At the end of 2018, we conceived of a thematic issue—or “stream,” in this journal’s parlance—to engage Media+Environment’s commitment to publishing research about media as variously representational, infrastructural, and elemental, yet always already environmental. “Disaster media,” as we call this stream, aims to analyze how media emerge and change shape during crisis situations and to cultivate attention to new modes of disaster relief and environmental justice.[1] Toward that end, we define disaster media as a heuristic, or approach, that recognizes the ways “natural” and human-made disasters are communicated about, constructed, and variously exacerbated or relieved through media means. This heuristic is not simply a temporary model for problem solving but tries to account for ecological forces and material conditions.

We write with awareness of media’s embeddedness in the overweening engines of modernity and, at the same time, with conviction that media can help reshape dire environmental, affective, and economic conditions. Our past studies have focused on the satellite imaging of war and human displacements in Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur (Fair and Parks 2001; Parks 2005, 2009) and documentaryS films featuring situated testimony by survivors of Hurricane Katrina and residents in areas of Louisiana’s Gulf Coast where increasing weather volatility, sea-level rise, and wetland loss are threatening long-established communities (Walker 2010, 2018). Alongside many other people, we have read about, and in one case experienced from nearby, devastating occurrences in different locales: massive fires in the state of California, in the Amazonian rainforest, and throughout parts of Australia; cyclones, typhoons, and hurricanes in Mozambique, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico; and oil spills by Nornickel in Russia, by Compañia de Acero del Pacífico in Chile, and by TransCanada Corporation in the United States.

As media scholars working in the United States concerned about the global impacts of climate disruption,[2] we have tracked the ways sociopolitical systems and media cultures are confronting, ignoring, or perpetuating this crisis. In what follows, we discuss mainly conditions in the United States yet invoke and learn from examples in other countries. Witnessing and voicing our objections to US federal fossil fuel subsidies, withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, suspension of environmental regulations, and lack of congressional momentum toward a Green New Deal, we realize that the United States is a major perpetrator of climate disruption. And we recognize climate disruption as a disaster that threatens to end all human disasters, one of huge proportions, complicated linkages, and already ongoing despoliation and suffering.

The word disaster, meaning dis + astro, or star (from the French, Occitan, or Italian)—or, in the adjective form, “ill-starred” (Oxford English Dictionary online)—has an astrological connotation as “a calamity blamed on an unfavorable position of the planet” (Etymonline). Disasters like those mentioned above are often thought—or argued—to be “acts of God,” “natural disasters,” or force majeure. However, to come down to earth, it is our conviction that it is not “the stars”—or even “humans” collectively—that are to blame for the unmitigated disasters that living beings, including people and all other life-forms, are being subjected to, but rather heavy industry leaders and political supporters of “disaster capitalism” (Klein 2007, 2014; Malm 2015), which is necessarily racialized capitalism (Robinson 1983; Gilmore 2007; Yusoff 2018). We embrace the social ecological principle that “[a]lthough many ‘natural’ disasters are caused by the shifting of tectonic plates or by the interactions of bodies of water with atmospheric conditions, they are not separable from the consequences of human actions” (emphasis added) and the grim corollary that those who are already disadvantaged often suffer more when disaster strikes (Fothergill, Maestas, and Darlington 1999; Park and Miller 2006, 10; Bullard and Wright 2012; Finney 2014; Pellow 2018, 6; Rodrígues, Donner, and Trainor 2018). Therefore, in thinking about disaster media, scholars must grapple with complex ecological, social, and economic relations and work toward salient solutions. Efforts to institute safety regulations, emergency rescue protocols, private-sector response teams, and insurance instruments as protection against losses of life, limb, and property might seem appealing in a “risk society” (Beck 1992). Yet as researchers have demonstrated (Siegel 2014; Uncertain Commons 2013; Ghosh and Sarkar 2020), the intensely mediated management of accidents also cultivates risk as a salable product that will never satisfy—and depends on never satisfying—the genuine needs produced by climate disruption as “the inevitable downside of progress” (Beck 2009, 25; Nelson and Walker 2020).

As with resisting blaming celestial bodies, human nature, or “accidents” of various types and sizes, we distance ourselves from the litany of media reports that spectacularize catastrophic occurrence and place the onus for testimony, resilience, and survival on affected people and communities (Nixon 2011; Kraszewski 2015). We are committed to the wisdom of Rob Nixon’s call to attend to “slow violence” or “[t]the long dyings—the staggeringly discounted casualties both human and ecological that result from war’s aftermaths or climate change” (2011, 2–3). And we are compelled by Amanda Lynch’s and Siri Veland’s reframing of the Anthropocene narrative away from one of extremes and emergencies and toward human dignity and sustainable coexistence with earth systems (2018). With these cautionary notes sounded, we “stay with the trouble” of disaster media (Haraway 2016). That is, we consider how studying media in the context of disaster helps to expose structural social and environmental disparities incompatible with equity and justice for all. And we explore how disaster media situate people within multiple temporalities ranging from the seeming abruptness of weather volatility and industrial plant explosions to the longue durée of geophysical and biological changes taking place on the planet and in its atmosphere.

People use audiovisual media to tell stories, to convey and persuade, to hail one another, and to document happenings—after or even as they are taking place. We also use media systems to sense and scan the surface of the earth, monitor vehicle traffic on roadways, open and close mobile gates and levees for flood control, and regulate the shutoff valves of oil pipelines (which companies assert can prevent or minimize leaks and spills). Such situated, contingent, computational, and, we emphasize, media-rich operations striate the means through which states, regions, NGOs, communities, citizen scientists, and individuals live and act.

Thinking about these and related processes through the disaster media lens has led us to ask all over again what “media” are and to contend with how, especially during harmful events, media in various modalities proliferate, transform, translate, and inevitably sculpt the environment. Through these processes, media give shape and meaning to disasters themselves, and become integral to the ways disasters are imagined, experienced, and felt. Media also are part of the practices and delivery of disaster relief. “Disaster media,” then, names the project of attuning to ways that media are both complicit in the amplification of disastrous occurrence and helpful in the provision of reckoning and relief, support and succor. This stream continues with our own remarks—possessed by coronavirus media, yet reaching beyond—and with the article by J. D. Schnepf on drone rescues and “ecosensing” and the interview by Kathy Kasic with Jonathan Marquis about artwork at the edge of ice melt. Downstream, more articles will be added.

Coronavirus Media

In early 2020, as we were preparing to write this introduction, people and agencies worldwide were realizing the existence and spread of COVID-19, the severe acute respiratory syndrome brought on by the novel coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). By March the world had encountered this virus not only through person-to-person transmission but also in extensive media coverage on and offline. Despite all of the pressing unknowns of the disease, one cannot call its emergence unpredictable. A simulation by the US Department of Health and Human Services, code-named Crimson Contagion, ran from January through August 2019. The aim was to prepare for the effects of an influenza pandemic. The findings reportedly “drove home just how underfunded, underprepared and uncoordinated the federal government would be for a life-or-death battle with a virus for which no treatment existed” (Sanger et al. 2020).

As we write, the novel coronavirus is resculpting life as we know it, from everyday practices to health-care infrastructures, from government policies to global economies. All of this is happening in and through modes of media and processes of mediation, from the microscopic imaging “at the core of human-virus relations” (Ghosh, Forthcoming) to the myriad types of scientific visualization, from televised government press conferences to the rush online as people observe stay-at-home orders. Media have formed and spread almost as prolifically as the virus and have carried far-fetched conspiracy theories and misinformation as well. As submicroscopic agents capable of growth and multiplication only in living cells, viruses have inadvertently lent their name and agential capacity to media virality. To “go viral” in the media sphere is to participate in a proliferation of social media posts, photos, and videos, including deep fakes, pop-ups, GIFs, memes, and, importantly, ideas via the internet.[3] Through the disaster media lens, the novel coronavirus pandemic appears as a cell culture of elements: satellite images, charts of disease and fatality curves, social media communities of rage and solidarity, in the stew of injustice and climate catastrophe.

Here we acknowledge author and activist Naomi Klein, who has used media (Hasan and Klein 2020; Goodman 2020) to engage the public in resisting what she calls a new “pandemic shock doctrine.” In a short video, Klein describes “the shock doctrine” (from her eponymous 2007 book) as “a brutal and recurring tactic by right-wing governments”: “After a shocking event—a war, coup, terrorist attack, market crash, or natural disaster—they exploit the public’s disorientation, suspend democracy, push through radical free market policies that enrich the 1 percent at the expense of the poor and middle class.” This exploitative “coronavirus capitalism” is happening in the United States during the current pandemic, she argues. For instance, the Trump administration and its lobbyists have proposed “[b]ailouts for fracking companies, not to mention cruise ships, airlines, and hotels, handouts which Trump could benefit from personally” (Klein, Lewis, and Feeney 2020). Of course, as Klein points out, the current coronavirus is not the only global crisis at hand. There is also climate disruption, which has been driven by the very industries “that are getting rescued with our money” (Klein et al 2020). Ultimately, Klein perceives the crisis as an opportunity to catalyze democratizing social change (Klein et al 2020; Hasan and Klein 2020). Embracing this idea, we continue the discussion from our perspectives as media studies scholars.

Satellite media

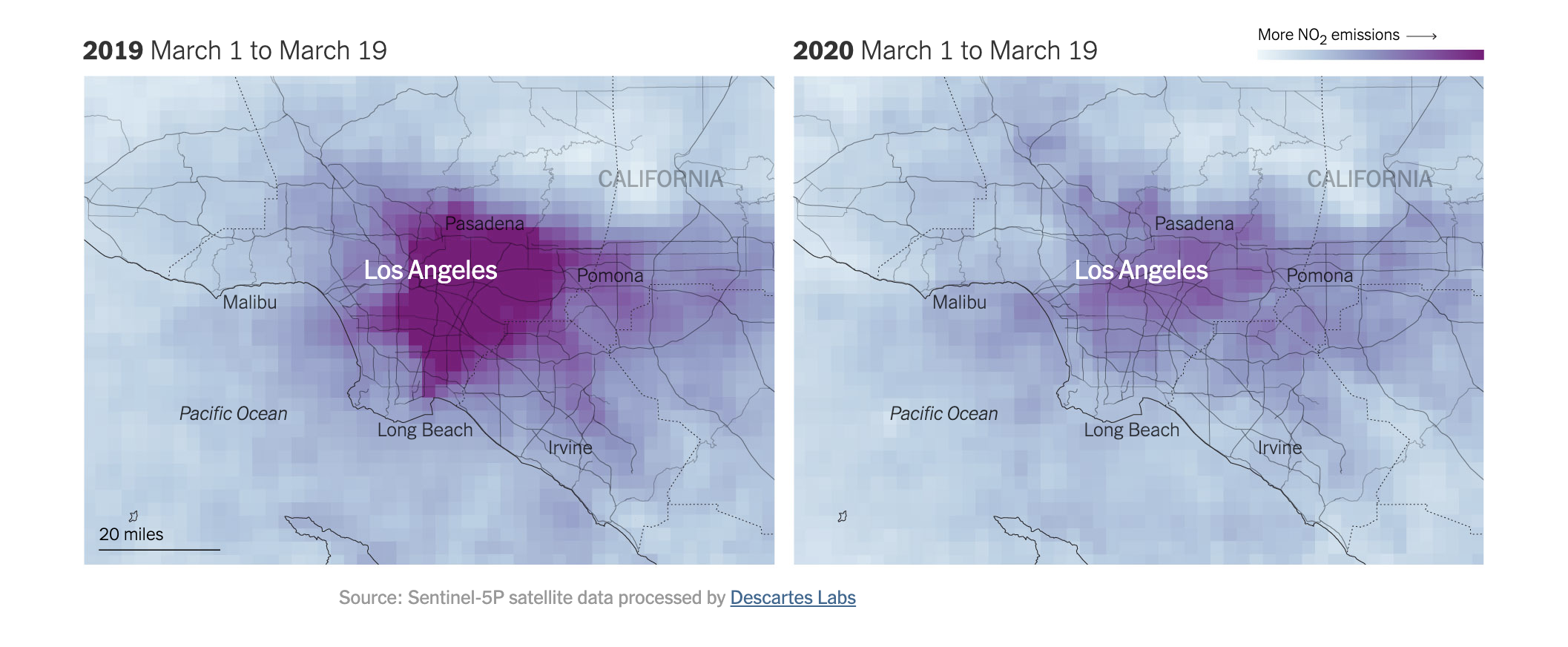

In February 2020 satellite images of mainland China, generated by NASA and the European Space Agency, seemed to reveal a significant decrease in Wuhan’s air pollution when compared with January views. This apparent change in the chemical composition of the air was attributed to the Chinese government’s and people’s efforts to stop the spread of the virus by staying at home and halting or reducing transportation and factory production (Hauser and Jackson 2020). Likewise, over the United States, the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite acquired geospatial data that was interpreted as revealing a significant reduction in nitrogen dioxide levels above US metropolitan areas, including Los Angeles, Seattle, New York, Chicago, and Atlanta, compared with the same period last year. As US roadways emptied, fuel consumption plummeted, and so did greenhouse gas emissions (Plumer and Popovich 2020). The dramatic changes in tropospheric NO2 density were conveyed by color-coded satellite images.

Figure 1a, for instance, uses bright magenta to indicate greater concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and light blue to signify cleaner air. However, such color choices can be misleading: there is no material correlation between nitrogen dioxide and the color magenta; and reduced traces of this chemical do not turn the sky a paler shade of blue.

Moreover, as these color-coding selections imply, satellite images are not just scientific; they are cultural as well. Remote-sensing satellites are equipped with multispectral sensors that detect phenomena across parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. These instruments sense chemical traces in the troposphere and stratosphere based on the reflective or absorptive properties of those chemicals. These traces are captured as sensor data and transmitted to earth stations. There, the data are processed, calibrated, and rendered so that they can be intelligible and readable as satellite imagery. This imagery is then scaled, colorized, and overlaid with graphics that identify phenomena of interest. This “disaster media” formation is highly processed and designed to spotlight phenomena and relations that are invisible to the human eye. The fading, semitransparent pixels above a given city—graphic additions to satellite imagery—while informative in many respects, are legible only in the broader contexts of media literacy and cultural critique. These renderings also may be thrown into question by subsequent satellite data or by more nuanced analyses.

Shortly after these satellite images circulated in the media, other news articles and imagery appeared, emphasizing compounding factors of weather conditions and continuing presence of ozone in the assessment of COVID-19’s impact on air pollution (Barboza 2020). It’s complicated. Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board, told the Los Angeles Times, “it’s not a coincidence” that improved air quality is happening while fewer are driving and the economy is down. At the same time, in relation to the reporter’s question about “how much is due to weather versus pandemic triggered emissions reductions,” she indicated that it “will take us a while to figure that one out” (Barboza 2020). The Los Angeles Times photograph (figure 1b) and the Sentinel-5P satellite images (figure 1a) seem to suggest that reactions to the novel coronavirus have cleared the air, while an expert brings up other complicating factors that must be taken into account in assessing how the novel coronavirus has affected the air over cities and regions around the globe.[4] As digital approximations of remote realities, satellite images always need careful anchoring, comparative review, and updated analyses (Parks 2005), especially in the context of disasters.

Other satellite images that circulated during the COVID-19 pandemic are suggestive of more pressing conditions. With macabre immediacy, Maxar’s WorldView-3 satellite, among others, has remotely sensed the digging of trenches and gravesites in preparation for the interment of coronavirus victims —“earth moving for the dead,” as one headline put it (Howell 2020). This satellite image (figure 1c) reveals the embodied and environmental effects of the virus while also evincing the ideological opacity of unread images. Likely a product of the West’s satellite monitoring of Iran, the image’s circulation displays what happens when privatized “intelligence” meets disaster capitalism: images generated to achieve strategic state objectives are flexibly repurposed to proliferate humanitarian optics. Symbolically, this satellite image, from a US satellite operator, locates pandemic “excesses” in an Iranian “elsewhere.” But this is an increasingly deceptive proposition, given that the United States has one of the highest COVID-19 per capita transmission and fatality rates in the world.

How ironic that satellites from orbit can capture the effects of a tiny virus the naked eye cannot see. Indeed, the satellite is uniquely positioned to sense and help make sense of dynamic material relations taking shape across different events and scales, and to bring together pandemic and climate disasters in the same window of time. Yet, while satellite images of the world during COVID-19 are necessarily partial and selective, they may also enframe a crucial insight: that human choices, physical conditions, and mediation practices actively co-constitute the living and dying world. Whatever the intent of their commissioners, satellite images of graves signal the high stakes of government decision-making, during the pandemic and always. On a brighter note, satellite images of “cleaner air” imply that broadly adopted human behaviors, environmental laws, and regulatory policies could be effective where needed to mitigate air pollution or elsewhere on the climate action front.

Charting the curve

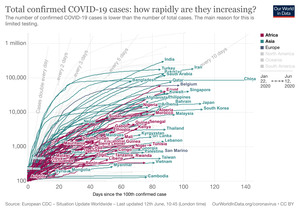

In addition to satellite overviews of the pandemic, the disaster media heuristic has drawn our attention to the global proliferation of charts and, in particular, graphs that display cumulative COVID-19 cases and deaths over time in the form of a linear curve (figure 2a). In these graphic depictions of reported statistics from Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America, we read the rise in cases—or deaths (as in figure 2b), and, in some areas at a certain point in time, a welcome decline in cases and deaths represented by a reduction of the curve’s upward angle or even a downward turn (figure 2c).

As publics, what do we make of these data visualizations and their accompanying discussions? As media scholars, what do we make of them? Whereas satellite images of reduced smog in the air over cities suggest or imply that physical environmental changes can be effected by behavioral and regulatory choices, here in the case of the coronavirus curves, people are being directly charged and thought to possess the collective power to act in a change-making fashion. The hope is that through our individual and coordinated actions, and abiding by municipal and state orders, people of each and every area of the world can slow the transmission of the virus, make the number of patients more manageable, and thereby lower the number of resulting fatalities. Hospitals and medical care facilities around the world and their doctors, nurses, and other staff have been, variously or all at once, valiant, committed, afraid, outspoken, and grievously overwhelmed by the number and sickness of COVID-19 patients and the lack of resources and protocols to treat them. If health care is to have a chance, we are told by public health experts and news media, we need to attenuate the spread of the disease while increasing the availability of testing and the supply of personal protective equipment, ventilators, oxygen, blood, and beds.

With regard to this mediatic visualization of the novel coronavirus, people are assumed to have the power to “bend” or “flatten” the curve. In public discourses, ordinary people are being invested with the agency not only to view or receive graphed statistics but also to intervene in the course of things and their depiction. This is a salient instance of the way in which people, organizations, places, viruses, and graphic media in relation to one another co-produce life and death in the time of a global pandemic.

As COVID-19 curves are being plotted, another widely disseminated graph comes to mind: the global warming curve. Plotting temperature data from hemispheric proxy records over thousands of years (or more), this curve is relatively horizontal over time and then rises sharply at the end of the previous millennium and the beginning of this one. Thus it depicts the daunting eventuality of a warming earth that will no longer sustain life as we know it.

Dubbed the “hockey stick graph,” this data visualization (figure 3a) was familiarized by its use in An Inconvenient Truth (Guggenheim 2006), the well-known documentary centered on the climate activism of former US vice president Al Gore. The filmic version of the graph (figure 3b) shows a doubled line denoting the normal oscillations of carbon dioxide (CO2) parts per million (ppm) and temperature over hundreds of thousands of years of matching up and down squiggles, and their abrupt rise in the present day and projected into the future.[5] Although there is broad scientific consensus around the validity of the hockey stick graph, the visualization has been subject to persistent attack by fossil fuel industry scientists and lobbyists, as well as by a panoply of skeptics and deniers. From a disaster media perspective, the film’s global warming graph depicts a dramatic climate shift, projects imminent catastrophe, and issues a world warning. Its circulation in global media culture for the past fifteen years potentially informs the ways people are engaging now with similar-looking charts of coronavirus death and illness. Historically, news media have relied on sensationalistic photos of human suffering to convey a sense of disaster, but in the age of big data and the current pandemic, numbers speak, and graphs and curves tend to dominate the mediascape. In both cases, scientific experts and publics must grapple with how these graphs make meaning, what datasets they rely upon, and how these media come to stand in for highly complex conditions.

In fact, the graphs of COVID-19 cases and deaths are incomplete, particularly in the absence of widely available testing for the virus and accurate information about the results. The chart in figure 2b from Our World In Data includes this very proviso at the top. There are additional challenges as governments at various levels in the United States and abroad withhold information from the public or fail to determine cause of death or fall behind in counting the deceased, whether in nursing homes, in individual households, or on the streets where people died alone and unnoticed.

The disaster media heuristic encourages us to reflect upon the coronavirus and global warming graphs together and in relation to other audiovisual mediations, which, as we argue throughout, co-produce the material realities they may seem only to depict. Human actions have the potential to shape and change these graphs. When people follow shelter-in-place orders, when essential workers wear protective gear on the job, and when we follow handwashing and mask-wearing protocols, we reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19 and contribute to the bending of the curve, though there are pre-existing inequities and illnesses that continue to pose challenges even when people do follow these orders. Suffice it to say, only collective actions help forestall the spread of the virus, lessen the flow of patients, and bend the curve. Hospital, municipal, state, and other policies have been formulated with “the curve” in mind.

As significant as these data visualizations are in communicating COVID-19 infection and death rates, we think they have a way of effacing human dimensions of the pandemic. This is why the New York Times dedicated its full front page on May 24, 2020 (figure 4), to identifying the nearly one hundred thousand individuals who had been killed by COVID-19 in the United States. It is also why people continually mention and wish to honor health-care workers on the frontlines; essential grocery store, food packaging, and farm workers; and local government officials working around the clock. We are glad to recognize that, in addition to pandemic satellite and data visualizations, workers in many capacities have appeared in the mediascape, perhaps now more than ever, via frank interviews, personal phone videos, protest photos, and social media posts. Communities all around the world are expressing their thanks to health-care workers in pictures (Lane 2020) and, in some places, in synchronization at a designated time with loud ringing praise, howls, handmade signs, and projections of blue light on buildings. This scattered cacophony of gratitude is also part of a disaster media assemblage, as it registers collective awareness of labor at risk and, speaking from the US context, compels us to fix our broken system. The moment satellite images or data visualizations begin to reign info-supreme or become iconic accounts of a disaster, there is a need for analysis of their myriad explicit and occluded meanings. As always, further engagement with embodied experiences and situated knowledges can help to modulate the dominance of and false security in numbers and overviews, and to further flesh them out.

The rush online

As the global circulation of pandemic satellite images and data visualizations implies, coronavirus capitalism is interwoven with digital capitalism (Schiller 1999; Terranova 2004; Fuchs 2019). The pandemic has prompted a massive rush to online spaces of work and leisure activities. It is estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased total internet use by 70 percent (Beech 2020). To meet this growing demand, broadband providers in the United States suspended data caps for users as part of a “Keep America Connected Pledge.” Workplaces and schools dramatically increased their use of online video conference platforms such as Zoom and Google Classroom as meetings and courses became virtual gatherings. Netflix streaming services hit all-time highs for viewing traffic during the coronavirus’s spread and became so overextended that users experienced outages in Europe. Online gaming platforms like Twitch TV also experienced huge gains in user traffic. Social media, too, from Facebook to WhatsApp to TikTok, were blanketed with posts as publics worldwide accessed and shared—or sought to access and share—accurate information (and ignorantly or maliciously disseminated untruths) about the novel coronavirus’s effects. An aspect of coronavirus media going viral includes the user-generated effort to help by creating and spreading memes, videos, artworks, music, and poetry reflecting upon conditions of mass illness and death, disaster declarations, overrun hospitals, equipment shortages, school shutdowns, business closures, emptied grocery store shelves, skyrocketing unemployment, and economic collapse.

Yet with this surge in online activities and virtual gatherings, the COVID-19 crisis has both exacerbated and laid bare the internet’s rising energy dependency, its growing carbon footprint, and issues of energy justice. The challenge is to be able to address crises of various kinds while reducing fossil fuel use especially, and developing sustainable and equitably managed energy sources. There is a burgeoning scholarly literature about the ill effects of the nuclear, petroleum, coal, and hydroelectric energy sources that power the grid and about the environmental devastation their industrial incursions wreak. In the meantime, the impacts of extraction and production of the various energy forms that keep the grid and the internet operating are often toxic and inequitable.[6]

Then, with regard to access, not all people have the resources to go online for work or education. When students were instructed to join online classes from home, many from low-income households or communities have had to scramble for or go without adequate computer equipment, broadband connections, and feasible online study spaces. When jobless people have tried to file unemployment claims online, they have experienced long delays, and government websites often crashed. The online culture of the pandemic exposes a frayed socioeconomic fabric and reveals that the internet will not save us. There is a general need to confront this energy-internet-justice problem via tactics such as assigning energy ratings to digital products and services, creating greener digital technologies (though there is no magic “technological solution”), reorganizing internet access and screen time, and insisting upon racial-environmental justice.

The current pandemic and its mediation are once again bringing structural inequities and hate speech and actions into relief as ongoing disasters in and of themselves and as actionable concerns. It is possible to track the evidence of ingrained biases and exclusions becoming acute during this public health emergency. While we were writing in early April 2020 and subsequently, reports by news media and other institutions were linking systemic health and social disparities in the US to the increased risks that African American, Latinx, and Indigenous people and communities face of contracting experiencing severe illness, and dying from COVID-19 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2020; NAACP 2020). Beyond this, numerous reports of anti-Asian discrimination and harassment surfaced in the US as Trump blamed China for the pandemic, referred to it as the “Wuhan Flu” or “Kung Flu,” and effectively sanctioned racist behavior.

Then, while copyediting this article, the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and many others, set in motion national and worldwide protests to resist and end the historical and unabated violence by police and other law enforcement entities against Black people, and the wider context of anti-blackness and systemic racism. This context includes both the disproportionate number of African Americans getting sick and dying from COVID-19 and the harmful environmental racism called out above. Arguably, it is not since Hurricane Katrina that these potent and lethal injustices have appeared so glaringly in the form of disaster media. We stand against these multiple instances and systems of racism, and call upon governments, societies, and communities to address them going forward.

Given the need for integrated analysis of compounding disparities in public health, water, shelter, electrical, and internet emplacement and access during disasters, we believe that the disaster media heuristic has the potential to repeatedly bring forth socioeconomic fissures and fault lines that governments have ignored yet that must be addressed, and addressed in the contexts of ecological disruption and systemic racism with media materialities in mind.

Gathering Grounds: Existing Research

Over the past several decades, film and media and environmental humanities scholars have investigated various crises, but the resulting research has not really been aggregated or conceptualized under a subdisciplinary umbrella that we are calling “disaster media.” It is certainly true that other disciplines have used an array of approaches to study “disaster communication.”[7] Here we draw attention to film and media studies’ critical attunement to catastrophic events (Ostherr 2005; Keane 2006), mediation practices (Kember and Zylinska 2012; Gabrys 2013; Pisters 2012), and “accidents” (Virilio 1989; Siegel 2014) as well as to “climate trauma” (Kaplan 2015), mediated “migration as crisis” (Lynes, Morgenstern, and Paul 2020), and the “inhospitable world” (Fay 2018). Many works have inspired us and provide context for articles in this stream. In the following discussion, we foreground scholarship on toxic emanations and emissions, on extreme weather and “natural disasters,” on climate disruption and the struggle for sustainability, and on public health, emphasizing the rich and myriad contributions of film and media scholars to disaster media studies.

Earthly destruction wrought by nuclear war and testing has prompted film and media scholars to investigate the unique documentations, material impacts, and geopolitics of nuclear explosion and radiation. Disaster ensued in the instances and immediate aftermath of the Trinity detonation in New Mexico, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, and many other destructive nuclear explosions such as those in and above the Marshall Islands from 1946 through 1958. Disaster persists biologically and environmentally for decades thereafter in the lifeworlds and bloodstreams of those living near strike zones (Perrine 2019; Broderick 2009, 2018; Broderick and Jacobs 2016; Van Lente 2012; Shibata 2018; Barker 2013). Nuclear blasts created atrocities that tested the “threshold of the visible” (Silverman 1995), creating blindness and “beclouded visions” (Maclear 1998), demanding new audiovisual lexicons of annihilation and survival. In Atomic Light (2006), Akira Lippit identifies a “mode of writing and unwriting of disaster that moves from X-ray to atomic radiation and traverses the cinema,” articulating an atomic optics of invisibility (5). Nuclearity has compelled new film and media theories of optics, acoustics, and haptics and has made clear that some disasters simply could not be “represented.”

As nuclear power became part of the global energy economy after World War II, it augured other disasters, such as radiation exposures from African uranium mining (Hecht 2012) and the Chernobyl nuclear plant meltdown, painstakingly detailed in Kate Brown’s Manual for Survival (2019), horrifyingly dramatized in the award-winning television series Chernobyl (2019), and analyzed over decades by film and media studies scholar Adrian Ivakhiv (2018). To engage with the materialities of nuclear and electromagnetic radiation in India, media scholar Rahul Mukherjee (2020), discussing sites in Koodankulam, Tamil Nadu, Jaipur, and Mumbai, develops the concept of “radiant infrastructures” to register how “people try to make sense of radiation-emitting technologies” such as cell towers and nuclear reactors. As Mukherjee explains, these infrastructures “are at once harbingers of development and emitters of potentially carcinogenic radiations.” Media co-constitute the public lives of these unseen phenomena by “molding political imaginaries, bodily prehensions, and social aspirations” (7).

Weather media scholarship is a particular site where contestations of the neutralist conception of the “natural disaster” have taken shape—with Hurricane Katrina a signal event. Writers from many disciplines have discussed the importance of recognizing the social, political, and economic factors that rendered the hurricane-force winds and rising waters catastrophic (Hartman and Spires 2006), in particular for African Americans who in pre-Katrina New Orleans, Louisiana, constituted 67.3 percent of the population yet disproportionately lived in poverty (Park and Miller 2006, 13).[8] In her influential collection Old and New Media after Katrina (2010), Diane Negra argues that “representations of Hurricane Katrina cannot be read outside of a neo-liberal context marked by ‘New Economy’ market fundamentalism, state-supported assaults on the environment, intense anti-immigration rhetoric [and] the withering role of state care for the vulnerable and various other perversions of democracy that have flourished in recent years” (2010, 1).

Film and media scholars have approached weather in other ways too.[9] In her book Inhospitable World (2018), Jennifer Fay demonstrates that weather and war have always served as foundational, if backdropped, conditions of filmmaking. Drawing on examples ranging from the films of Buster Keaton to China’s Three Gorges megadam to Antarctic exploration, Fay critiques the way cinema has fostered humanity’s perception of its own centrality and insists, “We need to learn how to live and die in an unpredictable and increasingly inhospitable world” (11).[10] Extreme Weather and Global Media (2015), edited by Negra and Julie Leyda, also sets out to confront this challenge by studying mediated weather across international sites, including India, Germany, and Japan. Contributors address key questions about the kinds of weather information that media outlets circulate, the relations such outlets have with government and nongovernmental organizations, and how their coverage shapes public perceptions of and responses to “disasters.” These and other media studies epitomize weather media as a kind of gathering ground for structural analysis of the differences and inequalities in the ways that people and nonhuman beings are impacted by atmospheric dynamics, seismic activities, and wildfires as forces that might seem natural but are actually and profoundly social.

A third area of research related to this disaster media formation involves study of environmental media, climate change, and sustainability. Analysis of such issues has historically been led by Indigenous communities worldwide who have used voice, media, and other forms of communication to assert sovereign rights to their lands, resources, and cultural survival and to further traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous lifeways (Tuhiwai Smith 2012; Deloria 1999; Vizenor 1999; Leuthold 1998; Dunbar-Ortiz 2014; Whyte 2013, 2017; Estes 2019; Lowan-Trudeau 2019). These perspectives mandate much broader conceptualization of “disaster media” in relation to histories of colonialism and other kinds of systemic inequalities, mentioned earlier. Indigenous peoples’ recent responses to state and corporate encroachments on their lands—witnessed, for instance, in the case of Energy Transfer Partners’ construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline across lands included in the Horse Creek Treaty (also known as the Fort Laramie Treaty) of 1851—present a basis for other ways of thinking about disaster media. On the one hand, widely disseminated scenes of standoffs between Indigenous Water Protectors/non-Indigenous allies and brigades of heavily armed local, state, and federal law enforcers became iconic disaster media that evinced egregious treaty rights violations and ongoing oppression of Indigenous communities. On the other hand, Water Protectors, including drone pilots Myron Dewey, Dean Dedman Jr., and others, used civilian drones in daily life to document Energy Transfer Partners’ incursions on tribal lands and to track police activities, appropriating overhead media to watch over and protect lands and activists from the sky (Dedman 2017). Under the names of Digital Smoke Signals and Drone2bWild, respectively, Dewey and Dedman livestreamed on Facebook and archived much of their drone footage in an effort to ensure that physically distant communities could witness what was happening as people stood with Standing Rock. This Indigenous formation of disaster media connects the assertion of sovereign land and resource rights that have existed since time immemorial and through the treaty period of the nineteenth century with current actions to protect the land, air, and water from the depredations of the fossil fuel industries, highlighting the important role of media activism in these struggles.

Film and media scholars have also drawn attention to the need for “greening the media” (Maxwell and Miller 2012; Vaughan 2019), “eco-media” (Cubitt 2005; Rust, Monani, and Cubitt 2015), or “sustainable media” (Starosielski and Walker 2016). Our field cannot afford to ignore the relation of film and media technologies and industries to extractive industries, energy consumption, and global climate change. Doing so, these scholars argue, would prove disastrous. An entire cycle of film and media scholarship has taken shape to tackle these issues; in fact, the open access Media+Environment journal was formed in part to provide a platform for this research, and the Journal of Environmental Media was also launched at the end of 2019. By focusing on climate-related disturbances such as glacial melts, sea-level rise, species extinctions, atmospheric warming, and other matters, environmental media scholars have expanded the scope of the field, insisting upon the need to investigate elemental media and practices of mediation involving different kinds of sites, temporalities, and materials—from water to fire, from salt to ice (Peters 2015; Ruiz 2018; Jue 2020; Young, in progress). Such work, for instance, encourages critical thinking about disaster media in relation to geologic time (Parikka 2015), cinematic footprints (Bozak 2011), video game play and scientific research paradigms (Chang 2019), programmable earth interfaces (Heise 2008; Gabrys 2016), or the wiring of media into nature (Schwoch 2018). The interdisciplinary openness of film and media studies has prompted scholars to engage with scientific fields such as geology, meteorology, biology, and oceanography in the process of exploring how media participate in, produce knowledge about, and themselves materialize climate-related disasters and practices of earthly destruction.

A final trajectory we wish to mention relates to film and media scholarship on public health. This work not only serves as crucial context for the COVID-19 pandemic but also extends the conceptual contours of disaster media to include disease and illness, outbreaks and pandemics, and the ways government agencies address or fail to address health-related crises. Alexandra Juhasz’s book AIDS TV (1995) explores community educational initiatives and activist videos that became vital means of conveying information about and perspectives on HIV transmission during the 1980s and '90s and continuing public health crises. Addressing media portrayals of other outbreaks, Kirsten Ostherr’s Cinematic Prophylaxis (2005) critically examines Hollywood films “that represent the spread of contagious disease across national borders.” In it Ostherr argues, “Audiovisual materials play a crucial role in the articulation of world health, not only as vehicles of educational and ideological dissemination, but also as metaphors for the spread of disease within the processes of globalization” (2). Her study sheds light on the current COVID-19 crisis by demonstrating how outbreaks become disaster media.

Other scholars have approached public health issues from perspectives of narrative analysis and elemental media to demonstrate how disasters emerge at different scales, temporalities, and levels of intelligibility. For instance, in her book Contagious (2008), Priscilla Wald describes the microbes, super-spreaders, and hot zones that make up “outbreak narratives” and explains how these narratives impact survival rates and contagion routes. And in her work on “epidemic media,” Bishnupriya Ghosh questions the distinction between “human” and “microbial” matter and explores how HIV/AIDS viral load tests function as “epidemic media engaged in slowing down, abating, and sometimes thwarting planetary disturbances” (forthcoming, 5). Ghosh details how the mediatic capture of blood is used to distinguish and “read” viruses entangled in symbiotic, multispecies relations, and how these processes are implicated in “managed HIV.” Both Wald and Ghosh think across scales of the microbial and the global and, in doing so, evolve critical understandings of media, biology, and ecology in ways that will inform future disaster media research.

As this discussion suggests, the study of media and disaster has been pursued variously and in ways that lend salience and heft to this current disaster media heuristic and material formation. In what follows, we offer three brief provocations that stem from these considerations and signal the need for further engagements.

Provocations

All media on deck!

Because disasters materialize in myriad forms, across multiple sites, at various times, we need all media on deck in order to understand and formulate effective and just responses to them. At a time when nation-states have their own reasons to be behind the curve or are even refusing to act at all, let alone in egalitarian, humane ways, individuals and groups must use whatever mediated means necessary to investigate and intervene in calamitous happenings. If ever there were a need for public media, it is at moments such as this one when mediated disasters abound. People must draw and critically reflect on a mixture of media—from flow diagrams to films, from satellite images to sound files, from mobile phone apps to artworks—to collectively make sense of and respond to accumulating harms. And if ever there were a need for media literacy and open access information, it is now, when the world faces the overdetermined crises of global climate disruption and viral pandemic and their inherently unjust machinations. Media have become vital cognitive and political tools, enabling publics to reckon with the immanence and systemic substrate of disastrous occurrence. We need all media on deck and critical media literacies fully activated to resist, intervene in, and ameliorate the status quo.

Of course there is this profound conundrum foregrounded by sustainable media studies. Even as we call all media and critical media makers on deck, we recognize media’s heavy energy footprint. Given this dilemma, the media we create, share, and consume over the next decade will need to differ from current configurations and to be used conscientiously as well as effectively.

Equitable relief as the outcome!

As has been the gist of this introduction, rather than approach disaster media as disturbing spectacles lamented from afar, we need to think more seriously about how media figure into the availability and provision of equitable relief. Such a proposition includes considering what is meant by “relief” and delineating various mediatic forms it might take, as J. D. Schnepf does in the article to follow. Whose voices and experiences are attended to, and how are they heard and prioritized? Which combinations of “first response” and an undergirding social safety net bend toward social and environmental justice? How are opportunities for disaster relief produced and implemented within relief agencies in and beyond the neoliberal state? Furthermore, we might consider what conceptions of disaster media and disaster relief are held by government and nongovernmental organizations as they produce videos, build websites and online resources, map neighborhoods and displaced peoples, and create algorithms to predict where disasters might strike so that equipment, supplies, and medicines can be moved into place.

This area of study could benefit from production culture studies conducted of the media industries (Caldwell 2008; Mayer, Banks, and Caldwell 2009), which, among other things, delve into the labor of pressurized mediamaking. We encourage similar research on production cultures of disaster relief in and across organizations such as FEMA, NOAA, the Red Cross, UN Relief, Disaster Relief International, Human Rights Watch, the World Health Organization, the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES), 350.org, the Sunrise Movement, Extinction Rebellion, Peoples Climate Movement, Narmada Bachao Andolan, International Rivers, Public Lab, SkyTruth, Our Children’s Trust, the Indigenous-led NDN Collective’s COVID-19 Response project, or the Salvation Army. (This list is far from exhaustive, and the fact of so many sources of effort is heartening.) How can the concept of disaster media be used to support communities impacted by disasters in the near term and also, importantly, facilitate progressive social and environmental transformations in the long term?

Let social and environmental justice ring!

We intend this disaster media heuristic to expose the need for massive structural reform and deepen the connections of media uses and scholarship to it. As activists, protectors, and many other informed and committed persons have been arguing, we must decolonize governmental configurations and reverse the effects of “slow violence” (Nixon 2011) stemming from histories of colonialism, slavery, and extraction. In the broken democracy of the United States, extreme inequity is baked into the ways publics are positioned relative to education, employment, health care, the prison system, and other spheres, with business as usual holding sway. As Klein, who is both a scholar and a public intellectual, has been arguing, disaster capitalism is socially and environmentally unjust as well as biocidal. Vital feminist work on intersectionality (Crenshaw 1991; Ducre 2018) has revealed the necessity and challenge of waging political struggles along multiple social fronts at once. International movements and lifeways to protect the earth are now made up of ethnically diverse, multigenerational communities and often led by Indigenous peoples and people from affected communities. In moving forward, it will be crucial to approach disaster media as a domain in which structural reform agendas that interweave social and environmental justice can flourish.

Resonant with our first provocation, the tactics of reform movements and materiality of activist media will need to change if we take environmentalist media critiques seriously. Activists concerned about climate change are adopting no- or low-carbon media to communicate their messages. Consider, for instance, #NatureNow (Mustill 2019), a short three-minute and thirty-nine-second “zero net carbon” film, featuring Greta Thunberg and George Monbiot, produced with no flights and recycled footage. While we applaud such projects, as media scholars, we are well aware of a longer history of low-carbon media precursors. Such practices have persisted, for example, in the “small media” (Spitulnik 2002) of African communities, where posters, graffiti, cartoons, flyers, rumors, jokes, and “pavement radio” have served as crucial alternatives to mass media. Low-carbon practices are also evident in the “interstitial” media of the displaced and the exiled, often made with limited resources and mixed materials (Naficy 1999). And, as we shall see, the low-carbon impulse is both guiding and manifest in the glacier photography of artist Jonathan Marquis, too, as discussed in Kathy Kasic’s interview in this stream. While communities faced with scarcity and precarity figured out long ago how to produce low-carbon media, whether by choice or by necessity, these tactics need to be more fully recognized, studied, and embraced by the media affluent. Such research could encourage mediamakers to help mitigate the disaster of climate disruption and work to ensure that energy-conscious media are equitably available during times of disaster. The disaster media link to climate change compels us to make structural adjustments to our economies and everyday practices.

The Stream

The arrival of J. D. Schnepf’s essay across our virtual threshold was a key event in the realization of this stream. Some years ago, the two of us had attended a talk by Google Earth strategists. The topic of discussion was how the earth-rendering program could be made more precise and useful for disaster relief with the help of volunteer geographers charged to map and measure their own neighborhoods for official inclusion. While the ideas of participatory geography and user-generated data may seem attractive, the reliance on free labor (Terranova 2004) to consolidate a commercial venture—under the rationale of disaster response—raised questions in our minds about digital privatization, citizen sensing, and neoliberal governance.

Schnepf’s article is deeply informative in this context. Beginning with a story of a drone-assisted rescue, Schnepf explores the increasingly common reliance on social media platforms as a means of seeking help from volunteer rescuers during environmental disasters. “That’s my brothers [sic] house… He’s trapped upstairs,” one man tweeted during a North Carolina flood. But who are the people and communities relying on such practices? Which entities stand to benefit? And how is this arrangement promulgated? Focusing on the figure of the private drone operator in the broader context of ecosensing, Schnepf demonstrates the joint articulation of mediation practices, terrestrial infrastructures, and the political will to rescue. The article presents striking, productive insights about the negotiation of responsibility and rescue when people and communities are made vulnerable by infrastructural inequalities and the monopolization or sequestration of public resources.

The second piece in the stream features an artistic intervention in disaster media. It comprises a gallery of cyanotype images from the photographic series Downwaste, created in Glacier National Park by Jonathan Marquis, and an interview with Marquis by environmental filmmaker Kathy Kasic. This is a virtual meeting—and collaboration—between two innovative artists working with land-based ice and the various worlds and earthworks that the ice has shaped, witnessed, harbored, and hosted. As we learn from the conversation, about a year ago Kasic participated with a National Science Foundation research team in a trip to Antarctica, where she filmed scientists painstakingly probing for life-forms in a heretofore unexplored subglacial lake.

We are pleased to present Marquis’s images, some of which may be seen only in this venue, along with the interview’s deep dive into the process through which these works were created, and their aesthetic properties and possible meanings at a time of rapid changes in the configurations of land-based ice.

“Downwasting,” explains Marquis, is the glaciology term for “the thinning of the glacier due to melting ice.” He uses it to refer to “the site of the artwork’s production,” as one of runoff, sedimentation, and layering. Kasic’s informed questions prompt Marquis to discuss and reflect on his creative process, from practicalities to conceptual and philosophical aspects. The work is nonrepresentational, as they discuss, with Marquis describing his resistance to seeing the images as Rorschach tests. Do the cyanotype squares have an up and a down?, Kasic asks. It’s the flow of the water due to gravity, Marquis explains. He regards the glaciers as “meaningful actors,” the landscapes as “coinhabit[ed]” by humans and glaciers, and the art project as a collaboration with the ice.

Temporality is a significant consideration of both Schnepf’s article and the Kasic-Marquis interview, with the respective orientations to time differing in some aspects and harmonizing in others. While Schnepf evokes the urgency of emergency rescue, Marquis and Kasic concentrate on the deep time of glacier flows. It is important to acknowledge that the glaciers are still here and not already gone, explains Marquis, so as not to deflect responsibility for our actions in the present. Yet the extended time of global warming also undergirds the superstorms and catastrophic flooding that set Schnepf’s media analysis in motion. And then, for its part, the Marquis-Kasic interview brings up both the short summer windows of Marquis’s process and the fact that glaciers “can also do things quite rapidly…” “Large sheets in Antarctica can break off in huge chunks in a matter of moments,” Marquis reminds us. “Time does seem to be a central element to all of this,” observes Kasic.

Media are co-producers of disastrous events that form in and through the inequities they deepen and the earthly disruptions they so often accelerate. Here we have offered some thoughts, in concert with those of others, to critique the status quo and engender solidarity with the calls for equitable relief and just societies being sounded in the current moment.

The title of this essay is inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.'s powerful use of the statement, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” in Montgomery, Alabama on March 25, 1965 after the walk from Selma, and on other occasions. The quote is attributed to the Unitarian Minister and abolitionist Theodore Parker.

We use the term climate disruption rather than climate change throughout our introduction to emphasize the adverse material impacts that industrial and post-industrial capitalism have had and continue to have upon the earth’s environment.

Scholars have theorized media virality with concepts ranging from the “viral infections” and “benign mutations” of culture jamming (GALA Committee 1998) to early “viral videos” on YouTube (Lovink and Niederer 2008; Burgess and Green 2009) to “spreadable media” across multiple platforms (Jenkins, Ford, and Green 2013).

Paradoxically, a subsequent study about the influence of aerosol particles on cloud brightening (Diamond et al. 2020) suggested “some air pollution actually reduces [global] warming” by “bounc[ing] the sun’s rays back into space” (Simon 2020).

Walker (2015) has discussed this film in relation to her ongoing project to develop a “geographically induced heuristics” for documentary studies, a foundational premise of which is the affinity between site-specific documentary films and other geolocational media.

Damaging energy production activities are often sited in or near low-income communities or communities of color (Pezzullo 2007; Shamasunder 2018; Estes 2019). In fact, even the production of photovoltaic cells for solar panels and arrays can disturb ecosystems when not carefully handled (Mulvaney 2019) and, in places, entail the dispossession of farmers and the construction of new coal-fired power plants. Jia-Ching Chen points out that “low-carbon value is not the material, political-ecological other of high-carbon petro-modernity” (Chen 2018).

Disaster communication research often uses social science methods to analyze content and effects of journalistic news media and social media coverage of disasters. Examples of this research include Moeller (2006); Pantti, Wahl-Jorgensen, and Cottle (2012); Cottle (2014); Landwehr and Carley (2014); Greenberg and Scanlon (2016); Houston, Spialek, and First (2018); McKay and Perez (2019).

Post-Katrina documentaries offer a critique of the racialized social ecological contours of disaster, with Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006) and the sequel If God Is Willing and da Creek Don’t Rise (2010) as affecting cases in point. The systemic problems these documentary series expose include but are not limited to insufficient and unequally allocated federal funding for hydrological engineering projects; lack of federal aid for rescue operations while people were stranded in the flooded city without food or water for days; and in the rebuilding phase, uneven access to health and homeowner insurance benefits.

In Weather as Medium: Toward a Meteorological Art, Janine Randerson explores weather-driven art projects in this time of climate crisis, hearkening to works by Aotearoa-New Zealand kinetic sculptor Len Lye and Fluxus performance and drawing in contemporary pieces such as Severe Tropical Storm 9301 Irma, by Billy Apple (2002–15).

In Climate Trauma: Foreseeing the Future in Dystopian Film and Fiction (2015), E. Ann Kaplan suggests how audiences might learn from the nightmare scenarios of movies such as Children of Men (Cuarón 2006) and Take Shelter (Nichols 2011) so as to forestall the catastrophic futures they depict.