Introduction

Climate change resulting from unchecked fossil fuel use, exacerbated by habitat fragmentation, overpopulation, and sprawl, prompted me to develop The Blued Trees Symphony (2015–present). This project is a transdisciplinary large-scale eco-artwork intended to effect social and ecological change. In 2015, at the invitation of private landowners, I began installing a series of one-third-mile-long musical measures in forested corridors where natural gas pipelines or pipeline expansion projects were proposed. GPS-located individual trees in each measure were mapped as “tree-notes,” in an aerial score. Tree-notes were identified in advance using aerial satellite mapping and ground-truthing. The measures were transposed and performable by live musicians. Each measure included at least ten tree-notes conceptualized in G major, a key that musicians in the Baroque period, such as Scarlatti and Bach, considered pleasing and stable. Since the intention of the project was to envision continental habitat contiguity, this seemed the obvious choice. The time signature in the score submitted for copyright is unperformable in any conventional sense: thirty-two beats to a measure, and the quarter note gets one beat because it is too rapid. This time signature was intended to indicate that we need to imagine another world if we aspire to protect the one we have. But the melodic refrain can still be sung, performed, and developed.

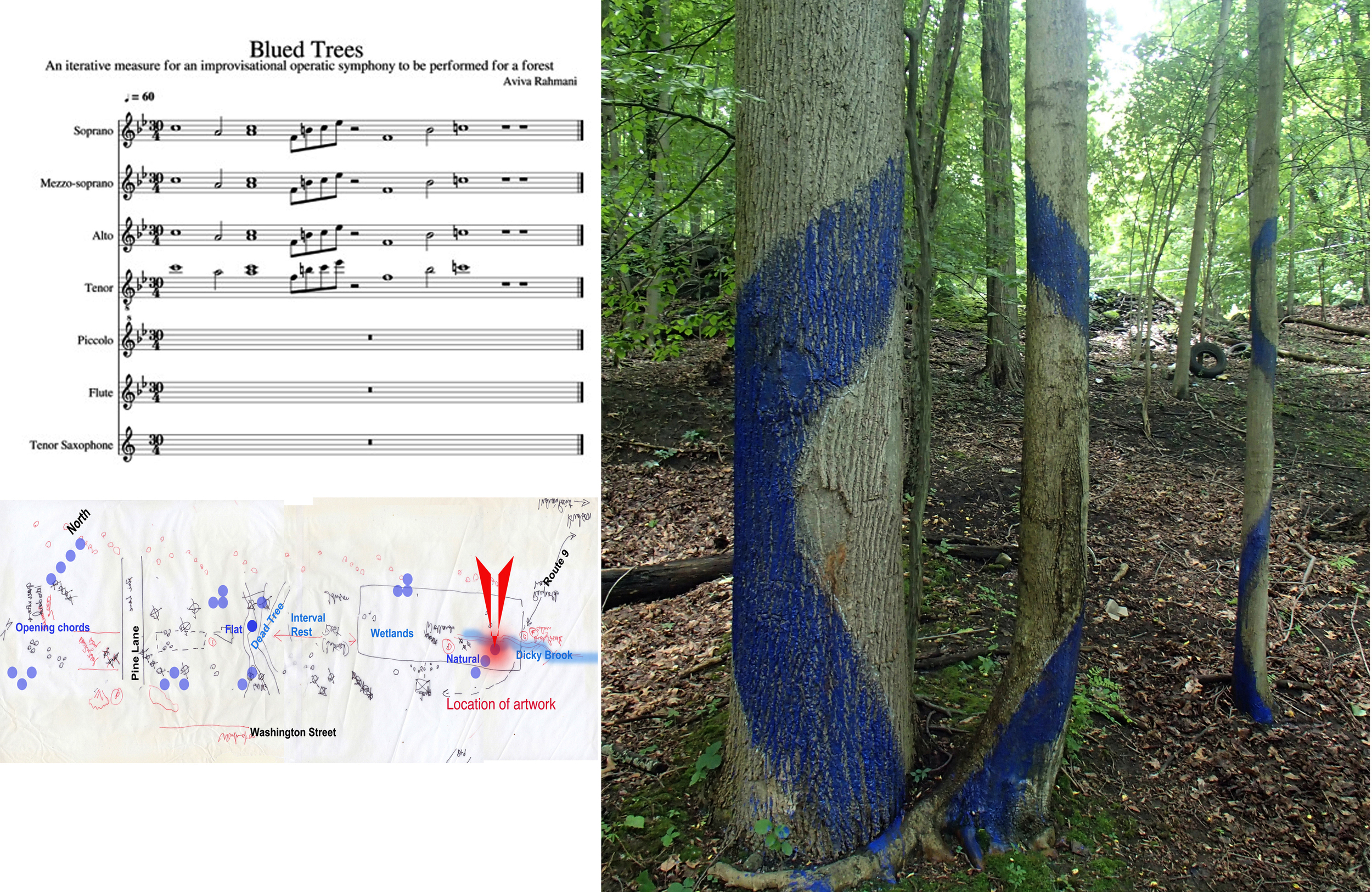

The legal intention was to “harmonize American with European intellectual property laws protecting droit moral, the moral rights of art and extending the law to protect features of ecological significance.”[1] The tree-notes were each marked with a vertical sine wave design. A sine wave indicates the movement of sound in time. The mark, like the impossible time signature, was intended to symbolize an acoustic experience that is multidimensional. The marks were painted—from canopy to roots, including rock formations at the base of the trunk—with a permanent casein of nontoxic ultramarine blue and buttermilk that could grow moss. The sigil referenced the dimensionality of sound in the project. Cumulatively, the measures contribute to a synesthetic,[2] continental-scale score in progress for the Overture and First Movement. The Overture was installed on the summer solstice of 2015 in Peekskill, New York, and the elements were immediately submitted for copyright registration. Rather than copyrighting the forests endangered by natural gas pipelines in The Blued Trees Symphony, we copyrighted relationships between the human teams, the art, and the trees in their habitat. (In writings and interviews, I have been careful to describe the work as being with the trees rather than on them.) We received confirmation of our registration that fall (figure 1).

In this article, I present the Blued Trees project as a case study in eco-art, defined here as art integrated with ecological habitat and intended to avert ecocide.[3] As the international legal discourse surrounding ecocide evolved in the 1970s, interest from artists engaged with environmental issues also accelerated, contributing to the rise of eco-art.[4] The concept of “ecocide” has gained legal traction since 1970, when bioethicist Arthur Galston first pronounced an ecological equivalence with genocide.[5] However, ecocide has been erratically prosecuted. The term “ecosuicide” was popularized through the controversial writings of Jared Diamond (2005), who proposed that the collapse of Easter Island’s civilization was self-inflicted ecocide. (Some evidence indicates that it was actually caused by European genocide from slave trading and diseases introduced by traders; see Peisner 2005).

I chose a transdisciplinary approach because I agree with physicist Nicolescu (2002, 2014), who argues that transdisciplinarity is uniquely the in-between path out of complex ecological disasters that manifest in cascading relationship to each other. He has variously referred to that knowledge space as “the space between” or “the hidden third,” writing in 2017, “What is that in between the boundaries, which crosses the boundaries, and is beyond any boundaries? That I called transdisciplinarity” (Nicolescu and Versluis 2017). Blued Trees draws on artistic performance, music theater, musicology, ecological science, complex systems theory, legal theory, and activism (Rahmani 2019), making them elements in a tool kit to heal ecocide with art. These relationships comprise a complex adaptive model (CAM), a way to apply algorithms to predict outcomes between agents. A CAM applies algorithmic rules to analyze relationships between dissimilar agents and predict outcomes of interactions. In my case, rather than numbers and formulae, I am looking at relationships intuitively from the point of view of an artist considering formal relationships. The Blued Trees Symphony experiments with the “in-between” space of rules from a range of disciplines, including law, music, art, and science in both content and form.

This project applied “trigger point theory,” my original approach to ecological restoration, premised on the principle that small points for intervention can affect the biogeographic health of large landscapes, in ways akin to what others have called the “butterfly effect” (Hilborn 2004; Rahmani 2012). Trigger point theory presumes that art can contribute to the “common good,” realizing impacts of small emergent changes in complex systems.

In 2015 the Algonquin Incremental Market (AIM) expansion project owned by the Spectra Energy Corporation proposed a path that passed within feet of an aging nuclear facility in Peekskill, at Indian Point, approximately thirty miles from New York City, on the east bank of the Hudson River, which empties into the Atlantic Ocean in New York Bay. The location is biogeographically sensitive and potentially disastrous for installing a (larger) pipeline carrying high-pressure, volatile fracked gas. I identified the site as a “trigger point.” In what follows, I present the basic “rules” of trigger point theory, then outline my application of them within the legal strategy for the intervention made by the Blued Trees project, present the musical ideas informing the work (which parallel the legal intervention), and describe what ensued in the work’s performance.

Trigger Point Theory: Applying Rules to Make Change

Trigger point theory was developed in a ten-year-long work entitled Ghost Nets (1990–2000), as I began to engage strategies for “collaborating with the environment” inspired by my study of Native American practices (figure 2).[6] I bought a former coastal town dump and lived there full-time for ten years while “bioengineering” the site to turn it back into flourishing wetlands. Worldwide, the loss of wetlands has contributed to fisheries decline. I planted four hundred trees on the site, gleaning insights from my observations to apply to conserving or fostering contiguity in projects elsewhere. Those ten years of work were divided into three-year conceptual increments, with musical allusions to the passage of time, to sequentially restore the watershed, uplands riparian zone, and wetlands. Ghost Nets became an exercise in applying transdisciplinary metaphors to ecosystem restoration. The project was research in effecting a trigger point in the Gulf of Maine.

In 1996, as I was preparing to excavate and restore the buried estuary at the Ghost Nets site, sculptor Peter von Tiesenhausen was copyrighting the top six inches of his entire ranch as an artwork, to stop natural gas corporations in Alberta, Canada, from taking his land. Although the case was never adjudicated, he successfully discouraged the oil corporations from seizing his land. Nearly twenty years later, his example inspired FrackBusters NY, New York State activists who, in their search for an artist, connected with me to build on his example. When they showed me the New York state maps indicating where natural gas pipelines were proposed in forest corridors, I recognized an opportunity to develop a continental-scale installation in the proposed corridors and make it the subject of case law (figure 3).

My immediate precedent for working with biogeographic features and ultramarine blue paint was Blue Rocks (2000–2005). In a composite drawing on tracing paper, modeled after the “father” of modern landscape architecture Ian McHarg’s (1969) rethinking of urban planning, I layered tracings of geographic information system (GIS) mapping of a too-narrow culvert in a drawing to discover where patterns of habitat edges and water systems would provide support for biodiversity. If tidal flushing were restored by expanding the culvert, it would restore contiguity for twenty-seven acres of degraded wetlands and transform them into a regional trigger point (figure 4).

Both Ghost Nets and Blue Rocks applied trigger point theory to principles of island biogeography in edge habitats. In Blue Rocks, I drew attention to the causeway problem by painting forty large boulders along a public road with the same nontoxic ultramarine blue casein blended with mosses that was later used in The Blued Trees Symphony.[7] In The Blued Trees Symphony, I built on Ghost Nets and Blue Rocks, analyzing relationships between small sites and large systems in crisis, by applying six rules of a trigger point theory CAM to environmental justice with an eye toward policy change. As in earlier works, ideas about musical forms were used to shape emotive experiences of change over time. Painting the original Overture and additional measures across the continent[8] was intended to define transitions between physiological differences experienced by an audience from an agitated tempo to a slow tempo (lento), common in any symphonic composition and recapitulating the experience of asserting environmental justice over ecocide. The Blued Trees Symphony is thus located simultaneously at continental and local scales, in pragmatic legal discourse and the emergent imaginary (figure 5).

The Blued Trees Symphony follows the six rules of trigger point theory. My premise was that these rules could identify emergent change, be strategically leveraged, and be amplified with eco-art to effect common good. The rules developed theories of change from quantum mechanics for application to CAMs, as in climate change modeling.

-

Stay in a paradox of time. Despite urgency, there is time for change. String theory physics tells us that time is flexible and multivariant (Guillemant and Medale 2019). In music, the organization of tempos manipulates emotive perceptions from a range of elements in time. Law is also a continually evolving process of parsing justice over time. In The Blued Trees Symphony, urgency culminated when Spectra Corporation destroyed the Overture (described below). Developing a long-term strategy positioned the project to affect public opinion over time. Musically, I could redefine the way forward over spans of years in staggered relationships. An example of this was in the continual expansion of measures of the First Movement. The Coda was conceived as a brief event for the weeks before the 2016 US presidential election.

-

Play will teach. Precursors of this idea can be found in John Dewey’s ([1936] 1980) writings on art and education, in science fiction, and in contemporary game theory. Even at the brink of disaster, thought experiments can rearrange players and agents to find new options—for example, by analytically applying Boolean theory (Boole [1854] 2003). Organizing the performative aspects of the work seemed to playfully invigorate communities’ commitments to save their forests, creating experiences that were both joyous and contemplative (figure 6). The mock trial (described below) was “serious” play on the themes of ownership and safety.

-

There will be a small point of entry for intervention in large chaotic systems. In chaos, self-organization can occur at multiple points. My judgment had been that the legal overlap between copyright, eminent domain, and “Earth rights” to protect the ecological art was just such a small point of entry, a possible point of cultural emergence establishing a new paradigm in a chaotic judicial system. Successful legal intervention depended on leveraging this overlap for Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) protection of art in collaboration with trees, permanently fixed in the habitat ecosystem of the land on which it is composed.

-

There will be critical, unexpected, opportunistic disruptions in sensitive initial conditions. The challenge is to notice the small anomalies in an otherwise predictable system, as agents of emergent change leading to self-organization. Von Tiesenhausen’s bold assertion of copyright power was an example of disruption. The eventual destruction of our work and tragic loss of forested habitat in Peekskill was another disruption that inspired the project’s continental-scale expansion.

-

Metaphors can be idea models. Trees are living metaphors for systemic interdependence. A classical symphony presents metaphors in a complex discourse between musical elements and instruments over time. In habitats, contiguity is a metaphor that negotiates comparable levels of complexity to achieve a harmonious balance that permits resilience over time and space. In law, it is through the accumulation of many complex and often disruptive discourses rendered in individual instances of case law that justice can be won. In each example, time is determinative with metaphorical qualities.

-

Layering information will test our perception. Layering data can facilitate conclusive connections. Ecological disasters interact and cause cascades of secondary effects. Habitat fragmentation is not only a threat to watersheds and a source of loss of biodiversity but also a cause of new viral infections across species (zoonosis), contributing to imbalances that threaten human life. The Blued Trees Symphony was informed by GPS mapping, discussions with legal experts and local communities, and identification of the critical biological importance of individual trees and forest contiguity. The difference in The Blued Trees Symphony from my earlier work was that my layering went beyond assembling statistical data and ecological systems to include layering other disciplinary points of view, specifically from music and from law.

Ecocide, Eco-art, and the Law

The legal means for preventing ecocide have been developing for decades. In 2010 UK-based environmental lawyer Polly Higgins moved the legal discourse about ecocide forward by proposing an amendment to the Rome Statute at the United Nations, which had already established the link between ecocide and genocide in the International Criminal Court. The amendment was argued in a mock trial in the UK Supreme Court, helping to pave the way for a children’s lawsuit initiated by Earthjustice (joined by Greta Thunberg) against the United States. The children’s lawsuit proceeded to the United Nations under a section of international law on “the rights of the child.” The grounds for the suit are that support for fossil fuels endangers children’s futures (Johnson 2019). Higgins’s goal before she passed away in 2019 had also been to litigate in The Hague before the United Nations on behalf of Earth rights. Prosecutable laws naming ecocide as a criminal offense have since been adopted by ten countries, but none have yet established standards to assess intentionality or provide enforcement. These legal trajectories implicate fossil fuel corporations in genocide against an entire generation by ecocide.

Higgins fought for case law on ecocide and nonhuman rights (Higgins 2010; Higgins, Short, and South 2013) in the UK Supreme Court. She demonstrated, in a mock trial, such as the one that would later be initiated for The Blued Trees Symphony in 2018, possibilities for future litigation. Since Higgins’s mock trial, intransigent extractive corporations and those clamoring for environmental rights have increasingly clashed. As the broader culture considers ecocide, which may now include the impacts of pandemics like that of COVID-19,[9] it becomes more likely that one of these suits will prevail.

Consequences of fossil fuel use disproportionately affect young people as well as communities of color, and particularly Indigenous communities internationally. The moral implications of that injustice have been frequently observed (e.g., Healy and Barry 2017). From the late 1990s onward, activist lawyers began filing amicus briefs against major corporations such as Shell, Chevron, Chiquita, and the World Bank, implicitly demanding a confrontation about how eminent domain laws fail to protect “Earth rights” from ecocide. More recently, environmental justice concerns made it into broad public discussion in the context of events surrounding the Standing Rock Sioux Water Protectors’ actions to protect their watershed from natural gas pipelines. The North Dakota Water Protectors gained significant international attention before Donald Trump’s election to the presidency.[10] Trump was an investor in the Spectra Energy Corporation, which ignored due process, both at Standing Rock and at the site of the Blued Trees Symphony Overture, to install pipelines on the land. As of this writing (July 2020), legal challenges prevailed in North Dakota to shut down the pipelines. Simultaneously in Virginia, pipeline plans were abandoned by Dominion and Duke Energy. Artist-curator Robin Scully helped trigger cascades of multiple regional legal initiatives as an early responder to the threat of natural gas pipelines. She organized volunteers to paint hundreds of trees for the project in the corridor where Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) continues to be resisted.

Cuban activist artist Tania Bruguera refers to her and other artists’ engagement in policy matters to effect change as “artivism.” Artivists are inspired by the work of activist artists, such as Joseph Beuys, who founded the Green Party and the genre of “social sculpture” to engage communities with governmental policies in search of justice (Rojas 2010). In 2016, inspired by the devastating Deepwater Horizon 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the UK-based organizations Liberate Tate, Platform, and Art Not Oil began campaigns for Tate Modern to divest from BP, culminating in 2017 with public dialogue over divestment from fossil fuels. Staged events and photo ops of media-friendly images, such as pouring oil over a naked body in the Turbine Hall, successfully enlisted mainstream sentiment and accomplished divestment.

The international advance of arguments against fossil fuels and the “rights of nature” has been framed as a culturally significant conceptual shift (Knaus 2018). That shift relates to the broader policy question of who or what has rights. A series of recent habeas corpus amicus briefs to protect chimpanzees failed to prevail in courts but did raise salient questions (Staker 2017). Geomorphic features are being granted legal protection, as with the Whanganui River in New Zealand and the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers in India (O’Donnell and Talbot-Jones 2018). Case law from these decisions may indicate a wider shift in global judicial consciousness. The relevance to The Blued Trees Symphony is the recognition of the values of common good that challenge narrow definitions of commodified ownership and corporately defined public good.

The Blued Trees Symphony: Copyright as Challenge

With the goal of preventing one form of ecosuicidal industrial development—pipelines bringing fossil fuels across the North American continent at a time when a growing number of climate scientists have urged us to “leave it in the ground” and preserve forest contiguity—I decided to combine art and law to present an alternative to pipeline construction and inspire planning based in Earth rights. By November 2015, despite a cease-and-desist letter sent to Spectra Energy Corporation, construction of this particular pipeline proceeded, leading to the effective destruction of The Blued Trees Symphony’s Overture. Rather than stymying the project, that destruction inspired me to add measures of the First Movement across the North American continent (Rahmani 2018).

I registered The Blued Trees Symphony for copyright to challenge the limits of the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA). VARA protects the rights of permanent art of recognized art historical stature but not site-specific (movable), transient, or activist art. I maintain that Blued Trees is not a transient work. It is as permanent and integral to the site as the life span of each tree-note and the rock formations the casein touches between the roots (figure 7). I intended to seek VARA’s protection for eco-art as a new genre. In international events presenting the project, I could advance discourse about eco-art as a distinct genre with audiences in South Korea, China, the United Kingdom, France, and Japan and at multiple venues in the United States to fulfill attorney Patrick Reilly’s mandate to win in the court of public opinion.

The legal theory behind my challenge built on originalist linguistic interpretations of copyright and eminent domain law, which references the spiritual aspect of art and the inviolability of the family home. The implications of protecting forest trees with art questions current definitions of common versus public good and ecological values that might determine ownership. My focus on the aesthetic complexities also separated this work from activist art. Meanwhile, the stature of the project continues to rise as it evolves internationally as a symphony, an opera in progress, a series of gallery installations (figure 8), interviews, and writings including publications in law journals (Jaya 2017).

The language defining legal theories of copyright (or droit moral, sometimes called a “spirit of art”), eminent domain ownership (the “sacred home”), and common good originated in the Age of Enlightenment. This language reflects broad and persistent social values first articulated in the Napoleonic Code (Landes and Posner 2009; Lobingier 1918). Historically, the Enlightenment was a time when trust in reason and science began displacing reliance on monarchies and religion. In The Death of Nature ([1980] 2006), historian of science Carolyn Merchant blamed the Enlightenment for contemporary Western society’s disassociation from nature and the reinforcement of patriarchy (Merchant [1980] 2006). For decades, an argument against copyright law, which accelerated in the digital age, has been its association with capitalist property ownership. However, that view ignores the power of the phrase droit moral and its implications in eco-art for a harmonious spiritual relationship between artist, art-making, and land. I speculated that in court, these ideas might gain traction with conservative judges invested in legal originalism, the idea that the historical intention of specific legal text is inviolate.

The spiritual implications of copyright law language parallel references to the home’s “sacred” inviolability in eminent domain law. Arguably, both conflict with narrow current utilitarian interpretations of property rights, which now privilege the economic interests of private corporations above common good (Fromer 2014). In contrast, the original language, reinforced by eighteenth-century commentary (Montesquieu 1977), implies a relationship between common good and public good. Those implications overlap the thinking of ecological economists (Costanza et al. 2014; Daly and Cobb 1994; Daly 1996) but diverge from recent court rulings.

The strategic goal of The Blued Trees Symphony was to “culture jam” legal tropes (Delaure and Fink 2017) in order to question inconsistencies in certain assumptions. Although the project is not inherently activist, the strategy pursued with my legal team is classic legal activism, aiming to overturn traditional models and assumptions (about capitalist socioeconomic goals, corporate entitlement, and the like) by awareness rather than through win-lose outcomes. I employed this strategy to dare conservatives to pay closer attention to the “originalism” that they tout—that is, by questioning their interpretation of the language. When the copyright registration was confirmed, it positioned the project to contest eminent domain takings of private property and preserve forest contiguity. Since the artwork was on private land, protecting it (since it couldn’t be moved) contested corporate entitlement. However, protection required an injunction. To our dismay, we did not have time or money to advance into court before the site was destroyed.

We failed to advance the case in an actual courtroom, but following Higgins’s precedent, I partnered with A Blade of Grass (ABOG) to produce a mock trial. The mock trial for The Blued Trees Symphony took place on June 18, 2018, slightly more than three years after the project launch, at the Cardozo School of Law in New York City (figure 9). It was largely choreographed by copyright lawyer Gale P. Elston, who represented me with Steven Honigsman. The Blued Trees Symphony was the plaintiff arguing against the defendant, a hypothetical natural gas corporation. Elston wrote and coordinated scripted briefs. She obtained lawyers who participated pro bono and worked with Jan Cohen-Cruz of ABOG, who enlisted actors for some roles. Elston’s office structured the trial, prepared arguments and briefs, and recruited April Newbauer, Supreme Court judge for the Bronx. The result was a judgment from Newbauer for a temporary cease-and-desist injunction to stop work on the pipeline.

As with Higgins’s mock trial, real lawyers argued the legal theory based on the testimony of witnesses, with real evidence, a real jury decision, and a judgment rendered by a real judge. The main difference between Higgins’s theory of ecocide and the theory advanced to protect The Blued Trees Symphony was the introduction of eco-art into the arguments. The trial encompassed arguments from corporation representatives, the landowner, art experts, me, and comments from the jury. When Newbauer adjudicated the temporary injunction, she advised counsel to seek resolution.

Newbauer said she reached her decision on the basis of standing, which validated Reilly’s advice. Newbauer explicitly stated that testimony from art critic Ben Davis, who affirmed the significance and legal standing of the work in a wider art world discourse, was the deciding factor. Davis positioned the artwork in the vanguard of discourse about the role of law and nature in contemporary art. Newbauer’s injunction had an effect similar to philosopher of science Karl Popper’s (1963) assertion that scientific theorems need to be falsifiable: if a counterargument might be imagined but there is a preponderance of evidence that implies it could be true, that evidence can be the basis to accept the theory. The injunction left the door open for further adjudication in comparable cases. The goal of the subsequent mock trial had been to press for an expanded legal definition of sculpture in court that would include eco-art and that I identified as sonified biogeographic sculpture. That potential remains.

Despite the gravitas of the mock trial, there were moments of levity and whimsy. I had the artist-curator Robin Scully bring the cut remains of a painted tree into the courtroom from the Virginia site of a tree massacre, and a “tree translator” interpreted the song of the trees. Blued Trees music was piped into the courtroom and translated as testimony by Toya Lillard (figure 10).

Fictional legal dramas often imply one-to-one relationships between legal theory and justice. But the legal system grinds slowly. The world created by the judicial process depends upon numerous litigatory experiences. In the case of prosecuting ecocide or protecting The Blued Trees Symphony, case law might build to a conclusion that may take many more decades to effect than our species may have to avert ecosuicide (figure 11). But there are still many legal options to explore.

The Blued Trees Symphony: Sonata Form in Five Movements

After beginning The Blued Trees Symphony, I studied music theory for two semesters at the Juilliard School to refine my thinking (2018) about rules of harmony, counterpoint, and dissonance. They became my semiotic models to ground a symbolic discourse unfolding in time. The acoustic ecology (captured on-site sound) aspects of The Blued Trees Symphony were integrated into subsequent phases of the project and were added to gallery installations that were offshoots of the original project. If history might be considered as the organization of time in human terms, I considered The Blued Trees Symphony an organization of time in musical terms. Time, or the progress of change, is represented differently in law, art (including music), and science, but their core logic is arguably vested in similar values about conflict and its resolution: science is bounded by rules of logic; justice can be reconciled through case law; and music theory aims to resolve harmonic complexity and tension. During the Enlightenment era, music theory advanced harmonic goals in rules for sonata and symphonic forms. The classical European sonata form explores tension and resolution in harmony and disharmony between musical themes (Rosen 1998).

Blued Trees developed two lines of legal arguments expressed as musical themes presented and developed over time. The themes of “common good” and “environmental justice” pivot on the ecological role of trees in complex systems. The former proposes new case law to protect Earth rights, aligning copyright and eminent domain law. Our submission for copyright protection included the map of the Overture, a photograph of tree-notes, and the original melodic score (see figure 1). This is an expansive conception of musical composition, which includes other species—in this case, trees—as performers, acoustic collaborators in an ecologically inclusive world. When tree-notes in each scored measure of The Blued Trees Symphony are painted, they resolve the tonic foundations of the musical refrain. In each measure, local geographic elements such as topography determine additional chords and embellishments, which are then transposed into the written score. The conceptual tension of my counterpoint in The Blued Trees Symphony circles the dissonance of anthropocentrism and ecocide as opposed to the lyric complexity of idealized harmonic interspecies interdependence (figure 12).

Neuroscience evidences that absorbing a new idea, like hearing new music, is an emotional experience requiring duration (Trost et al. 2015). Sound of any kind is delivered to the human ear in envelopes whose shape is determined by physics. In a symphony, we hear harmonic ideas unfold in sufficient time, with enough variation in how the information is framed—for example, changing signature keys or tempos—to allow understanding. The sonata form expresses a yearning for the reconciliation of experiential extremes expressed musically and formally organized as exposition, development, and recapitulation. The five movements of The Blued Trees Symphony each evolved to articulate different relationships with time and trees, expressing the yearning of iterated refrains as steps and variations through moods to identify and resolve dissonance (figure 13).[11]

The first movement of a classical symphony is an exposition of the whole work often presented in sonata form, beginning briskly, entering a largo (slow) phase, continuing with vigor in subsequent movements, and closing with a vibrant flourish. The ongoing First Movement of this symphony with trees began briskly with joyful optimism about beauty and justice.[12] The composition proceeds with slow determination to bear witness to ecocide, even as performers felt the forests consoled us. At every stage, participants and I engaged with conventional and social media, widening a public discourse by sharing our experiences. On the ground, participants identified “sentinel” trees (individual trees whose presence in the larger forest system might be remarkable for a variety of reasons) as tree-note candidates and then walked the terrain, counting steps between tree-notes to iterate the spatial pattern that corresponds to the aerial melodic refrain.

Painting the individual tree-notes in a measure requires intimate, synesthetic relationships with each tree and its surfaces. Painters often must physically embrace each tree to complete the painting as a three-dimensional sigil around the trunk of the tree, rather than simply marking two-dimensional signage; this literally makes participants “tree huggers.” Documenting the tree-notes using GPS and photography recorded hundreds of individually performed, crowdsourced, hand-painted, kinetic, and sonified biogeographic sculptures (figure 14).

The First Movement expanded measures at sites in New York State, Virginia, West Virginia, and Saskatoon, Canada. At each location, one person usually took the responsibility of organizing a team. In Virginia, on Brush Mountain outside Blacksburg, artist Robin Scully personally supervised the painting of more than two hundred trees. At the time of this writing, a new measure is imminently projected for installation at a site near Lake Superior, which will be integrated into the whole composition.

The Second Movement was completed in the fall of 2015.[13] Activities were performed at an agitated tempo (agitato) during a two-month residency supported by the National Endowment for the Arts at the International Studio and Curatorial Program in Brooklyn, New York, near the Newtown Creek Superfund site. There were no healthy trees at the site, so none could be painted. The transposed thematic discourse was between data points rendered in a series of encaustic drawings and local sound. An audio mix for the Second Movement became part of a performance making comparisons between the fossil fuel contamination at Newtown Creek and the pattern of natural gas pipeline infrastructure spreading across North America. The performance was accompanied by projections of mapping onto the encaustic drawings that compared the proposed future natural gas infrastructure plans for New York State to conditions at Newtown Creek. I conjectured that the entire state, and possibly the entire continent, could become a toxic site if natural gas companies went forward unimpeded.

The in-progress Third Movement continues to track the legal theory of the project. I see this movement as a representation of heroic lawyers systematically challenging ruthless corporations. A work-in-progress libretto includes text from case law and the climax of the mock trial that may become an opera. The tempo has been very slow (largo). The Coda layered recordings of vocalization based on the iterated measure and the narration of legal conclusions from other cases with an acoustic veil from the interior sounds of trees composed by Maile Colbert.[14] Classically, coda tempos are fast (presto). In this composition, the Coda was deliberately composed fast under the urgent pressure of and framed by the 2016 US election, but the actual tempo of the completed work is deliberative and largo. If the coda of a symphony must represent a dramatic finale that recapitulates what came before, arguably the election results were a dirge for elusive justice at that moment in history.

Reading music is a transdisciplinary and synesthetic event. As a musician reads the visual representation of notes, they must imagine hearing sound to express the notation embodied in instrumentation. In a conventional symphony, a seated audience has an acoustic experience in a defined window of time. The goal is to maximize an emotional experience that builds to a crescendo and resolves to harmonic catharsis in the denouement. However, time and tempo in the unfinished movements of The Blued Trees Symphony continue to develop, shaped by the realities of environmental hope and crushing disaster (figure 15). The implications of the synesthetic formalism of Blued Trees and The Blued Trees Symphony are relevant to environmental justice (figure 16).

Outcomes and Conclusions

Historically, art often serves as “cultural glue” that helps humans survive a range of challenges. I assert that humans have never needed adaptive glue more desperately than we do now to survive ecocide. My fundamental premise in The Blued Trees Symphony has been that as art is cultural glue that allows community adaptation to crisis, trees are anchors of the forest contiguity that protects humanity. There are legal remedies to protect those anchors spiritually as well as practically. The Blued Trees Symphony presents a legal theory based in droit moral that aspires to glue together human communities and landscapes threatened by ecocidal policies to the tree “anchors” that sustain our sacred home.

The Blued Trees Symphony had three goals:

-

To perform with trees across miles of forest

-

To legally advance a new genre of art to establish a wider legal discourse

-

To create an alternative narrative to ecosuicide

Each of these goals was accomplished to some degree. The first by far exceeded my original ambitions.

In recent years, corporations have run roughshod over due process to narrowly decide for public good against common good. In March 2018, in Virginia and West Virginia, the hundreds of painted trees in the First Movement remained untouched. The next month, just before performing the mock trial, gas companies ignored the rights of property owners to due process as well as warnings from scientists. They began indiscriminately cutting down trees on private land, despite ongoing protests and court cases, to make way for their pipelines. Cutting the trees occurred with the support of local officials, but shortly after beginning excavation for the pipeline, companies were forced to suspend work because severe erosion threatened local communities. The erosion was caused by the clear-cutting to install the pipelines. In comments to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, a board of corporate appointees that oversees natural gas pipelines, the erosion had been predicted (figure 17).

As with the Platform and Standing Rock events, the approach I pursued in this project depended on leveraging broad interest through social media. It was not a project intended to accomplish standing and attention in a museum venue, but it has generated some seventy interviews, essays, participation on panels and in book chapters, videos, and installations since 2015, in addition to social media conversation.

Legally, I had multiple initial motives for a test case. Besides establishing eco-art as a distinct genre with copyright protection, “culture jamming” eminent domain law, and protecting the waters and contiguous forests that humans depend upon to survive climate crises, the overarching goal of winning the case in the court of public opinion was to enlist new resistance to ecocide. The “spirit of art” terminology implies a special, reverent relationship to art as a key aspect of human culture. That assertion of cultural rights agrees with findings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that cultural aspirations, as argued by litigators against ecocide, often entwine with spiritual values, and that culture must be given equal consideration as economic well-being while the human community attempts to adapt to climate change (figure 18).

The Blued Trees Symphony did not stop natural gas corporations in Peekskill, Saskatoon, or Virginia. When Spectra could not be prevented from destroying the Overture, the next priority became identifying pro bono lawyers at each new site to litigate a test case in local courts. Although I had hoped to see a test case litigated in court to create new case law and effect an actual injunction, the mock trial injunction still set important precedents for the legal theory. The legal theory of the project evolved and continues to evolve in conversations with several lawyers, including copyright lawyers Patrick Reilly, Gale Elston, and Jonathan Reichman, individuals at Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts (in New York), and environmental lawyer Marcia Cleveland, and in discussions after my appearances on panels at various universities.

This project has provoked public conversation around where the spirit of art resides (as protected by copyright law), whether common good might be aligned with public good, and what public good means (challenging values currently enshrined in conservative eminent domain real estate law). Ecocide may have been the dominant voice echoed in the movements of The Blued Trees Symphony, but the secondary theme of artivism, expressed in international legal activism to counteract ecocide, cultural resilience, and the songs of the trees themselves, still rings out. While science and the judicial system may work more slowly than art or music to produce affective results, and while The Blued Trees Symphony has not yet established formal case law, it still represents aspirational environmental justice.

I have presented The Blued Trees Symphony as a case study in new strategies to attain resilient environmental policies. I described the context from which trigger point theory emerged as a CAM and the rules for applying the theory. I suggest replacing arbitrary judicial boundaries and policy rules with a Blued Trees CAM that we might use to resolve our vulnerability and interdependence with other life, including trees. If we proceed from a transdisciplinary, synesthetic vantage point, we may be better equipped to counteract ecosuicide.

Trees inhabit a web of life torn apart by greed. In corridors of complex forest systems slated for sacrifice, sentinel trees still sing arias. In measures that remain intact, tree songs can be heard. They echo in the memories of people who knew the tree martyrs. A Blued Trees policy would leverage a small but disruptive idea, a trigger point, in copyright law by asking where the spirit of art might meet in our common, sacred home of the Earth. Another set of court events may one day hold ecocidal “war criminals” accountable for their devastations. Meanwhile, The Blued Trees Symphony offers a model to help leverage environmental policy change in perilous times.

These words are from Patrick Reilly, lawyer and copyright advisor, in a 2018 email correspondence with the author.

Synesthesia is a neurological condition that conflates visual and auditory perception. This project appropriates that terminology.

“Ecocide” is defined here as humans deliberately destroying the natural world, leading to the collapse of nonhuman ecosystems and the subsequent collapse of human civilizations.

Artists who emerged to catalyze a wider discourse included Alan Sonfist, who first proposed Time Landscapes in 1965 and who began internationally installing minigardens of Indigenous plantings; Newton and Helen Harrison, who combined poetic text with ambitious continental illustrations of future alternative possibilities in major installations; Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who framed the significant labor of those who sustain the world, from housewives to maintenance workers, in 1969; and Mel Chin, who created Revival Field in 1991, to illustrate plant remediation of toxic soil.

As part of the Sub-commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Human Rights think tank for the United Nations, in text prepared by Special Rapporteur Benjamin Whittaker, in 1982, one section referenced that some participants advocated conflating ecocide with genocide and ethnocide as “threats to entire populations.” Subsequently the question of “intentionality” was debated in the United Nations.

Ghost nets are the invisible monofilament fishing nets that drift away from boats and strip-mine the sea of life. I appropriated the term to describe how familiar human ideas and routines effect ecocide.

Despite being given formal permission from the town manager to paint the rocks as public art, I was issued a subpoena to “wash the rocks.” A public “wash-in” was prefaced by locally published announcements, was visible to passersby, and drew additional attention to the site.

Increasingly, more than patience is required to effect reasonable environmental policies. Environmental activists internationally are coming under life-threatening corporate and governmental pressure, particularly in Latin American countries like Brazil and Mexico. Dangers to environmental activists have been detailed in an online report by Earth Rights International (2018).

It could be argued that because zoonosis seems to arise from habitat fragmentation, ecocide is the cause and genocide is the effect.

The Standing Rock Water Protectors ultimately took their plaint to the UN Human Rights Council. The corporation subsequently attacked the tribe and bulldozed through its sacred lands to install the pipelines.

Sources have included the Juilliard School, the Geology Department of Lehman College, City University of New York, Harvard Forest, and the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire.

The Ultramarine Choral is an electronic composition by sound designer Maile Colbert (for the 2015 overture in Peekskill, New York) that initiated painting the First Movement and was subsequently used in my short film Blued Trees (2015). See https://soundcloud.com/maile-colbert/ultramarine-choral-for-aviva-rahmanis-blued-trees-project.

The Second Movement of The Blued Trees Symphony transposed heavy metal toxic contamination monitoring data points collected by the EPA in Newtown Creek, Brooklyn, New York, with MuseScore and mixed it with a recording of local traffic sounds captured by artist Dylan Gaultier. See https://soundcloud.com/ghostnets-1/second_movement_blued_trees_symphony.

The Coda’s score has been presented in conferences and exhibitions, as a stand-alone sound installation, and as a live performance requiem. This recording includes vocalists Aviva Rahmani and Debra Vanderlinde. Actor: Dean Temple. Composers: Maile Colbert, Aviva Rahmani. See https://soundcloud.com/ghostnets-1/excerpt-from-the-coda-of-the-blued-trees-symphony.