Introduction

<JRC>

The idea of a distant, dangerous, haunted, or enchanted island lurking at the edge of a small flat Earth is common to early Western maritime cultures. Homer conceived of the world as a small flat surface entirely bounded by a narrow river known as Oceanus. At the outer edge of this world, the Cimmerians live in mist and cloud. Horizon blends into sky. The Sirens attempt to lure sailors to their island with their singing voices. In early depictions, the Sirens are portrayed as terrifying creatures. An Attic-ware vase from 480 BC, now held at the British Museum in London, depicts the Sirens as large birds with women’s heads, their lips parted as if singing.

Since the first European voyages across the North Atlantic to the rich cod-fishing grounds off the east coast of Newfoundland, there have been reports of an Island of Demons in the region, inhabited by a curious mixture of seabirds and wild animals, mythological creatures and evil spirits, frozen tides and howling winds. In 1542, Sieur de Roberval, viceroy of Canada, sailed from La Rochelle, France, for Newfoundland with three ships and two hundred colonists. He is said to have cast his niece Marguerite ashore on the Island of Demons. She is said to have survived this ordeal for two years and five months before being rescued by passing Basque fishing boats and returned to France. According to French royal cosmographer, explorer, scholar, and Franciscan friar André Thevet:

I have been told so by not just one but by numberless pilots and mariners with whom I have long travelled; that when they passed by this coast, when they were plagued by a big storm, they heard in the air, as if on the crow’s nest or masts of their vessels, these human voices making a great noise, without their being able to discern intelligible words […]. These voices caused them a hundred times more astonishment than the tempest around them. They well knew that they were close to the Isle of Demons…. (Schlesinger and Stabler 1986, 61–62)

There is no material evidence extant to support this story. It propagated in part through the lingua franca of superstitious sailors, in part through the rampant copying prevalent in early modern European print culture. There are echoes of Thevet’s account in Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1996). When Prospero asks the spirit Ariel: “Performed to point the tempest that I bade thee?” (70), Ariel replies:

…Now on the beak,

Now in the waist, the deck, in every cabin

I flamed amazement. Sometime I’d divide,

And burn in many places. On the topmast,

The yards, and bowsprit…. (1996, 70)

Striking, in these and other accounts of the Island of Demons (Carpenter 2012, 2015), is the intermingling of voice with weather, wind in particular, and the otherworldly. In Wonder & Science, Mary Baine Campbell notes that “Thevet fails to identify his demons as native people engaged with one another” (1999, 36). White settler colonial narratives have ignored or violently silenced the voices of the Indigenous Beothuk, Dorset, Inuit, and Mi’kmaq inhabitants of the islands in this region for over a thousand years. In Hungry Listening (2020), Dylan Robinson critiques a colonial mode of listening that centers the white settler listener. In Douglas Glover’s novel Elle (2003), the white settler Marguerite remains the focal point of the narrative. A central question for me, throughout this research, has been: How can I, as a migrant, born of immigrants, born of emigrants, contribute to disrupting or dislodging deep-seated settler colonial narratives?

In 2013, the British Library released over a million images to Flickr Commons. The images were scanned from the pages of sixty-four thousand books published in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, at the height of British Imperialism. Wolfgang Ernst observes that an old radio tuned to receive new signals “is not a historical object anymore but actively generates sensual and informational presence” (2011). And what of an old image, digitized and published online for anyone to use however they wish? Free now of copyright and divorced from the historical context of the surrounding book, these newly digitized images actively generate colonial affect. Maja Maricevic, head of higher education and science at the British Library, has said, noted in an in-conversation event following a live performance of An Island of Sound at the British Library that took place 7 July 2023, that AI trained on the British Library’s Flickr Commons returned racist results.

How might the affordances of a lo-fi, handmade, browser-based digital artwork disrupt the colonial organizational principles upon which this archive is based? Intermittently, over a period of seven years, I scrolled through this archive looking for images that obliquely evoked but in no way illustrated a cluster of associations around phantom islands. The result is a sprawling and disorienting digital collage, built in bits and pieces, toward a new semantic web of associations.

In June 2022, I was commissioned by Edinburgh Futures Institute at University of Edinburgh to create a new performance for their First Breath event series. The series curator, Ioannis Kalkounos, asked me if I might like to collaborate with someone from the university. Perhaps a data scientist, he suggested. Or a musician! I replied.

</JRC>

<JRA>

We began our collaboration by sharing resources, links to work in progress, recordings of prior work, and suggestions for reading and listening, toward finding common ground.

Treating the visual aspect of the browser-based work as a graphic score, I sourced and mapped sounds to images, curating a selection of sounds that are environmental, animal, and mechanical in character, and that explore the geographical, environmental, formal, and material qualities of the images. There’s an ambiguity to the mapping, created through the combination of real-world, musical, and synthesized sounds, which critically allows for a more-than-human recolonizing of the spaces and places in the work.

As with the images, the core recorded material for the work’s soundscape is archival. The sonic documentary of places, spaces, species, and weather created by the BBC’s Natural History Unit is available for personal and research use on the BBC Sound Effects Archive. There’s also some use of recordings from Freesound, a collaborative database of Creative Commons Licensed sounds, and of recordings from the British Library’s wildlife and environmental sound archive.

When I looked at the source code, the narrative themes of the digital writing suggested opportunities for more abstract sound treatments portraying migration, navigation, displacement, and isolation, together with ever present weather. The soundscape in the work is “schizophonic” (Schafer 1977), split between original sound and location and the place of its transported reproduction. As with the images, sounds are collaged, dislocated, re-placed, and recontextualized.

Some reference points for the creative development of the soundscape include the collaged environmental field recordings providing a narrative of place on Chris Watson’s Weather Report (2003) and El Tren Fantasma (2011). Less representative, more abstract musical examples that investigate environment and weather through sound include Olivia Block’s Heave To (2006), where field recordings of wind and rain are accompanied by electronic sound and chamber orchestra imitating the field recordings, and Sabine Vogel’s Aus Dem Fotoalbum Eines Pinguins (2006), which makes use of extended flute techniques to create impressions of polar windblown resonance.

The sounding of voice, weather, place, and material in the work is explored through “source bonding” (Smalley 1997), apparent relationships in sound due to appearance of shared origin, context, or cause. The digital writing provides faktura, details of material essence and texture, and in dealing with wind, the Beaufort scale outlines physical manifestation through spindrift and spray, rustling leaves and whistling wires, and also describes the destructive nature of wind.

Working between presentation and representation, the overall sonic discourse has been abstracted from the images and text to evoke experience and suggest alternative interpretations, fictions, and speculations, and makes use of hybrid soundscapes that include imitative rendering and impressions of naturally occurring characteristics of interactions between wind and environment, and representations of colonial activity and impact.

</JRA>

<JRC>

How to find a shared path through this amalgam of audio, visual, textual, and algorithmic materials? How to excavate a performance script from the JavaScript source code (Carpenter 2017), flatten the near infinite possible textual alternatives into a form fixed enough to provide direction for a journey across and through the browser-based work, but open enough to allow for moments of extemporization?

“I know, I’ll write a book!” I said. A week later I sent JRA a fifty-page document that I referred to as a performance score, but which I was already thinking of as a poetry collection.

“Ah, a libretto!” he said. “Something I can work with.”

</JRC>

The Libretto

swallows (an overture)

[The audience enters the performance space to the sound of sea swash.]

[A black and white image of a woodcut engraving of a single swallow in flight appears at the top left corner of an otherwise blank white screen.]

five thousand nautical miles.

a swallow. [loop]

five thousand more.

a swallow.

five thousand back.

a swallow.

safe.

a swallow.

and repeat.

and swallow.

ten thousand wings over the ocean.

and breathe.

ten thousand wings round the cape.

and breathe.

swallows up my arms.

and breathe.

<JRC>

The overture of the libretto evokes the swallow as a figure of radical migration, travelling five thousand miles twice a year in search of food. For its association with way-finding and safe return, the swallow has long been a ritual tattoo for sailors. The implied meaning soon shifts in this text, from the name of a bird to the act of swallowing, to exhalation, as breath. The figure of the swallow evokes an intermingling of avian and human bodies, of arms and wings, of wind-borne wings and wind-powered sailing ships, of oceanic wind currents and the more minute circulation of air in and out of lungs.

</JRC>

<JRA>

The live performance of An Island of Sound begins with an act of temporal displacement. The short phrase “a swallow” is recorded and subsequently looped throughout the remainder of the overture. Silence and sound are framed such that when the looped phrase repeats against the spoken lines, which include further spoken instances of “a swallow,” a sonic image of a pair of swallows circling and wheeling on the wind is created. The loop multiplies to a polyphonic texture suggesting the flocking motions of “ten thousand wings over the ocean.”

</JRA>

dots interlude

[A new sound element enters the soundscape, a repeating phrase of Morse code transmitted via shortwave radio signal from a “numbers station” sending encrypted intelligence communications that bounce off the earth’s ionosphere.]

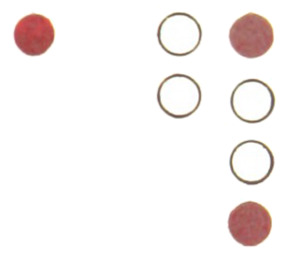

[A horizontally scrolling line of red and white dots appears, moving from right to left across the screen. This line of dots passes over the swallow and keeps going, moving in the opposite direction the eye moves when the eye reads a line of text printed on a page, yet highly suggestive of some form of readable language.]

<JRA>

The repeating phrase of Morse code accompanying the scrolling dots was chosen in part for its abstracted musical qualities of pulse, tone, and accompanying noise. This recording can be heard in a number of ways. Firstly, Morse as birdcall, as the swallow’s song is very staccato. Secondly, the sustained tone as gliding flight pattern, and finally broadband noise as wind and weather.

</JRA>

<img src="images/alphasignals/i.png" alt="i" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/\_.png" alt="\_" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/a.png" alt="a" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/m.png" alt="m" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/\_.png" alt="\_" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/n.png" alt="n" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/o.png" alt="o" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/t.png" alt="t" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/\_.png" alt="\_" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/a.png" alt="a" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/n.png" alt="n" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/\_.png" alt="\_" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/i.png" alt="i" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/s.png" alt="s" width="75" height="266" />

\<img src="images/alphasignals/l.png" alt="l" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/a.png" alt="a" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/n.png" alt="n" width="75" height="266" />

<img src="images/alphasignals/d.png" alt="d" width="75" height="266" />

<JRC>

The lyric reading of the “swallows” text is interrupted by encoded signals communicated through sound and visuals. So, too, this critical essay is continuously interrupted by its own subject. Writing into the libretto structure invites the simultaneous reading of the text as it is performed by the speaking body and the subtext of the source code as it is performed by the web browser. Viewing the page source reveals that each vertical line of dots is a single .png file. The file name and alt tag indicate that each .png file is associated with a letter of the alphabet. Created from a single image from the British Library’s Flickr Commons, of a mast light language used for communication between ships at sea, this dot font is used to write the text in the “fog furies” section of the libretto discussed below.

</JRC>

fog furies

[As the Morse becomes more diffuse and recedes, the spoken text reenters as a preprocessed sound recording of this section of the spoken text, triggered simultaneously with the first word. The process here is of extreme time stretching, causing the chant-like measured delivery to become rolling waves of sound that become uncanny echoes of the spoken part.]

I am not an island

swallow ship demon

not so fast easy

to chart name

measure me

type cast me

away aside adrift ashore

nor am I lit

by gas star or far

moon light alight

a light atop a foremast

turned on or off at

will this sea rise

rage see me

through these

wind wave

wing thick

fog furies

<JRA>

Throughout the work, I’ve taken influence from Berio’s Omaggio a Joyce (1967), montaged electronic manipulations of the spoken sonically evocative and fragmented text that opens the Sirens episode from Joyce’s Ulysses. In JRC’s spoken delivery of her digital writing, there’s a dynamic of performance through interpretation, translation, and expression. The clusters of pulsed intonation often resemble a litany, chant, or incantation. One of the key elements of the collaborative process was finding and making space for sound between words, and of making spaces to set the words in sound.

My sound treatment here recalls Krause’s (2008) observation that the acoustic signatures of beaches are defined by factors of the beach rake and material, the sea’s salinity and temperature, and local weather patterns. Breath and sibilance take on the character of breakers dragging back through shingle, the inflection and timbre of the spoken word creating acoustic variations that are both distant and nearfield. We hear individual sound events, but also the aggregate of these.

Live processing of both the spoken part and the processed recording creates more wraithlike wisps of sound through spectral resynthesis until finally a denser fog bank of sound is formed. Tilt, spray, and microtuning in the fog sound cause a dispersal in the soundscape that mimics the natural sound bending and diffusing effects of sea fog moisture droplets.

</JRA>

<JRC>

The Sirens, at least, stay on their island. Yet more terrifying forces assailed sailors of ancient Greek seas. Born of drops of blood, or of the union between air and earth, or the union between hell and night, depending on whom you ask, or what you read, Erinyes, also known as Furies, were female deities of vengeance, the embodiment of a curse.

In Aeschylus’s Eumenides (458 BCE), Furies pursue Orestes:

over the wide rolling earth we’ve ranged in flock,

hurdling the waves in wingless flight and now we come,

all hot pursuit, outracing ships astern— (1984, 242)

In Excommunication (2014), Alexander R. Galloway suggests that Furies “stand in for complex systems like swarms, assemblages, and networks. The term infuriation captures well the way in which the Furies can upend a situation, thrusting it into a flux of activity and agitation” (29). Furies are an incontinence of form, a swarm, a cloud, a storm, a system, an impossible number of birds screaming overhead.

</JRC>

an island

[The soundscape changes, emerging from the fog bank to the wash of waves on a shore.]

[The screen changes. A horizon appears, inside an illustration of a circle, suggestive of a porthole, or a spyglass, but depicting no land. Only sea, air, and cloudy sky. Seabirds break the frame. If there is wind, we can’t see it or smell it or hear it. But the seabirds can. In the stand-alone browser-based version of An Island of Sound, this is the opening page.]

an island

appears on the horizon

an event. horizon.

at the edge.

of the known.

unknown. unnamed.

not named by me.

a small place. of great size.

at the edge. of a narrow sea.

an island

shrouded. in cloud. and mist

where the sun. never sets

where weather comes from

where wind comes from

an island inhabited by strange creatures

an island inhabited by birds

by a woman

even.

an island

awaits

<JRC>

Hernán Díaz argues that islands have been pervasive throughout literary history because they are a perfect “topic.” The word “topic” derives from the Greek topos, which originally only meant place, but over time came to refer to commonplace motifs in literature. “This is exactly the trajectory of literary islands,” Díaz argues: “They are places that have become commonplaces” (Díaz 2001, 79). In Writing Space, Jay David Bolter argues that with the advent of digital writing, topoi are now located in the data structure of the computer. As such, he writes: “Electronic writing… is not the writing of a place, but rather a writing with places as spatially realized topics” (2001, 36). Our libretto cites some but not all of the islands contained in the data structure of the digital text. The variable “island” calls arguments from a topography of islands collected from classical and early modern texts and maps. The commonplace motif of the phantom island has arisen in large part from topoi related to specific weather phenomena, from drifting icebergs and howling winds to optical illusions resulting from thermal inversion known as fata morgana. The JavaScript stores these topics in arrays of arguments, the libretto selectively displays some but not all of these arguments on the pages, and the live performance spatially reconstitutes this subset of topics within a soundscape.

</JRC>

<JRA>

The soundscape in this section is an exploration of place. Following Voegelin (2010, 144), the soundscape considers place from within, rather than from above as in a projected aerial view such as a map. The audience is placed inside of the initial lapping and wash of waves on the shore through surround sound projection in the performance space.

A time-stretched recording of cello enters the soundfield, an abstracted representation of a gentle breeze. There’s a kinetic element to the sound design, with a moving point of audition. As the text describes the character of the island, so too does the sound. The wind is heard in things, and through things as an act of “psycho-sonic cartography” (Hernandez 2017).

A field recording of a more insistent wind whistling through a gap adds another harmonic layer, before crossfading to a recording of wind, 5 to 6 on the Beaufort scale, blowing across a fence and rattling loose elements. Simultaneously the listener hears a recording of wind flapping and slapping a flag atop a pole with a metallic resonance.

There’s what Andean (2016) considers to be material and embodied narrative to this soundscape. The physical character of these wind-activated objects becomes the “grain” of the wind’s voice, what Barthes defines as the “materiality of the body speaking its mother tongue” (1977, 182).

Through the transmission and translocation of these recordings, there’s an “unfolding” of the past in the present (Voegelin 2010, 4). This is the wind sounding histories of settlement and displacement. This whistling fence was placed to contain or exclude, that flag marks colonial imposition.

Through surround projection, the listener is placed, immersed, into this land and soundscape, between the fence and the flagpole, not hearing the wind, but hearing “in” the wind (Ingold 2007). The challenge here is to balance wind and voice. Or perhaps the voice is subsumed, swept up, and surrenders?

Moving further into the text, further into the island, the unfamiliar squawks and screeches of “demonic” seabirds emerge from the masking and scattering elements of the sounding wind, surface waves, and fog. Other environmental actions of the wind make them stranger still, as the wind, forced through narrow formant-like folds and gaps, creates uncanny aeolian vocalisations of singing, sighing, whistling, and howling.

At times the soundscape undoes or acts against JRC’s desire to decentralize demons, devils, and settlers, but it does so as a way to frame the invisible and uncanny, and to support semantic association.

</JRA>

I land

[The accumulated layers of the preceding soundscape are filtered and attenuated, becoming cloudlike, with irregular and shifting outlines of sound that are in constant motion at different speeds at different heights.]

island I eye you

island I ear you

I hear you

I here you

here you are island

and I island here too

island I you

I island you

I land

I land you

I hand you

over

and you

land you

dry you

dry land

you island you

<JRC>

Building on projectivism’s rejection of the conventional subject position of the epic poet, that of MYSELF, the lyric I, in favour of an archetypal memory, an informatic I, the subject position in An Island of Sound moves towards a more-than-human I. When I write “I,” I don’t always mean me. Sometimes, I refer to a subject position bordering on plural, which is not quite we. I speak not for, but from amidst a more-than-human entanglement. An imaginary topography, an “I land” inhabited by a curious mixture of devils, demons, and mythological creatures. And a real land, inhabited by Indigenous Peoples, animals, and the elemental media of wind, fog, ice, and stone.

</JRC>

<JRA>

This is a moment of stillness and relative silence in which to re-situate and restate the primacy of the voice and evoke isolation by reducing the density and amplitude of the soundscape.

Repetitions in word and sound are abstracted from the repetitions in the text through dynamic shape and delay, and small shifts in pitch that cause ambiguity in who might be speaking.

These delays are representative of wind-formed wave motion, peaks, troughs, and eddies that swirl, diminish, and die away through burst, spray, and fracture creating shifting frames and islands of text, word, sampled voice, and soundscape.

</JRA>

a ship

[The sounds of regular oar strokes disturb and ripple through the filtered ambience.]

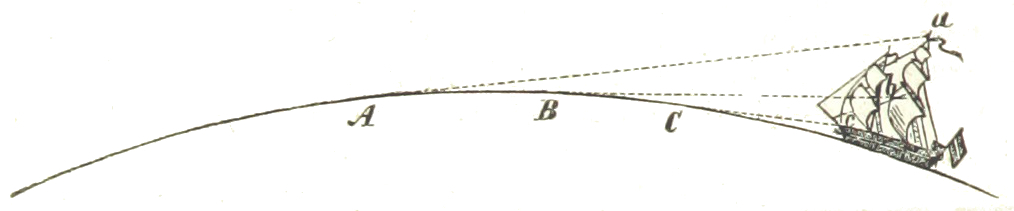

[A diagram from a geometry textbook shows three points on a curved line.]

a ship

sits upriver

waits at anchor

arrives without water

departs without a flag

lists without a sail

speaks at the harbour mouth

stands in the roads

sings on the gusts

floats on the radar

hangs on the horizon

creaks in fair weather

leaks in foul weather

sinks in the strait

sinks in the sound

sounds and finds no ground

<JRC>

Like the island, the ship is a motif so common as to become commonplace. For thousands of years, the ship was the fastest humans could travel, the furthest humans could think. The ship is a metaphor, in the ancient Greek sense, a vehicle moving between places across spaces, linking “spatial trajectories” (de Certeau 1984, 115). Beyond the furthest reaches of the ship, beyond the limits of the human body, beyond as far as the eye can see, in the mind’s eye, there is nothing but danger. From watching their square sails disappear over the horizon, the island-hopping Vikings knew that the Earth was curved, but they believed it was ringed by an impassable sea edged by a furious overfall. The topology of this edge persists into the early modern. Cornelius Wytfliet’s Map of Estotilandia et Laboratoris Terra, 1597, shows a furious overfall at the edge of the Davis Strait.

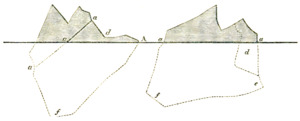

The British Library Flickr Commons contains thousands of innocuous-looking diagrams taken from geometry textbooks. In Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford cautions against the characterisation of data “as something voluminous, disorganized, impersonal, and ready to be exploited” (2021, 107). Decolonisation is a long process of recognising and revealing the integral, structural role of empire in museum and library collections. A closer look at this diagram reveals that the letters A, B, and C represent the distance from a point on the horizon to a corresponding point on a sailing ship: a, b, c, with a being the top of the main mast, b being the mainsail, and c being the deck. The scale for estimating the force of wind devised by Francis Beaufort in 1805 was based on the amount of sail a full-rigged frigate could carry. Beaufort forced every ship in the British Admiralty to collect wind data using this scale. Every time we check the weather app on our phones, we’re evoking the ghosts of data collected under the auspices of wind-powered colonialism.

The curved line in the diagram represents the surface of the Earth. Or ocean, as the case may be. If you’re a sailor on watch in the crow’s nest atop the mainmast at point a, then A = land. If, on the other hand, you’re an Indigenous Person standing at point A, then the sight of point a, coming over the horizon, spells trouble. Refusing the notion that scientific imperialism is objective or neutral, here the lo-fi digital collage disrupts colonial organizational principles by acknowledging and problematising colonial affect, rather than glossing over it.

</JRC>

<JRA>

The soundscape crossfades through a range of recordings of sea craft, from the small, rowed boat, to a barge, and a larger craft under sail, each time moving the point of audition further out to sea. The listener hears creaks and knocks, the snap of wind in sails.

A ship’s timbers affect timbre, vibration, and sound transfer, and changes in temperature and humidity can alter sounding character. Sailors might be able to anticipate changes in weather by the sound of “tones of wind amongst the rigging and the spars and over the bulwarks” (Ross, in Piddington 1848), a binding of medium, surface, and substance.

</JRA>

the question of scale

[Amid a cluster of images—of a small ship, a large wind rose, a massive wooden fishing hook, and a coil of fishing line—a single line of variable text appears at a ninety-degree angle to the horizon, forcing the reader to shift perspective. The libretto contains but a fraction of the possible variations.]

the question of scale

is a colonial imposition

preoccupation with proportion

is a colonial fantasy

insistence on measurement

is a colonial violence

<JRC>

Sybille Krämer observes that cartography underwent a profound reformation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: “map producers abandoned the elaborate and fantastic projections created in their studios and exchanged them for fieldwork in a landscape whose topology was exactly quantifiable” (2015, 188). Through the operations of measurement and direct observation, the topology of a quantifiable new world was written over the surface of a landscape that had already been known to its inhabitants for tens of thousands of years. The map became a symbolic representation of a terrain that it strove to approximate exactly. An Island of Sound aims to disrupt this assumptive relation.

My only rule in working with the British Library Flickr Commons images was that I would use them in whatever size they came in, resulting in an entirely unquantifiable topology. In Hungry Listening, Dylan Robinson asserts that settler colonial discourses “sanitize the sharp edges of difference” (2020, 145). An Island of Sound leans into what Robinson terms “the uncertainty of radical difference” (216). Through juxtaposition, contrast, and rupture, scale is continuously called into question. This unquantifiable topology continuously reminds the reader/viewer that these images are the detritus of Empire: islands and their measure, ships and their treasure, trees and the breezes that bend them, seeds and the winds that scatter them, birds that soar upon the winds, and so on.

I list because wind is relentless, and excessive. As is Empire. Even calm, no wind, is a category of wind.

</JRC>

<JRA>

Sound in this work is often revealed through manipulation of scale. Singing aeolian vibrations, wind-blown harmonics from fences and cables captured through contact microphones are made audible through high-gain amplification. These amplifications comment on the unseen and unheard presence of naturally occurring sounds at both infrasonic and ultrasonic ranges that humans can’t detect but other forms of life can.

Working forwards from Roads’s (2001) theories of “microsound,” concepts of temporal scale can be applied to spoken word, sounding temporality and transience though sibilance, plosive, fricative, phoneme, syllable, word, sentence, and stanza. This is the sound at the scale of breeze, gust, and gale, breath, sigh, and swallow.

</JRA>

beads

[Maritime sounds give way to the tinkle of small windblown chimes and beads.]

[A string of red beads extends from one line of a geometry diagram extending from a shape resembling an island.]

an old habit

of stringing together

beads of bone, jade, coral

real beads, glass, mineral

trade beads, seed beads

smallest beads of ivory

shell, quill, wooden beads

beads of prayer and sighing

beads of waiting

and of wanting

<JRA>

Wind chimes may be among the earliest of generative music systems (Dorin 2001). The scale of sound here is natural and delicate at the outset, but the sound becomes increasingly amplified, distorted through waveshaping, pitch-shifting, and multiplication, an emergent system.

</JRA>

<JRC>

Onscreen, a variable text dispassionately lists individual types of beads. On the page, the libretto presents multiple beads in a cluster of fraught associations. The phrase “beads of prayer” evokes the rosary, and thus the Catholic Church, and “trade beads” evokes the Hudson’s Bay Company. Both these institutions were perpetrators of systemic violence against Indigenous People for centuries on Great Turtle Island.

</JRC>

leave away then

[A crossfade in sound between the chimes to more full and low register organic bursting and popping sounds.]

[A slow horizontal scroll across a diagram of a mineral supporting a single stand of palm trees, continuing across a double line of pale seed pod shapes, each lettered according to a convention of scientific referencing.]

leave. away then.

race. run. venture.

cast off. dash off. lift off. shy.

with beans. seeds. grains. peas.

slipped. stitched. sewn.

in hems. cuffs. linings.

<JRC>

Colonists often brought seeds with them. Thinking through the elemental media wind, we may consider seeds themselves as colonisers. In Islands of Abandonment, Cal Flyn describes the process of botanical colonisation of barren, newly formed volcanic islands through “primary succession”—lichens, pollen, and seeds are “blown in on the winds, or spread by birds, or in the droppings of animals (what ecologists call, poetically, ‘seed rain’)” (2021, 22).

It must be said that some would-be settlers were unwilling participants in the colonial project, transported to distant islands without their consent. In decentralizing the quasi-historical figure of Marguerite, An Island of Sound creates a wider space for consideration of power relations in situations of abandonment, escape, and survival.

</JRC>

visited. assailed. assaulted.

by debts. devils.

lies. lies lies lies. [loop]

challenge these.

escape. refuse. survive.

<JRA>

The sustained organic highly amplified bursting and popping microsounds aim to bond the soundscape to the text, images, and spoken word. There’s a return to processes of live capture and looping such that what is heard is “challenge these [lies lies lies]. escape [lies lies lies]. Refuse [lies lies lies]. Survive [lies lies lies].” As with seeds blown on the wind, other kinds of particles can form and reform, sand for example creating shifting dunes, and the looping creates these masses.

</JRA>

[ bit of a rant ]

[A line of variable text generates an ongoing critique of colonial archives, running vertically alongside an artificial edge of half a map of the British overseas territory of St. Helena, site of Napoleon’s second exile. The digitally archived island has been doubly severed, firstly by the spine of the book, and secondly by the automated scanning process.]

a few. arguments. certain. assumptions. could. colonial. geographies. have. fixed. positions. may. early. ideas. eventually. many. readings. over time. certain. stories. can. topographies. may. precise. processes. might. some. routes. might have. these. schedules. could have. trajectories. occasionally. often. will.

become arrested. by breaks. attracted. by creases. complicated. by folds. convinced. by gaps. deluded. dislodged. distorted. disrupted. by slices. distracted. by splits. seams. stains. nuanced. in the archive. seduced. in the atlas. startled. in the body. roused. by data. troubled. by island. buffeted by wind. in the ocean. become page. by text. in the error. become. interrupted. by map.

<JRA>

The disruptions and fragmentations of this section of spoken word are magnified by real-time sound processes. Small sections of audio stick and skip in unpredictable ways, foreshadowing the arrests, breaks, creases, folds, splits, and seams outlined in the second paragraph.

What was unexpected, and highly engaging, in developing and rehearsing this sound treatment was how JRC would adopt and inhabit the digital process in delivery, stuttering, delaying, and disrupting her own voice in imitation of the effect. This stuttered and processed reading furthers the disruption of the colonial organizational principles that the text itself critiques.

</JRA>

manoeuvring

[Soundscape shifts to the interior of a modern trawler.]

[Three lines of variable text at a right angle to the horizon intersect with an image illustrating five types of navigation markers.]

<JRC>

The first line of text contains code words from the International Code of Signals for the Use of All Nations (ICS), first published in 1855. Mariners use these codes in combination to signal through the elemental media of air, visually (through alphabet flags, semaphore flags, and flashing mast light, as seen in the dots interlude), and sonically (by sending Morse signals by means of siren, whistle, foghorn, bell, or other apparatus).

codeflags.introduce_plug('oneword', new SwitcherPlug([

'Yes','No','Alpha','Bravo','Charlie','Delta','Echo','Foxtrot',

'Gold','Hotel','India','Juliet','Lima','Kilo','Mike','November',

'Oscar','Papa','Quebec','Romeo','Sierra','Tango','Uniform',

'Victor','Whiskey','X-ray','Zulu' ]));

The second and third lines deconstruct the standard textual descriptions of these codes. This operation occurs within the JavaScript source code. On screen, the reader will only ever see one line at a time. In the source code, arguments for the variable ‘i’ are arranged in a long poem, the first four tercets of which are shown below:

codeflags.introduce_plug('i', new SwitcherPlug([

'I am taking in dangerous goods',

'I am carrying dangerous goods',

'I am discharging dangerous goods',

'I am taking',

'I am carrying',

'I am discharging',

'I am dangerous',

'I am good',

'I am',

'I am manoeuvring',

'I am manoeuvring with difficulty',

'I am difficult',

My use of the ICS is informed by Hannah Weiner’s Code Poems (1982). Playing on the occurrence of proper nouns in the ICS, Weiner combines codes and names to create off-kilter dialogues between Romeo, Juliet, and Mike. My approach blurs the ICS’ already murky distinctions between the subject positions “you” and “I.” The subjects—ship, captain, speaker, listener, anchor, and fire—all speak from the same plane of immanence within a machinic assemblage of enunciation. In the libretto, the tercet is abandoned in favour of alternating lines of dialogue indicated by indention. This syncopated, more-than-human, part machinic “I” emerges in fragments.

</JRC>

I am manoeuvring with difficulty

I am difficult

I am altering my course to starboard

I am my course

my vessel is making no way through the water

I am my vessel

you should stop your vessel instantly

watch out for me

I am hauling nets

I am trawling

I am dragging

I am anchor

I have a dangerous cargo on board

you are running into danger

keep well

keep well clear of me

I wish to communicate with you

communicate with me

I am on fire

I communicate fire

I am fire

I wish

I have a diver down

I am a diver

I am diving

I

dive

down

<JRA>

In the trawler recording, the listener hears the regular filtered drone of the motor as an atmosphere layer, growing in urgency as the speed increases, and there’s ambiguity in terms of habitat and feature layers, the ship rocking with the weather. The sounds of trawlers and other forms of shipping have a profound effect on marine species, causing them to manoeuvre with difficulty.

The final sonic element in this section is of a highly amplified aeolian harp that sounds at the end of the section with “diver down,” growing in intensity as the other elements fade out. In combination with the repetitive, harmonic, and somewhat plaintive “song” of a humpback whale, the soundscape is both siren signal and Siren song and asks, “Who or what is the diver here?”

</JRA>

but not without peril (a refrain)

[The guttural sounds of guillemots, shearwaters, and cormorants emerge out of the spectra of the distorted aeolian harp and become frighteningly overwhelming.]

[Two lines of variable text fan out at an angle from a compass bearing due northwest. On a sea chart, faint numbers indicating depth soundings warn of deep water, rocks, and shoals.]

demons assaulted our ships near these islands.

which were evaded.

but not without peril.

doubts assailed our sailors near these islands.

which were overcome.

but not without peril.

strange noises haunted our dreams near these islands.

which were drowned in sound.

but not without peril.

winds chased our sails near these islands

which were tamed.

but not without peril.

<JRC>

A Latin caption on the second oldest known printed map of the so-called new world, published by Johannes Ruysch in Rome in 1507, notes: Apud has insulas quando naute perveniunt illuduntur a demonibus ita ut sine periculo non evadunt (Demons assaulted ships near these islands, which were avoided, but not without peril) (Harrisse 1900, 58).

A contemporaneous commentary written by an Italian Celestine monk named Marcus Beneventanus suggests that Ruysch sailed on at least one voyage from the South of England. Some scholars have suggested he sailed with a Portuguese ship out of Bristol, on account of the number of Portuguese place names on his map. Others suggest he sailed with John Cabot in 1497 or 1498. I am inclined to favour the latter opinion for one reason: After his death, John Cabot’s son Sébastien Cabot published a mappemonde in 1544 which shows an island of Demons off Labrador.

There are no islands off Labrador.

None.

So where did this cartographic fiction come from? An Island of Sound does not set out to answer this question, but rather, to ask it over and over again, to imperil the quantifiable topology of imperial measure with an excess of possibility, cacophony, dissonance, and difference.

</JRC>

<JRA>

Acousmatic sounds, sounds whose source can’t be seen, cross the worlds of experience and imagination (Westerkamp 1999), and allow for transplanted, transformed sound collages that evoke the invisible and unspeakable.

In the sea mists off of the coast of Newfoundland, the sounds of unfamiliar seabirds, and the grunts and roars of sea mammals such as walrus, might have been very frightening, summoning visions of demons.

There’s a confusion of sound in this section. It’s difficult to distinguish individual elements, made stranger by the sound-bending effects of fog and the surface scattering effects of waves. The soundscape pulls back into an internalized sound perspective, filtering out the seabirds and introducing a hushed, resonant wind.

</JRA>

a film of dust

[Hushed, slow soundscape with sustained low volume drifting resonance and sparse, quiet, small, and short sound events that abstractly reflect the descriptions in the text.]

[Drawings of crystalline mineral forms are used throughout An Island of Sound to signal the close relation between wind-powered scientific colonialism and the ongoing exploitation of mineral resources.]

a film of dust

a curl of time

distant voices

frozen voices

a crust of frozen crystals

a sluggish tide

a breath suspended

a mess of feathers

a flap of ancient wings

<JRC>

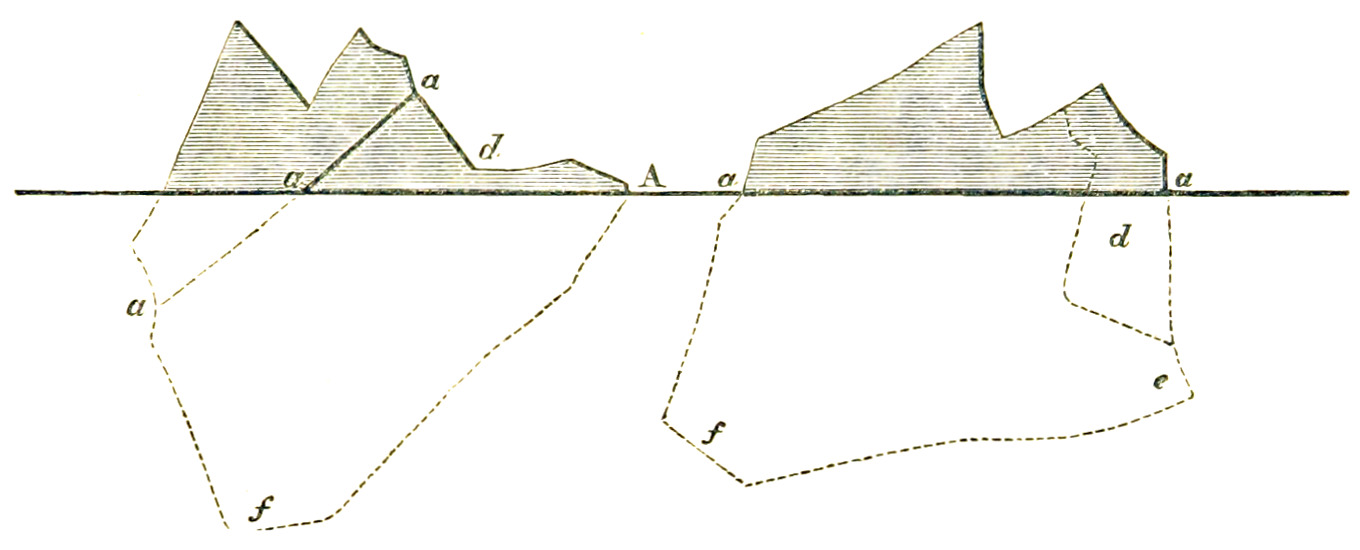

The topology of the phantom island continues its slow unfolding here. In a work no longer extant based on travels that may or may not have happened sometime between 330 BC and 320 BC, the Greek Pytheas described an island called Thule located six days’ journey north of Britain, and observed a strange phenomenon he called “sea-lung,” which was neither land nor sea nor vapor. In Agricola (AD 97–98), the Roman Tacitus notes a sighting of Thule, and that “the sea is sluggish and heavy to the oar” (Tacitus 1960, 60). In Pantagruel, Quart livre, chapter 55, the sixteenth-century French satirist François Rabelais writes of frozen voices (paroles gelées) at the edge of a frozen sea. His contemporary André Thevet accused him of satirizing his accounts of voices emanating from the Island of Demons. Campbell suggests Rabelais may have borrowed from earlier texts (Guillaume Postel, De orbis concordia [1543], or the fourth-century Neoplatonist Iamblichus), and credits him with providing “the material/linguistic traces of vividly absent natives” from Thevet’s accounts (Campbell 1999, 36).

</JRC>

crystal

[The hush is ongoing in the soundscape, the voice lightly processed to reinforce the looping repetitions of the text.]

bright. cold. clear. crystal.

wind. wind. wind. wind. wind. [loop]

alters. becomes. buries.

swallows. swallows. swallows. swallows.

the ancient. dry. brittle.

silent. silent. silent. silent. silent.

morning. coast. past. island.

world. world. world. world. world.

<JRC>

Through recurring mineral imagery, deep time enters the work, and runs concurrent to other times and temporalities already in motion: a seasonal cold, a morning bright, an annual migration. The swallows from the overture take flight again. The wind rises again, shifting in scale from the local to the global.

</JRC>

you want (an aria)

[Soundscape is almost silent. A sustained clarinet appears at the threshold of perception, growing into a morphing and wavering orchestral swell.]

[Visuals pan slowly and unevenly over illustrations of crystals, insects, and hemispheric projections, made abstract by the action of zooming in and out using the keyboard commands.]

<JRC>

If this is a libretto, then “you want” is its aria. A long song accompanying a solo voice, the word “aria” comes from the Italian word for air. This aria is elemental, dispersed between the web server and the client-side browser, the source code and the screen, the printed libretto and the speaking body, the microphone and the speakers, the room, and the bodies in it. The subject position has shifted, away from the lyric “I” of “I am not an island” to something multidirectional and diffuse.

</JRC>

ice.introduce_plug('youwant', new SwitcherPlug([

'something to change and nothing changes',

'something to happen and nothing happens',

'something to do and you do nothing',

'dry land under you and a ship comes for you',

'to leave dry land and no ship comes for you',

'dry clothing and all your clothes are soaking',

'sun to dry your clothes and it is still winter',

'sun on your face and the sun blinds you',

'sun on your skin and the sun burns you',

'wind in your hair and the air stills',

'wind in your sails and your sails hang slack',

'wind and the wind roars around you',

'a language and the wind speaks to you',

'a new language and you find you have no language',

'an absence of language to be of no hinderance',

'to be heard and no one hears you',

'to be seen and no one sees you',

'to swim and the water is frozen',

'adventure and you are transfixed by terror',

'security and the ground opens up beneath you',

'security and you are imprisoned',

'touch and there is only the bathwater',

'touch and there is only the duvet',

'touch and the wind touches you',

'time and time goes on for ever',

'space and space opens out before you',

'solitude and solitude engulfs you',

'silence and silence descends upon you',

'silence and strange noises assail you',

'silence and you are drowned in sound',

'sleep and cold seeps into you',

'sleep and cold keeps you from sleeping',

'sleep and cold creeps into your dreams',

'to eat and you become a bear',

'to survive and you become a bear',

'to walk and a bear walks with you',

'warmth and a fire burns within you',

'joy and you go searching for joy',

'joy and joy finds you' ]));

<JRA>

A slow orchestral swell sounds the sun rising and burning off the sea mists. A clarinetist turns breath into wind. As other instruments, horns and strings, join and tune to the clarinet, a range of other forms of wind layers are introduced, moving at different speeds in different registers (heights) and with different characteristics of stability.

The first additional layer is pitched wind synthesis with subtle instabilities in the generally sustained tone. The next layer to be introduced is made up of a field recording of wind across an open landscape. This is more turbulent in character, with pronounced whipping transients and transitions.

Another tuned wind sound is introduced, the amplified resonance of wind in wires, with occasional small impacts. The final layer is musical, short harmonic cello gestures, where the bow quickly moves across the strings as a gust of wind might blow across fence wires or cause a hanging object to push forwards and swing back, musical gesture and colonial remnant and reminder.

As with the textual array of words, this sonic element uses an array of samples chosen at random to produce a repeating yet varied musical form with the gestural “energy-motion trajectory” (Smalley 1997) of wind sway.

With the words “to eat and you become a bear,” the spoken word is transformed by extreme pitch-shifting, creating low register animalistic sounds. These sounds are throaty expulsions of air as grunts, growls, and blows, utterances and expressions of survival in challenging conditions, positioning the more-than-human elements of the work.

</JRA>

bears

[Soundscape fades to field recordings of bears vocalizing with some audible seabird cries.]

[Visual jump to an image of the head and neck of a polar bear, teeth bared, possibly dead. The hard left edge of the image, indicating the edge of a page, and the halftone reprographic technique, which breaks up the image into a series of dots to simulate the full tonal range of a photograph, situates this image within print book culture.]

four bears she saw

it was two bears, I say

three bears she sighted

it was four bears, I tell you

few bears she counted

it was two bears, I believe

two bears she passed

it was two bears, I remember now

one bear

white as an egg

<JRC>

The lyric “I” returns, but this time as fiction. In Glover’s Elle (2003), an unnamed first-person narrator based on Marguerite struggles to correct the author of her tale. The author, F. (François Rabelais), writes of “the girl who colonized the New World, killed three bears, and dwelt a year on an island inhabited by shrieking demons, where her words froze in the air as soon as they were spoken” (Glover 2003, 181). Elle replies: “Two, I say. Two bears died. I didn’t kill either of them. And the demons turned out to be seabirds” (181). Even as she corrects him, she contradicts a statement made earlier in the book, when she was still on the island: “The wind screams like a hundred hundred demons, far worse than the screaming of the birds” (65). In bpNichol’s poem “Lament,” it is the wind rather than the seabirds that lends the island its demonic moniker: “… the isle of demons / so called because the wind howled over the rocks” (Nichol 1985).

</JRC>

white

[Bears fade out as historical wind data sonification enters the soundscape.]

[Zooming out reveals that the halftone polar bear clutches a high-resolution branch in its teeth, under a black and white diagram of a constellation of stars labelled “Great Bear.” The branch, bearing bright red fruits and lush green leaves, is surrounded by illustrations of eggs.]

what is this white bear.

skin. sky. coast.

this white wash. white lie.

this wide white world.

of which you sing.

dream. do tell.

speak.

<JRC>

Thevet claims that Marguerite assured him that “on one day… she killed three bears, of which one was white as an egg” (Campbell 1999, 36). A polar bear is white as snow. This isn’t a question of literary affect. The polar bear’s survival depends on being literally as white as snow. A white egg enters into polar bear territory lodged in the colonial imaginary and hatches on the page. The digital archive presents an excess of eggs, collected under the auspices of scientific colonialism. The fictional “I” quibbles over numbers. The informational “I” surrounds the affective statement with twenty-nine eggs of varying sizes, shapes, and colours.

</JRC>

green

[The soundscape focus in this closing section is on sonification of historical wind data from Ron Galet’s Bay, Quirpon Island, off the northeastern tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula, one of the possible locations of the Island of Demons depicted on early maps.]

asking. dying. looking. longing.

for a breath. glimpse. glimmer.

of colour. of comfort.

of green. breeze. wind.

<JRC>

An AI trained on the British Library Flickr Commons might make visual correlations between a large illustration of a small green crystal and a small black and white line drawing of a large iceberg. A Mechanical Turk curator might tag these images #science. In An Island of Sound, juxtaposition disorganises these same-seeking principles, leaning into “the uncertainty of radical difference” (Robinson 2020). Ice is difficult, dangerous; green is living, breathing, and thus desirous. The human desires enumerated in the aria “you want” (touch, to be heard) implode into outright longing here, on a more-than-human planetary scale.

</JRC>

<JRA>

Sonification of climate data provides another opportunity to engage with the environment through listening. The aesthetic character of data to sound mappings can affect and make meaning. Andrea Polli (2004) has written “data interpreted as sound has the potential to communicate emotional content or feeling,” to convey information through auditory sensation. Her collaboration with Joe Gilmore, N. (2007), is an example of sonification of Arctic weather data that effectively portrays the harsh environmental conditions of this region through stark clusters of sine waves and noise.

In An Island of Sound, sonification of historical wind data is used to underscore the text’s narrative in supportive and reflective ways. Data is used in similar ways in Michael Begg’s Witness 2: The Weather Engine (Begg 2020), part of a series of works that aim to give voice to “solastalgia,” the emotional distress of living through environmental change (Albrecht et al. 2007).

Hourly snapshots of wind speed, direction, and atmospheric pressure set the relative pitches, amplitudes, and stereo positions of an array of simple sine wave oscillators and tuned noise filters to produce slowly shifting clusters of microtonal harmonic resonance. Where the daily data points are close together in value, the oscillator bank clusters tightly together, narrowing the soundfield, and where there’s more variation in readings, the sounding output is more broadband. This might also be seen then as an “aria,” a singing of air.

A slow offset is applied so that the overall movement appears to ascend and fade from the surface towards the sky, which, combined with quiet, intimate spoken word, creates a haunting, evocative ending for the performance.

This section is a zooming out of sound, moving from the discernible crack, creak, and fracture of ice, short events in spatial focus, to consider longer temporal forms and global patterns of a scale far beyond the scope of the work’s speculative hybrid soundscapes.

</JRA>

coda

[A black and white line drawing of twenty-five different types of snowflakes.]

and swallows on the wind.

and breathe.

and swallows in my lungs.

and breathe

<JRC>

Zooming in on this image disrupts its taxonomic logic. Its visual proximity to the much smaller image of icebergs dislodges assumptive relations to scale. It quickly becomes impossible for the viewer to see all the snowflakes depicted, which calls the very notion of a taxonomy of snowflakes into question. Each individual snowflake becomes enormous, an island in a sea of white space. The effect is disorientating: an approximation of a whiteout, a track-pad-driven wind moving through a low-fi weather event. The subject position of the speaking voice, decentred over the course of the performance, is now dispersed into air.

Taken as a whole, the digital images archived in the British Library’s Flickr Commons are redolent with colonial affect. The process of selecting and digitally collaging individual images for use in An Island of Sound contributes to disrupting the deep-seated settler colonial narratives of phantom islands by decentralizing the visual tropes of devils, demons, Sirens, and white settler women. Instead, images from the more-than-human worlds of plants, animals, minerals, wind, ice, and snow have been entered into discourse. The digital collage of these images operates outside any formal apparatus of citation, displacing the displacers and renaming the renamed. The overt plundering and pillaging of the digital archive calls attention to the colonial acts by which this archive was constituted—acts of taking, renaming, reordering, and representing contents out of context. The subject is thus reconstituted as more-than-human—island, ocean, ice, snow, wind.

An Island of Sound charts multiple shifts in association, amplifying rather than clarifying confusions and conflations between islands (real and imagined), soundings (audible and measuring), voices (human or otherwise), and bodies (of birds, women, and water). It does so by thinking through and with wind as an elemental media, connecting elements across time and space.

Swallows are evoked in the overture for their associations with radical migration, circumnavigation, sailors, and wind-powered sailing ships. They are man-made marks: woodblock printed, inked into skin. Swallows are evoked again in the coda. Firstly, as actual birds, in actual wind. And secondly, as bodily actions: the act of swallowing, a final intermingling of wings, wind, body, breath, and air.

</JRC>