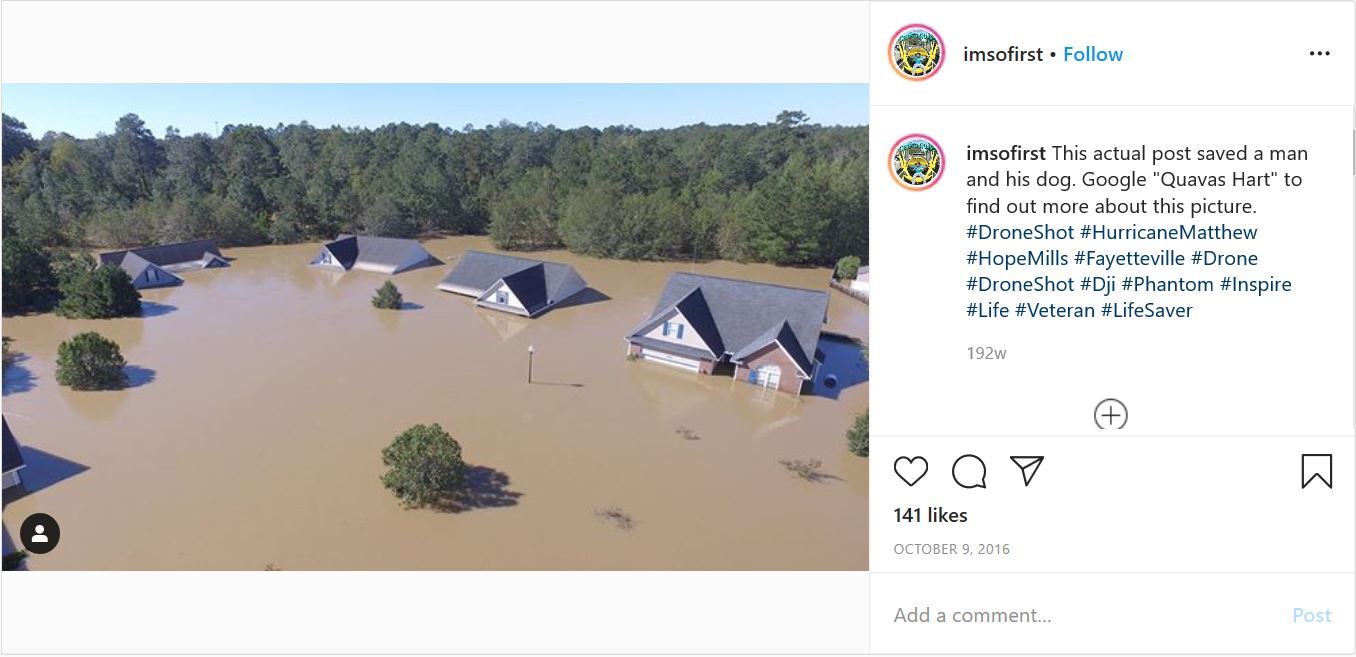

“Drone, Social Media Make Flood Rescue Happen in Real Time,” ran the headline of a US news item published in October 2016 (Ellis and Newsome 2016). According to the story, a man named Quavas Hart, of Fayetteville, North Carolina, flew his consumer drone over homes engulfed by floodwaters in nearby Hope Springs in order to take aerial photographs (figure 1).

Hart then uploaded the images to Instagram and shortly thereafter was contacted on Twitter by a stranger in Texas named Craig Williams (figure 2). “Holy s**t that’s my brothers [sic] house… the one with one shutter. Any chance you can boat him out of there? He’s trapped upstairs,” read Williams’s urgent message (Ellis and Newsome 2016). As it turned out, Williams’s brother, Chris, had been stranded in his attic for fourteen hours, and Hart’s Instagram photo was the first time he saw the imminent danger his brother was in. Despite repeated efforts to contact government agencies to rescue Chris, no one picked up Craig’s calls. As he remembered it, “We called local emergency services, we called the fire department, and nothing would go through” (Ellis and Newsome 2016). So Craig Williams appealed directly to Hart, who used his drone to attract the attention of a passing Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) crew, guiding their boat to Chris’s home. According to Hart, “They wouldn’t have checked that house had I not distracted them with my drone” (Ellis and Newsome 2016).

Summed up as a story of “a drone operator, the perseverance of family and the cross-country reach of social media” (Ellis and Newsome 2016), this news story about a rescue in the wake of Hurricane Matthew underscores the humanitarian potential of putting new media technologies in the hands of private citizens in times of environmental disaster. What makes the tale of Chris’s rescue from the attic particularly interesting, however, is not only that it casts citizen drone rescue in heroic terms but also that it naturalizes and anticipates the outsourcing of disaster relief to private actors. In dwelling on the saga of missed connections and sheer coincidences that the rescue depends upon, the news story highlights the absence of reliable public emergency services at the same time as it promulgates the promise of a spontaneous media network of care linking strangers via consumer electronics and social media corporations operating on national scales. Quavas Hart’s quick thinking with his personal drone suggests that citizens can commandeer media assemblages to assume the work of public welfare in times of peril, effectively transforming into privatized agents of postdisaster search-and-rescue missions in the process.

Of course, discourses that cast the figure of the private drone operator—and the capacities of high-tech media—in heroic terms belie the complexities of disaster rescue work and its uneven availability across private and public sectors. This reality is, in part, a result of the state’s dramatic reductions in public expenditure in an age of intensifying neoliberalism. Defunding has had profound consequences for disaster management in climate emergencies. In the aftermath of Hurricane Matthew, for instance, North Carolina officials learned that many of FEMA’s maps of federally designated flood zones were out of date (Wagner 2020). As a result, thousands of homes were built in floodplains while their owners lacked flood insurance. As Julie Wilson reminds us, reduced public spending is fundamentally interventionist; it aims to transfer the distribution of social welfare to the free market (2018, 37). Wilson’s point underscores that, under disaster conditions, the defunding of those state agencies that provide emergency relief cannot be explained away as an unfortunate by-product of government neglect. The reduction of emergency aid is a deliberate political gambit on the parts of particular states or particular federal administrations, argues Wilson—one calculated to gut public funding and reassign resource allocation to the market in times of crisis. The complex configuration of public and private responses to environmental disasters in the context of twenty-first-century neoliberalism has entailed nothing less than a wholesale reconfiguration among citizenship, security, and the state. As a result, “more and more of the population has been enlisted for humanitarian work…[while] poor women, children, people of color, and immigrants find it increasingly difficult to access their rights (not just to welfare but also to proper wages and protections)” (Grewal 2017, 14).

While the twinned rise of state neoliberalism and privatized humanitarianism has meant the dissolution of social securities for millions of disenfranchised American citizens and residents, the nation’s mainstream media has tended to occlude this development, particularly in cases of post–environmental disaster reporting. Writing of the humanitarian crisis that unfolded after Hurricane Katrina, for example, Inderpal Grewal observes that journalists frequently framed the domestic policy disaster as a regrettable geopolitical gaffe that tarnished the United States’ international reputation rather than as a culmination of “the effects of poverty, racism, and the lack of infrastructure to shore up the levees” (2017, 40). Given the failure of the mainstream media to acknowledge these transformations to state security, we must first question the dominance of flood rescue narratives that highlight the heroic drone operator as a humanitarian figure. This work builds on the point made in Kristin Bergtora Sandvik and Maria Gabrielsen Jumbert’s edited collection, The Good Drone (2017), that new discursive formations have built up around the beneficial uses of drones for civilian purposes in territories such as “the humanitarian emergency zone” (2). Second, we must critique the cultural implications of discourse that situates the humanitarian figure of the drone operator alongside the outsourcing of disaster relief while bearing in mind that media texts are complex. In the news story with which I began this article, the drone operator did not effect the rescue on his own but rather used the drone to summon federally dispatched first responders. Indeed, from Hurricane Katrina to Hurricane Matthew, public emergency rescue services have regularly operated in conjunction with private drone operators. However, while this particular flood rescue story evinces an improvised collaboration between Good Samaritans and FEMA in the performance of the attic rescue, its dominant narrative gravitates to the former even as the structural relationships under discussion still pertain.

In addition to an analysis concentrated on the discourses of disaster response, this article also undertakes an examination of the consumer eco-drone as a technological and infrastructural assemblage. Recently, scholars in the field of media and communication studies have called for heightened critical awareness of the complex materialities of the media infrastructures that distribute digital content and determine its form (Parks and Starosielski 2015, 1). Adopting “an infrastructural disposition” shifts the focus of media studies to the histories and processes of signal distribution, the materialities of that distribution, and the public’s technological knowledge of these infrastructural matters (Parks and Starosielski 2015, 5). This allows for a reassessment of the ways “that industries and people imagine, organize, and use those infrastructures, and the varied scales at which they operate” (Parks and Starosielski 2015, 1). Significant to the context of flooding, Parks and Starosielski point out that media infrastructures are “inseparable from the biophysical environment” (2015, 14).

In what follows, I use textual and infrastructural analysis to study the relational movements of and discourses about networked agents. Specifically, by recasting amateur environmental disaster images uploaded to social media platforms as citizen ecosensing, we can effectively cleave apart the conventional linkage environmental media scholars make between the speed at which new technology senses flooding disasters and the efficiency with which such disasters are managed. The cases of rural flooding I examine in this essay quite often reveal the marked discrepancy between the quickness with which environmental disasters are “sensed” and the slowness with which they are responded to. Under analysis, these cases also reveal how a lack of private wealth in these rural communities makes the absence of state resources more pronounced. This concentration on citizen ecosensing from the drone’s aerial position also can contribute to revelations about physical infrastructures such as roadways, communications networks, or hydrological engineering along the Gulf Coast. Considering the use of privately owned consumer drones from this perspective, I seek to demonstrate that alongside the reduction of government resources and the rise of informal sensing and rescue networks comes what I call humanitarian drone discourse. Instead of regarding this as a cultural manifestation particular to the climate crisis experienced on US soil, this article accepts that humanitarian drone discourse is itself an imperial formation. For in addition to the official policies that facilitate the United States’ drone wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, and elsewhere, militarized drone attacks are also set in motion through the biopolitical discourses that have cast the drone as a humanitarian technology that not only takes life but also protects it. To take drones seriously as “biopolitical machines,” as Lisa Parks and Caren Kaplan have called them (2017, 10), is to come to terms with the vitalizing element that courses through the cultural imaginary of the drone as it is deployed across a range of theaters. Attending to this cultural imaginary will link together the discourses that frame the disaster rescuer’s unmanned aerial systems that are designed to rescue the lives of those trapped by floodwaters and the wildlife conservationist’s unmanned aerial systems that are designed to preserve the lives of animals to the military’s unmanned aerial system designed to protect the lives of citizens and residents of the United States. Whereas drones are touted by the mainstream media and the drone industry as a consumer technology with humanitarian (and humane-itarian) capabilities, I will analyze how cultural narratives often present the deployment of eco-drones as a life-giving operation of US biopolitics although the reality is more complex.[1]

Citizen Ecosensing

In the wake of natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, and fires, social media platforms are awash with amateur photos and videos that bring the immediacy of local devastation to millions of viewers across the globe. We can classify the capture and circulation of such images as ecological surveillance or “ecosensing” by private citizens insofar as this labor offers a nonprofessional but nonetheless near instantaneous visual record of environmental catastrophe. Facilitated by consumer electronics such as cell phones and consumer drones, the practice of citizen ecosensing approximates professional methods of documentation taken up by corporations, scientific bodies, and government agencies in recent years. For advocates of ecological surveillance, professional forms of ecosensing promise to ensconce the planet within an expanding cybernetic web of instrumentation, effectively reimagining the earth as a self-reporting patient that communicates its injuries and facilitates its healing through human and nonhuman corrective measures. In Program Earth, environmental media scholar Jennifer Gabrys describes such surveillance practices as the “sensorization of the environment” (2016, 4); that is, the deployment of remote sensing technologies in the service of environmental monitoring—“a practice that is computational, often networked, frequently automated, and increasingly ubiquitous” (2016, 3). These practices can include putting to work any number of sensing technologies, be they terrestrial, aerial, or both. Satellites, for example, regularly relay atmospheric and visual information back to earth, operating as the “eye in the sky” for networked digital infrastructures recruited to track environmental conditions remotely (Gabrys 2016, 3).

More recently, ecologists and conservation biologists have expanded their aerial environmental sensing resources by bringing unmanned aerial systems (UAS), or drones, into the fold of digital sensing technologies (Anderson and Gaston 2013; Zhang et al. 2016; Koh and Wich 2012). With their unique mobility, “eco-drones” (2016, 60), as Gabrys calls them, work alongside satellites and conventional static web cameras, “as yet another camera-based mode of sensing […]” the environment (2016, 60–61). The drone’s sensing capacities come to the fore, for example, in reports recounting the adoption of the eco-drone as a lifesaving instrument intervening in the environmental crisis of species extinction. The recruitment of this technology in animal conservation efforts is evidenced in the sheer number of global scientific projects that deploy these aerial systems. Within the United States, for example, eco-drones are tasked with rehabilitating the precarious lives of endangered species such as the pygmy rabbit by monitoring its disappearing sagebrush habitat in the desert between Shoshone and Hailey, Idaho (“Pygmy” 2011), while outside the United States, the eco-drone guards the lives of charismatic megafauna; in the Liwonde National Park in Malawi, for instance, trained operators deploy thermal cameras affixed to Bat Hawk drones to spot potential poachers who hunt protected elephants and rhinoceros (Nuwer 2017). The eco-drone also has revolutionized the process of visually monitoring the dynamic environmental conditions characteristic of natural disasters. Whether flying over melting ice sheets in Greenland (Turrin 2018), monitoring lava flow from the Kīlauea volcano in Hawaii (U.S. Department of Interior 2018), or capturing infrared imagery of active wildfires in Australia (Allison et al. 2016, 12), the eco-drone’s ability to traverse the planet’s most inhospitable environments has ushered in unprecedented perspectives on the nonhuman world and, in doing so, has shaped the way we visualize environmental change in the twenty-first century.

Proponents of the turn to aerial sensing technologies predict that the drive to survey all aspects of the environment—the complete “instrumentation of the planet” (Gabrys 2016, 7)—will not only transform the public’s environmental imagination but also hasten the mobilization of humanitarian aid in future environmental disasters (McFarland 2015; Gross 1999). In the case of humanitarian crises precipitated by floods, for example, Gabrys states that planetary self-reporting could proceed through sensors “used to […] signal flooding alerts, and to enable rapid responses in disaster situations” (2016, 7). This means “floods can be instantly reported to ensure intelligent and immediate environmental management” (Gabrys 2016, 8).

Yet the claim that the near instantaneous speed at which information travels through digital networks will inevitably lead to similarly “rapid” or “immediate environmental management” deserves careful scrutiny, especially given that it elides the discrepancy between disaster reporting and disaster management. Just as the opening story illustrated that the heroic drone operator’s promise of help did not entail immediate rescue, so too does the case of high-tech ecosensing reveal a sharp discrepancy between the fact of sensing and the amelioration of environmental disasters. This point is brought home in the next section, which discusses cases where, despite readily available consumer sensing equipment that allows for an aerial view and for flood conditions to be reported nearly instantaneously, widespread disaster ensues. In what follows, citizen ecosensing by consumer drone does not lead to the rapid deployment of public resources. In fact, as a rejoinder to the lifesaving discourse of the heroic drone operator, citizen ecosensing from above does not apprehend an authoritative view that unifies the sights below; instead, it documents widespread infrastructural failure and the devastation caused by the absence of public welfare in times of ecological disaster.[2]

Infrastructural Breakdown from Above

The mediation of catastrophic flooding in the southern United States has a long history. The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was one of the twentieth century’s earliest environmental disasters to be “experienced on a mass scale” (3) thanks to the various forms of representation across media such as radio, newspapers, theater, blues songs, and novels (Parrish 2017). In the twenty-first century, media studies scholars including Diane Negra, Henry Giroux, and Pooja Rangan have addressed the mediation of the catastrophic flooding that followed Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (Giroux 2006; Negra 2010; Rangan 2017). Today, still and moving aerial images of flooding posted by private individuals have become something of an emergent genre on social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. For example, in the case of the floods in the southern United States in 2016, anyone with access to the internet could access the flood images by searching hashtags such as #louisianaflood2016 or #flood2016. Within this digital media milieu, YouTube user and drone operator Dev/Null successfully transmitted images of catastrophic local flooding to the world via video uploaded to YouTube. Over several consecutive days in August 2016, Dev/Null became an ecosensing citizen-subject when they shot a series of amateur videos with a consumer drone that captured aerial footage of the catastrophic flooding in and around Livingston Parish, east of Baton Rouge, near the cities of Denham Springs and Springfield.

As the New York Times reported, the Red Cross regarded the “deadly off-the chart deluges and flooding” in this region as the “worst natural disaster” on US soil since Hurricane Sandy in 2012 (Revkin 2016). According to another report, the torrential rainfall recorded in Louisiana that August “matche[d] or exceed[ed]” the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) “predictions for amount of precipitation that will occur once every five hundred years or has a chance of occurring in any given year” (Bromwich 2016). What is more, this was the eighth such weather event in the United States to defy NOAA’s predictive model in the span of just sixteen months. The thirty-one inches of rain that fell on Louisiana “exceeds an amount of precipitation that [NOAA] predicts will occur once every thousand years in the area” based on models of a stable climate (Bromwich 2016). Meteorologists and climate analysts attributed the massive storm system that brought the rains to Livingston Parish to unseasonably high temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico, coupled with the warm waters of Louisiana’s shallow swamplands (Revkin 2016). Without adequate drainage across the region, severe flooding ensued. FEMA declared twenty-one parishes in the state as federal disaster areas (Revkin 2016). Thirteen people drowned. Twenty thousand citizens required rescuing. Thousands more were displaced from their homes, and “[t]ens of thousands of homes and businesses [were] swamped” (Bishara 2016; Revkin 2016).

Given the lack of national news footage showing the devastation experienced by the people who lived in Livingston Parish, Dev/Null’s videos provided important visual evidence of the unprecedented flooding experienced in rural Louisiana to thousands of viewers on YouTube’s video-sharing platform. Dev/Null’s uploaded videos also communicated more than the changing water levels. Thanks to the drone’s elevation and the parish’s flat, rural landscape, the videos also visualize the collapse of terrestrial transportation and communication networks at an infrastructural scale. One of the videos dwells on spaces once occupied by automobiles. In it, the drone hovers low, documenting a submerged parking lot and strip mall located at Route 12 and Jublan (Dev/Null 2016a). Moving across the parking lot, the mobile camera pans slowly over the water’s surface. As it makes its solitary rounds, the shop names on the storefronts are easily legible: Rouses Market, Ulta, Bed Bath & Beyond, Ross Dress For Less, Shoe Carnival, PetSmart, Lane Bryant, and Movie Tavern (figure 3).

Piles of sandbags block store entrances in an effort to keep out the rising water. Parked trucks are scattered along the water’s edge. The drone’s exploration of the mall not only monitors the flood’s progress but also evinces the ease with which the aerial camera navigates Route 12’s newly aquatic environs, a feat impossible for vehicles confined to terrestrial modes of locomotion. The contrast between the presence of the drone and the absence of automobiles is pronounced. Indeed, the uncanny appearance of the abandoned American strip mall offers a stark visual reminder of late capitalism’s continued dependence on land-based transportation infrastructures to bring both goods and customers into brick-and-mortar stores. Dev/Null’s video thus documents the fragility of the local system of roadways that rural southerners depend on to reach goods and services. A change in weather patterns leaves the highway system suddenly fragmented; the area’s existing transportation infrastructure cannot function without dry land.

In another video posted a day before, entitled “Louisiana Flood 2016—Springfield Hwy 22” (Dev/Null 2016b), trapped vehicles litter the landscape once again. From the drone’s vantage, the muddy floodwaters transform the once uninterrupted expanse of farmlands and rural homes into a temporary archipelago. Surrounded by water, parked yellow buses are immobilized, confined to their schoolyards. Five pixelated human shapes, a black pickup truck, and a boat trailer occupy another island of land (figure 4).

Nearby, a spidering pattern of brown water marks out where roads once led. Dev/Null’s drone rises and loosely tracks a broad expanse of water through the trees. Here, the tops of telephone poles peeking out of the water at intermittent intervals nearby are the only visible indication that this was once a highway. But the repetition of the poles punctuating the aquatic landscape in this moving image also testifies to the materiality of Livingston Parish’s existing terrestrial communication systems under siege. The wires necessary to transmit electricity and telephone calls dip low under the extreme environmental stress.

The eco-drone thus provides a unique perspective: precisely because it does not rely on either telephone wires or roadways to connect to the world beyond the parish, it can transmit scenes of ruptured communication and transportation networks through media infrastructures of its own. Dev/Null’s eco-drone functions as one component of a transhuman media infrastructure in this instance—a material formation that comprises both human and nonhuman agents, including the drone’s operator, camera, and rotors, as well as computer, internet cables, servers, atmosphere, and floodwaters—that enables the circulation of ecological information at local, national, and global levels. The contrast between this network and Livingston Parish’s inundated local and national terrestrial networks is a stark one. Because so many components of traditional infrastructures remain bound to the earth and exposed to the elements, such networks are especially vulnerable to environmental disasters—a vulnerability compounded by government mismanagement. Moreover, the failure to link up citizen eco-sensing through private networks with public search and rescue resources not only underscores the lack of government aid in such situations, it also highlights the absence of forms of heroic rescue from the private sphere as well.

Drone Humanitarianism

By conceptualizing the consumer eco-drone as an element in a vast media infrastructure, the improvisational transhuman agencies it mobilizes in the wake of disaster come into view. This framing positions the figures of the postdisaster eco-drone and its pilot not as maverick private agents of disaster relief but rather as indices of the failed public infrastructure of the neoliberal state. And yet, as the news report with which this essay began illustrates, stories of postdisaster flooding tout the privatized humanitarian drone as an indispensible instrument for the industrious citizen who flies it into action. The privatization of citizen rescues in the aftermath of disaster has given rise to the emergent figure of the heroic drone operator. This recreational flyer’s combination of privately honed piloting skill and humanitarian impulse is conscripted as a form of flexible work volunteered on behalf of the public good in times of ecological crisis.

Consumer drone rescues constitute just the latest iteration of a long-standing practice of emergency assistance via private recreation vehicle in the aftermath of natural disasters. For instance, after Hurricane Katrina, stories of rescue by exceptional citizens outfitted with pickup trucks and fishing boats became a regular feature in disaster reporting. National media coverage of the flooding in and around Houston, Texas, after Hurricane Harvey in 2017 also drew attention to the prominence of volunteer rescue efforts by private citizens. The stories that circulated about the “Cajun Navy”—described as a “volunteer online grass-roots effort” (Wax-Thibodeaux 2017) that is “founded on the realization that large government agencies aren’t quick-moving” (Jenkins 2017)—were particularly quick to expound on the phenomenon of crossing state lines to selflessly help fellow citizens in danger. In one of these stories of private rescue, the work of the Cajun Navy is framed through the eyes of Jordan Bloodworth, a young member of the group and a survivor of Hurricane Katrina. According to the report, Bloodworth lost all of his material possessions in Katrina but “gained…a deep motivation to help his brethren in Texas” when Harvey struck (Wax-Thibodeaux 2017). “I was young during Katrina and I know how it feels to lose everything,” he explains. “So being able to help others going through this situation that I have experienced, there’s no way—no way—I could pass up helping” (Wax-Thibodeaux 2017). In Bloodworth’s account, the brotherhood of interstate survivors is forged through the shared experience of dispossession. While some rescue volunteers framed the labor of private disaster rescue as a means of shoring up an extended family, others narrated these selfless acts as mainstays of Cajun cultural identity. For example, another member proposed that his compulsion to rescue strangers could be explained by his Southern upbringing: “it’s just the way we were brought up… you help your neighbor” (Wax-Thibodeaux 2017). In this observation, private rescuers downplay the heroism of their actions at the same time as they naturalize the humanitarian desire to rescue others.

As with fishing vessels commandeered by the Cajun Navy, consumer drones—the latest iteration of rescue vehicle—similarly convert the recreational play afforded to private citizens into socially beneficial skills to be volunteered during disasters. Like the Cajun Navy members, drone operators express a communal desire to provide assistance to those trapped in emergency situations even as the state supplied support from the skies. Speaking in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, one pilot said: “I know there are airborne emergency operations going on in Houston as we speak, but I also know there is a whole community of [drone] operators ready to coordinate with local authorities to aid in whatever way they can” (Greenemeier 2017). These stories of public-private rescue configurations happen against a broader economic backdrop in which recreational practices have become increasingly indistinguishable from profitable enterprises. This blurring occurs in a story entitled “Drone Company Saving Lives in Louisiana Flood,” which observed that a “drone photography company located in Louisiana…posted a message on their Facebook page” offering to fly over and photograph the neighborhoods of unaccounted-for loved ones and was swiftly inundated by messages requesting assistance: “Desperate requests to check on buildings, animal shelters, senior communities, and cemeteries—where loose coffins have been seen floating down flooded streets—are being posted and responded to” (McNabb 2016).

The discursive character of this communal response expressed by private sector drone operators in these instances hearkens back to the masculine, white working-class narratives of self-reliance that have cropped up in other communities within the United States grappling with the problem of responding to unprecedented natural disasters. Writing of the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in the Rockaways, Jon Kraszewski points out that stories of “self-sufficiency and entrepreneurship are the keynotes of neoliberal response to extreme weather” in the United States and that “the way these traits became associated with nostalgia for a ‘simpler’ time in America allows tropes of self-reliance to function not as an anxiety-provoking response to contemporary problems but as a soothing recollection of yesteryear’s joys” (2015, 33). In much the same way, stories of disaster rescue in the South turn to the consumer drone not as a cutting-edge technology but as a new humanitarian tool with which to act out a familiar script of overcoming physical perils to achieve communal self-sufficiency in the face of mounting structural inequalities.

The tenacity with which these cultural narratives allot humanitarian agency to the eco-drone operator situates both the figure of the heroic drone operator and the drone itself firmly in the American public’s biopolitical imagination. At the same time, these narratives position drone operators as a supplement to the state. Discourse surrounding the eco-drone routinely positions this consumer technology as a mechanical agent tending to the biopolitical imperative to administer life—to advance what Foucault describes as the mandate “to foster life” or to make live (1990, 138).

The implications of bestowing life-giving qualities onto domestic drones given the broader geopolitical context of the late US empire’s reliance on lethal drone strikes are many: to address them, one must adopt a broader historical view of ecosensing drones via a media archaeological approach. In his account of “Earth-Observing Media,” communications scholar Chris Russill defines the “‘dual use’ conception of media technology” as “an industrial policy that acknowledges the formative influence of military design and funding on technology (radar, sonar, automated computation, satellites, etc.), while suggesting that civilian and peaceful applications are just as likely as not” (2013, 280). So while dual-use technology “carr[ies] humanitarian promises that open-source and real-time accessibility will generate social good from recording, storage, and processing capabilities,” Russill observes that these capabilities “remain as unevenly distributed as ever” (2013, 281). Caren Kaplan addresses the implications of this dualism, speaking with respect to the daily civilian use of geographic information systems (GIS): “for people in the United States war is not elsewhere but is, in fact, deeply imbricated in everyday life as a ‘military-industrial-media-entertainment network’” (2006, 694).[3] She contends that as the uncritical use of military-developed technologies saturates contemporary culture and becomes normalized, so too does the militarization of citizens and consumer subjects of the United States.

Kaplan’s argument has powerful implications when it comes to appraising the influence that consumer eco-drones wield as technologies discursively interwoven with the protection of life in times of environmental crisis. Such a view of unmanned aerial technology may be transposed into the arena of international warfare, where the lethal use of drones to carry out signature strikes and targeted killings has become emblematic of the US-led war on terror. As technologies of US imperial power, militarized drones consign untried individuals to death via the extralegal violence administered by the state’s self-assigned power to decide who dies. For political philosopher Achille Mbembe, the logic that would kill others in order to maintain the life of one’s own population describes the dark underbelly of Foucauldian biopower (2003). Such a necropolitics, as he calls it, is often regarded by state actors as an extension of the government’s promise to make its population live. In Théorie du drone, Grégoire Chamayou tracks the necropolitics of warfare that arise with the adoption of the remotely controlled weaponized drone. He observes that for “philosophers working within the confined field of military ethics,” the military drone has been conceived of as “the humanitarian weapon par excellence” (2015, 17). By eliminating the possibility that a military life will be lost in combat, proponents argue, the drone adheres to “the principle of vital self-preservation” (2015, 137). “[I]t is in accordance with this logic,” says Chamayou, “that the drone can be said to be a ‘humanitarian’ weapon: the humanitarian imperative is to save lives. And it does indeed save our lives. It is therefore a humanitarian technology” (2015, italics in original, 136).

Reread through a jointly infrastructural and discursive analytic, the discourse around the domestic eco-drone as an ostensibly humanitarian, life-giving technology may be seen as veiling its alignment with the geopolitical objectives of the US security state, which, “under the guise of war, of resistance, or of the fight against terror, makes the murder of its enemy its primary and absolute objective” (Mbembe 2003, 12). This latter imperial formation is visible in the many reports touting the consumer drone as a tool of humanitarianism in times of environmental crisis. But, in fact, the domestic rise of consumer drones for eco-sensing and humanitarian purposes cannot be disassociated from the violence of the drone-assisted war on terror that carries on abroad. “It would be mistaken to limit the question of weaponry solely to the sphere of external violence,” Chamayou writes at the close of his monograph’s introduction. “What would the consequences of becoming subjects of a drone-state be for the state’s own population?” (2015, 18). A regard for the life-giving properties associated with eco-drone humanitarianism that blinds us to the US military’s use of drones for necropolitical purposes is one response to his question.

By taking the cultural narratives of the domestic eco-drone seriously, the implications of the propensity to frame drones as humanitarian tools in times of environmental disaster come into view. Returning once again to the attic rescue with which this article opened, we can see that while the coordination of private citizens working in conjunction with FEMA proved crucial to its success, humanitarian drone discourse centers the figure of the heroic drone pilot above all else, effectively offloading the responsibility of saving lives from government agencies. Portrayed as resourceful and selfless private citizens who assume the responsibility of saving neighbors and strangers alike, recreational drone enthusiasts find themselves embodying the neoliberal privatization of humanitarianism in disaster conditions. To be sure, the extraordinary care work these citizens perform to save others is real; nonetheless, it is also the case that media portrayals of this care as masculine heroism deflect from a serious reckoning with the government’s responsibilities at the state and federal levels.

Even with these powerful cultural narratives, this analysis of the eco-drone assemblage has disclosed the inevitable structural disruptions that upset the fantasy of seamless private rescue: while ecosensing technologies may speed up the detection of people or animals in need of rescue, the arrival of on-the-ground emergency services still ultimately depends on government funding to facilitate the presence of rescuers and caregivers. Emergency responses can be especially difficult in flood conditions. Indeed, the citizen ecosensing of flood conditions also lays bare large-scale infrastructural problems, making visible a disordered landscape of unusable roadways and downed telecommunication networks in those communities devastated by floodwaters, and showing that rescue is not always readily at hand. The temporal discrepancy between the immediacy of ecosensing and the lag of emergency responsiveness in humanitarian disasters undermines the appeals to efficiency so often made by those who advocate for the widespread adoption of eco-drone technology. The analysis of humanitarian drone discourse and infrastructures laid out here makes clear that appeals to reframe the drone as a life-giving technology must continue to be carefully critiqued given the precarious lives—in the United States and abroad—that hang in the balance.

Author Note

Banner Image (HTML version only): Aerial image of flooding in Louisiana, Pixabay, Feb 16, 2013. Image by David Mark. Source: Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/photos/new-orleans-louisiana-81669/.

For an example of how the consumer drone industry touts the humanitarian applications of their technology, see “DJI Drones Saving the Day During Texas Flood Rescue” (2015). On the concept of “humane-itarianism” and the rescue of animal life, see Rangan (2017), particularly pages 151-190.

For a thorough discussion of the cultural history of the aerial perspective, and the tendency to regard this perspective as a means to legibility and control, see Kaplan (2018).

For more on the term “military-industrial-media-entertainment network” see Der Derian (2001).