkins included Distillation of Oil (1950, in four parts), Modern Oil Refinery (1951), and Chemistry of Oil (1955), in which predominantly diagrammatic animation sits alongside photographic material of oil infrastructure and processes. Halas and Batchelor had established a reputation with their wartime work for the Ministry of Information, and they were in production on the feature-length Animal Farm (1954) at the same time as they were commissioned by BP/AIOC to make wholly animated films, such as those that recounted petroleum-related histories: oil tankers, in We’ve Come a Long Way (1952); motor cars, in Moving Spirit (1952); flight, in The Power to Fly (1953); lubricants, in Animal Vegetable Mineral (1955); farm equipment, in Speed to the Plough (1958); and energy itself, in The Energy Picture (1959). These films were more focused on the downstream and end-user consumption of oil products rather than extraction itself, and they were more lighthearted character-based films described in press as “education without tears” (BFI/HAB-1-27-2 Clipping from Teachers’ World 18 September 1964). However, the studio also made films that departed from this pattern, with As Old as the Hills (1950) and Down a Long Way (1954) including factually detailed accounts of oil formation and exploration/drilling supported by diagrammatic animation, and Service (1954) providing training for petrol station employees. Both studios produced similar films for other petroleum companies, such as Refinery at Work (1955) for Esso and The Paying Bay (1958) for Shell, both made by Halas and Batchelor, and Dream Sound (1958) for Shell, by W.M. Larkins. Larkins’s film Full Circle (1953) provides a useful case study and is the primary film discussed below, not only because of its unique and well-documented production history but also because it combines the two aesthetic approaches, covering both diagrammatic and cartoon elements to communicate an imaginative and enchanting engagement with the geography and political relationships of oil extraction. Studying such films as a form of useful cinema moves us beyond simply analyzing the representation of oil in narrative fiction, commonly addressed by petroculture studies, to demonstrate the way animation was directly and actively used by the agents of petromodernity.

As will be addressed further below, these films all represented and furthered the globalizing role oil has played in underpinning twentieth-century modernity, framed through the commercial and political demands of their sponsor. While these films ostensibly were made for a British oil company by British animation studios, the films’ production demonstrated this globalizing tendency in applied ways as their production and distribution exceeded national contexts. Animation directors Peter Sachs and John Halas (born János Halász) were European émigrés (Lloyd 2019; Halas 2006), as were composers Francis Chagrin and Mátyás Seiber (Scheding 2008; Frankel 1973). Their contribution as émigrés indicates the regular exchange of personnel and ideas operating across national borders at this time. In the absence of a strong domestic entertainment animation industry, and faced with stiff competition from dominant American studios, sponsored animation provided a crucial space for the internationalization and diversification of the British animation workforce, also extending to female animators such as Joy Batchelor, Irene Castellanos, Nancy Hanna, Vera Linnecar, Rosalie Marshall, and Alison de Vere (Stewart 2021). In turn, this international modernity supported the dissemination of a new aesthetic modernism. Most notably, Halas collaborated with László Moholy-Nagy in Hungary and London (Halas 2006, 81; Walker 2006, 112), and Sachs’s work on Full Circle shows a very strong influence of Cubism, Futurism, and other modernist movements.

The distribution of British oil industry films was internationally focused with varied target audiences. In common with other types of “films that work” (Hediger and Vonderau 2009), the meaning of these films is contingent on the wider film ecology in which they operated. As Elsaesser, Dahlquist and Vonderau, and others have noted, it is necessary to consider of such films who made them and to what purpose, how they served the sponsoring organizations, and how their meaning and archival functions may have changed over time (Elsaesser 2009, 23; Dahlquist and Vonderau 2021a, 5–6). BP/AIOC films were concurrently shown internally for employee instruction; incorporated into shareholder meetings to secure funding and management support (BP/33526 The Anglo-Iranian Oil Co.'s Film Show reprinted from The Petroleum Times 9 January 1953); distributed free of charge through the Petroleum Films Bureau for schools and other organizations with an educational remit (Russell and Taylor 2010, 25); translated and sent to overseas branches to develop company values and to be shown to local audiences (BP/183149 Letter to Morden from Tritton, 31 January 1951); entered into international film festivals, such as Venice, to win prestige and awards (Kinematograph Weekly 1955; Kinematograph Weekly 1956);[6] and screened theatrically and broadcast on television to subtly advertise the company and its activities (BP/33526 The Anglo-Iranian Oil Co.'s Film Show reprinted from The Petroleum Times 9 January 1953). Petroleum films were a major part of new distribution networks and audiences that operated in parallel with and distinct from the theatrical entertainment film, even while they occasionally intersected.

In short, British oil films in the 1950s had an international outlook in production, aesthetic model, and distribution channels. Many of these production and distribution characteristics were shared with the documentary films discussed by Damluji, Jacobson, Russell and Taylor, and others. However, animation also had unique characteristics and roles. The Petroleum Times report on a 1953 shareholder screening noted that “in a programme of documentary films [We’ve Come a Long Way] gave a light touch without departing from the main object, to instruct and interest the audience” thanks to its “Technicolor cartoon form” (BP/33526 The Anglo-Iranian Oil Co.'s Film Show). Different understandings of the specificities of animation and the balance between appealing, and often humorous, cartoon aesthetics against other more serious artistic or pedagogical modes played an important role in the production and reception of Full Circle. Likewise, the program for the 1956 shareholder screenings stated “films cannot look ahead,” which Jacobson interprets as both a cautionary statement to avoid making undeliverable promises to investors and a “truism” for documentary film that can only record what already exists to be filmed (Jacobson 2021, 282). However, the fantastical potential of animation meant it was free to imagine and visualize the future, a capability Full Circle and some other animated films embraced, especially in their picturing of new geographies of oil extraction.

Mapping and animating petroleum extraction

Animated maps have long been a commonplace component of nonfiction and documentary films, including those centered on petroleum industries. Contrasted with the densely textured and edited live-action footage that often surrounded them, the communicative method and purpose of animated maps may be mistaken for being self-evident in meaning. They do not utilize the sophisticated and eye-catching techniques of cartoon animation seen elsewhere, instead using dynamic versions of long-standing cartographic principles to represent, seemingly transparently, preexisting geography. Yet, as Priya Jaikumar has explored, such animated maps enact complex political functions. Examining colonial films made by Gaumont British Instructional in the 1930s that are closely related to the petroleum films discussed here, she finds they do not simply represent existing spaces but construct those spaces through their selective visualizing and framing: despite a commitment to “accuracy” by geographers, they entail a form of “imagination” (Jaikumar 2011, 172–76). This in turn raises broader debates in cartography, such as those John Pickles discusses in detail, recognizing that “maps and mappings precede the territory they ‘represent’” and thereby “provide the very conditions of possibility for the worlds we inhabit and the subjects we become” (Pickles 2004, 5).

A number of the 1950s BP/AIOC animated films raised above incorporate maps that are revealing of this construction of places. The Energy Picture, made by Halas and Batchelor for BP in 1959, narrates an account of the voracious demand for energy and makes a case for the need for ever larger oil pipelines and tankers to satisfy this. A highly stylized map (figure 1, The Energy Picture [1959]) animates a line growing over the extended route large tankers must take from the Middle East around the Cape of Africa to reach the United Kingdom. The large scale necessarily excludes any significant detail, and the map does not indicate any national borders or political organization of the space, presenting the issue as simply one of the physical logistics of oil distribution while eliding any question of ownership or sovereignty. As Old as the Hills, a 1950 Halas and Batchelor production for AIOC, begins with an image of a globe rotating on its stand (figure 2, As Old as the Hills [1950]). A repeated musical motif gives the impression of a squeaking joint in need of lubrication, which is supplied by oil being dropped from a spout onto the globe, quietening the sound, and accompanied by a voice-over stating, “every day the world uses oil.” Oil literally makes the world turn, but also silences the friction that occurs. Questions of national borders or difference are again omitted here, suggesting that the need for extraction and usage of energy derived from oil is universal and equitable. It even bypasses human agency as it is the earth itself that seems to consume oil, matching the rest of the film, in which no human figures are shown—rather, cars, ships, and factories consume oil of their own volition. Similar animated maps and globes are present in other BP/AIOC films including The Power to Fly and We’ve Come a Long Way. The control animation allows over mapped spaces matched the dominion over real-world geography oil companies hoped to achieve and normalize.

These examples largely remain within the intermedial conventions and practices of cartography, entailing the questions of accuracy, subjectivity, and intentional distortion that Pickles sees as recurring debates within his field (Pickles 2004, 32).[7] Yet, while Pickles is concerned with geography as a discipline and cartography as a method for it, he also opens his book with a provocative and expansive question prompted by Swedish geographer Gunnar Olsson: “‘What is geography if it is not the drawing and interpreting of a line?’. And what is the drawing of a line if it is not also the creation of new objects? Which lines we draw, how we draw them, the effects they have, and how they change are crucial questions” (Pickles 2004, 3). This might easily also be taken as a reflection on traditional hand-drawn animation. In this formulation, all two-dimensional animation, not just animated maps, can be understood to have a cartographic impulse in the process of drawing boundaries, defining “inside” and “outside,” and determining relationships between different spaces. An examination of the way animated films construct the space of petroleum extraction must not only address the conventional map inserts seen in films like AIOC’s Operations in South West Iran (1938) or The Third River (1955) but also encompass all animated representations of the spaces of extractive processes.

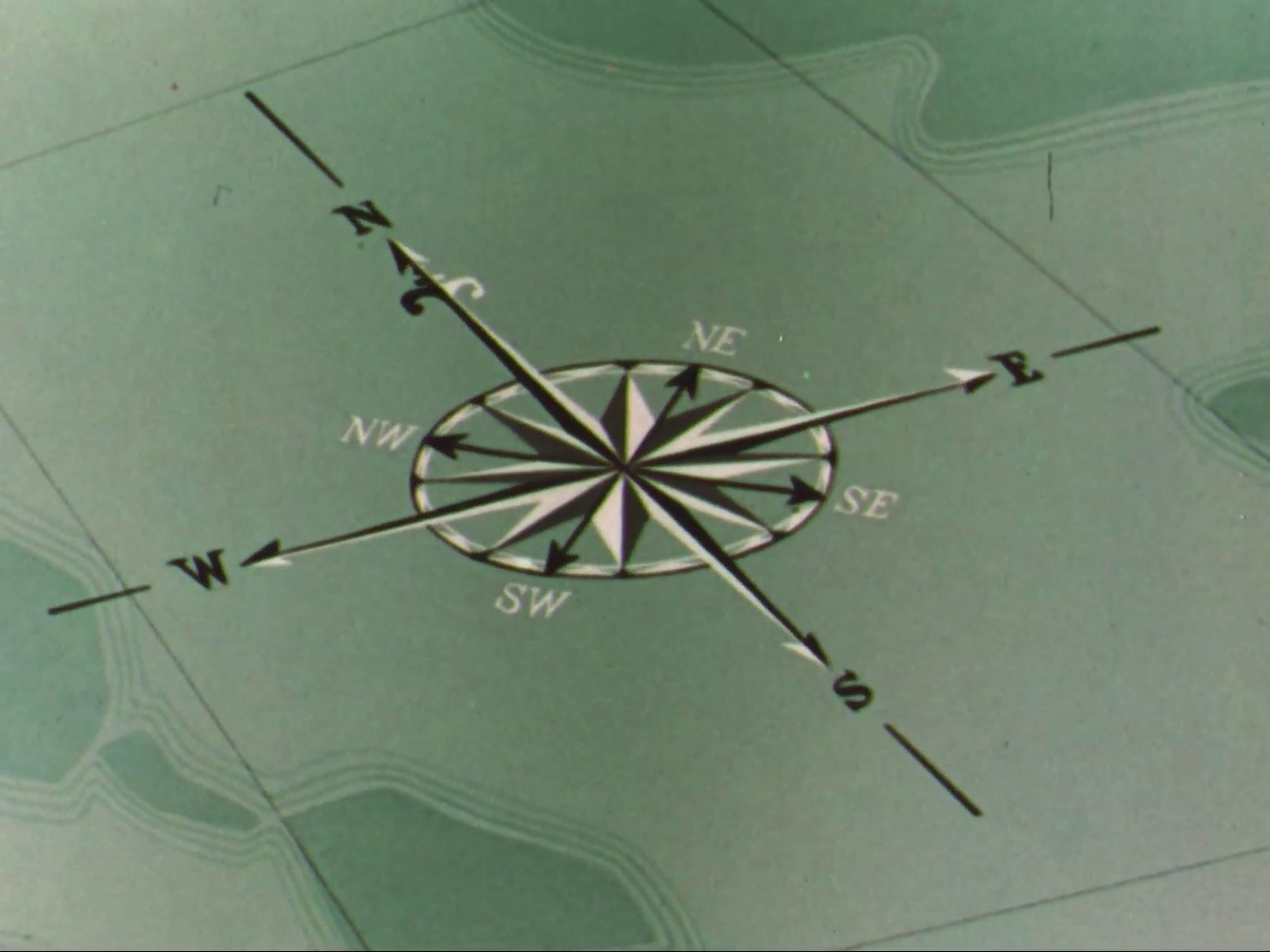

Full Circle presents a striking case study of this cartographic imagination of animation at the service of petroleum extraction. The title of the film, Full Circle, and its multiple meanings immediately signal the cartographic intent of the film. First and foremost, it describes a two-dimensional shape, indicating the graphic basis on which the film will build its arguments. Midway through the film, the circle is given explicit cartographic meaning as we are shown a circular compass rose on a map, with animated lines extending from it to indicate the different directions extracted oil travels from its source around the world (figure 3). This is facilitated by another physical form of circle as the map segues into a series of representations of transport and industrial activity dependent upon oil for propulsion: the propellers of an airplane, the rolling wheels of a truck, the speeding wheels of a train, the turning propeller of a large tanker, the turning cogs of a crane, the spinning bobbins of a cotton mill, the rotating caterpillar tracks of a plow (figure 4, Full Circle transport). From these physical circles arise the political ideas the film wants to put forward: the full circle of reciprocity between the country of origin of the extracted oil and the petroleum companies exploiting its potential. This is captured in abstracted wheels and cogs that feature both on the background of the main title card at the start of the film and midway through the film illustrating narration stating “throughout the world, those turning wheels are speeding production … and money is being spun” (figure 5, Full Circle wheels of production). This in turn propels the onward march of time and progress. The graphic understanding of the world brought about by animation is inextricable from the way the film constructs the physical space of the places it describes, and also the political and economic relationships between them.

Animating unseen and invisible extractive processes

Central to the message of Full Circle is the promise of a better future that oil, and the prosperity that comes with it, can bring to the countries that oil is extracted from. Here the cartographic imagination of animation finds its fullest expression as the film aims not only to represent existing places but also to envision the future modernity that oil will facilitate. The film opens with the BP shield house mark (logo) followed immediately by introductory title cards reading “As Man’s knowledge and skill have grown, so has grown his ability to win from deep within the earth ever more of the Energy which civilisation needs … Energy, when released and put to work, also creates wealth … the wealth so created can benefit the peoples of the lands beneath which Oil is found.” From this opening, the film establishes a dichotomy between an undeveloped, even atavistic, existing world and the civilization that petroleum extraction promises. In its phrasing, it frames nations as only surface-deep, as if a two-dimensional map were overlaid on the earth, with the natural resources “beneath” rather than part of them. The opening section of the film continues this through the “voice of god” narration that describes the “barren waste,” accompanied by images of barefooted locals wearing few or tattered clothes. They are shown holding buckets or jugs, implying drought conditions, reinforced by a searing sun in the sky and the predominant red and orange ocher earth tones (figure 6, Full Circle atavistic landscape). This is starkly contrasted with the oil extraction infrastructure that is subsequently shown in this landscape, with its linear architectural profile and clean, cool metal gray color (figure 7, Full Circle extraction infrastructure). The film then gives an account of the exploration, drilling, and refinery processes.

Full Circle does not provide the same level of factual and scientific rigor seen in other BP/AIOC films of this period, which present a much drier educational exposition more closely indebted to specialist disciplinary methods of graphically documenting their expert knowledge. For example, Down a Long Way, made by Halas and Batchelor in 1950, includes cross-section diagrams to depict the stratigraphic layers that create the conditions for oil formation and pooling, and that allow geologists to identify suitable drilling locations. Similarly, Chemistry of Oil, made by Larkins in 1955, is largely composed of molecular models of different carbon chains, with three-dimensional highlighting and shading to replicate the ball-and-stick models commonly used in chemistry. While Full Circle eschews a strict adherence to such diagrammatic forms, it nevertheless shows a cross-sectional representation of the drilling process reaching down to locate and extract the oil. The use of drawing and animation as an analogy are again utilized here; as the voice describes the process, “the searching pencil of the drill moves down through layer after layer to reach the reservoir,” the linguistic evocation is matched by the visual representation of the drill as a single line reaching down through layers of darkness. Once extracted and piped, the oil in Full Circle is then shown flowing through a detailed refinery complex that the Larkins animators would have some familiarity with from their earlier work on Distillation of Oil for AIOC in 1950, even if the newer example lacks explanatory labels, weakening the educational value for a lay audience.

While this tradition of intermedial diagrammatic animation is used to depict the extractive processes of oil production, the actual oil in Full Circle is not presented in scientific terms but is described as a “genie of infinite power, alive with elemental energy, dangerous, given to the spectacular.” (The suppressed cultural allusions in the film’s modernist and orientalist aesthetic are addressed in later sections of this article.) The film departs from its primarily hand-drawn two-dimensional animation to represent this, offering a highly unusual experimental synesthetic light play to capture the ineffable potential of oil it wishes to convey (figure 8, Full Circle synesthetic light play). Here the capacity of experimental animation techniques affords a distinctive method to represent the power and vitality of oil in a way that would be difficult, if not impossible, with conventional documentary techniques.

Both Andreas Malm and Stephanie LeMenager have identified the cultural imagination of the liveliness of fossil fuels and the way these seemingly inert and lackluster substances have taken on vital, or indeed animated, qualities. Andreas Malm, writing on coal and the steam power derived from it in the nineteenth century, describes how “the combustion of fossil fuels is material necromancy: the conjuring up of dead organisms, reawakening their vital forces to steer the actions of the living” (Malm 2016, 209). Likewise, in her aptly titled book Living Oil, Stephanie LeMenager explores the contradictory idea of the vitality of that fossil fuel. “Oil challenges liveness from another ontological perspective, as a substance that was, once, live matter and that acts with a force suggestive of a form of life” (LeMenager 2014, 5). The capacity of animation to represent, reinforce, and even construct this vitality of fossil fuels is central to its extensive use by petroleum and petrochemical industries, just as much as the expert traditions of diagrammatic graphic representation, with Full Circle combining the two methods in a characteristic manner. The implication of this is twofold—that oil holds great energy and potential, but equally needs scientific and management expertise over extraction and the proceeds from it.

The latter half of the film repeats this opposition between two contrasting scenarios, in its account of how the proceeds from that extraction might be dispersed in the regions where oil is located. The first part resurrects the “genie” analogy, in this case as the embodiment of the wealth generated by oil extraction and exploitation. As in the earlier sequence, the film departs from hand-drawn cartographic animation to utilize stop-motion object animation, manipulating glittering sand to create an enticing and magical vision of the transformative power of oil money, which can deliver “luxury … gaiety … a tinsel world,” as the voice-over puts it (figure 9, Full Circle genie). A bejeweled genie figure leaps around the screen conjuring cars, palaces, and champagne bottles. This is clearly intended as a cautionary tale, as the voice-over asks, “will his new masters allow him to spend his energy like oil slipping uselessly through the sand?” However, the dazzling appeal of the sequence seems at odds with the warning message, and there is a degree of hypocrisy in an oil company criticizing the coveting of motorcars.

The answering sequence returns to a rigidly rectilinear graphic representation, opening with a pair of calipers on a grid, from which new lines emerge; the camera pulls back to reveal an architect’s drawing board with a blueprint on it (figure 10, Full Circle architect’s drawing board). Any viewer with even a passing familiarity with the animation process would see a clear parallel between the tools with which animators and architects create their drawings, and the implied analogy as both are using the drawing of a line as a way to map out an as yet unrealized future. A sequence of different blueprints is shown, as if flipped through in a pile like the individual drawings of an animated sequence. These include a map of a harbor with new buildings appearing and an arch bridge extending across a river, following which fully realized constructions are seen being built in the landscape by golden coins (reiterating the circle metaphor) rolling into place to form major infrastructure such as a dam. Blueprints are maps of an imagined future, and animators, no less than planners and architects, use drawing as a way to visualize and bring into existence a vision of the world—in this case, at the service of the extractive petroleum industry.

The production of Full Circle and AIOC’s cartographic imagination of Iran

As a finished film, Full Circle offers a nonspecific universalizing message about oil extraction and its proceeds, aided by the abstracted aesthetics of animation. However, its production process was, on the contrary, deeply embedded in the specific historical circumstances of Iranian oil politics at the time, and shadows of this remain within the finished film. Full Circle was first shown in 1953, following an extended production process initiated by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1951. Originally intended for Iranian audiences, it underwent considerable revisions following the turbulent political changes in the country during the production period.

Oil extraction had been established in Iran from 1908, under the terms of a 1901 agreement between Mozaffar ad-Din Shah and British businessman William Knox D’Arcy (Yergin 2012, 118–33). The sixty-year concession underpinned the basis for the growth of APOC/AIOC but was always entangled with political wrangling both internally and internationally between Britain and Russia.[8] Those two countries occupied Iran beginning in 1941, during the Second World War, on the basis of its strategically important oil resources and geographical position (The Times 1941). After the military withdrawal, between 1947 and 1951 there was increased Iranian scrutiny of the operations of AIOC and negotiation of a supplemental concession agreement. Of particular importance to the present study, on March 15, 1951, the Iranian Majlis (Parliament) passed legislation to nationalize the oil industry (The Times 1951b). AIOC, and their majority shareholder the British government, rejected this move as outside of international law and argued it contravened earlier agreements between the parties (The Times 1951a). Nevertheless, the situation escalated politically over the next six months, with all British workers leaving the crucial Abadan refinery and other facilities by October 1951 (The Times 1951c). In August 1953, a coup supported by the US and British governments resulted in Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh being ousted in favor of Mohammad Reza Shah (The Times 1953).[9] That established conditions in which an agreement could be reached, albeit one that favored American policy over the commercial objectives of AIOC (Bamberg 1994, 488–89). Full Circle was produced and released during this tumultuous period, and as a result, it had to negotiate fraught questions about the national, colonial, and corporate control of oil production and proceeds.

Full Circle can be considered as a transitional film in the BP/AIOC catalogue, coming between the colonial image of ordered management of oil extraction and refinery in Persian Story (1952) examined by Damluji, and the need for expansion and risky prospecting for new oil sources in The New Explorers (1955) and other films addressed by Brian Jacobson (Damluji 2013; Jacobson 2021). Persian Story was filmed prior to nationalization; its production was halted prematurely due to the events in the early months of 1951, overlapping with the start of production of Full Circle. As Damluji recounts, by the time Persian Story was edited and released, it held the “exceptional status as a surviving portrait of the Westernized Iranian oil city that was lost to the British company,” a time capsule of a past world (Damluji 2013, 84). Following the nationalization crisis, “BP implemented a policy of diversification. Never again could it risk such a limited portfolio—its world had to be larger,” with Jacobson showing how the exploration films of the later 1950s documented and fulfilled this in cinematic terms (Jacobson 2021, 281). However, both authors also signal an overriding and continuing use of cinema as part of the worlding undertaken by BP/AIOC, that “foreign oil companies adopted filmmaking technologies in order to control a cultural project that linked notions of modernity and national development to the prospering oil industry” (Damluji 2013, 79) and that “film became more than just an add-on to the corporate project; it became part and parcel of oil’s world-defining work” (Jacobson 2021, 292). Full Circle sits at the pivot of these surrounding films in its negotiation between past, present, and future; the tension between the geographical specificity of Iran and universal ideals; and its continued promulgation of a message of oil-driven development. These were, however, offered in unique ways due to its production in the liminal period between 1951 and 1953 and its use of animation as a distinct form of filmmaking practice.

Full Circle’s production records and finished result serve as a unique record of a shift in the political relationship between AIOC and Iran, as well as the rhetoric adopted in later such relationships between the oil company and other nations. Animation did not simply serve as an expression of the company policy but also became a tool by which its public position was negotiated and developed. During initial discussions in February 1951, Full Circle was originally referred to as simply “cartoon film for Persia” (BP/183126 Memorandum from Seddon to Gass 23 February 1951), and the early production title of the film was “East Meets West” (BP/183126 Draft contract between Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. and W.M. Larkins & Co. 1 June 1951). While establishing the fundamental concern with place and mapping of the project, the more linear trajectory implied by “East Meets West” is indicative of AIOC’s attitude toward the topic in early 1951, lacking even the lip service to reciprocity that would develop. Original draft ideas for the film in early 1951 offered a one-sided and condescending account of “British perseverance and British money” that had initiated extraction in Persia in the early twentieth century in the face of local indifference (BP/183126 Draft A by Tritton/Keating 9 February 1951). In a highly defensive tone against the idea that it had “stolen” from Iran, the draft argued that AIOC had invested in “housing, clubs, schools, hospitals,” while implying local mismanagement and corruption of the Iranian proceeds as “it may be justly said that this money has not been wisely used, but that is not the Company’s fault” (BP/183126 Draft A by Tritton/Keating 9 February 1951). These initial plans were developed with the full involvement of senior figures in AIOC, including Norman Seddon, AIOC’s chief representative in Tehran at the time (Bamberg 1994, 607), and managing director Neville Gass (Bamberg 1994, 599), suggesting they reflected the company position. This included special approval for the £16,000 budget that was beyond the normal operational capacity of the Films Section (BP/183126 Letter to Gass 25 January 1951).[10] While there was already some awareness that the tone of such comments would be too inflammatory and controversial for a finished film, political events after March 15 overtook the production, forcing a change in approach and intended audience.

The official company history of British Petroleum and Daniel Yergin’s history of oil both give extensive detail on the political negotiations that occurred at this time, with the British government and military assuming responsibility for what was seen as “a strategic commodity which was of great importance to the defence of the realm” (Bamberg 1994, 410–58, 519; see also Yergin 2012, 432–52). As corporate histories, they are silent on the role of film within the company at this time, but the correspondence file for the film held at the BP Archive provides further insight. On 30 April 1951 Ronald Tritton, the PR director who commissioned Full Circle for AIOC, wrote to Geoffrey Sumner, joint managing director at Larkins, saying, “I don’t know how the weekend’s events in Persia will affect the film,” reacting to the appointment of nationalist leader Mohammad Mossadegh as Iran’s prime minister (BP/183126 Letter to Sumner from Tritton 30 April 1951; The Sunday Times 1951). By 9 May Tritton suggested a rapprochement in the company’s attitude to be reflected in the film, that “perhaps the ‘partnership’ idea should be emphasised rather more strongly” (BP/183126 Letter to Sumner from Tritton 9 May 1951). By the autumn of 1951, there was a clear recognition that the “original purpose … to point out to Persians the error of their ways” was no longer viable and that the film was instead to have more universal applicability in areas like the Caribbean and Venezuela, coinciding with a change in working title to The Cycle (BP/183126 Memorandum from Tritton to Chisholm 22 November 1951; Letter to Sumner from Tritton 22 August 1951). The finished film thus reflects several shifts. Firstly, it moved away from the real-world geopolitics of petroleum extraction in Iran to a more universal model that animation was well suited to. Likewise, there was a shift in tone from an unbending colonial rule and exploitation toward a businesslike model of negotiated mutual interest: from propaganda to persuasion.

Petromodernist style

The use of animation as a medium also became bound up with the wider questions the film would tackle. The immediate influence on the use of animation for Full Circle was the film Enterprise (1951), directed by Peter Sachs for the petroleum-adjacent ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries), which AIOC managing director Neville Gass had seen and admired (BP/183126 Letter to Gass 25 January 1951). Part of the fascination of Larkins’s work for ICI was the progressive modernist design Sachs and his team innovated, and Full Circle would furnish a further outlet for this. However, the increasing risk and difficulty of filming on location in Iran may also have contributed to the attraction of production in the confines of an animation studio. The apparent simplicity of the austere modernist animation style belied the resource- and labor-intensive experimentation that produced it, just as AIOC’s scientific management of oil extraction suppressed the environmental and political disruption it entailed in Iran. The application of that modernist style with the aim of quelling discontent in Iran would bring the animation studio into conflict with the commissioning company.

In a letter early in the production, Robert Tritton cautioned Larkins’s manager Geoffrey Sumner that it is “important that the style both of picture and music is not too avant-garde” (BP/183126 Letter to Sumner from Tritton 11 June 1951). As was discussed earlier, some of the most unusual and effective sequences in Full Circle are those that utilize experimental animation processes to capture the vital appeal and power of oil. In July 1952 Geoffrey Sumner reported to Robert Tritton that production of these “is giving a little trouble and this will possibly delay things slightly” (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Sumner 8 July 1952). Tritton’s response was robust, admonishing that “the money you have spent in these experiments has been in fact our money. We have been placed in the position of subsidising experimental film work … which has seemingly failed” (BP/183126 Letter to Sumner from Tritton 22 August 1952). The same desire for absolute control and ownership over oil in Iran that is documented in Full Circle had a parallel in the production relationship between commissioning company and studio, including AIOC’s disdain at the way money was spent. W.M. Larkins’s dependence on the income from this relationship necessarily required them to acquiesce, and Sumner promptly responded with a conciliatory letter to assuage Tritton’s concerns and assure him that the film would be delivered as contracted and within budget (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Sumner 26 August 1952).

It is also notable that Peter Sachs corresponded with Tritton at the end of the production process, seemingly an unusual circumstance as Sumner had managed the day-to-day production throughout the two-year process. Sachs’s letter suggested that he had “enjoyed making Full Circle perhaps more than any other film” and expressed satisfaction at bringing modernist aesthetics to a mass audience, that “50 years ago only a handful of people were able to get pleasure out of looking at an impressionist painting. It is most encouraging to know that many people can enjoy looking at Full Circle. That some don’t like it is right and understandable” (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Sachs 7 July 1953). However, he also compared himself to a court portraitist, obliged to “paint my patron’s likeness in all his finery … with a halo above his head … for all the world to see that he was a good man” (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Sachs 7 July 1953). Sachs’s need to maintain the favor of a sponsor is evident, even while he discloses the creative oversight and control incurred in the transaction, revealing both the costs and the benefits of useful animation production for studios like Larkins.

It is important to recognize that, like the material and economic extraction that AIOC undertook that motivated Full Circle, the modernist aesthetic approaches utilized in the film were also rooted in an extractive logic through its primitivism. As a long historiography of art has detailed, Cubism, Futurism, and other modern art movements were embedded in a form of primitivism that the artists and early commentators saw as celebrating non-Western artworks but that also problematically appropriated them for their own purposes. Early art historical accounts of this primitivism, which would be those current at the time of the production of Full Circle and other films addressed here, offered an uncritical celebration and exploration of the different inspirations for modernist art, such as Robert Goldwater’s influential book (Goldwater 1938, 1967). Later writing in the 1980s following the 1984 New York Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and Modern voiced more critical dissent, with Lucy Lippard accusing the work of being “pillaged from other cultures” (Lippard 1990, 24) and others offering similar challenges (McEvilley 1984; Knapp 1986). Some nuance is evident even in such trenchant correctives—for example, James Clifford found the art guilty of “appropriation of tribal productions” even while it was “not simply imperialist” as it provided “strong critiques of colonialist, evolutionist assumptions” (Clifford 1988, 197). Later writers have likewise looked to develop a nuanced account that goes beyond denunciation to understand the complex and contradictory implications of the primitivist impulses of modernism (Connelly 1995; Errington 1998).

In light of these accounts of the primitivist modernist art that in turn influenced the films discussed here, Full Circle is problematic in that it follows the earlier avant-garde art in appropriating aesthetic elements with little sense of context or specificity. Just as oil was removed from its geographical context and transformed for the purposes of distant corporations and governments, so aesthetic practices were separated from their culturally specific contexts and put to new use. The Cubism that director Sachs so admired is used in the film to depict the “barren” land the film starts with, easily read as a desert—primitivist art used to depict a “primitive” place. The irregular angled rocks and land formations of the desert setting, combined with complex shading, produce an effect comparable to, for example, Pablo Picasso’s Three Women (1907–8, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) (figure 11, Full Circle Cubist style). In contrast, oil is later shown flowing beneath a lush jungle-like setting depicted in the style of Henri Rousseau, whose work offered a distinctive type of primitivism centered on his “naive” and “untutored” approach to painting (figure 12, Full Circle jungle). The various forms of transportation linked by circles, discussed earlier, evokes Futurist work, such as the painting of Tullio Crali. At a remove from the original indigenous sources that influenced modernist artists, Full Circle utilizes nonspecific modernist primitivism that flattens distinctions between different cultures, constructing a homogeneous “other.” While the source art was most often influenced by African art, here it is used to represent a generic Middle East milieu. A similar tension is seen in other BP/AIOC-sponsored films, which not only incorporate similar primitivist modernist aesthetics but also use them to depict caricatured representations of indigenous peoples in oil-producing regions, seen in The Power to Fly or Down a Long Way.

Full Circle was initially planned as specifically about AIOC’s relationship with Iran; the political situation described above resulted in a shift away from representing a particular country, contributing to the ill-defined sense of place and the style used to depict it. One production note from Robert Tritton to the Larkins studio asked, “The women. Can they be exchanged for something less ‘middle eastern.’ Our point here is to remove the film from a purely Arabian or Persian context” (BP/183126 Letter to Sumner from Tritton 16 October 1952). Yet traces of the geographical and political specificity of AIOC’s ties with Iran remain in the finished film, most notably in the orientalist allusions to “genies” in depicting the power and vitality of oil and the wealth it generates. While the film wants to persuade the audience of a clean and efficient petromodernity abstracted from geographical and cultural specificity, it cannot resist the appeal of the luxurious “tinsel world” nor fully conceal the exoticism that underpins it. In responding to the particular circumstances of the nationalization of oil in Iran, and in an attempt to rethink the power relations inherent in extractive processes, Full Circle retreated to universalizing principles to forward BP/AIOC’s interests. In doing so, it became increasingly clumsy and incoherent. Despite its aesthetic charms and experimentation, it is implicated in an inequitable set of power relations inherent in the extractive logic of both the oil industry and primitivist modernism. Yet its aesthetic and political disorder is a revealing reflection of the historical context from which it arose, and therefore all the more valuable for study.

Surveying Full Circle

After the completion of an initial rough cut of Full Circle, and reflecting the highly unusual circumstances in which it had been produced, AIOC conducted an unprecedented survey of employees, senior management, and government officials who were shown the film and asked to give their opinion on it. An initial screening of the film for Sir William Fraser (chairman), Neville Gass (managing director), and Basil Jackson (deputy chairman) indicated a mixed response, perhaps influenced by the “advanced idiom” of the modernist style as well as the mixed political message (BP/183126 Letter to Chisholm from Tritton 8 May 1953). At their suggestion, Tritton issued invitations to a test screening on 11 May 1953 to a wide audience whose responses reflected the diversity and unsettled viewpoints about the company’s future and how to respond to the ongoing situation in Iran. Such a commitment of time and resources, and involvement of the most high-ranking personnel, indicates the importance given to film production within the company in this period. The screening and survey went beyond verifying corporate communications to also provoke self-reflection on company policy and strategy. This animated film became a factor in high-level decision-making. The survey responses also revealed differing understandings of the purpose of the company’s filmmaking endeavors, which align with the intersecting fields of this article: animated documentary, useful animation, and petroculture.[11]

The Training Division focused on the disparity between the relatively factual diagrams (“suitable for a more technical and more intelligent audience”) contrasted with the genie sequences (“more suitable for a simple audience of low I.Q.”) (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Training Division 12 May 1953). Similarly, the Geological Department offered a critique of the sensational representation of oil that they saw as more akin to lava and therefore lacking factual accuracy (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Pedder 12 May 1953). These departmental experts judged the film as a form of animated documentary, assessing its scientific veracity and pedagogical value.

Senior figures offered a more politically informed but no less mixed viewpoint. Norman Seddon had contributed to the original ideas for the film in early 1951 when he was AIOC’s chief representative in Tehran, and he was one of the AIOC employees subsequently evacuated, becoming general manager in the Distribution Department in London (Bamberg 1994, 607). He praised the film as “first class—striking, original”; however, he felt the message of the film was incoherent, neither appealing and persuasive enough to be effective to change the views of an Iranian audience yet lacking sufficient explanation to be of educational value to Western audiences (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Seddon 12 May 1953). James Addison, a lawyer who had participated in negotiations between AIOC and the Iranian government, likewise found the film ambiguous: “was the film meant to indicate that these things—i.e. the bridges, dams etc.—ought to happen, do happen, will happen or might happen if someone did something differently? Who is the someone who influences whether they do or don’t or will or won’t happen?” (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Addison 12 May 1953). Company executives judged the film as a form of useful animation, evaluating it in terms of its operational value and persuasion of varied audiences.

Government figures were also consulted, and they evaluated the film and the values it put forward, indicating the extent to which the company remained beholden to the state, both as majority shareholder and major customer. Sir Robert Fraser was director general of the Central Office of Information and soon to play a key role in the development of commercial television in Britain, and therefore in the vast expansion of the use of the moving image for advertising and PR purposes. Fraser offered a largely flattering account of the film but implied it would not be well received by those Iranian audiences who were “incorrigibly inflamed against the West on economic grounds,” despite the film being, in his view, “perfectly accurate representations of the low and primitive standard of life in the oil territories” (BP/183126 Letter to Tritton from Fraser 9 June 1953). Political representatives understood the film as a form of petroculture, gauging its potential role in international relations and energy security.

The full range of responses recorded in the BP Archive suggest that Full Circle was a representative record of AIOC’s and the government’s position on their relationship with Iran as of May 1953, which is to say highly uncertain and disjointed. The film recognized the necessity of concessions and greater reciprocity than had previously been allowed, but likewise was highly speculative about what the future relationship with Iran (or other oil-rich countries) might look like, and wary of the potential power that might be unleashed in the process. These internal debates were also captured in the aesthetics of the finished film, which contrasted experimental animation techniques to produce affective responses to the promise of oil and the wealth it could bring, in opposition to the ordered diagrammatic representation of the scientific management of oil extraction. The film is couched in universal terms but retains buried traces of this historical moment.

Conclusion

The BP/AIOC animated films addressed here used animation to visualize the past and future of oil extraction. Studying the entwined history of the animation and oil industries can likewise help us to understand the role of media in our dependence on fossil fuels and the futures this may result in. Exploring that history is itself a process of scholarly extraction, digging deep into archives to locate rich seams of untapped resources. Imre Szeman and Jennifer Wenzel rightly warn of the danger of “conceptual creep” in the metaphorical usage of extractivist language, which may weaken the value of attending to this topic or make overcharged claims for the importance and effect of humanities research (Szeman and Wenzel 2021, 511). Heeding this call for caution against “dematerialisation,” we might still recognize the deeply material nature of the history presented here, shaped by the physical archival practices around it. The paper-based BP Archive is a rich resource that has been largely ignored by film and media scholars beyond those cited here. However, its existence is shaped by its continuing association with present-day oil extraction interests—for example, in an embargo on access to materials dating from after 1955 (Shafiee 2018a; Damluji 2021). In parallel, prior scholarly and archival disregard for animation, especially in its sponsored form, means traces of the animation studios discussed here are scarce, and most are likely lost (Stewart 2016). Full Circle is currently accessible only on-site at BFI premises, and it is one of the few BP/AIOC animated films that does not feature within the online BP Video Library, although it is unclear why. Online video repositories and digitized newspaper archives have enabled the location of scarce sources for this study; however, we must be mindful of the energy regimes these are still bound to (Marks et al. 2020). This article has argued for the importance of the historical material entanglement of the animation industry with extraction industries, but we must also be alert to the present-day materiality of archival sources and the ways these shape our understanding of that history.

Full Circle and many of the other BP/AIOC-sponsored films raised here use animation to look to the future and speculate about what it might hold. As might be expected of films sponsored by a petroleum company at a time when ecological awareness was only slowly emerging, they do not directly speak to our present-day concerns with the environmental impact and destruction resulting from fossil fuel usage. As Patrick Russell, Brian Jacobson, and others have explored, BP would start to acknowledge environmental concerns in the following decades, most famously in Shadow of Progress (1970), made for the first European Conservation Year (Russell 2010; Jacobson 2019). This acknowledgment also included animated examples like Children and Cars (1970), made for BP by Halas and Batchelor, which echoes their independently produced and more overtly ecocritical Automania 2000 (1963). Yet, even in the animated BP films that preceded the burgeoning environmental movements of the 1960s and 1970s, a contemporary viewer cannot help but see the seeds of what was, and is yet, to come. The warning of the danger of unleashing the genie of oil in Full Circle or the reminder of the formation of oil from death and decay alongside the extinction of dinosaurs in As Old as the Hills serve as inadvertent harbingers of the future that was being wrought by the growth in oil production and usage. Studying these films can serve to highlight the continued and growing urgency of considering their implications for our own futures.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Alireza Fakhrkonandeh, Brian Jacobson, and Colin Williamson, as well as the editors and peer reviewers of this journal special stream, who gave insightful feedback and discussion that has greatly improved this article. I would also like to express thanks to the staff of the BP Archive at the University of Warwick, BFI National Archive, BFI Special Collections, and the BFI Library for their tireless and knowledgeable assistance during the research and writing of this article.

Archival Sources

BP Archive, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick, UK

BFI/HAB Halas & Batchelor Collection, British Film Institute Special Collections Berkhamsted, UK

The company was known as the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) prior to 1935, when it was renamed the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) to reflect the endonym used within the country, although the exonym Persia remained in common usage in company correspondence and British press. Following the 1950s oil nationalization crisis (described below) and the company’s reduced role in the region, it was renamed the British Petroleum Company in 1954, legally adopting a name already used for consumer branding and advertising (Bamberg 1994, 552–53).

There is a growing library of humanities research that sits alongside scientific and social-scientific understanding of the causes and effects of anthropogenic change to our natural environment. In relation to petroleum, the collections Oil Culture (Barrett and Worden 2014) and Petrocultures (Wilson, Carlson, and Szeman 2017) have been especially influential.

In parallel with the growth in environmental humanities, film studies has seen increased attention to what are variously called “films that work” (Hediger and Vonderau 2009), “useful cinema” (Acland and Wasson 2011), “sponsored film” (Prelinger 2006), or “non-theatrical film” (Slide 1992). The Petrocinema collection, and further work by its contributors, have fruitfully brought petroculture and useful cinema studies together.

While much of the interest in animated documentary has been around contemporary examples that provide evocative and affective representation of the unseen or unseeable, such as mental states and memories, authors including Annabelle Honess Roe, Cristina Formenti, and Mihaela Mihailova have contributed valuable insight into the types of factual and instructional historical work that is the focus here (Honess Roe 2013; Mihailova 2019; Formenti 2022), building upon earlier accounts of animated documentary (Wells 1998; Ward 2005).

Most of these films can be viewed online at https://www.bpvideolibrary.com/.

Certificates for festival entries are included in many of the files in the Halas and Batchelor Special Collection held by the BFI—see BFI/HAB-1-22-4, BFI/HAB-1-32-2, BFI/HAB-1-42-2, BFI/HAB-1-45-1/2, BFI/HAB-1-46-3.

For further exploration of these issues in relation to animated maps, see Fidotta 2014.

Malm and Esmailian provide a chronology of key events and broader context for the political history of Iran (Malm and Esmailian 2007). Bamberg’s official company history of BP provides a corporate perspective on these events (Bamberg 1994), while Shafiee provides a sociotechnical perspective (Shafiee 2018b).

There is considerable variation in the transliteration of Farsi names to English in the sources cited. For consistency here, the most common spelling used in the International Journal of Middle East Studies has been adopted, except when directly quoted from historical sources.

The comparable film As Old as the Hills (1950) had an initial budget of £5000 (BP/183094 Invoice from Halas and Batchelor to AIOC 6 July 1949), the same price as quoted for We’ve Come a Long Way (1952) (BP/183149 Halas and Batchelor budget 16 February 1951)

While John Halas did use the term “animated documentary” in other times and contexts (Formenti 2022, 54–55), it is never used within the production materials for the films discussed in detail here, suggesting that these animated petroleum films were understood as a distinctive form of filmmaking. The contemporary terms “animated documentary,” “useful animation,” and “petroculture” are retroactively applied here to clarify the historical perspectives.