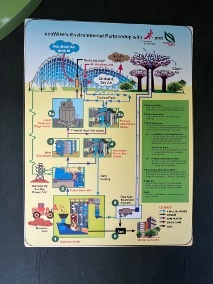

In Cloud Forest, Singapore’s tropical climate is transformed into cool montane forest through climate-controlling architecture and artificial weather. Walking along its aerial walkways, one is enveloped in a mist of cool, moist air, a welcome reprieve from the sauna-like conditions outside. Mimicking a real highland forest, the glass enclosure features epiphytes pinned perfectly on trees growing lushly around a giant, indoor man-made mountain. A glasshouse conservatory, Cloud Forest houses plant species non-native to Singapore but endemic to tropical montane regions in highland Latin America, Asia, and beyond—areas normally kept cool and humid by elevation, cloud, and fog. The refreshingly cool, moist air—first dehumidified by a hidden desiccant cooling system and then rehumidified through the spray of a towering man-made waterfall and artificial mist—cradles both plants and visitors in luxurious comfort. Invisible sensors, algorithms, and a real-time computing system calculate the conditions necessary to create ideal conditions for these cooler weather plants. Next door, another biodome called Flower Dome features the landscape and fauna of the arid Mediterranean and semiarid subtropical regions. Like Cloud Forest, Flower Dome’s cool, dry atmosphere is contained within a clear-spanning double-glazed gridshell structure that separates the enclosure from the humid tropical climate outside. The glass enclosure lets in sunlight and an expansive view of the sky, giving the visitor an uncanny sense of being outdoors while still being surrounded by artificial weather.

Opened in 2012, Cloud Forest and Flower Dome were publicized as architectural and engineering marvels. Located in Singapore’s renowned waterfront park, Gardens by the Bay, their massive glass and steel enclosures offer visitors a journey through the best of “nature” in the comfort of artificially cooled weather. A visit to these attractions offers a shock to the senses, not only because of their spectacular appearance, but because feeling the dramatic shift in temperature and humidity when one enters these biomes is a visceral experience. Their appeal isn’t just the spectacular flora but the pleasure of ambient immersion. Emerging out of a long history where colonial and state powers sought to modify ambient surroundings to further various capitalist and industrial aims through design, infrastructure, and mediation, the biomes at Gardens by the Bay are an example of Singapore’s fascination with the art of artificial weather.

Sunlight, temperature, and humidity are the life-giving and energetic forces of the biomes; they enable plants’ photosynthesis, respiration, and growth, and affect human behavior by determining how hot or cold, comfortable or uncomfortable we feel. By conditioning air and atmosphere—what Eva Horn calls “the medium of life” (2018, 8)—one seeks to manipulate thermodynamic relations between humidity, temperature, light, and other energetic forces within a system. In the case of the biomes, thermodynamic processes are also media processes. As we shall see, achieving thermodynamic homeostasis in these artificial environments is about the logistical management of dynamic atmospheric conditions through a combination of multiple media systems. Recent work in elemental media studies has called for an expansion of the media concept to include not just technological media (e.g., computers, cinema, television, and so on) but also “our infrastructures of being, the habitats and materials through which we act and are” (Peters 2015, 15). Seawater, air, and fire have become some of the media environments taken up by elemental media scholars in thinking through media as milieu or “habitat, and not just as semiotic inputs into people’s heads” (Peters 2015, 4).[1] The contained climates of the Singapore biomes show us how infrastructures of control and biopower are woven across multiple kinds of elemental, environmental, and technological media processes. For example, the ability of sunlight, heat, and humidity to define space and enable life makes them architectural media that organize and condition behavior. Atelier Ten (the structural engineering company behind Cloud Forest and Flower Dome) designs with elemental media such as light and atmospheric moisture alongside more “traditional” materials such as glass, concrete, and steel to control the thermodynamic state of the glasshouses’ contained weather. When energy (such as solar radiation) passes through a medium (such as air or glass), the energetic state of the system is read by sensing media (such as thermometers, light monitors, hygrometers). Meanwhile, technological media (such as computer systems) perform operations that keep the system in homeostasis by automatically unfurling/retracting shades, activating drip irrigation, and so on. This combination of elemental, infrastructural, sensing, and cybernetic media systems enables cool weather plants to thrive indoors in a hot island city.

These media complexes (of glass, moving air, hygrometers, computers, and so on) are what I refer to as “media architectures”—that is, systems of media and mediation that prefigure, process, and manufacture environments and shape the possibilities of life within them.[2] By “architectures” I refer not only to the built structures of concrete and glass that contain these controlled atmospheres, but also to systems of media and mediation both technological and elemental that design environments for living in. Drawing inspiration from the term “architecting,” which programmers and informational architects use to describe the designing of complex programs for “how humans interact with spaces” (Steenson 2017, 2), “architectures” functions as both a noun (i.e., something built) and, more interestingly, as a verb—as in “to structure” or “to design.” “Media architectures” are thus spaces, infrastructures, and systems where processes of calibration and control are carried out through various apparatuses of elemental, technological, networked, and systems media. More so than “infrastructure” (which is often understood to be operating in the background), “architecture” draws attention to how the spectacle of the built form also functions as part of the complex of recursive control between environment, systems, and subject.

Within the “media architectures” of the biomes lies the technicity of state power. The ways in which mediated space carries out modes of calibration and calculation (of atmosphere, human behavior, rate of plant growth, and so on) serve as an important basis for thinking through how power materially manifests through designed space.[3] I build on recent work by Nicole Starosielski (2021), Melody Jue and Rafico Ruiz (2021), Yuriko Furuhata (2022), and others, who examine what Furuhata (2022, 2) calls “thermostatic desire,” a technophilic desire to posit atmosphere itself as an object of calibration, control, and engineering through various forms of biopower and geopolitical governance. Examining media architectures that manage atmospheric thermodynamics, as well as how atmospheric thermodynamics itself architectures (that is, how it defines space and shapes human and nonhuman behavior), reminds us of how biopower and political economy operate through ambient calculation. By ambient calculation, I refer to the ways in which ambient qualities of heat, light, and humidity are rendered into quantifiable data that is then organized and acted upon through a matrix of hidden sensors, computers, and algorithms that appear to operate “out of thin air.” These systems also make invisible other infrastructures—such as those of waste heat, thermal labor, and other inequalities—that in truth uphold the illusion of modernity as an ambient, thermal condition.

Hence, “media architectures” (as a verb) is a lens into understanding modernity as a process and a practice of (state) design. I argue that the condition of modernity as ambient, atmospheric, and palpably felt on the skin is something that comes about through multiple media processes of calibration and control—processes that come out of distinct intersections in the history of (post)colonial architecture, cybernetic theory, and state capitalism. Whether staging the realm of an organism’s possible behavior through walls and floors or through informational feedback loops, designing systems (living and nonliving, human/plant and machinic) is the premise of the fields of both architecture and cybernetic theory. The case of Gardens by the Bay alerts us to how environmental media studies needs to address both fields to better understand itself as a study of control (and controlled) systems. I examine how precedents to the biomes’ dynamic media environments can be found in the colonial practice of tropical architecture, the history of air-conditioning, and the rise of cybernetics as an intellectual movement in British modernist architecture, among other junctures in the history of elemental design.

Humidity (or the lack thereof) has conceptual valence in this paper and is a means through which I conceptualize modernity as something inhaled and inhabited, calibrated, and calculated. Cooling air is an issue of dehumidification.[4] Air must be “dried” first to reduce its specific latent heat capacity—this is the premise of air-conditioning. How cool air feels has to do with the dew point—the temperature at which air can no longer “hold” water in a gaseous state. The lower the dew point, the less the amount of moisture in the air, and the less hot and humid it feels. As a combination of these dynamic factors—solar radiation, temperature, and dew points, among others—managing humidity indoors has a metabolic dimension that involves careful calibration. Its manipulation is also an expression of power over nature and the possibilities of life. In the “middle” of H2O’s two phase states (gas and liquid), humidity embodies the idea that matter is processual, in between, and in flux—not given states, but prone to entropy, atrophy, and decay—and held in place through deliberate design and forms of mediation—human, environmental, machinic, and architectural. The “thermodynamic imaginary” (Jue and Ruiz 2021, 14) signals how states of matter are “relational, lively force[s]” (Starosielski 2014, 2506). Identifying the phase changes of water (e.g., the melting of icebergs), Janet Walker conceptualizes climate change as “matter out of phase” (2021, 275). Building on recent scholarship on the logistics of temperature control (Starosielski 2021), particularly in colonial and postcolonial contexts (Hobart 2022), I attend to the politics of labor, capital, infrastructure, and built design needed to keep H2O in phase for the creation of ambient modernities.

In part I, I trace genealogies of environmental management and control in colonial and postcolonial Singapore to set up the context in which the biomes came to stand for modernity as an ambient condition. When the Singapore government hired British architecture and engineering firms Grant Associates, Wilkinson Eyre, Atelier Ten, and Atelier One—firms that can trace various lineages to British cybernetic architecture of the 1960s—to work on the Gardens by the Bay project in 2006, the idea that buildings could be “thinking machines” emerged in the design of Cloud Forest and Flower Dome, whose media-sensing environments and “elemental” design I examine in Part II. Part III turns toward thermal inequality and the infrastructures of waste heat. As ambient conditioning became synonymous with postcolonial modernity in tropical Asia, the politics of heat and sweat reveal frictions over a race and class politics of cool.

Part I. The Ambience of Postcolonial Capitalism: Tropical Architecture, Air-Conditioning, and the Making of a “Continuous Interior Modernity”

Singapore’s fascination with thermodynamic manipulation must first be situated within a much larger vision of ambient transformation that was part of the nation’s postindependence development plan under the then prime minister Lee Kuan Yew. Post-1965, urban, vegetal, and atmospheric transformation was part of a drive toward an ambient modernity—that is, a modernity experienced as a sensorial environment pleasing to the eyes, skin, and nose. Lee believed that a cleaned-up, litter-free island state filled with lots of greenery would “signify that Singapore was a well-organized city and hence a good destination for tourists and foreign investments” (National Library Board 2024). Greening the city through managed gardens and green space as “visual and technological performance” is what Joanne Leow (2020a, 874) describes as postcolonial Singapore’s brand of “new Asian tropicality” (2020a, 874).

“Value enhancement” continually justifies the superscale levels of ecological transformation that Singapore has embraced in its pursuit of becoming a “world-class” city. The Gardens by the Bay project was proposed by Singapore’s National Parks Board (NParks) as an iconic green attraction that would extend the city’s financial center and raise the valuation of nearby developments. Bordering the sea at the mouth of the Singapore River, Bay South neighbors the Marina Bay Sands (a casino and luxury resort) and hugs the country’s existing financial district at Raffles Place and Tanjong Pagar. As “logo architecture” (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 19), the Gardens was thought to pay for itself as surrounding government-owned land skyrocketed in value.

The project was premised on extractivism and terraformation. The entire eleven-kilometer waterfront promenade is made of reclaimed land, the newest of which was only completed in the 1990s. The site was, until recent decades, a tidal estuary where the Singapore River met the sea. Finished in 2008, the Marina Barrage transformed this intertidal zone into a freshwater reservoir that would irrigate the conservatories and gardens. Meanwhile, the importation of sand and sediment from neighboring Southeast Asian countries has devastated ecosystems, livelihoods, and economic life in these regions.[5] As reportedly the greatest importer of sand in the world, Singapore has since faced sand bans from Malaysia, Indonesia, and Cambodia as a form of pushback against what William Jamieson has described as Singapore’s form of “extracting sovereignty” (Jamieson 2023). In addition to the sand extraction scandals, Singapore faced international critique that its carbon emissions per capita are among the highest in the world (National Climate Change Secretariat Singapore 2024).

Facing such criticism, Gardens by the Bay was made to improve Singapore’s “reputation as a tropical garden nation and responsible global citizen” (W. K. Tan 2012, 9). The design brief for the project demanded that the carbon emissions of the conservatories not exceed those of a commercial complex with the same footprint and height (a rather low bar to clear). Mayee Wong and Jerrine Tan describe how “aesthetic urban futures” (Wong 2022) are produced through eco-technological urbanism and “cyberpunk futurism” (J. Tan 2020), respectively. That Singapore finds this vision of a carbon-neutral futurity in megastructures of atmospheric transformation is also evidenced in the city-state’s ambitious plans to rework the world’s air by sinking excess atmospheric carbon into the ocean by building the planet’s largest ocean carbon dioxide removal (OCDR) facility by 2025 (E. Koh 2024).

What the glass domes of Cloud Forest and Flower Dome sought to create is what Wilkinson Eyre Architects (the architectural firm behind the design of the biomes) describes as a “continuous interior modernity,” a condition of modernity made palpable through immersion in cooled controlled atmospheres contained within towering canopies of glass and steel (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 23). Atmospheric transformation is an essential aspect of creating the ambient conditions of Singapore’s efforts toward “becoming Global Asia”—a term Cheryl Naruse mobilizes to describe the Singapore government’s vision of making Singapore “an alluring Asian setting for capitalist flourishing” (2023, 4). Breath, in the cool, moist air of the Cloud Forest megastructure, is a “form of instant transport” taking the visitor not only outside of Singapore but also, as Eng-Beng Lim puts it, toward futurity (Lim 2016) and “a bigger sense of possibility” (Lim 2014, 449). Resonating quite literally with Peter Sloterdijk’s notion of the “world interior of capital” (2013), the biomes speak to how globalization is a process of the interiorization of the world—not the erasure of an “outside” but rather the absorption of the world into a carefully calculated interior. For Sloterdijk, the crystal palace in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1963) represented globalization as an “extended macro-interior,” an exclusive “comfort structure with the aid of all the appropriate kinds of media and material transactions” (2013, 358). Whereas the original Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, was built for the Great Exhibition of 1851 to showcase the technological prowess of Victorian England and the Industrial Revolution, the Singapore biomes showcase a simulacrum of nature and mastery over climate as a symbol of the technological and financial ascendancy of Global Asia over 150 years later. Walking through Cloud Forest—a signifier of Singapore’s brand of ambient modernity—one literally inhales and interiorizes atmospheres of global capital in an environment artificially sustained through multiple media apparatuses.

How did cooled air become associated with modernity, particularly in the (post)colonial tropics? Tied to notions of health, hygiene, temperament, mental acuity, and economic productivity, controlling humidity and temperature has long been the prerogative of architecture in the tropics. For an island situated 1.35°N of the equator, temperature, as scholars such as Hi’ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart (2022) and Jen Rose Smith (2021, 159) remind us, is a political thing whose control and manipulation are entangled with long histories of colonization. Architecture historian Chang Jiat Hwee (2016a, 2016b) traces how seemingly apolitical environmental elements such as shade, natural lighting, and ventilation—all fundamental tenets of tropical architecture—are inseparable from colonial regimes of technoscientific knowledge and ideology. The idea that climate could be rendered as information can also trace its lineage to climate studies performed in colonial Britain’s tropical territories (Chang 2016a, 104–6). The information helped to protect white health and determine the design elements of tropical barracks and hospitals (Chang 2016a, 97–99). Passive cooling (such as through sun-shading) for the biomes was partly inspired by colonial tropical architecture—in turn influenced by indigenous Malay and other vernacular designs (Ferng et al. 2020, 250–62).

The arrival of air-conditioning in the tropics steered the relationship between design and environment “from climate responsive architecture to[ward] architectures of climate control” (Chang 2016a, 246). Air-conditioning was introduced to Singapore in the late 1930s, though it blossomed as the island colony moved toward independence in 1965. Mechanically cooled office buildings such as the Asia Insurance Building and MacDonald House, which welcomed full air-conditioning in 1955 and 1949, respectively, were a “symbol of confidence in Singapore’s future” (Chang and Winter 2015, 100). Taking on the developmentalist rhetoric of the postcolonial era, newly independent tropical nations saw air-conditioning as an important factor in the rise of the modern nation and an opportunity to rise above climate determinism (Chang and Winter 2015, 100). Thanks to air-conditioning, believed Lee Kuan Yew, tropical nations would no longer lag behind so-called advanced civilizations from cooler climates:

[Air-conditioning] changed the nature of civilization by making development possible in the tropics. Without air-conditioning, you can work only in the cool early-morning hours or at dusk. The first thing I did upon becoming prime minister was to install air conditioners in buildings where the civil service worked. This was the key to public efficiency. (2009, 120)

Lee’s statement not only reveals how colonial ideas concerning climate, civilization, and modernity lingered well into postcolonial state developmentalism, it also indicates how imperative environmental control was to Lee’s ideas of white-collar work and socioeconomic progress. Without it, “Singaporeans would be somnambular zombies for a significant part of every afternoon,” as Chua Beng Huat (2008, 1) quips.

Just as air-conditioning was deemed critical for a strong civil service in the postindependence years, controlling heat and humidity remains a key element of Singapore’s transition toward becoming a financial hub and knowledge-driven economy in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries. White-collar industries such as the financial, IT, biotech, and other business sectors needed climate-controlled buildings to house their staff, equipment, and offices. As more and more spaces in Singapore became air-conditioned—from government offices in the 1960s to shopping complexes in the 1970s and eventually to bus bays, walkways, and practically every form of built space, climate control and national developmentalism were entangled in an “irreversible thermal modernity” where cooled air became synonymous with urban redevelopment and modern life in the tropics (Chang and Winter 2015, 108).

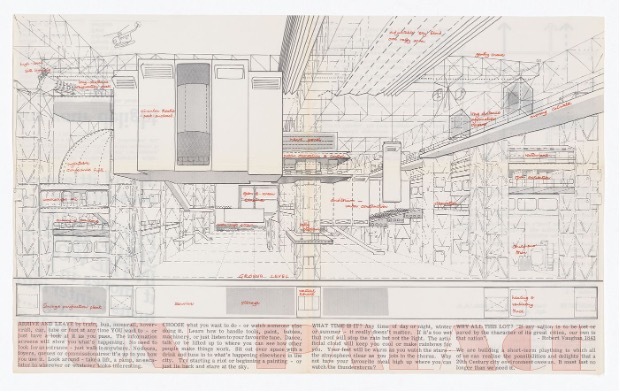

Architecturally, the proliferation of glass-enclosed spaces speaks to the “perennial modern condition” of climate-controlled interiors—the airports, megamalls, and atriums of modern life (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 23). Glass buildings aestheticize an uninterrupted ambient modernity—a visual seamlessness between interior and exterior, yet one where interior space is shielded from the brutal outdoor heat. The idea of modernity as an ambient experience that could be created through glass-domed buildings was also a modernist architectural fantasy with a lineage that included Bruno Taut’s Glass Pavilion (a prismatic glass-domed structure built for the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne, Germany) and Buckminster Fuller’s mid-twentieth-century geodesic domes, which enclosed large volumes of space within a sphere. Both of these designs manipulated elements such as light and atmosphere through glass to render modernity as an embodied experience for the visitor. Taut’s structure channeled sunlight through a double-glass dome, while Fuller’s domes created climate-regulated environments under a large spherical structure that enabled circulating air to heat and cool naturally.

From inside the biomes, one gazes through endless facets of clear glass at Singapore’s financial district. The skyscrapers and iconic buildings of Singapore’s southern coastline (such as Marina Bay Sands and the Esplanade) appear as if they are an extension of the ambient modernity experienced within the biomes. This effect was achieved by strategically obscuring key structural elements of the building. The building envelope consists of two layers: encasing steel ribs that buttress a glass gridshell that acts like a curvilinear eggshell around the cooled interiors. The double-glazed glass lets as much light in as possible without overheating the interiors. Placing the structural steel ribs on the outside of the building offers better structural support while also being less noticeable from the inside, allowing visitors “to read the gridshell rather than the ribs” (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 53). From the inside, the glass shell is “read as a complete system” (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 23), creating the expression of an ambient modernity that continues between interior and exterior. From the outside, however, the steel ribbing that holds up the glass panels acts as an iconic design feature, adding visual interest to the landscape and producing the recognizable logo architecture that puts Singapore on the map as a world city. The result, when one approaches and then enters the conservatories, is an uncanny experience of infrastructure melting into ambience.

To uphold the illusion, certain aspects of the biomes’ design, infrastructure, and upkeep are spectacularized while others are made to recede into the background. Design elements such as the gridshell and the steel ribs are made spectacular. On the other hand, other building infrastructures including the energy-hungry desiccant cooling system, the waste heat disposal system, and a human labor network based on low-wage migrant workers are hidden under the floors, disguised, situated off-site or after hours. These are the background infrastructures—human and machinic—that are too ugly, too messy, too exploitative, or too reminiscent of industrial-era dystopias to be publicly displayed. “Continuous interior modernity” in the Global Asian city involves pervasive mechanisms of state power over the very conditions of breath and sweat in which we labor and languish (a critique I address in Section III).

In the first few decades of the twenty-first century, Singapore’s vision of ambient modernity has become deeply entangled with its “Smart Nation Journey”—a national initiative that “leverages sensors and data to better drive public agencies’ operational efficiency” (Gardens by the Bay 2020, 2). Launched in 2014, this data-utopianist vision for Singapore describes the digitization, datafication, and implementation of artificial intelligence and data infrastructure in every aspect of life. Here, “environment” is conceptualized as a deeply sensory surround, a neural network that perceives, calculates, responds, learns, and predicts. Sensors and remote monitoring relay real-time information about everything from air pollution to traffic congestion. By aggregating, individualizing, and acting upon the data of populations through real-time calculation, big data analytics enable better biopolitical control and a means to “open new frontiers of growth” (Singapore Smart Nation Digital Government Office 2019, 12)—what Orit Halpern and Robert Mitchell describe as “the smartness mandate” (Halpern and Mitchell 2022, 3). Part of the Smart Nation initiative, the “Smart Gardens” project at Gardens by the Bay implemented a system of network sensors, automated data collection technologies, artificial intelligence, and machine learning technologies to monitor the environmental parameters affecting plants such as temperature, light quality, humidity, soil moisture, and salinity (which also reduced labor costs) (Gardens by the Bay 2020, 2).

Smart Nation is indicative of how “cybernetic” ideas have become so completely absorbed into various “commonsense” forms of neoliberal market capitalism (Tiqqun 2020, 24) that they have become fundamental in managing modern life in the global Asian tropics. Media processes such as “information storage, processing, and transmission (as well as associated concepts such as “steering” and “programming”) [… are …] instrumentalized to both model and direct the functional entirety of […] life” (Franklin 2015, 19; 2021, 6). “Dashboard governance” (2021, 16), as Shannon Mattern puts it, “frames the messiness of urban life as programmable and subject to rational order” (2021, 62), even as it leaves out urban subjects and dynamics that do not compute. In the next section, I trace certain design elements of the biomes—particularly the relationship between machine, mediation, and environmental design—to theories of cybernetic architecture in 1960s Britain.

Part II. The Computer and the Gridshell

“The plants are your client,” the architects were told (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 45). The design brief developed by NParks posed the considerable challenge of creating a glasshouse habitat for cooler-weather plant species to thrive in the most energy-efficient way possible. The problem was that glasshouses were historically colonial apparatuses of climate control, designed to maximize light and solar gain to keep economically and scientifically valuable plant species from the tropics alive during cold northern winters. Cloud Forest and Flower Dome demanded the opposite: not only did plants have to be sheltered from hot and humid weather, but the buildings also had to be responsive to the frequently fluctuating light levels at the equator—too bright on a cloudless midday but also too gloomy during rainy seasons. Plants needed a peak illuminance level of 45,000 lux to grow, but too much solar radiation would place an unnecessary load on the cooling system (Bellew and Davey 2012, 6). Moreover, internal conditions had to mimic the plants’ natural habitats—temperatures and humidity had to vary within the day, and from month to month. These included “ignition” periods once every third month where nighttime temperatures would be reduced to trigger blooming cycles. The reversal of weather-host dynamics in the tropics called for the imagination of architecture as a dynamic yet self-contained system.

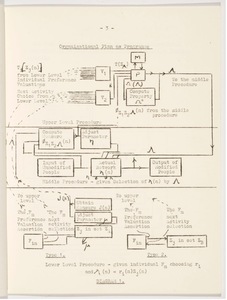

Since its proliferation post–Second World War, the field of cybernetics has introduced systems thinking and discourses of recursivity into urban planning and architectural design.[6] Coined from the Greek term for “steersman,” or kybernetes, cybernetics can be considered “the art of piloting (or controlling) systems, with etymological reference to governing” (Torisson 2017, 4). As “a network model for systems” (Galloway 2014, 113), perhaps its central tenet is recursivity of information—how the system’s (or organism’s) output returns as feedback input enabling a process of self-correction. The system “continuously adjusts itself in response to dynamic and unpredictable conditions by anticipating future behavioral patterns on the basis of feedback information from prior actions” (Mathews 2006, 41). Consequently, a dynamic and self-regulating system with “predictive” power emerges.

Cybernetic theory would influence some of the leading architecture, design, and engineering powerhouses in the United Kingdom today—companies that would be hired by the Singapore government to work on the Gardens by the Bay project. These included Grant Associates (master planner and landscape architect), Wilkinson Eyre Architects (lead design for cooled conservatories and other associated infrastructure), Atelier One (environmental engineer), and Atelier Ten (structural engineer). These companies, particularly Atelier Ten, were known for their environmental design and engineering projects. Their approach to environmental engineering can be traced to the convergence between cybernetic thought and a systems approach to environment in 1960s and '70s British architecture (Finch 2015, 11). For instance, Patrick Bellew, Atelier Ten’s founding partner, studied at the University of Bath under Sir Edmund Happold, a structural engineer known for his contribution to British high-tech architecture—a late modern architectural philosophy exemplifying the praxis of the building as machine.[7] One of Happold’s projects was the Eden Project in Cornwall, whose rainforest and Mediterranean biomes were a major influence for Singapore’s biomes. Chris Wilkinson, cofounder of Wilkinson Eyre Architects, also worked with the big names in British hi-tech architecture, such as Norman Foster, Michael Hopkins, and Richard Rogers.

Scholars have traced the lineage of cybernetic theory in architecture, approaching architecture as an assemblage involved in the production and control of information and its distribution (Martin 2003; Halpern 2014; Steenson 2017; Furuhata 2017; Kousoulas and Perera 2021; Torisson 2017). What these and other writings indicate is that architecture can itself function as a media environment, capable of both receiving, transmitting, and acting upon information in responsive, recursive, and predictive ways. Halpern describes how, by the 1970s, architecture was being envisioned as a new “machine”—“a computational and artificially intelligent network composed of intimate feedback loops between designers, users, and computers” (2014, 10). Buildings were imaged as processes—intelligent and integrated communications systems that could sense and respond to sensory input from the environment. “With cybernetics,” Molly Steenson writes, “architecture became a mechanism of information exchange” (2017, 18).

For all that to happen, cybernetic architecture was first premised upon turning environments into flows of information (Hayles 1999, 2, 8). By treating elemental and behavioral phenomena—like temperature, humidity, solar radiation, plant growth, human behavior, and so on—as information, cybernetic architecture makes such behavior parsable to computational calculation, machinic processing, and system reflexivity. Two key elements of cybernetic architecture would find their way into the design elements of the biomes at Gardens by the Bay. First, elemental conditions had to be converted into information, and second, this information had to become part of a reflexive feedback loop that enabled the buildings to achieve dynamic homeostasis. I examine both these processes in the rest of this section.

Cybernetic architecture, elemental design

One of the earliest to theorize the convergence between cybernetics and architecture in his 1969 essay, “The Architectural Relevance of Cybernetics,” British cybernetician Gordon Pask describes architects as “first and foremost system designers” (1969, 494). Describing what he dubs “the cybernetic theory of architecture,” Pask finds within cybernetic thinking a metalanguage for understanding that vital connection between designed environments and control. As he writes, “design is control of control” and “architecture acts as a social control” (Pask 1969, 495, 496). A “machine for living in” and thinking with, a building was “an environment with which the inhabitant cooperates and in which he can externalize his mental processes” (Pask 1969, 496). The building itself would take on calculation and memory work, relieving its inhabitant of such burdens. Here was a kind of architecture premised in cybernetic notions of dynamic communication, recursivity, and self-regulation, a “giant learning machine” (Lobsinger 2000, 126).

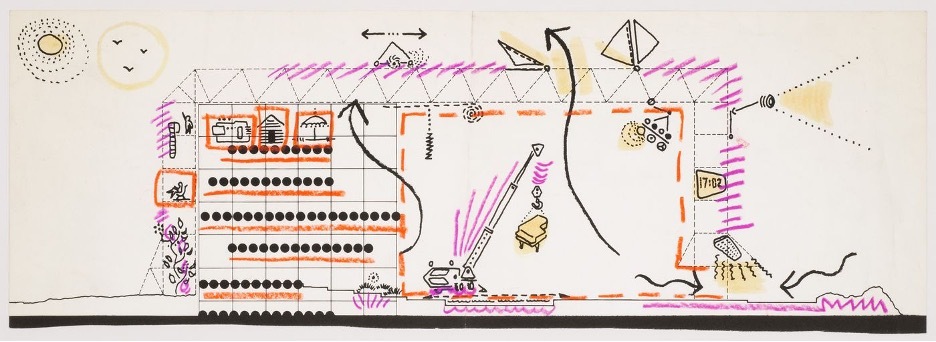

Inspired by Gaudí’s Park Güell, cybernetic architecture is an ecology where the “inside” inhabitant is in dialogue with the “environment” through the built interface (Pask 1969, 496). The Fun Palace project (1961–64), designed by theater veteran Joan Littlewood and architect Cedric Price in collaboration with Pask (but never actually constructed), is an often-cited example of a cybernetically responsive space that proposed to adapt to its users as they interacted with the building (Mathews 2006, 43). The Fun Palace had movable plastic facades, cranes that could reposition rooms, and a computer control system that would reconfigure space according to user behavior (Herdt 2021, 54). Telecommunications technologies and closed-circuit TV would enable participants to observe and react to each other in real time. Roy Ascott’s “Pillar of Information” was an electronic database able to track, visualize, and display data about how users used space, and suggest multiple pathways for future use (Matthews 2006, 45). Here was a kind of architecture premised in cybernetic notions of dynamic communication, recursivity, and self-regulation, a “giant learning machine” (Lobsinger 2000, 126).

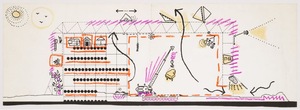

Designing with the elements was fundamental to buildings being understood as environmental systems (both systems within environments as well as environments within systems). Pask fancied himself an “anti-architect” designing what he called “anti-buildings” using elemental media such as “warm air, electric light, ultra-sonic waves, the sky, the prevailing weather, the ships across the river as well as plastic, glass and alloys and other conventional preventive materials” to enclose space.[8] As the design engineers for the Singapore biomes, Atelier Ten mobilized similar principles of “invisible architecture” for which “air, heat, light and sound” are the key planks (Bellew 2015, 11). Atelier Ten saw themselves as not only designing environments but also designing with ambient, atmospheric, and elemental media. Elemental conditions such as sunlight, moisture, and circulating cold air were as fundamental to the building as were walls, roofs, and floors. While they used materials such as glass, concrete, and steel in their building elements, what they were really designing with were the elements.

Designing with elemental media was not new. Prior to the ubiquity of air-conditioning, for example, both tropical architecture as well as modernist approaches to climatic design relied on architectural (rather than mechanical) means of manipulating environmental conditions (Barber 2020, 9) with techniques such as shading to cool interiors. Making thermal control the purview of design (rather than ugly, clunky HVAC units) elevated the impression of continuous interior modernity, which melded well with the aesthetics of the Gardens by the Bay project. By returning to these principles of invisible architecture, the cooled conditions within the biomes would appear “natural” and seamless to the eye under a sky of clear glass.

Designing with the elements also met the low-carbon aspirations for the project. A building envelope that modulated interior conditions through “passive means before resorting to [energy hungry] active systems” (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 54) would drastically reduce the reliance on energy for cooling.[9] For that they had to consider the behavior of air, sunlight, and solar radiation and their effects on brightness, heat, and humidity inside the biomes. For instance, the tilted geometry of the conservatories reduced the surface area exposed to the sun while their bulbous volume enabled the flow and stratification of air within. Called displacement ventilation, this allowed cool air to settle in pockets around the walkways and planting displays at the lower inhabited levels while hot air rose upward toward the top of the domed structure, where it would be discharged or recycled.

Articulated in the biomes’ design was the inseparability of environment, organism, and machine. A distinguishing characteristic of cybernetics was its “universalism” as a science that could be applied to both machines and living organisms (Bowker 1993, 110). Oftentimes, systems designs are inspired by nature—an approach known as biomimicry, where buildings mimic how natural systems achieve homeostatic self-regulation through structural design. For instance, Wilkinson Eyre based the tall, open dome structure of the “mountain” in Cloud Forest on the lacelike filigree “bridal veil” of the stinkhorn mushroom—the idea was that open cells would permit airflow and act as a huge air displacement unit that would cool the space (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 77). Aspects of Atelier Ten’s techniques of “invisible architecture”—such as the airflow promoted by landscape design and displacement ventilation—approximate African desert termites’ nests. As environmental architecture and engineering in the 2000s turned toward designing with ambient media such as wind, heat, and light as a conscious move toward sustainable and energy-efficient buildings, these climate-responsive architectural forms aspired toward functioning as organic and organismic systems themselves.

Ambient calculation was made possible through computer software systems. As Pask predicted (1969, 496), computer-assisted design would be necessary to understand otherwise hard-to-see relationships between elemental conditions, thermodynamic behavior, and building design as entire environmental systems. Wilkinson Eyre used CAD (computer-aided design) modeling software to explore technical ideas such as geometry, structure, and cladding and how they would affect air circulation, daylight entry, and energy use (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 39). Atelier Ten developed bespoke software to evaluate daylight levels and heat gains throughout the year (Atelier Ten 2015, 135). 3D computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models systematically studied heat flows to analyze and optimize the airflow within the building structure. Concurrent improvements in computational power meant that these models could work in a “predictive” way, helping to direct design rather than merely assessing completed designs (Atelier Ten 2015, 131).

Sensing media, systems engineering

While passive design went a long way toward keeping light, heat, and humidity within large tolerance levels, that alone was insufficient to create the dynamic variability that the plants required or to help the building achieve homeostasis. As Pask had said about human interaction, the relationship of plant life to various ambient conditions (light, heat, moisture) is a complex interaction “that can only be overcome by cybernetic thinking” (Pask 1969, 494). Pask envisioned this reactive environment to be one where “a computer controls the visual and tactile properties of environmental materials” and these environmental materials would in turn “contain sensors [that] return messages to the computer at several levels of generality” (Pask 1969, 496). The solution was to design the building as a sensing, responsive, and self-regulating system reactive to slight changes in light levels, temperature, and humidity.

The biomes were designed to function as “information-rich” systems whose exterior shell and interior surfaces were outfitted with sensing and telemetric technologies that would respond to dynamic conditions. Environmental measuring stations—footlong brown boxes on a raised pole—are dotted throughout the planting beds. Sensing media—thermometers, hygrometers, infrared sensors—transform ambient conditions into data that can be read, calibrated, and acted upon by centralized computing systems programmed to create the perfect simulation of a plant’s natural habitats (Bellew and Davey 2012, 93). Sensor technologies, as Jennifer Gabrys (2016) discusses, enable environments to become programmable while also enabling computation to become environmental. They convert complex environmental conditions into computational data that can be read, interpreted, and then acted upon by a self-learning system. For instance, light sensors read the amount of light that specific planting beds are receiving. These sensors are connected to the building management system, run by an automated programmable logic control (PLC). Whenever the light sensors sense direct sunlight above the optimum, the system automatically activates a grid of 419 shading panels that unfurl over the affected zones in the domes (Nadarajan 2013, 78). The PLC panel is a real-time industrial computer that uses “an intelligent self-learning algorithm” that adjusts the shades to match the conditions (Bellew and Davey 2012, 56). Armed with rain and wind sensors, the exterior building envelope is also a sensing “skin” connected directly to the PLC panels, feeding the system with data about incoming storms. According to Woh Hup, the construction company building the structures, “so sensitive and intelligent was the system that a few drops of rain would send the panels curling back into the protective cover of their housing components even if the sun was still shining brightly” (Nadarajan 2013, 78).

Under ferns and ficus trees, the conservatories are serviced by a vast network of hidden infrastructure (such as underground tunnels housing pipes, cabling, exhaust chimneys, service access, and other back-of-house elements that run the cooling system). Whereas the architectural elements of climate-regulating design—the glass domes, the towering waterfall that mists the air, the undulating landscape that allows hot and cool air to move and stratify—are elevated to the level of capital-producing spectacle (in line with the aesthetics of a seamless ambient modernity), the biomes’ mechanical systems are “invisible,” self-functioning, internally communicating black boxes that operate quietly under the hood.

The convergence between cybernetic architecture and systems engineering can be traced to the 1970s, when “cybernetics gave way to ecology as a concept to describe the relationship between humans and the natural environment” (Herdt 2021, 45). In this view, scientists, architects, and planners understood the world as made up of complex systems and processes that were connected on a planetary level. With the 1972 United Nations declaration on environmental policy and the climate crisis, rethinking buildings as complex energy systems that had to be made efficient and sustainable became a pressing issue. British cybernetic modernists would develop a systems approach toward designing space as living ecologies and as ecologies for living in. Jim Eyre, founding partner of Wilkinson Eyre Architects, was introduced to the idea of “designing with climate” as an architecture student in the late 1970s (Atelier Ten 2015, 134). By the 1990s, the architectural and engineering fields were concerned with how “to make good weather” inside buildings while reducing energy demands and using systems of environmental feedback in climate-regulating design (Bellew 2015, 10).

The biomes’ diffusion cooling system is a form of systems engineering that involves the manipulation of humidity in a complex system of energy transfer. It is also a system that is largely hidden from sight, where the main generators, turbines, and chillers are located below ground and/or in a separate service building inaccessible to the public. Instead of traditional air-conditioning, the biomes rely on desiccant conditioning, which uses a chemical process to alter humidity. Desiccant conditioning removes moisture from air to reduce its latent heat capacity, and thereby its temperature—a less energy-intensive process than traditional air-conditioning. As warm, moist air is passed through the liquid desiccant (Kathene, a form of lithium chloride solution), it sheds its moisture—moisture that must again be removed from the desiccant by refrigerator units. To power the desiccant conditioning system without drawing from the electrical mains, hot air is collected from the top of the biomes, and energy is generated from a biomass boiler. The downstream hot water produced by the turbine is also used to drive absorption chillers that generate the cold water for the biomes’ floor cooling pipes, as well as supply the heat that drives out moisture from the desiccant regenerator units. I describe the building’s cooling system at length as it indicates how the entire system of climate control is premised on the careful calibration of the phase states and heat capacities of water and air—that is, humidity.

In the biomes, one breathes in invisibly controlled atmospheres that have been highly mediated through sensing technologies, computational systems, and thermodynamic infrastructure. These infrastructures of control are diffused into design such that they are inhabited as ambience, milieu, and surrounds. Pask’s vision of a reactive and adaptive environment that does all the thinking—a “machine for living in” (1969, 496) that performs all the calculations and “mental processes” needed to support life—is, to a degree, realized in these conservatories. Whereas the Fun Palace project was designed for the working classes as a space for democratic pleasure and participation intended to go against top-down, centralized forms of town planning, education, and governance, systems-based architecture in the Singapore biomes would ironically function to showcase a culture of state control in the creation of a leisure attraction for those who can afford the price of a ticket.

Part III. Where Does All the Heat Go? Thermal Inequalities of Drying Air

Surplus heat from the absorption chiller system that cools the conservatories is released into the environment through carefully landscaped towers called Supertrees. Ranging in height from twenty-five to fifty meters, the outsides of these iconic funnel-shaped columns—whose tops resemble (barren) tree branches that light up at night—are adorned with bromeliads, ferns, orchids, and flowering climbers that conceal the thermo-regulating chimneys that keep the conservatories lush and cool.[10] The Supertrees disguise what are effectively heat dumps. The silver cluster of Supertrees at the edge of Dragonfly Lake discharge “hot and ‘dirty’ air” (Bellew and Davey 2012, 22) from the dehumidification process into the lower atmosphere a mere thirty meters above ground. Despite assurances that the flue gases are “invisible, harmless, and non-toxic” (Bellew and Davey 2012, 98), the waste heat they release is an environmental externality. Grant Associates described how the landscape surrounding the biomes acts as an environmental shock absorber—taking in and dissipating heat. Where does all the heat go? And whom does this effect of heat dumping most impact?

Rising temperatures are a chronic and escalating problem in Singapore. The island is warming up twice as fast as the rest of the world, at 0.25°C per decade (F. Koh 2023). Caused by a combination of background global warming and urbanization, the urban heat island effect in Singapore has been intensely felt in the past few decades. Urban structures trap and radiate heat, explaining why temperature differences vary up to 7°C between urban and less built-up regions of Singapore (SG101 2022). Singapore’s response to the rising temperatures created by overbuilding has been to build more indoor air-conditioned spaces. But air-conditioning is a selfish technology. While they cool interiors, air-conditioning units dump hot, moist air outside of buildings, resulting in heightened surrounding temperatures (Salamanca et al. 2014; Yuan et al. 2022). And while Singapore pursued air-conditioning to pivot its economy toward white-collar industries, low-wage work continues to be carried out by racialized, migrant labor in hot kitchens, outdoor construction sites, and industrial zones. Cherian George describes the nanny state’s form of pervasive control via the metaphor of an “Air-Conditioned Nation” (George 2020, 34). Just as central control is a feature of air-conditioning, who does and who does not get to labor in sweat is a question of biopolitical control at multiple levels of urban, political, cultural, and social planning.

As this article has sought to demonstrate, capitalist modernity in the postcolonial tropics is an ambient condition. But in being an ambient condition, modernity is also a state of embodiment where feeling too hot, too humid, and too sweaty excludes the subject from being a global player in a world of “temperate normativity” (Smith 2021, 159). Where myriad forms of “smart” design and cybernetic architecture insulate/regulate/integrate the privileged state subject within various ideal atmospheric conditions, heat and sweat are where the frictions and inequalities of global Asia are endured.

As climates warm, urbanization soars, and air conditioners run full blast, the effects of thermal inequality are increasingly shouldered by the global poor. In the case of wealthy Asian tropical countries like Singapore, the sort of work that demands prolonged exposure to intense heat is outsourced to racialized Global South bodies. In 2023, there were 441,100 migrant workers working in the construction, marine shipyard, and process sectors (Singapore Ministry of Manpower 2024). Without sufficient legal protections, migrant workers in construction industries are continually exposed to heat stress in overcrowded prefabricated dormitories after work hours (Ferng 2020) and excluded from air-conditioned shopping malls and libraries (Chen 2022; Business Times 2024). Such thermal inequity is the product of the country’s economic imperative to keep the costs of foreign labor down. As Waqas Butt describes, waste work is “an infrastructure of urban life” (2023, 23) making capitalist flourishing possible. “Thermopower,” as Starosielski writes, “operates as a form of biopower, a means of administering and regulating life” (2021, 7).

The thermal conditions of work in the region have a long history that goes back to plantation economies and colonial extractivism.[11] British colonists deemed themselves too ill adapted to tropical heat to work manual jobs; they believed that “darker” races were better suited to labor in hot climates. The rubber industry was predicated on the work of indentured laborers who came from South Asia to work on Malayan plantations. These colonial-era transoceanic networks of labor recruitment and financing have endured in today’s logistics of migrant labor contracting.[12] Singapore’s megastructures of climate control today are made possible by generations of burnt-out and heat-exhausted bodies. Wilkinson Eyre’s British on-site project consultants were reminded of these hierarchies by their Singaporean colleagues: “Only the workers wear high-viz vests, and you don’t want to look like a worker” (Wilkinson Eyre Architects 2013, 102).

On my last visit to Flower Dome, in August 2023, I notice two figures, high overhead, repairing the retractable screens on the outside of the glass dome. Their work goes unnoticed by visitors on the inside—partly because they are so high up, but largely because the glass dome trains our vision to either look through it at the scenery outside or to keep our attention immersed within the internal space. The workers blend in with the other operational systems that quietly hum underground or behind discreetly placed panels. They must be sweltering in their protective gear and high-visibility vests. The scene is a reminder of what one might have witnessed some fifteen years prior during the construction of the conservatories. Because the buildings were designed to displace hot air upward, temperatures at the top of Cloud Forest could reach 50°C. Workers would be up there for several hours at a time, doing physically demanding labor in the unbearable heat.

Making artificial atmospheres is the stuff of states, buildings, computers, and bodies whose systems of thermodynamic calculation and humidity control turn modernity into an ambience that some enjoy while others endure. In the Singapore biomes, cooled air is the materialized ideologies of the media architectures that structure relations between people, things, and environments. The combination of elemental design, computational processing, sensing systems, and invisible thermal labor transforms power into the ubiquity of ambient immersion—quite literally the atmosphere that we breathe.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Connaught New Researcher Award at the University of Toronto. Two anonymous reviewers have provided generous and productive feedback. Key concepts in this paper were developed in collaboration with the Media Architectures Research Group: Peter Bloom, Christina Vagt, Weihong Bao, Reinhold Martin, Jeremy Packer, and Bree Lohman. Appreciation goes out to the workshop participants at the Strata of the Asia Pacific Workshop (October 25–26, 2024); thanks especially to Yuriko Furuhata, Weixian Pan, Shaoling Ma, Kimberly Chung, and Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol, whose astute comments helped refine the paper in the final stages of its writing. Chang Jiat Hwee and Gerald Sim have contributed to the formulation of this paper through early conversations. Sunny Xiang and Cheryl Naruse were wonderful readers of an early draft. Thanks also to Stephen Schwartz for his diligent edits.

For a philosophy of environmental mediation and the elementality of media, see John Durham Peters’s The Marvelous Clouds (2015). For a study of media through seawater, see Melody Jue’s Wild Blue Media.

The term “media architectures” was developed in collaboration with members of the Media Architectures Working Group—particularly Christina Vagt, Peter Bloom, Weihong Bao, Reinhold Martin, Jeremy Packer, and Bree Lohman.

For Siegert, “cultural techniques” are the basic, material, and operational practices that precede symbolic meaning and prefigure media concepts. For example, “doors […] are a fundamental cultural technique, given that the operation of opening and closing them processes and renders visible the distinction between inside and outside” (Siegert 2015, 13). For more on “cultural techniques,” see Winthrop-Young (2013) and Siegert (2015).

Modern HVAC systems use evaporator coils to cool air, a process that removes moisture from the air by causing it to condense—similar to when a cold can of soda begins to sweat on a hot day.

Filmmaker Kalyanee Man’s Lost World (2018) examines the effects of Singapore’s sand extractivism on the estuaries of Koh Sraloa, Cambodia. See also Leow (2020b, 2024).

In 1948, Norbert Wiener devised the foundation for a new theory of systems, information, and communication, known as “cybernetics.” See Wiener, Hill, and Mitter (2019).

Often showcased through a smooth, impervious skin (such as glass), buildings in the high-tech style were interested in revealing—rather than hiding—the various systems and networks (e.g., pipework, air-conditioning, electrical wiring, structural engineering elements, etc.) that create habitable space. Also characteristic of this style was “system-building,” which favored component-based, lightweight, interchangeable, and easily transportable building materials that made for modularity and flexible floor plans that—as inspired by the cybernetically attuned Fun Palace—could evolve with new uses.

Cedric Price, “Notes on the Fun Palace Project,” 1961–1974, DR1995:0188:535, Cedric Price Archives, Canadian Center for Architecture, Montreal, https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/search/details/collection/object/400582.

In architectural parlance, the “envelope” refers to the physical barrier between the interior and the exterior of a building—that which maintains and separates climate-controlled interiors from the external environment (e.g., roofs, walls, floors, and doors).

Aside from releasing exhaust air, the Supertrees also collect solar power and rainwater.

On the association between race and plantation labor in the tropics, see Ikuko Asaka’s Tropical Freedom (2017).

On the colonial continuities regarding the migration of Tamil labor to Singapore and Malaya, see Yeoh, Wee, and Lam (2022, xvii).

_and_flower_dome_(*right*)._the_external_structural_.jpg)

_with_its_bridal_veil_structure._photo__vinayara.jpg)

._termites_regulate_airflow_within.jpg)

_and_flower_dome_(*right*)._the_external_structural_.jpg)

_with_its_bridal_veil_structure._photo__vinayara.jpg)

._termites_regulate_airflow_within.jpg)