“When is seeing not knowing?”

—Peter Galison and Caroline Jones (2018)

Visual investigations (VI) begin with an act of scraping, of searching through vast and often incomplete archives with the hope of finding sensible evidence of a crime. The actors that visual investigators seek to hold accountable—war criminals, cops, corporations, corrupt government officials, and other representatives of the state—have proven especially challenging to prosecute. This is because historically the law has not always been a viable tool to police its own ruling bodies, at least until human rights abuses morph from political crises to adjudicable offenses. Further, the law has an uneven relationship with the visual. Positivist fantasies of the image’s “self-evident” nature have historically been undercut by the deeply narratological structures of the courtroom.[1] In the wrong hands, an image can become a powerful illusion of transparency. The domain of visual investigations seeks to redress these norms and protocols by enacting a form of sousveillance: by using the tools of surveillance against those who are behind the camera—policing the police, watching the watchers—false narratives of the state are uncovered and amended.

A recent exhibition, “Visual Investigations: Between Advocacy, Journalism, and Law” at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, presents a collection of case studies by SITU Research, Bellingcat, Killing Architects, and the Center for Spatial Technologies in collaboration with Forensic Architecture and Forensis. The exhibition offers a dizzying array of VI tools and techniques, from 3D event reconstructions to 4D analyses, remote sensing to machine learning simulations. For anyone who is not an architect or a visual investigator of some kind, walking through the exhibition can be alternately revelatory and bewildering, alluring and alienating, often in equal measure. The exhibition is organized with careful attention to the fact that much of what is on display is hard to watch. The violent images and sounds of human rights violations are masked by walls, transparencies, and soundproof curtains, which produce a space that moves quickly between public and private (figures 2 and 3). Navigating through these selective opacities amplified the epistemological ambivalence at the heart of the exhibition itself: Is this art, or is this evidence? Playing one territory of knowledge off the other is what structures the field of visual investigations.

The exhibition is among the most expansive surveys of visual investigations since its conception roughly fifteen years ago. However, parsing a comprehensive timeline for the heterogeneous medium of VI is difficult, if not misleading.[2] It is important to acknowledge the fact that while each group in the exhibition has contributed to the development of VI as a medium—now a mainstay in popular news outlets and contemporary art museums—its current format is but one in a long lineage of cultural techniques that seek to produce evidence of state violence through recourse to the visual.[3] Bellingcat’s The Sound of Bullets (2023) offers a paradigmatic example of a visual investigation.[4] Six videos of the killing of Colombian journalist Abelardo Liz are synchronized and played back in real time. Through careful visual and aural analysis, it becomes clear that what actually happened on the ground (the soldiers shot first) contradicts the narratives of the state (the civilians shot first). The rhetoric of visual investigations is satisfying by design. Since the work is typically meant to operate in legal and journalistic contexts, its form must adhere to a certain positivist aesthetic, whereby images can become evidence without interference. Regardless of their particular technical interventions, most of the works in the exhibition are furnished by first-person testimony, whether through direct documentation of witnesses on the stand or through “situated testimony”: a technique wherein witnesses narrate their personal experiences while wading through the digitally re-created world produced by the visual investigator (Forensic Architecture 2024; figure 4).[5] These particular scenes, which connect material experience with technological simulations, bring to light what is a guiding premise for the field: to democratize the tools of visual investigations for a larger populace, or what Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman (2021) call an “investigative commons.”

The (non)linear relationship between images and linguistic testimony has been subject to critique since the introduction of photographs into courts of law in the mid-nineteenth century. In her account of this pivotal moment in legal history, Jennifer Mnookin details the extent to which images “threatened the hegemony of testimony,” given their capacity to provide representations that were so powerful, they appeared “almost to compel belief” (Mnookin 1998, 56, 3). Images endangered the word as the primary narrative agent of the courtroom. The advent of nonfiction cinema heralded a new era of contestation, as early ethnography’s quasi-objective logics—rendering non-Western people as “raw data”—were established in tandem with film’s slow integration into the court’s visual field (Tobing-Rony 1996, 14).[6] Generations later, the case of Rodney King demonstrated that even the most self-evident video evidence can be used on both sides of the legal divide to offer wholly divergent claims to truth, typically resulting in acquittals for cops and their fellow state actors.[7] Further, the idea of “witnessing” has itself been thrown into relief by broadcast news and its accompanying aesthetics of immediacy and neoliberal humanitarianism.[8] Images, with their constantly shifting epistemologies of visibility and authority, continue to undermine traditional hierarchies of judicial authority. The Pinakothek der Moderne exhibition is a testament to this ongoing truth.

Visual investigations do not operate solely by media becoming testimony; their media must also become environmental. It is no coincidence that this show took place at an architecture museum, a showcase for the cutting edge of the built environment. Each piece spatializes its chosen datapoints through various techniques of immersion, producing a vivid sense of architectural verisimilitude. Killing Architects’ Investigating Xinjiang’s Network of Detention Camps (2018–20) offers an instructive illustration of VI as environment (figure 5). The piece moves us through a series of images, drawings, interviews, and meticulous simulations that create a composite image of “what life is actually like for detainees […] in a much deeper way” than a typical journalistic exposé.[9] We are enveloped. We are convinced. We feel ourselves roving comfortably alongside each diagram, line, and arrow—an embodied twin to the visual investigation. At the same time, I also become an easy consumer of whatever information is presented before me, susceptible to what Robert Pfaller (2020) calls “interpassivity”: a process whereby politics are performed for the spectator, allowing them to consume with impunity. This sense of seduction is brought about by a lack of open-endedness in the work’s composition. In trial, images and speech merge into a single ideology of testimony. The works on display here do just that.

Consequently, there arises a certain contradiction between the field’s formal “environmentality” and its closed-circuit construction.[10] On one hand, these are not artworks; they are environments of data. First-world imaging tactics applied to second- and third-world conflicts. On the other, the ambiance of visual investigations is not entirely void of atmosphere—that hazy, porous “thing” that mediates between subject and object (see Brown 2021; Böhme 1993). Even in the hollowed out non-space of the architectural design, there remains an element of aesthetic contingency, even if it’s being geolocated into our view. The environments of VI are not explorations of space, per se, they are hyperspecific reductions of its social conditions. In this sense, VI can be understood as an important explication of the environmental turn in media studies.[11] The virtue of thinking with things as media—as actors, or “agencies of order,” in mediation with ourselves—lies in our capacity to rethink our ethical obligations to them (Peters 2015, 1). If visual investigations can be said to mediatize an object, to make some thing environmental in response to a specific crisis of thought, that object is the law. In so doing, the VI spectator comes to inhabit an ambivalent position: situated between viewer and juror, museumgoer and expert witness.

One piece stopped me in my tracks. In Documenting the Death Flights (2024), by SITU Research and Central Prodh, a chronicle of Mexico’s history of enforced disappearances during the dirty wars, we are prompted to listen to six testimonials about the “persecution of sex workers,” “persecution of journalists,” “persecution of military officials who refused to engage in illegal repression,” and “persecution of migrants and political exiles,” as well as “torture and arbitrary detention” and “disappearance in 1988” (figure 6).

In contrast to the ultrasophisticated schematics that dominate the exhibition, here testimony slows to the pace of the voice, and becomes DIY—to be listened to and carefully considered, one by one. We lose sight of the network, no longer held in the safety of architectural utopias of photo-negative space. Paradoxically, this is a radical departure in form, owing to a careful documentary approach as opposed to the fast mechanics, or “hyper-aesthetics,” of architectural design (Fuller and Weizman 2021, 57).

Unlike art, the matter of visual investigations is not resistant to language. Yet the drama of what unfolds in front of the technoscientific camera of visual investigations does resist. Outside the frame of testimony, VI deals in real bodies experiencing real pain. Before the “incontestable reality of the body” is stripped away, separated from its source and transposed into testimony, what we are seeing and hearing are war crimes (Scarry 1985, 130). The same can be said of the entire field of journalism, with its moral imperatives for a kind of justice that doesn’t always have time to consider the ethics of instrumentalizing images of human suffering. However, by staging the work of VI in a museological context without regard for this transformation in values, real violence becomes readymade.[12] Through the practice of VI, images undergo a process of translation: Images are transformed from being unstable/non-self-evident to stable/self-evident. When VI is put on display in the museum, an institution that is decidedly neither a courtroom nor a newsroom, its images shed their self-evidentiary status. There was little awareness of this fact on the ground of the exhibition, which left little room for interpretation.

I hesitate to call VI into question, for how could its ends not justify its means, with its proven record of countering statecraft and holding violators of human rights accountable. Why should visual investigations slow down? Visual investigations are an ultramodern medium of aesthetic inquiry.[13] And with the advent of any medium, perceptions are retrained, contracts to the real rewritten. That this particular covenant comes with an increased necessity for technological innovation, and with it a dependence on the visual investigator as master translator, seems to be an old problem. Museums have never been neutral spaces; difficult encounters make and unmake the museum experience.

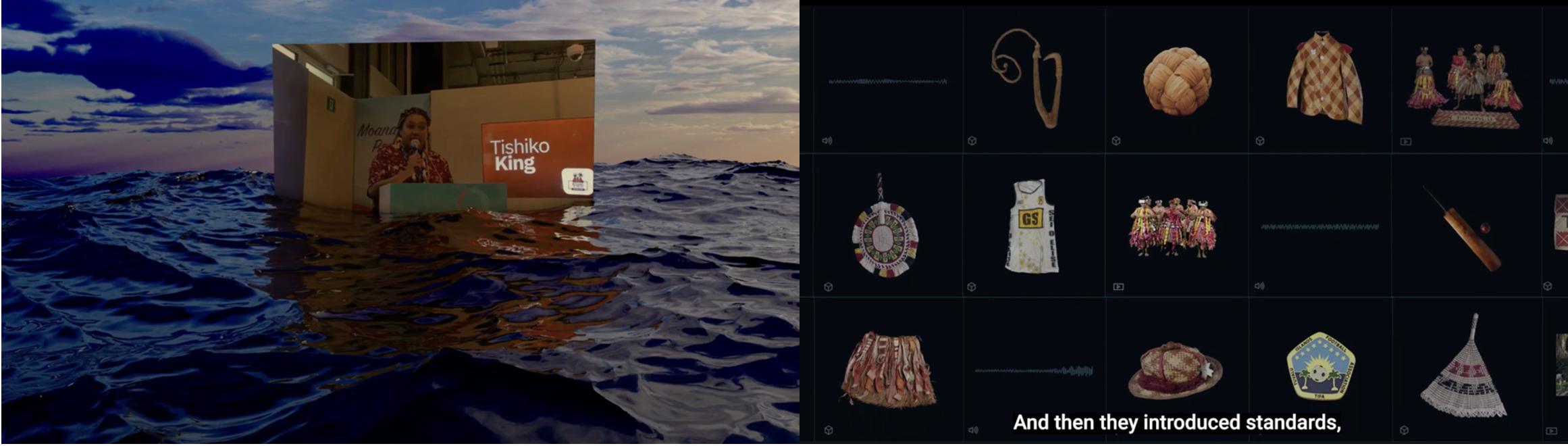

There is one piece of art in the exhibition: Suneil Sanzgiri’s What is Owed?: Taking the Climate Crisis to the World’s Court (2024), a formally heterogeneous portrait of climate activism in the Pacific Islands[14] (figures 7 and 8). Rather than making a film about ecology, Sanzgiri ecologizes the film form with rigor and power, combining archival footage with 3D animations as activist testimonies swirl across the screen, buoyed by the ocean. Despite using many of the same technical tools, Sanzgiri actively works against the logics of visual investigations, exploding its closed system of signs.[15] By taking a nonlinear approach to the synchronization of its parts, What is Owed? uses the medium as a contrapuntal knowledge system capable of transforming colonial relations of property and value. The work reminds us that it is through the dislocation of sound and image, with its unlikely and improper juxtapositions, that film/video has shown itself to be capable of inhering a radical political sensibility.[16] This is the medium’s primary process, from Sergei Eisenstein to Barbara Hammer, Third Cinema to Harun Farocki’s “operational image.”[17]

In visual investigations, there are very specific conventions for how images and sounds are meant to operate. The museum poses an opportunity for these conventions to be broken, experimented with, and perhaps revised anew. Yet the curators of Visual Investigations opted to remain in the vitrine—safe and secure in the spectacle of humanitarianism. It is not the job of the visual investigator to open up a space for ambiguous politics or reflection. Yet as the law itself slowly expands its epistemological purview to account for complex multicrises like global warming, the toolkit of visual investigations may need to expand more toward art than architecture if it is to survive beyond the technology of the built environment.

Author’s Note

Deepest gratitude to Benjamin A. Barsky for his legal expertise and editorial assistance.

As Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman (2012, 23) make clear: “[N]o object appears in court without an expert to present it. The evidentiary value of the thing depends, at least in part, on the authority (probability) of the expert who publicly deciphers it.”

This is reflected by the timeline that orders the exhibition, which pieces together “An Incomplete History of Visual Capture and Simulation” from sources as disparate as Eadweard Muybridge’s experiments in animal locomotion to the advent of CCTV. VI does not have a single unitary definition, nor is it bounded to any particular institution—e.g., journalism, architecture, lawfare. Instead, it can be understood as an evolving array of audiovisual techniques used by an increasingly diverse number of disciplines united under the general premise of combating state repression and violations of human rights. (See Rangan 2025.) While Global North organizations like those on display in the exhibition are often invoked as exemplars of the medium, this can come at the cost of adequate recognition both of their collaborators, who are operating in war-torn regions around the world, as well as the larger history of visual investigations when considered as a form of social activism. Despite its limitations, I employ this chronology because three of the organizations represented in the exhibition, each of which was an early practitioner of the current methodologies that define VI (albeit partially)—Forensic Architecture, SITU Research, and Bellingcat—were founded between 2010 and 2014.

The history of VI draws from a diverse number of media practices, including data visualization, photojournalism, documentary film and photography, artificial intelligence, and architectural simulations. (For a genealogical autobiography of visual investigations, see Forensic Architecture 2014.) Part of what separates VI from its predecessors is its formal transposability and interdisciplinary nature. Visual investigations, in VI’s current iteration, are often undertaken by VI groups and external organizations across legal, journalistic, and humanitarian contexts. An individual VI project can also take on multiple forms depending on its exhibition venue. For example, the most public-facing practitioners of visual investigations, Forensic Architecture, have had their work admitted as evidence in international criminal courts and have shown work in art and architecture biennials, including Documenta 14 and the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Similarly, Investigating Xinjiang’s Network of Detention Camps is based on a series of reports by Megha Rajagopalan, Alison Killing, and Christo Buschek for Buzzfeed News. After its initial publication in 2020, the piece was expanded and re-presented at the 2023 Venice Biennale. Another piece on display at the exhibition, SITU Research’s US Policing and the Suppression of Dissent (2020 and 2022–23), a collaboration with Human Rights Watch and the National Lawyers Guild’s BLM/Floyd Litigation Task Force, was used in a class-action lawsuit against the New York Police Department that resulted in a historic settlement for the plaintiffs in 2023.

This piece was produced in collaboration with Cerosetenta, a citizen-research organization and media outlet based in Colombia.

For an analysis of documentary film’s capacity to “bear witness” and enact forms of testimony, see Sarkar and Walker (2010).

Moving images were first used as a form of evidence in Fenny v. Young (1920). See Shwartz (2009, 4).

Frank P. Tomasulo (1996, 82) argues that the Rodney King case effectively reversed positivist paradigms of vision and knowledge: “they see things only when they already believe them.” Thus, there is no vision without preconceived bias; we cannot see without belief. For further arguments regarding the value of motion pictures as evidence, as well as the importance of the George Holliday tape to the role of media in the writing of history, see “The Rodney King Case, or Moving Testimony,” in Shwartz (2009, 105–20); Butler (1993, 15–22); Stonehill (1992).

For accounts of the extractive logics of participatory documentary and the humanitarian emergency as a televisual “genre,” see Rangan (2017); Williams (1999, 292–312). The evidentiary role of witnessing has also expanded beyond the “flesh witness” toward digital infrastructures of “material witnesses” that index their own sensible claims to truth. See Chouliaraki and Al-Ghazzi (2021); Schuppli (2020).

This quotation is taken from Megha Rajagopalan’s narration of Investigating Xinjiang’s Network of Detention Camps (25:11–25:16). See Allan Sekula’s “The Body and the Archive” for his pathbreaking analysis of Francis Galton’s composite portraits as a method of condensing the archive into a single image, as opposed to Alphonse Bertillon’s anthropometric methods (Sekula 1986).

Giuliana Bruno (2022, 128) makes the important point that media becoming environmental involves not only spatialization but also “mesmerism”—a dangerously manipulable condition when considered from the vantage point of the law.

The intersection of ecological thought and new media theory is extremely diverse, ranging from new materialisms to Black geographies, as well as feminist science and technology studies and more-than-human anthropology. It is an ever-expanding critical conjuncture rather than a unitary field of study. The theorists whose work has been especially instrumental to my own understanding of its radical potential are Katherine McKittrick, Kathryn Yusoff, Donna Haraway, Eduardo Kohn, Anna Tsing, Christina Sharpe, Yuriko Furuhata, Karen Barad, Timothy Morton, Elizabeth Povinelli, Amanda Boetzkes, Jane Bennett, James Nisbet, Bruno Latour, Emanuele Coccia, Peter Galison, and Lorraine Daston.

Centro Prodh’s headsets begin to resonate with Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence (2017); Bavarian police’s use of 360-degree motion capture to simulate crimes starts to resemble Marina Abramovic’s Rhythm 0 (1974); the totalizing aesthetic of Charles and Ray Eames’ Glimpses of the U.S.A. (1959) reverberates through the aggregated screens of police bodycam footage in SITU Research’s US Policing and the Suppression of Dissent.

By using the term “ultramodern,” I am not wagering a univocal claim regarding VI’s “newness.” Instead, I am drawing attention to certain of its formal methods that incorporate technologically sophisticated modeling tools as well as artificial intelligence, which fuse into an ambivalently technocratic, quasi-futurist aesthetic experience.

The piece was developed in collaboration with SITU Research, the Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change, the World’s Youth for Climate Justice, and the University of Chicago’s Global Human Rights Clinic.

Postcolonial anthropologists, environmental media theorists, and art historians alike continue to expand upon Charles Peirce’s semiotic system to uncover emerging, interspecies, and multimedia forms of the “sign.” See Ivakhiv (2013); Kohn (2013); Nisbet (2021).

Sylvia Wynter (2000, 25) proposed that, more than any other medium, film is capable of redefining “what it is to be human.” Film is singularly positioned “to effect our common human emancipation from this memory”—the memory of Western Man (Wynter 2000, 29).

Farocki first used the term in his Eye/Machine III (2003) to define images made by and for machines—images that are part of a process rather than mere representations. In Farocki’s words, they are images “without a social goal, not for edification, not for reflection.” Further accounts of the operational image can be found in Paglen (2014); Parikka (2023).