Introduction

This article explores the intersections between industrial agriculture, mass media, and extraction. Examining color photographs and films produced by the oil and chemicals corporation Royal Dutch Shell, I show how visual media helped to normalize the use of petroleum-derived pesticides in Britain in the years after the Second World War. I was initially drawn to this subject after viewing a series of films released by Shell in 1950 under the title Plant Pests and Diseases, held at the British Film Institute (BFI) archive in London. The films were directed by J. V. Durden, a British filmmaker whose career originated in the popular natural history film genre and who later specialized in technical and instructional films. I was intrigued by the ease with which Durden’s skills in scientific—and especially entomological—filmmaking were repurposed to sell pesticides in the 1950s. The release of these films corresponded with the rise of Shell’s new petroleum-derived pesticides, pointing to the interconnected histories of fossil fuel extraction, agricultural production, and visual media. Films and photographs created by the Shell Photographic Unit and the Shell Film Unit “naturalized” the company’s marketing of pesticide products, helping farmers to visualize their insect and fungi “enemies” while eliding or obscuring the long-term environmental and social risks that these chemicals posed. The material basis of these brightly colored films and photographs was itself entangled with the chemical revolution as they entered a global distribution market that was a product of the twentieth century’s fossil fuel culture. These images help us to make sense of the threads linking industrial agriculture, extraction, and corporate sponsorship precisely at the time when petroleum and its chemical by-products were changing the world beyond recognition.

As Adam Romero has demonstrated, agriculture underwent a “petrochemical turn” between the 1920s and the 1940s, following the discovery of new chemicals derived from petroleum, including both pesticides and fertilizers (Romero 2016). Royal Dutch Shell Group (henceforth “Shell”) launched into the chemicals industry in 1929 under the banner of Shell Chemicals, and began releasing a wide range of pesticides into the UK market in the years after the Second World War. That pesticides were as indiscriminate as they were lethal was evident very early on to research scientists, ecologists, and environmentalists. As John Sheail and others have argued, concerns about the impacts of pesticides on both people and the environment were raised long before the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), which transformed the issue into a mass media phenomenon (Sheail 2013; Clark 2017). The zoologist Solly Zuckerman, for instance, chaired three Ministry of Agriculture working parties in the 1950s leading to limited state regulation of the application of pesticides, including the Agriculture (Poisonous Substances) Act of 1952, which introduced mandatory protective clothing for workers handling chemicals. Meanwhile, environmental interest organizations, alongside groups representing game shooting like the British Field Sports Society, raised the alarm over the sudden decline in the population of wild birds, which spiked in the late 1950s and early 1960s due to the deadly pesticide coats applied to seed mixes (Sheail 2013). Given the relatively brief window between the arrival of modern petrochemical pesticides and the growing public awareness of their catastrophic impacts on the environment, the period immediately after the Second World War is particularly important for understanding how the use of chemicals was normalized as a central component of modern farming. As this article shows, lavish and highly detailed color photographs and films, deployed across a range of mass media settings, were critical to this effort, portraying insect “pests” as a pressing problem to which chemicals presented the only apparent answer.

As Sabine Clarke and Thomas Lean have shown, the uptake of pesticides by UK farms in the years after 1945 was neither immediate nor automatic. Moreover, pesticide use varied widely: while growers of high-value crops like hops and fruit had sprayed their orchards and fields with chemicals for decades, arable farmers took up pesticides much more gradually in the postwar years (S. Clarke and Lean 2022). To convince farmers to invest in pesticides, both businesses and government bodies set out to get farmers to “visualise the insect pests on their land” (S. Clarke and Lean 2022, 38). Number crunching, as Clarke and Lean have demonstrated, was one way to do this: presenting the scale of their losses to these “pests’” in stark financial terms, often through detailed surveys and modeling, created a new problem for farmers which had previously been difficult to quantify or visualize. The definition of what counted as a “pest,” then, was by no means fixed in the eyes and minds of many farmers in the 1940s: “pests” had to be constructed as a category and as a threat before they could be eradicated. Where Clarke and Lean focus on financial visualization, my concern here is instead with images. By building a collection of detailed, full-color photographs and films of insects and plant diseases, Shell aimed to assemble what they believed to be a dossier of visual proof of the need for chemical pesticides.

In this article, I limit myself to Shell’s public relations and research activities roughly between the 1940s and the early 1960s, while reflecting more broadly on the relationship between visual culture and extractive capitalism in the twentieth century and beyond. This was a period marked by postwar technological optimism and growing interconnectedness, with international organizations like the United Nations turning to science and technology as a potential solution for global problems such as world hunger or the eradication of malaria (Muschik 2022). As the international order was reshaped in the wake of decolonization, food security and rural development came to play a fundamental role in the relationship between colonial metropoles and their former colonies. Multinational corporations like Shell, with their formidable command over the flow of both resources and information, positioned themselves at the center of this new developmentalist discourse, auguring a new phase in the history of extractive capitalism.

Pesticide research and the oil industry

In the years following the Second World War, Shell advertising often claimed that the company’s investment in the petrochemicals industry was helping to address a wide range of modern problems. A full-page advertisement from 1954 under the heading “Oil means brainwork” (figure 1) listed some of these: Shell was fighting malaria, producing weed killers, and developing plastics, synthetic textiles, and detergents. “Petroleum chemicals,” the ad announced, “are helping to feed the poor and clothe the world, and to cure its sick.” This language echoes the tone of much of the writing about pesticides between the 1940s and the 1960s: petroleum had helped to win the war, and now it would help to win the peace. The oil industry elided the toxic and potentially harmful nature of petrochemicals on human and environmental health, instead using their sizable advertising and marketing budgets to paint a picture of petroleum research as being fundamentally clean and ethically robust.

Agriculture was closely integrated with the revolution in oil production and consumption in the twentieth century: tractors and other machinery guzzled increasing amounts of petrol, while the soil itself and the plants that grew on it were dusted, sprayed, and fertilized with chemicals that derived from the oil industry’s waste products (Romero 2016). Although certain chemicals such as pyrethrin, copper, and sulfur were used as pesticides in the nineteenth century and earlier, it was only in the twentieth century that more complex chemicals began to appear (E. P. Russell 2001, 5–6; Davies et al. 2007; Brassley 1995, 68). The refining process of crude oil produced several waste products, including various gases, and advances in the process of cracking (essentially breaking down large compounds into smaller units) enabled a greater proportion of gasoline to be produced per barrel of crude oil (Romero 2016; Larraz 2021; Carswell 1952). Researchers found that hydrocarbons could be broken down into extremely malleable substances such as ethylene, propylene, and butylene, in turn used to synthesize chemicals that became key ingredients in a dizzying array of new industrial and consumer products, chiefly plastics, detergents, cosmetics, and pesticides.

The growing reliance on chemical pesticides in the twentieth century was closely correlated to the history of military conflict. As Edmund P. Russell has shown, entomologists and chemical researchers worked alongside military institutions, and knowledge about the effects of certain compounds on animals influenced the development of equally lethal chemical weapons targeted at human beings (E. P. Russell 1996, 2001). For instance, hydrogen cyanide was deployed by France at the Battle of the Somme, while US scientists repurposed arsenic supplies originally intended for farming to develop poison gas during the First World War (E. P. Russell 1996, 1511). The use of dehumanizing language comparing enemy soldiers and civilian populations to insects and vermin, moreover, normalized the logic of annihilation and extermination for which these powerful new chemicals were explicitly designed. The use of chemicals in combat during the Second World War was more limited, but close affiliations between industry and chemical businesses saw new chemicals being tested to fight insect infestations as well as controlling health hazards such as malaria. The German Nazi regime demonstrated the unfathomable scale of horror that modern industrial chemistry could inflict on human life during the Holocaust. Between 1942 and 1945, SS officers at Auschwitz used Zyklon B, a chemical manufactured by I. G. Farben, to murder more than a million people in the death camp’s gas chambers. That the canisters of Zyklon B used at Auschwitz were labeled with the word “pesticide” is a potent reminder that the only true unifying characteristic of this class of chemicals is their lethal toxicity. Pesticide manufacturers, particularly in the postwar years, may have wished to portray their chemicals as harbingers of life, peace, and prosperity, but their devastating potential to systematically kill remained unchanged.

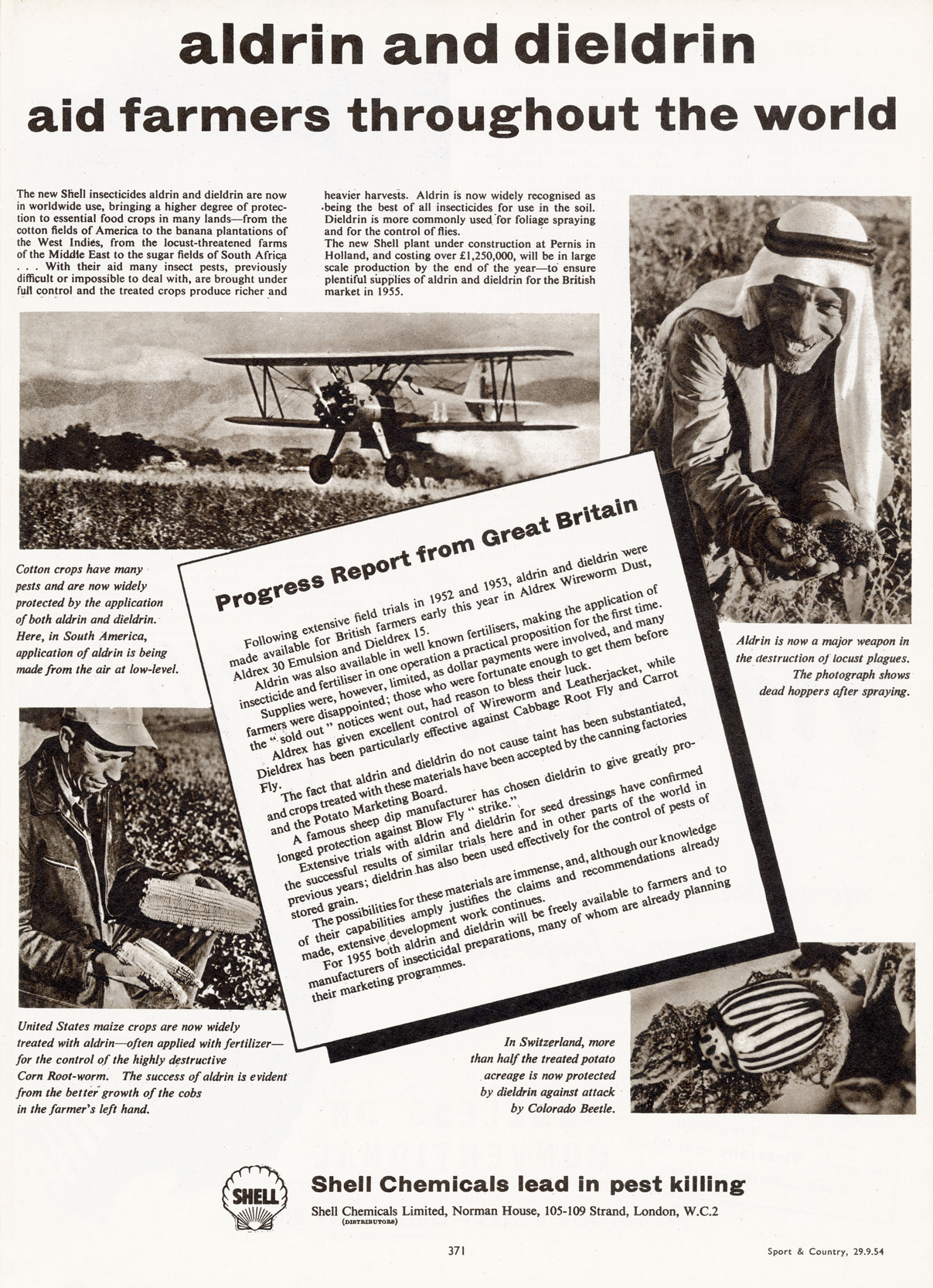

Shell began investing intensively in petrochemical research in the 1920s, with researchers based principally in Amsterdam and California. Shell’s experiments with petrochemicals intensified during the Second World War, and by 1945 Shell had become a major player in the production of petrochemicals for agriculture (Howarth and Jonker 2007, 10–103; Romero 2016). Two new pesticides would become crucial to the corporation’s product list: Aldrin and Dieldrin. Both were organochloride pesticides—that is, pest control products composed of chlorinated hydrocarbons. Aldrin and Dieldrin were synthesized by combining two hydrocarbons obtained from oil refining, hexachlorocyclopentadiene and bicycloheptadiene. Aldrin and Dieldrin were not the only pesticides derived directly from oil. Both DDT and BHC (Lindane), which became popular pesticides during the war, required benzene for their production, another major oil refining by-product. In the years following the war, oil gradually became the principal source of UK energy consumption, finally surpassing coal in 1972 (Warde 2007, 69). As oil consumption increased, so, too, did the proportion of petrochemicals made from oil instead of coal, rising in the UK from 9 percent in 1949 to 63 percent in 1962 (Howarth and Jonker 2007, 334).

In 1945 Shell purchased Woodstock Farm in Sittingbourne, Kent (UK). Over the next five decades, this previously failing farm would become the heart of Shell’s agricultural research activities outside of North America (Shell 1995). The farm comprised 332 acres of land, including 30 acres of hops and orchards and 80 acres of arable land. It was managed as an ordinary commercial farm, on which Shell’s scientists tested a growing range of pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers. A similar research station had been established in 1928 at Jealott’s Hill in Berkshire by Shell’s competitor ICI, which released pesticides under its subsidiary Plant Protection Limited (Peacock 1978). These stations mirrored state-supported facilities in places like Rothamsted, Long Ashton, or East Malling, which since the late nineteenth century had been the key drivers of research into agricultural productivity in Britain. Far from being an isolated or secretive research facility, Woodstock Farm became the subject of advertising campaigns which sought to reinforce Shell’s association with advanced and sophisticated scientific research. For instance, figure 2, an advertisement published in The Times in 1952, contrasted a woodcut-style drawing of traditional sowing with a modern photograph showing a row of large beets growing in soil. Sitting between both is an illustration of a test tube with a hop-like crop growing inside. As well as emphasizing the contribution of Shell’s own “experts” in addressing “problems of importance to the nation’s food production,” perhaps the most striking aspect of the accompanying text is the image of corporate responsibility that it seeks to convey. Trials at Woodstock, readers were assured, were “carefully controlled” and part of a gradual “step-by-step progress.” Advertisements like this one grossly mischaracterized the work of scientists at Woodstock by equating investment in research with a guarantee of product safety.

If the development and growing availability of pesticides came about in the wake of the petrochemical revolution, their promotion in photographs and films was also made possible by related advances in the field of chemistry. Aniline synthetic dyes, derived from coal tar, facilitated the arrival of color photography in the late nineteenth century, and for the next half century major manufacturers like Kodak and Agfa would be key players in the global chemicals industry (Flückiger, Hielscher, and Wietlisbach 2020; Angus et al. 2022; Tucker 2022). These new material products of modern photography, moreover, could themselves be subject to infestation by nonhumans, especially earwigs and flies with “a liking for a diet of damp gelatine”—a sterile environment therefore became a prerequisite of the modern photographic studio (Anon. 1932). In the next section, I explore one such studio: that of the Shell Photographic Unit in the 1950s.

The Shell Photographic Unit and entomology

In the interwar years, Shell developed a corporate marketing and public relations strategy that made it an instantly recognizable brand. Under the direction of the public relations pioneer Jack Beddington, Shell’s corporate image flooded the British cultural landscape. Posters, pamphlets, magazines, and films, as well as eye-catching art and important events, were all bankrolled by Shell (Heller 2010; Anthony, Green, and Timmers 2021). This multimedia presence enabled the corporation to associate its brand with subjects that were not directly connected to the oil industry. The Shell County Guides, for instance, a series of regional guidebooks first launched in 1934, played an important part in shaping the public’s view of the countryside precisely at a time when the growing popularity of the motorcar was beginning to transform access to these spaces (Heathcote 2010). Indeed, by the 1940s Shell had successfully positioned itself as a brand linked to the British outdoors, something that even at this time stood in great contrast to the negative environmental consequences of mass motoring and petrol consumption (Hewitt 1992; Brown 1993; Aukland-Peck 2021). After the Second World War, Shell used its sprawling marketing operations to promote the company’s new chemical products, producing colorful pamphlets and other printed matter aimed at selling pesticide products to farm managers eager to maximize their production.

Just as important as the marketing of individual products was a broader public relations strategy that had the goal of normalizing the need for pesticides in the eyes of the British public. A magazine article (figure 3) that appeared in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News in 1950 drew a direct link between the research undertaken at Woodstock Farm and the role of visual technologies in bringing this work to the attention of the public. The article, titled “Photography versus the Pest,” explained:

The growth and complexity of this range of agricultural chemical products discovered by the scientists … raises another problem. That is the need for a visual medium enabling the grower to identify the type of pest or disease causing trouble, so that the correct counter-measures can be taken. (Anon. 1950)

The author described the work of the Shell Photographic Unit, who were working alongside scientists at Woodstock Farm to produce color images of a wide range of insects and fungi that could cause damage to crops.

Formed in 1946, the Shell Photographic Unit was a central component of Shell’s marketing and public relations operations (Knight 1960). With a state-of-the-art studio in central London, it rapidly gained a reputation for high-quality industrial photography. The unit documented the corporation’s activities all around the globe, from oil and gas refining to motoring and aviation. While most of its photographers traveled the world in search of material for Shell’s marketing and public relations departments, the “pest” images were made in the controlled environment of a laboratory. They were overseen by Clive Cadwalladr, who is pictured in several of the photographs printed in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News article. Wearing white lab coats, Cadwalladr and his team neatly embody the alliance of photography and science—or, rather, the idea of photography as science. Encoded in these photographs were two distinct messages about the role of scientific research in Shell’s agricultural activities. On the one hand, they reminded people of the practical science underpinning their development of new pesticides at Woodstock Farm. On the other, photography was depicted as a scientific process in its own right, requiring specialist techniques and equipment as well as an intimate knowledge of the insect subjects themselves.

The article went to great lengths to emphasize the equipment and techniques involved in taking and producing entomological photographs. This included a “Holophot” photomicroscope and a photomacrography layout for taking detailed “close-ups of plants and buds.” The article also highlighted some of the difficulties that were specific to photographing insects, with “specimens wilting in the heat” or insects becoming “overactive when exposed to high temperatures,” making it hard to capture them when a long exposure was required. That the unit believed they were creating new forms of observing insects through the work is captured in a note at the end of the article saying that they “will be pleased to provide any technical information gathered during this period of research and experimentation” (Anon. 1950).

Cadwalladr and his team aimed to create a repository of accurate images with an encyclopedic scope. The photographer Derrick Knight recalled that “the chemists and the salesmen of Shell Chemicals needed pictures of all the common insects of the world,” but that a suitable repository of images, covering the full life cycles of individual species, did not yet exist (Knight 1960). As historians of science have long established, new technologies of visualization have often been hailed for their presumed ability to create comprehensive and objective visual repositories of knowledge (Daston and Galison 2010). However, photography also offered advantages beyond the encyclopedic. As one British entomologist who used Shell photographs for illustration argued:

Whereas a picture of a dead insect often gives little more than a poor reminder of what one saw when it was alive, a coloured picture of the living insect may show more than could be taken in with the naked eye. (Oldroyd 1958, 187)

In a later article for Discovery magazine, moreover, Cadwalladr wrote: “Photography, especially colour photography, has become a useful aid to the entomologist and plant pathologist… Photographs may also help to instruct farmers and market gardeners” (Cadwalladr 1956, 370). The unit’s entomological images, then, blurred the lines between pedagogy and marketing.

Two of the photographs published in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News emphasized the importance of color to the unit’s photographs. On the bottom left, we see a woman making large color reproductions of a raspberry maggot photograph. On the top right, a man is pictured using the dye transfer technique to guarantee that the final color images were accurate. This was a time-consuming and technical process usually reserved for advertising and film. Nevertheless, the images in the article itself were printed in grayscale, which remained the standard for widely circulated newspapers and magazines in the early 1950s. The same was true of a similar article showcasing photographs taken by the Shell unit that was published in the Illustrated London News, also in 1950. Luxurious, glossy images in full color, which were a hallmark of oil industry marketing publications at this time, could not be matched by these more quotidian publications. Nevertheless, both papers alluded to the colorful qualities of the original photos. In the caption for a picture of the raspberry maggot, for instance, the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News noted: “This, we regret, gives little idea of the magnificence of the Shell colour picture, which is so true to nature that your hand automatically goes out to pick off the offensive maggot” (Anon. 1950). The language here reinforced the principle that the greater the resolution of the image, the more likely viewers were to appreciate the “offensive” nature of the creature in question. One magazine did print the photographs in color: in 1956 the popular science magazine Discovery published two photographs (figure 4) from the unit’s entomological collection to illustrate an article by Cadwalladr (Cadwalladr 1956). This was rare for a magazine that otherwise exclusively used grayscale when printing photographs: by making this exception, the editors underlined the special quality of these color images.

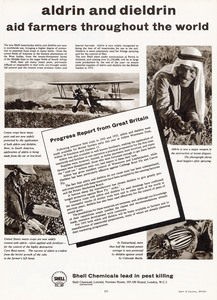

The photos taken by Cadwalladr and his team at the Shell Photographic Unit had a wide range of applications for Shell’s public relations department. They were used by Shell employees and agricultural extension workers as lantern slides in lectures, in exhibitions, and in informational pamphlets. The unit produced 35mm transparency slides for projection of the photographs, each branded with Shell’s distinctive logo. Slides like these could be projected by touring lecturers, but collections were also shared with natural history and scientific societies: the archive of the Manchester Museum, for instance, holds 443 of them (Logunov 2009). These slides permitted the lecturer to enlarge the image without loss of quality, which meant that the unit’s detailed work could be shown in all its glory. Occasionally the unit’s photos were used in advertisements, as in the Aldrin and Dieldrin ad in figure 5, which featured an image of the Colorado beetle on the bottom right. By 1966 roughly a quarter of the library’s entire catalogue of 22,500 images, which covered the full range of Shell’s business activities, were on the subject of “agricultural and horticultural pests and diseases” (McNeil 1966, 128–29). Film Centre Photographic (FCP) licensed many of these images for publication in dozens of specialist and popular books, where again they usually appeared in black-and-white reproductions of the originals. For instance, G. Fox Wilson’s Horticultural Pests: Detection and Control (1963), a technical publication for gardeners, and Harold Oldroyd’s Insects and Their World (1962, figure 6), a popular introduction to entomology, both included multiple full-page illustrations of insects sourced from Shell’s photo library (Wilson 1963; Oldroyd 1962). The photographic unit’s collection of entomological photographs represented a systematic attempt to visually document insects and plant diseases. It was an exercise in making these visible—not just to potential customers in the farming community but also to a much wider public. By seeking to establish a new photographic standard for accurately recording these “pests,” the Shell Photographic Unit created an extensive library of images that would stretch far beyond their initial use, finding their way into a diverse range of print publications over the succeeding decades.

In 1961 the unit was transferred to Film Centre International and was renamed FCP Studios (McNeil 1966, 130). Film Centre had initially been established by John Grierson as a consultancy for film production companies making documentary films, which now opened new premises on Oxford Street. With this move, Shell brought its photographic and film units under a single roof, all while externalizing the management of both to outside contractors. Previously, each unit had operated entirely independently—the only exception to this being the production of film stills by the Shell Photographic Unit for promotional publications. Nevertheless, they did share considerable overlaps, which are best exemplified in the career of Derrick Knight (1919–1994), who worked at the photographic unit between 1946 and 1960, first as chief photographer, and from 1956 as the unit’s manager (Campbell 1976). Knight had begun his career working with John Grierson in the GPO Film Unit, and he spent much of the Second World War shooting war footage for the Army Film Unit (Anon. 1994). The kind of “industrial photojournalism” pursued by Knight and other photographers at the photographic unit shared much in common with the ideals of the documentary film movement espoused by the film unit under Stuart Legg, which combined an uncompromising commitment to visual realism with a fascination for industrial processes and the people responsible for them. Pesticides were also the unspoken subjects of several films commissioned by Shell: in the next section of this article, I explore a series of color films released by the Shell Film Unit in the early 1950s.

From natural history to pesticide films

As Teresa Castro has shown in the case of “ruderal plants” (meaning “weeds” and other “fortuitous plants”), film history offers a rich territory for exploring the status of maligned, detested, or ignored nonhumans (Castro 2023). During the 1920s and 1930s, short natural history films were a frequent fixture of cinema evenings across the UK. In the eyes of many contemporaries, natural history films stood in wholesome contrast to mainstream cinema, promoting at once outdoor leisure and scientific knowledge. The most well-known of these were the Secrets of Nature series produced by British Instructional Films, and their later successors the Secrets of Life series. The filmmaker F. Percy Smith had been at the heart of the Secrets project from its earliest years. His inventive techniques of microcinematography and stop-motion were crucial to bringing insects, fungi, and other organisms into public view and established the visual style and format of the Secrets films as well as the wider natural history genre (McKernan 2004; Gaycken 2015, 54–89; Jaikumar 2019, 53–56).

Smith’s filmmaking studio, based in the London suburb of Southgate, was a hive of activity. Alongside his wife, Kate, and his assistant Phyllis Bolté, he built a series of elaborate homemade contraptions aimed at capturing a wide range of natural phenomena (Long 2023). Often this entailed a detailed knowledge of the life cycles of insects and plants: The Strangler, for instance, was a film about dodder, a parasitic plant that sucks nutrients from its victims. In making this film, Smith found it difficult to find information about how to grow dodder from the usual reputable sources. Botanical gardens, horticultural journals, and textbooks all explained how to destroy the plant, but not how to make it thrive (Field, Durden, and Smith 1952, 149; Hovanec 2019). For a scientist-filmmaker like Smith, the fact that the bulk of available literature was centered on protecting crops from plants like dodder meant that he had to rely on his own experiments to learn how best to grow it under controlled conditions for filming. Attempts like Smith’s to grow, film, and display for entertainment many of the plants, insects, and fungi that were described by scientists and horticulturalists as “pests” produced new epistemologies—ones that treated them as objects of curiosity instead of as targets to be eradicated. But built into popular natural history films was also the potential for a whole visual syntax that classed insects as grotesque—something that was amplified by techniques like microcinematography.

Pesticide companies soon capitalized on the expertise of natural history filmmakers: detailed life histories of insects and other plant parasites were vivid illustrations of precisely the things that pesticides were designed to destroy. An early contributor to the Secrets of Nature series was Harold Maxwell Lefroy, the first professor of entomology at Imperial College London and the founder of the pesticide company Rentokil (Clark 2004; Gay 2012). The Story of Westminster Hall (1925) showcased Lefroy’s efforts to eradicate the death watch beetle that had been eating away at the wooden beams of Westminster Hall in London’s Houses of Parliament. By the 1950s, then, pesticide manufacturers were already familiar with the potential of film to market their products. Natural history filmmakers had already fine-tuned filmic techniques for capturing the life cycles and habits of insects for public audiences, and many of their films had proved highly popular. By drawing on the expertise of these filmmakers, companies like Shell saw an opportunity for selling their new chemical pesticides, all while associating their brand with the positive associations of the natural history genre.

The Shell Film Unit (SFU) was founded in 1934 (Vigars 1984; Burgess 2010; Shell 1999; Canjels 2009; P. Russell and Foxon 2021; Elton 1951; M. Clarke 1994). This came at a time when Shell was expanding its public relations operations, and followed a paper written by John Grierson in 1933 where he recommended that the company should use cinema to promote its identity around the world, while producing films that remained true to the documentary tradition of realism and social responsibility.[1] During the interwar period, films sponsored by corporate or government entities were one of the primary outlets of the emerging documentary film movement, and the SFU soon became one of the movement’s most influential points of reference (Hediger and Vonderau 2009; Boon 2008; Dahlquist and Vonderau 2021; Vonderau, Florin, and De Klerk 2017; Vasudevan 2021). Although the SFU was part of Shell’s broader public relations strategy, its films rarely advertised Shell products directly: remaining committed to realist ideals of the British documentary movement, they sought to capture informative, everyday aspects of a wide range of subjects connected to the oil industry. Films made for the SFU were intended to have an international audience—and in the following decades, they would be translated into dozens of languages and shared with Shell’s subsidiaries around the world. The SFU eventually established local film units in places where the corporation maintained a presence, including in Venezuela, Australia, Egypt, and Nigeria (Shell 1999).

In the UK, the SFU’s films were distributed by the Petroleum Film Bureau (PFB). The PFB was linked to the Petroleum Information Bureau, which produced a Newsletter with statistics and other information about the oil industry. Acting mostly as a lobbying group on behalf of the industry, the PFB also ran stands at exhibitions and agricultural shows. The PFB was primarily a film library, loaning films for free to schools, societies, and other bodies. In 1952 the PFB reported that films from its library were shown 54,417 times, an increase of 10,000 from the previous year (Anon. 1953b). Since 1932 Shell-Mex and BP (the distribution subsidiary for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company) had shared their marketing activities; they also ran a separate film library that loaned films produced by both Shell and BP (Heller 2010; P. Russell and Foxon 2021, 55–56). These were used extensively by the Shell-BP Farm Service, which offered advice to farmers on all petroleum products that could be used in agriculture, including machinery and tractors, petrol, fertilizers, and pesticides. They frequently showed films to farmers’ societies and young farmers’ clubs, and they also owned a traveling cinema that toured rural areas.[2] As an article in The Times from 1958 remarked, the National Federation of Young Farmers had a membership of 68,000, and its monthly branch meetings consistently drew large audiences for film presentations. “Film,” the paper’s correspondent wrote, “is… the ideal medium to maintain interest among the farmers of the future” (Anon. 1958).

In 1950 the SFU released a series of ten short films under the title Plant Pests and Diseases. They were directed by J. V. Durden, an experienced natural history filmmaker who had previously worked for Gaumont-British Instructional, where he shot footage for educational biology films. There, Durden worked under the guidance of F. Percy Smith, and in the years after the latter’s death in 1945, he would continue to refine and develop the techniques pioneered by his former mentor. Cinema, Durden believed firmly, could yield new insights into the workings of biology by capturing images that were otherwise invisible to the naked eye. After the war, he established his own specialist science filmmaking company, Photomicrography Ltd., which produced the films for Shell in 1950. The name of Durden’s company advertised the scientific nature of his production work: as someone who had pursued a degree in science, he wished to carve himself a niche as a specialist scientist-filmmaker, or what he called a “peculiar hybrid, a scientist turned film technician.”[3] To describe his work, he even coined a new term: ciné-biology (Long 2020).

The titles of the ten films included Apple Aphis, Brown Rot, Greenhouse White Fly, Coddling Moth, Raspberry Beetle, and Red Spider. These were all common in the UK, although many were found in other parts of the world too. This made them ideal candidates for a series of films that had to be produced in England but would be distributed around the world through Shell’s film libraries. They were also all insects or fungi targeted by Shell pesticide products. The films provided a sober scientific overview of the life cycle of each subject, focusing especially on helping viewers to note identifying characteristics, while also emphasizing the threat that they caused to crops with close-ups of devoured specimens. Beyond the distinctive Shell logo which appeared at the beginning and at the end of each film (figure 7), however, there was no direct mention of the company’s products.

As was the case with the Shell Photographic Unit’s images, achieving accurate color results was instrumental in Durden’s films. During production, Durden reportedly shot over twenty thousand feet of 16mm Kodachrome stock (Durden 1950). Durden’s papers at the British Film Institute in London reveal the filmmaker’s extensive experimentation with color exposure in the late 1930s and early 1940s, including frequent exchanges with the laboratories of Dufaycolor and later Kodak relating to color balance or exposure issues. Previously he had helped to film sections of the first color series of Secrets of Life that was released in 1939, using the Dufaycolor process. In 1947 he reviewed three entomological films about pest control shot in color:

The filming of insects is a tricky job and continually calls for the exercise of ingenuity; colour adds problems which are yet to be solved… With, as yet, no firm criteria by which to judge colour films of entomological subjects, one can hazard the opinion that the general level of photography in all these productions is high. (Durden 1947)

Durden could speak from experience: in fact, he was halfway through the production of his own color films for Shell, which were first commissioned in 1946.

During the production process, Durden collaborated with H. G. H. Kearns, who at that time was head of entomology at the Long Ashton Research Station in Somerset (Anon. 1987). Kearns was a specialist in crop spraying, and developed new methods of pesticide application (Kearns and Marsh 1937). Kearns’s contribution to the films reflected the close alliance between companies like Shell and state-funded research institutions like Long Ashton. Cooperation between industry and state actors blossomed in the years immediately after the Second World War, when increasing the productivity of domestic agriculture became a national priority (S. Clarke and Lean 2022, 39). Long Ashton worked closely with chemical manufacturers, whose products they often tested at its facilities (Wallace 1953). Shell also had an existing relationship with Long Ashton through the SFU: H. G. H. Kearns appears in the credits to the film Fruit Protection (1939) as “Chief Adviser,” and the facilities at Long Ashton had also been used to make another film, How to Spray (1946).

New products, new audiences

Who were the Plant Pests and Diseases films aimed at? A press release stated that they were “primarily intended for agricultural and entomological students,” but also suggested a wider audience:

Farmers and commercial growers who wish to know as much as possible about a main cause of crop losses will welcome the opportunity to see these films. Horticultural societies and teachers of rural science will also find them of great interest and value. (Shell 1950)

In the following years, the films were shown to audiences across the UK, mainly at events staged by horticultural or farmers’ societies. These screenings were advertised in local newspapers: in March 1951 the Scottish Fruitgrowers’ Research Association showed six of the films, accompanied by a lecturer from Shell Chemicals, J. O. Higley (Anon. 1951b). Figure 8, meanwhile, is an advertisement for a showing of films to a local horticultural society. I have traced similar screenings to Australia, Canada, and Singapore (Anon. 1952, 1953c, 1951a). Like the photographic unit’s images, moreover, they seem to have enjoyed a long shelf life, remaining a popular feature of Shell’s international film library almost twenty years after their initial release (Coelln 1968).

Durden’s films were principally viewed as “educational.” Stills from the series were printed in Andrew Buchanan’s 1951 book The Film in Education, which documented the efforts by filmmakers and teachers to develop a new genre of instructional cinema over the preceding decades (Buchanan 1951). All ten Plant Pests and Diseases films were structured much like an informative lecture: first came a brief description of the subject and its host plant, followed by a more detailed illustration of the subject’s life cycle, before concluding with an animated diagram summarizing the main points (figure 9). Durden used the full range of scientific filmmaking techniques available at the time, including time-lapse cinematography to show insect development or the spread of fungi over fruit, and the use of microscopy to illustrate details such as the germination of spores. As with the photographic unit’s work, color was central to shaping the films’ claims to scientific accuracy. The narrations often referred to specific features that could only be viewed thanks to color—for instance, Apple Aphis includes a time-lapse sequence of the insect’s eggs maturing from a yellow to a shiny black color before they hatch. Above all, the detailed color close-ups reinforced the notion of these insects as real, grotesque creatures with catastrophic consequences—they were a farmer’s nightmare represented in high definition and in full color (figures 10 and 11).

One of the principal messages of the films was to highlight the risks that insects and fungi could pose to a healthy agricultural harvest. In Raspberry Beetle, the narration explains that the initial damage caused by the insect could expose the fruit to further deterioration by mold and other infections: “severe infestations… can cause almost total loss of saleable crop” (figure 12). In Apple Aphis, meanwhile, farmers are warned of the potential for long-term damage to their orchards, which could involve “irreparable harm to the growth of the tree.” Most of the films (except for Leatherjackets and Cabbage Root Fly) focus on fruit crops grown in orchards: these were the areas of agricultural production most likely to invest in pesticide control because of the higher market value of their products (S. Clarke and Lean 2022).

Both the photographic unit’s photos and Durden’s films were employed widely in Shell’s efforts to convince farmers to adopt pesticides. In the summer of 1954, Shell Chemicals launched a traveling exhibition called Battle for the Harvest, which stopped at all the major British agricultural shows. Employing the full range of visual materials at Shell’s disposal, the exhibition portrayed, as one newspaper described it, the “unceasing competition for food between man and insect” (Anon. 1954). Using detailed and highly magnified images provided by the photographic unit, the exhibition adopted a similar pedagogical approach to that of Durden’s films, with the majority of the space focused on describing the life histories of individual species. This was followed by a section showcasing Shell’s range of pesticides and their uses, including photographs that claimed to illustrate the effects of employing pesticides on real farms. Parked beside the exhibition was a mobile cinema van, where visitors could watch Durden’s Plant Pests and Diseases series.

For companies like Shell, agricultural shows represented one of the primary ways of engaging directly with the farming community. Originating in the mid-nineteenth century, they brought together farmers, manufacturers, amateurs, and scientists, and were closely linked to the idea of education as a driver of agricultural innovation (Miskell 2012; Walker 2010). By the mid-twentieth century, they were attracting a wider public, with hundreds of livestock competitions taking place alongside fairground-style entertainments. They were also increasingly dominated by the presence of large corporations eager to promote their various wares and contraptions directly to farmers.

Shell’s 1954 exhibition blended into this scene, appealing to a growing thirst for the spectacular at agricultural shows. Advertisements in local newspapers directed visitors to the Shell stands, telling them to expect “up-to-date scientific and practical exhibits” (figure 13). Figure 14, for instance, is an example of an exhibit by Shell Chemicals at the end of 1954. Dominating the photograph is a large model of a wireworm, the larva of a beetle species whose hosts include potatoes, cereals, and roots. The worm has been given two large backlit eyes and menacing anthropomorphic features and is holding a pickax. It bears a resemblance to an illustrated newspaper advertisement by Shell Chemicals from the same year (figure 15) that showed a group of wireworms industriously feeding on potatoes below ground. Crucially, the potato leaves showing aboveground seem healthy and undisturbed. The advertisement was for Dieldrex, a pesticide mixture containing Dieldrin. Across this wide range of multimedia marketing, Shell’s strategy remained the same: to render starkly visible the effects of “pests” on common crops—effects that might otherwise go unnoticed by farmers.

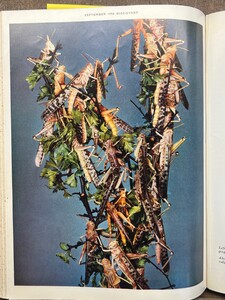

The “man versus pest” narrative of the 1954 Battle for the Harvest exhibition preempted the messaging in one of Shell’s best-known documentaries of the era. Referred to by one contemporary as “the jewel in the crown of Shell’s output” (Giesler 1997), The Rival World (1955) was directed by the Dutch documentarian Bert Haanstra. The film reworked many of the same themes that characterized the Battle for the Harvest exhibition and amplified them to a global scale. Filmed in Kenya, Sudan, and Egypt, The Rival World was a major production that gave a dramatic account of the relationship between insects and human beings (P. Russell 2007, 170–71). Its subject was the threat posed by insects to human health and to food security, told through three main examples: the tsetse fly’s transmission of sleeping sickness, the anopheline mosquito’s spreading of malaria, and the impact of locust swarms on agricultural crops. The second half of the film shows the damaging effects of a locust swarm, and the methods available for their containment. Eschewing the dry instructional tone of Durden’s entomological films, the narration in Haanstra’s film was lurid and alarmist, with bellicose language comparing insects to “armies” that require “counter-measures on the scale of a world war.” It included several sections comprising fast cuts between close-up shots of different insects devouring food and human efforts to curtail their spread. Large parts of The Rival World borrow from natural histories of the era: the film features shots from the life cycles of various insects, and several sequences show their development in time-lapse, including the locust’s transformation from juvenile “hoppers” to fully-fledged flying adults. Ronnie Whitehouse, an assistant cinematographer on the film, described how the production team often relied on the expertise of Woodstock Farm, who lent the SFU specimens that could be filmed by Sidney Beadle in London (Lawson 1998). In figure 19, Beadle and Whitehouse can be seen working together, using large glass beakers of water to illuminate living insects without causing them to wither and burn. As with much lab-based natural history filming, and ironically for a film of this nature, the filmmakers’ skill lay largely in keeping the insects alive.

One of the most dramatic sequences in The Rival World shows an airplane flying directly into a cloud of locusts. As the insects smack and splatter on the plane—window wipers barely able to maintain a line of sight for the pilot—we see a cloud of orange chemical being sprayed into the atmosphere (figures 16 and 17). This sequence is contrasted, before and after, with images of local people trying to contain a potential swarm by attacking the young “hoppers” with branches—a method the narrator brands “hopeless” (figure 18). The film concludes with a discussion of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation and its ambition to “replace the battle of bare hands by modern strategy and materials.” The message couldn’t be less subtle: it paints the tools of Western civilization—pesticides, chiefly, but also airplanes, communications technologies, and intergovernmental institutions—as proven solutions to the problems of disease and hunger in colonial and former colonial lands.

The film is characteristic of the postwar moment of colonial development. With the end of the Second World War came a newfound optimism that organizations like the United Nations would begin to resolve major world problems including hunger and poverty—and that the impetus and resources for change would radiate outward from former colonial powers like Britain and the United States. This postwar “peacetime” optimism often resulted in the erasure of ongoing conflict and violence, particularly of anticolonial liberation struggles, something that becomes apparent when we take a closer took at the production of The Rival World. The locust sections of the film were shot in Kenya in 1954, precisely as the Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960) was entering one of its most intense periods (Elkins 2014). Operation Anvil, which began in April 1954, saw around twenty-four thousand people detained and placed in camps (Bennett 2013, 24–25). In fact, some of the locust sequences were filmed at one of the multiple internment camps established by the British authorities. In all likelihood, the people that we are led to believe are farmers swatting locusts with their “hopeless” sticks are in fact displaced, imprisoned people recruited (or coerced) to take part in the film (Lawson 1998).

British locust research was intimately linked to colonial and imperial interests, especially attempts to increase the productivity—and profitability—of colonized land. Locust research became a key field of British “imperial entomology,” directed since the 1920s by scientists in London’s Imperial Institute of Entomology and Anti-Locust Research Centre (Worboys 2022). During the war, locust swarms posed a threat to Allied aircraft, making research into their eradication a matter of military importance too. In 1948 the Desert Locust Survey was established under the East African High Commission, with a Desert Locust Control Organisation being set up in 1950 to actively fight swarms. It was the large-scale antilocust activities of this organization, which were part of a broader trend in colonial “development” after the war, that were represented in The Rival World (Worboys 2022).

The Rival World would become one of Shell’s most successful films: it was dubbed into twenty-seven languages and distributed around the world through Shell’s subsidiaries (Canjels 2017, 63). It was the first film made by the SFU that employed the new Eastmancolor process, which added to The Rival World’s association with cutting-edge filmic technology. Following its release, it was added to Shell’s traveling exhibition, which was renamed The Rival World. In addition to photographs and diagrams, these exhibitions also featured live locusts on display (Anon. 1956a). The new exhibition included two separate cinemas: in the main cinema, visitors could view the dramatic battle between humans and insects served up in The Rival World; in a cinema van outside, the Plant Pests and Diseases films were shown continuously (Anon. 1956b). Despite occasional alarmist newspaper reports (Anon. 1953a), locusts posed no risk of direct harm to British farmers. Nevertheless, locusts were an obvious conduit for pesticide companies selling their new products: these large and voracious insects epitomized everything that farmers were expected to fear from the category “pest.” By depicting the fight against locusts in East Africa as a pesticide success story, moreover, Shell may have hoped to associate its products with an image of safety and reliability in the eyes of farmers, to reassure them that chemicals tested in far-off places against biblical plagues could be made available for their more quotidian needs.

Conclusion

Douglas Gordon, who assisted Bert Haanstra in the editing of The Rival World, later directed his own locust film, The Ruthless One (1958), this time a collaboration with the Anti-Locust Research Centre in London. Reflecting later on the impact of The Rival World, he said that “it was through Shell Chemicals, largely, that [the SFU] got into this whole area of environmental impact of science and technology” (Giesler 1997). This is an interesting observation, and one that we should incorporate into analyzing recent attempts by large players in the fossil fuel industry to greenwash their public images. Greenwashing by major fossil fuel corporations may seem like a relatively recent development, but in fact Shell has spent the best part of the past century trying to spin its activities as good, clean, and natural. The films and photographs that I have discussed in this essay should be considered within this larger context. Over the following decades, the SFU would produce numerous films that touched on “global” and “environmental” issues, including The River Must Live (1955), The Threat in the Water (1968), an updated reissue of The Rival World (1974), For Want of Water (1983), and Climate of Concern (1991) (Burgess 2010, 222). This last film described research by environmental scientists into greenhouse gas emissions and their effects—the introductory Shell logo today seems especially conspicuous, given the company’s climate record over the ensuing three decades.

Films and photographs made by Shell after the Second World War illustrate the way that mass media technologies were harnessed as powerful storytelling tools on behalf of extractive capitalism in the mid-twentieth century. Shell’s public relations in the 1950s made a great deal out of the fact that its business activities centered on the extraction of raw materials from the earth. But the narrative that it told about these activities painted petroleum and its chemical by-products as clean, modern, and socially beneficial. In the case of pesticides, it would not be long before the truth about their disastrous environmental impacts became clear. In the unusually dry spring of 1960, a vast decrease in wild bird populations was attributed to the ingestion of seeds that had been coated with pesticides. Aldrin and Dieldrin were soon identified as some of the worst offenders. Despite growing pressure on Shell to cease selling both products, it was not until 1964 that it was forced to remove them from horticultural use, with agricultural applications severely limited. This delay was in no small part influenced by the fact that Lord Victor Rothschild, the head of Shell Research, was also the chairman of the Agricultural Research Council (Gay 2012, 95). Such delays enabled Shell to continue marketing products into which the corporation had invested millions of dollars and decades of research, but they flew in the face of mounting evidence about the potential for harm inherent in pesticides. Much of this evidence originated in research produced by Shell employees and researchers at Woodstock Farm (Christie and Tansey 2004). Managers at Shell were therefore well aware of the dangers that pesticides posed—and evidence collected by their researchers was used to delay rather than support the introduction of pesticide regulation.

After the dangers of chemical pesticide use became more widely known—particularly following the UK publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1963—alternatives to pesticides were increasingly sought out. In the late 1960s and 1970s, for instance, biological methods of controlling insect damage would be more widely studied as alternatives to chemical application (Gay 2012). Biological control, however, was not a new discovery. The Pest, a 1945 film partly filmed by F. Percy Smith and sponsored by Pest Control Ltd., showed how ladybird grubs could help to control blackfly populations—but argued that a nicotine spray could do the job much quicker. A sequence in The Rival World, meanwhile, shows how ladybirds can be used to combat the mealy bug family of insects. Scientists are shown collecting the ladybirds into test tubes in a laboratory, before shipping them by airplane to fields in Kenya. However, the narrator is scathing of this form of biological control: “The trouble is, that ladybirds take time to work. That’s why man’s greatest ally in this endless fight is his study in the field of chemistry.” The film left viewers with the impression that the only viable solutions to global shortages were insecticides of the kind marketed by Shell Chemicals. Similar methods of biological control were occasionally shown in Durden’s Plant Pests and Diseases films, such as Greenhouse White Fly (1950). However, biological methods were not widely adopted because the messaging forcefully touted pesticides as the more modern and efficient method of combatting infestations.

The products that Shell marketed with the use of color photographs and films in the period following the Second World War—petrol, pesticides, fertilizers—were key components of the postwar developmentalist solution for colonial and former colonial places. Success stories about the use of pesticides in defeating swarms of locusts or eradicating malaria endowed agricultural chemicals with a sense of urgency and importance that Shell capitalized on in its public relations and marketing strategy. Whether it was glossy photographs printed in corporate pamphlets or films screened in mobile cinema units, Shell cultivated a global brand that equated Western modernity with moral virtuosity and progress. A key part of this strategy was the creation of still and moving images with a high production value. The thousands of high-definition color images of individual insects produced and circulated by the Shell Photographic Unit and the detailed films made by J. V. Durden formed part of a campaign by chemical companies to render visible a problem to which the only solution offered was the intensive use of pesticide products. Borrowing from the natural history genre of photography and film, these images normalized and naturalized the use of pesticide chemicals in agriculture without needing to directly name the products that they were designed to sell. In doing so, they helped to construct an image of “the pest” that farmers could easily recognize as a target to chemically vanquish. Indeed, before sprays, seed coatings, and dusts could be sold, insects had to be construed as living, healthy, hungry, and menacing threats to the farmer’s crop.

The paper does not survive but is widely cited in histories of the SFU.

Traveling vans of this description were used to reach farmers in rural places around the world. See Druick 2012; Goode 2018.

J. V. Durden to A. Pijper, n.d., BFI National Archive, J. V. Durden Collection, box 1, book 1. Film Productions, 3/3.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)