Introduction

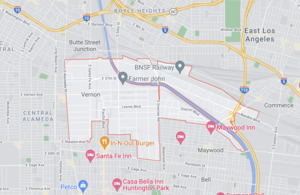

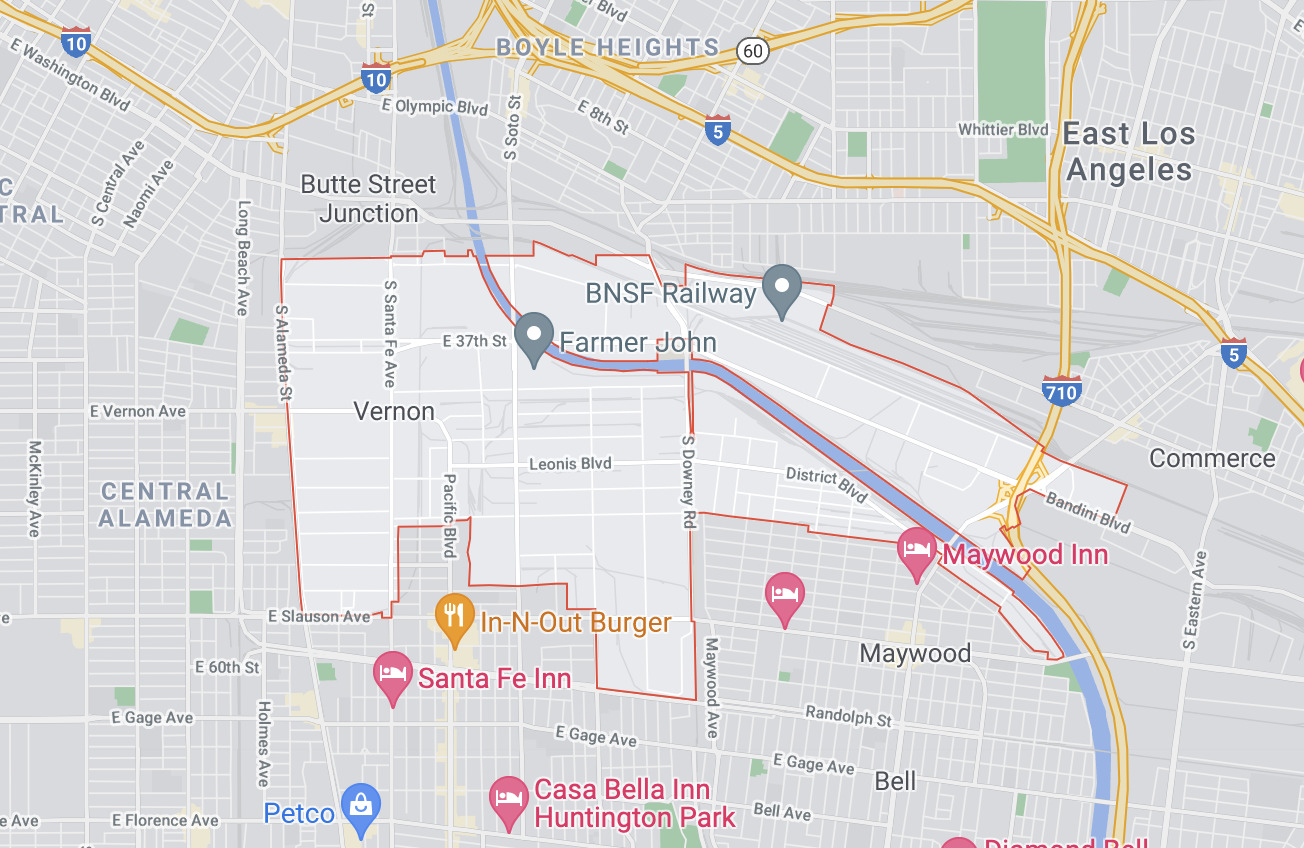

In March 2015, facing potential criminal charges from federal investigators with the Department of Justice (DOJ), Exide Technologies was finally forced to permanently shutter its lead-acid battery recycling plant in Vernon, California, a five-square-mile industrial zone just five miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles (figure 1). For decades, the plant had spewed toxic chemicals into the air and water, exposing thousands of families living in the surrounding neighborhoods to dangerous levels of lead and arsenic.[1] These neighborhoods—Boyle Heights, East Los Angeles, Commerce, Bell, Maywood, and Huntington Park—are predominantly working-class and Latinx; they are also among the most disproportionately burdened by pollution and industrial toxicity in all of California (“Draft CalEnviroScreen 4.0” 2021). The DOJ’s involvement followed years of frustrated opposition to the plant by local community members and organizations who urged various state regulatory agencies to act on Exide. While California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) and the South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD) issued multiple fines and citations against the plant over the years, the agencies had failed to stop Exide from emitting toxins and poisoning surrounding communities.

Unfortunately, the plant’s shuttering was only the start in a protracted process of seeking redress for those poisoned by Exide, and one that has required constant vigilance from the impacted communities in the face of a regulatory apparatus and legal system that strongly favors corporate interests. As mark! Lopez, former executive director for East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice (EYCEJ), put it in 2016, “every step of the way this cleanup has only moved forward through community pressure” (Barboza and Poston 2016). Such was the case in 2018, when California lawmakers were pressured by resident activists to expand the remediation project to include the area’s parkways—narrow strips of public land separating the sidewalk from the street—which had been excluded from the DTSC’s original cleanup plan (Barboza 2018).

The ongoing cleanup of the contamination site and the surrounding residential area is the largest and most expensive in the history of California. The most recent report by state auditors estimates that the final cost of the cleanup will be about $650 million, of which only about $250 million had been authorized at the end of 2020 (“California Department of Toxic Substances Control—The State’s Poor Management of the Exide Cleanup Project Has Left Californians at Continued Risk of Lead Poisoning” 2020). Over 10,000 properties lie within the preliminary investigation area outlined by the DTSC, a 1.7-mile radius around the plant that includes homes, schools, parks, and day care centers. Of those properties, 3,200 were identified as high priority for soil removal and replacement, with soil samples showing lead concentration levels above 300 parts per million (ppm); only 2,557 have been cleaned as of summer 2021. Another 4,600 properties tested with lead levels between 300 ppm and 80 ppm, which California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment has determined is the minimum amount of lead needed to increase blood lead concentration in children to harmful levels (“What Are Acceptable Concentrations of Lead in Soil in California?,” n.d.). There is currently no timeline for cleaning these properties.

Given the terms of the 2015 nonprosecution agreement the DOJ signed with Exide, which eventually allowed it to evade accountability via bankruptcy, it is difficult to see Exide’s admission of guilt as anything more than a symbolic gesture. Yet 2015 marked a turning point in the way Exide’s toxicity was recognized and discussed in broader public discourses, in turn shaping the official response to the crisis, as evidenced by then governor Jerry Brown’s decision to earmark $177 million of California’s General Fund for the cleanup less than a year after the DOJ’s agreement with Exide (Aguilera 2016). In fact, while Exide’s toxification of Vernon and its surrounding neighborhoods is undoubtedly a crisis of material concern, it is also a case that highlights the discursive struggle waged by residents to finally have their concerns acknowledged and addressed by the state. To understand Exide’s impact on local communities, it is not enough to interrogate the material dimensions of Exide’s toxicity; we must also ask how Exide’s ability to spew toxins for so many years reflects a set of ideological assumptions and political judgments held by both corporate and state agents, which subsequently materialized in the form of toxic infrastructure and environmental injustice for Southeast LA residents. Moreover, we might understand residents’ long-standing calls to close the plant and clean the surrounding area as a kind of counterpublic demand, not least in that these calls included marginalized voices excluded from a majoritarian public assumed to be English-speaking. For these voices, what counts as safe, as harmful, as urgent—perhaps most importantly, what counts as justice—has often looked radically different from the official line of Exide representatives and state regulators. Every aspect of the site’s closure and cleanup has been shaped by the conflicting perspectives of the site’s various stakeholders on these very basic discursive questions.

In this article, I examine Exide’s battery recycling plant through a “mediating infrastructures” approach, which I draw from Rahul Mukherjee’s work on cell antenna towers in India and the publics formed in response to the perceived threat posed by their radiation emissions. Mukherjee argues that understanding the health and environmental effects of cell towers requires “examin[ing] the practices and interactions of these different stakeholders, who together comprise the public that gathers around them” (Mukherjee 2016, 99). In the case of cellular infrastructure in India, these stakeholders included cellular operators, antiradiation activists, scientists, and concerned citizens living near cell towers, among others. Together, this cell antenna public participated in the mediation of cellular infrastructure, “where mediation is not mere media coverage but a complex sociomaterial process of understanding the infrastructure in its varied relationships” (Mukherjee 2016, 100). In Mukherjee’s conception, this public includes the media technologies used by experts and citizen scientists to demonstrate the presence of otherwise imperceptible radiation, and its varied relationships include those occurring between the towers and the human body on a molecular level.

To explore the complex arrangement of human and nonhuman agents that come into relation with each other through the cellular tower, Mukherjee identifies three modes of mediating infrastructure: technostruggle, intermediality, and affective resonances, explored in closer detail below. In my analysis of the public formed around Exide, what I term a lead-toxicity public, I draw on these three modes to get at the various levels of interaction between its human and nonhuman agents. This includes Exide officials, state and federal regulators, medical researchers at the University of Southern California (USC), environmental justice organizations, local journalists, and of course the estimated twenty-one thousand families living within the 1.7-mile radius zone around the plant;[2] it also includes the toxic lead that settles into the area’s soil and water, or more disturbingly, into the bloodstream of residents and workers; the X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer used to measure lead concentration in soil; and the nonhuman life affected by the lead-contaminated land and water.[3] I expand on Mukherjee’s approach by more carefully considering the fractured interests and highly asymmetrical power relations that characterize this public, and how that in turn shapes the (re)mediation of this infrastructure. I argue that the local organizations and residents who have fought against the environmental injustice at the Exide plant constitute a counterpublic in the sense theorized by Nancy Fraser, as a “parallel discursive arena where members of subordinated social groups invent and circulate counterdiscourses, which in turn permit them to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs” (Fraser 1990, 67). In Fraser’s theory, counterpublics serve to widen discursive contestation, particularly in the context of social stratification, and in this way harbor the potential for transforming wider public discourse and shaping civic life. In the context of Southeast LA, the counterpublic formed around Exide benefited from a long history of community resistance against toxic infrastructure that dates back to the late 1980s with the Mothers of East LA (MELA), a group that formed to fight against the construction of a new prison in Boyle Heights (Gwash and Schroeder 2014). This lead-toxicity counterpublic’s relative success in recent years is in part a result of intergenerational activism and organizing—mark! Lopez, of EYCEJ, is the grandchild of one of MELA’s founding members, Juana Beatriz Gutierrez (Delgadillo 2018).

The complex dynamic between a majoritarian public sphere and its counterpublics can be seen through the gradual shift in how California regulators have discussed Exide, increasingly adopting the language used by activists to describe Exide’s poisoning of Southeast LA as “systemic racism” (as though the state was not part of the system that enabled this poisoning) (Blumenfeld and Williams 2020). To examine this discursive terrain more closely, my research draws on a range of documentation related to Exide’s toxicity and the site’s (re)mediation. This includes local news coverage of the site; official documents, reports, and presentations by DTSC and other state agencies; and websites, blogs, and social media pages run by community activists and organizations. I focus primarily on the process of environmental remediation that followed Exide’s 2015 nonprosecution agreement with the DOJ, as a way to highlight the interesting conceptual relationship between mediation (in its traditional media studies sense) and environmental remediation, a move inspired by Alenda Chang’s work on EPA Superfund sites. Chang notes that “the proliferation of reports following federal designation of a Superfund site creates a hypermediated sedimentation of documents tracing the site’s diagnosis, course of treatment, and follow-up determinations” (Chang 2015). Although Exide is not a Superfund site, it has undergone a very similar process of hypermediation. The mediating infrastructures approach allows us to read these various documents and mediations for what they can tell us about the site’s publics, and how discursive contestation between various stakeholders comes to shape policy decisions and governance.

Before elaborating on what a mediating infrastructures approach can tell us about the Exide case and its various publics, I begin by briefly outlining the history of the plant and the city of Vernon. Although almost entirely industrial, Vernon is surrounded by densely populated working-class communities of color, which also happen to be composed in large part of immigrant families. These demographics help explain the politics of regulatory laxness in the area, as they limit the political power of the counterpublics formed in opposition to the site’s regulation and management. Here, I also outline the regulatory regime that enabled Exide for so many decades and that is therefore complicit in the ecological disaster at the Vernon site.

In focusing on an instance of environmental injustice created by battery infrastructure, my research is part of a growing body of scholarship that responds to the call by Richard Maxwell and Toby Miller to “green media studies” by developing a materialist ecology of media (Maxwell and Miller 2012). Taking a cue from scholars working in the related field of the energy humanities, my interest in the Exide plant follows from a realization that energy conditions media practice and that battery power has played a critical role in the history of media in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. As such, batteries, in general, are a significant component of the materiality of media, and the plants that manufacture and recycle them, of our media infrastructure. Exide specifically manufactures batteries for use in telecommunication systems and boasts on their website of “delivering energy to critical systems in need of uninterrupted power supply” (“GNB Network Power Solutions,” n.d.).

But even the lead-acid car batteries that Exide processed at its Vernon plant are part of our media infrastructure. In arguing that the automobile should be conceptualized as mobile spatial media, Luis F. Alvarez Leon writes, “cars have gradually enhanced their mobility with capacities to reproduce audiovisual information, and connect into multimedia communication networks that include radio, TV, and Internet broadcasters; car manufacturers; other vehicles; and users of a wide range of devices (such as mobile phones)” (Alvarez Leon 2019, 362-363). While the automobile has been theorized in relation to oil and petromodernity (LeMenager 2016), it is actually the car’s battery that powers these electronic affordances. Aside from the fact that the car itself is a mobile media environment, and an increasingly digital one, the car and the car battery have played an immense role in the development of Los Angeles and its cultural identity, which cannot be extricated from the representations of the city that circulate through media. Los Angeles exists in the popular imaginary as a city where “nobody walks,” or relatedly, where “everyone drives” (Novak 2013). LA’s freeway interchanges, which link the city’s many suburbs, are as iconic as other major cities’ skyscrapers. In this sense, the car battery has been central to the development of the rest of the region’s infrastructure, and to the mediation of its geography (Avila 2006).

I also write about the Exide case because of its wider implications for discourses concerning energy sustainability and environmental justice. There is an irony in the fact that the Exide plant in Vernon was a recycling facility—and one for an industry that promotes itself as the premier global “model for recycling” (“Lead Battery Recycling Model Recognized as Groundbreaking Regulatory Work” 2020). As we continue to approach a turning point in the era of peak oil, the assumed ecofriendliness of electrical power must be more closely interrogated. How can it be that lead-acid battery recycling is simultaneously recognized as both one of the most toxic industries on the planet (“Used Lead Battery Industry Is ‘World’s Worst Polluter.’” 2016) and as “one of the great success stories” of industrial recycling (Ballantyne et al. 2018)? Such an incredible contradiction in the way that lead-acid battery recycling is understood and experienced illustrates a key issue in mainstream sustainability discourse. Often left unexplored in these discussions is what, exactly, is sustained in our efforts to be sustainable. I conclude with a consideration of how the (re)mediation of Exide highlights the limits of mainstream sustainability discourse, and how the work of Exide’s counterpublic points toward more equitable models of sustainability.

Finally, Exide’s poisoning hits very close to home. The house I lived in between 2014 and 2016 is only 3.3 miles from the plant and only 1.6 miles outside the preliminary investigation zone. My high school (where I was a member of the cross-country team and trained across one of the impacted neighborhoods on a daily basis between 2005 and 2009) is just under four miles from the plant. I have friends and family who live or have lived in each of the six impacted residential communities. My concern with thinking more critically about what justice looks like in the Exide case, and who gets to make that determination under what kind of terms, is partially motivated by these biographical details.

“A Personal Fiefdom”: Legacies of Toxicity in Vernon

Although Exide acquired the plant only in 2000, the plant’s poisoning of the local community dates much further back. Under different ownership, the fifteen-acre plant has been a site for metal recovery operations since 1922, and specifically for lead-acid battery recycling starting in the 1970s (“Draft Permit and Draft Environmental Impact Report for Exide Technologies” 2016). Since its emergence in the early twentieth century, lead-acid battery recycling has been “a complex and volatile industry that has experienced dramatic swings in recycling rates with significant environmental and social consequences” (Turner 2015, 30). It has also been an unevenly regulated industry. It wasn’t until 1981 that the state issued then owners Gould Inc. an interim status permit to operate the plant. It operated with this supposedly temporary permit for the remaining nineteen years of Gould’s ownership, and then for another fourteen years after Exide’s acquisition of Gould Technologies in 2000. The DTSC issued the plant more than one hundred safety violations over those years, fifty-nine of them after its acquisition by Exide in 2000 (Barboza 2015b). These violations ranged from improperly storing toxic materials to emitting dangerous levels of lead and other cancer-causing toxins into the air and soil. Even with all these violations, the DTSC’s fines against Exide totaled only $342,000 from 2001 through 2013.

When the Department of Justice became involved in 2013, federal investigators found that Exide committed felony violations by knowingly failing to safely store, dispose, and transport the hazardous waste created by its recycling of car batteries. As part of the nonprosecution agreement the DOJ reached with Exide in 2015, Exide was forced to admit that it had broken the law; in turn, the DOJ agreed not to prosecute Exide or its officers for their admitted crimes (Barboza 2015a). Federal prosecutors rationalized the nonprosecution agreement by arguing that it was the only way to allow Exide to remain a viable company that could be held financially accountable for the damages it inflicted. The reasoning proved extremely flawed—in October 2020, following its second bankruptcy of the decade, Exide was allowed to abandon the site by order of Chief Judge Christopher Sontchi of the US Bankruptcy Court District of Delaware. According to Sontchi, the testimony provided by health experts and environmental regulators over the two-day court hearing, which focused on the public health threat posed by lead contamination, was not enough to demonstrate that there was “an imminent, immediate harm to the general public if this property is abandoned” (Barboza 2020). Exide was allowed to walk away from the environmental disaster without finalizing the site’s cleanup, leaving the massive remediation project to the same agencies that had allowed it to poison Southeast LA in the first place.

That the plant was allowed to run for a thirty-three-year period without a full permit and while consistently failing to abide by the state’s regulations is an indication of the state’s inability (at best), or unwillingness (at worst), to protect working-class communities of color from toxic substances. The state’s regulatory laxness is unsurprising considering the history of Vernon. The city’s motto, “Exclusively Industrial,” reflects not only the concerns and priorities of its local governing body but also the role it has historically played in LA’s greater economy. Founded in 1905, the city of Vernon has effectively been run by the same family for most of its existence. Leonis Malburg, the grandson of one of the city’s cofounders, served as the mayor for thirty-five years, until he and his wife, Dominica Malburg, were convicted of voter fraud and conspiracy in 2009. Until recently, the only residents within the city limits were city employees and their relatives living in subsidized housing. In 2010, during a push to revoke Vernon’s cityhood and dissolve its government, California State Assembly speaker John Pérez described Vernon’s city government as “a situation where a handful of individuals are able to use an entire city as their own personal fiefdom” (Allen 2010). In many ways, Vernon represents a dream city for corporatists—a city run for and by industry interests, with hardly any constituents to answer to. The city’s official website touts the 1,800 businesses and 50,000 jobs within its narrow city limits as evidence of its important role in the region, as the “industrial heart of Southern California” (“Vernon Means Business,” n.d.). It has even been awarded over the years for being the “Most Business Friendly City in L.A. County” (Markle 2014). Yet, while Vernon’s leaders figure the tiny industrial city as a center for growth and productivity, for neighboring residents, the city represents toxicity that stunts growth and terminates life.

Vernon is surrounded by residential neighborhoods whose populations are predominantly low-income Latinx families, many of them undocumented immigrants. The Exide plant sits in the northeastern part of Vernon’s narrow city boundaries. Immediately to the north is Boyle Heights; to the northeast is East LA; to the east is the city of Commerce. Directly south of the plant are the cities of Bell and Maywood, and to the west of them is the city of Huntington Park. The zone encompasses a complicated political geography—counting Vernon, there are five small cities, one unincorporated neighborhood under Los Angeles County jurisdiction (East LA), and one neighborhood within LA city limits impacted by Exide’s emissions. The high rates of lead exposure across these jurisdictions invite us to think critically about the geography of the space; toxicity does not recognize political borders, though political borders often play a significant role in the regulation, the management, and the toxification of spaces.

In the case of Exide, this complex political geography is matched by a labyrinthine regulatory apparatus that has mostly functioned to distribute responsibility and delay real accountability. Although the DTSC is the main agency tasked with regulating the handling of hazardous waste, there are at least five public agencies that held regulatory authority over or involving Exide and that therefore bear some responsibility in the environmental racism that transpired there. For example, in 2008, following complaints filed by residents about dust and ash fallout from the plant, the SCAQMD found that lead concentration in air samples taken near Exide were 66 percent above federal air quality standards. The agency’s solution was to require that Exide process fewer lead-acid batteries at the plant. However, there was no subsequent testing for lead exposure to residents and workers, the domain of the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA). Moreover, these agencies have been reluctant to coordinate their efforts or share their data with each other or with the public. In one particularly frustrating example, the Occupational Lead Poisoning Prevention Program and the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, both operating within the CDPH, maintained separate databases for elevated blood lead levels in workers and children, respectively, but did not compare the databases to better track “take-home” lead exposure brought from work sites into residents’ homes. As USC medical researchers Dr. Jill Johnston and Andrea Hricko argue, “the Exide disaster highlights the silos in which public agencies operate and the adverse impacts these silos have on community health” (Johnston and Hricko 2017, 167). Such siloing makes systematic lead exposure prevention impossible, allowing only for individualized treatment after exposure has occurred, which clearly works to the benefit of industrial polluters.

Local activists fighting Exide and demanding recompense from state regulators have reached the same conclusion, with some demanding that there be a criminal investigation of DTSC and the specific individuals responsible for sanctioning the poisoning of Southeast LA for the benefit of industrial polluters. As the counterpublic formed around Exide demonstrates, when the state cannot be trusted to protect the people against the interests of capital, the community must organize itself for its own protection. If Exide’s poisoning of these neighborhoods is an example of state-sanctioned violence, how might we understand the site’s (re)mediation (which is overseen by the same regulatory apparatus), as well as the community’s response to that remediation? And what role does the community play in protecting itself from future harm?

(Re)mediating the Exide Plant

As Laura Pulido has argued, the environmental injustice of the Exide case is characterized by a regulatory apparatus that, in the logic of racial capitalism, devalues racialized bodies and prioritizes the sustained operations of toxic industries (Pulido 2015, 2017). This is the reality that Exide’s victims face, the terms under which discursive contestation takes place. A mediating infrastructures approach enables us to map this set of power relations onto a broader network of agents, human and nonhuman, and to track how these asymmetries are reinscribed or challenged in the process of (re)mediating the site.

The first mode that Mukherjee elaborates is technostruggle, drawing on a term used by Kath Weston to describe “when people seize upon technology to wrest the production of knowledge from officials and experts” (Weston 2017, 87). The term refers to the mediation of technology that can detect toxicity and produce new knowledge about the infrastructure, as well as the “remediated relationship between expert and laypersons” that follows from that knowledge production (Mukherjee 2016, 103). As the mode that most directly deals with people-to-people or institution-to-people relations, the struggle in technostruggle is readily apparent in the role that Exide’s counterpublic has played in questioning the expertise and authority of state regulators. This is on full display in the twenty-two-minute Los Angeles Times–produced video essay, Unsettled: The Exide Story, which documents the coming together of a lead-toxicity public in various manifestations, from informal backyard gatherings of residents to tense public meetings with representatives of the DTSC. The community’s frustration is palpable in scenes that depict these community meetings, where residents’ questions about who will pay for the medical costs associated with lead poisoning are left unanswered by DTSC’s then director, Barbara Lee (Mollenkof and Bakalar 2015).

The second mode of mediating infrastructures, intermediality, deals with the relations between various media technologies and the infrastructure. In the Exide case, we might expand this mode to include the relation between media technology and environmental medium; for example, the relation between handheld XRF analyzers and the soil they scan for lead contamination. The XRF analyzer, which resembles a barcode scanner like the kind used at grocery checkouts, works by emitting a powerful x-ray beam from the front of the device into the soil sample being tested. The beam displaces electrons in the soil sample at varying rates, depending on the chemical composition of the sample. Through the displacement of electrons, the XRF analyzer can detect the chemical elements present in the sample, as well as the amount of each element, in the form of fluorescent “fingerprints.” Mukherjee argues that attending to this level of relations reveals how “media shift modes of perception” regarding the infrastructure and its toxicity (Mukherjee 2016, 106). For residents surrounding Exide, the confirmation of lead in their backyards, parks, and sidewalks that the XRF analyzer provides certainly shifts their perception of the threat. In 2016, following XRF testing of her property that revealed lead concentration levels as high as 1,550 ppm, Terry Cano, a Boyle Heights resident living within the investigation zone, told the Los Angeles Times that she no longer allowed her ten-year-old son to play in their front yard, “and if he does go outside, he is not allowed anywhere near bare dirt” (Lopez 2016). Unlike in the case of cell antenna publics, who can use aluminum foil to mediate the radiation from cell towers, the price of XRF analyzers (between $15,000 and $50,000) (“Handheld XRF Analyzer Price,” n.d.) precludes residents from independently measuring the amount of lead in their soil, leaving them dependent on the DTSC for testing.

Cano’s fears that the soil would poison her family brings us to Mukherjee’s third mode of mediating infrastructures: affective resonances, “where the experience of engaging with [infrastructure] can be described in terms of affective bodily states” (Mukherjee 2016, 108). Affective resonance can refer to both the anxiety that torments Cano each time her children go outside to play and the absorption of the lead into the bloodstream of Cano and her family, which she suspects is responsible for her various chronic illnesses, as well as her brother Joe Gonzalez’s cancer. Despite the high levels of lead found in the soil samples of Cano’s property, the DTSC’s soil testing method, which takes multiple soil samples from a single property and calculates the average lead concentration, did not find that the property qualifies as part of the 3,200 prioritized for cleanup. As of the writing of this article, it has been five years since Cano learned that the soil on her property is toxic enough to make her family sick, and there is still no telling when the state will be able to replace the soil.

This third mode of mediating infrastructures highlights what Stacy Alaimo describes as trans-corporeality, or the inherent porousness of human bodies that enables interconnections and interchanges with our surroundings. Trans-corporeality thus “underlines the extent to which the substance of the human is ultimately inseparable from ‘the environment’” (Alaimo 2010, 2). Here, we might also return to Pulido’s analysis of environmental injustice in relation to racial capitalism and its “sinks—places where pollution can be deposited. Sinks typically are land, air, or water, but racially devalued bodies can also function as ‘sinks’” (Pulido 2017, 6). Further, Pulido argues that “capitalism functions by restructuring nature. And since humans are nature, we must recognize that capitalism is reproducing itself by restructuring humans on a cellular level” (Pulido 2017, 6). Lead poisoning in children, when it does not result in death, can affect brain development and cause irreversible neurological and behavioral disorders; it is essentially a life sentence, with unknowable repercussions for the victim, the family, and the entire community. This is what makes cases like Exide, or Flint’s water crisis, so incredibly tragic. The poisoning of children is a form of violence that robs the community of its future. Lead poisoning from lead-acid battery recycling plants is therefore an example of what Rob Nixon calls slow violence (Nixon 2011). The slowness of lead’s impact on individuals and communities creates intergenerational trauma, and this trauma ensures the reproduction of social status, keeping poor communities poor by literally altering the physiological constitution of human beings. This is a chilling insight when considered alongside research suggesting that the high rates of crime in the 1970s and '80s were linked to the lead in gasoline and the heightened exposure for inner-city communities of color with greater concentrations of cars and traffic (Drum 2013).

The three modes of mediating infrastructures described above help to delineate the extent of injustice inflicted on the community. They also help us to better read and critique the official mediations of the site provided by the DTSC. Since the start of the testing and cleanup, DTSC has maintained a section of its website for all things Exide, including press releases, reports from the state auditor, and information about past and upcoming community meetings. Often, these documents tell an incomplete story.

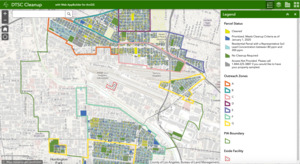

For example, in May 2018 the DTSC created a publicly accessible map to track the project’s progress (“DTSC Cleanup,” n.d.). The map uses different colors to indicate the status of the thousands of properties within the affected zone, marking them as either already cleaned (yellow), prioritized for cleanup (blue), or not requiring cleanup (figure 2). Of that final group, some have had their soil samples test below the safety standard of a lead concentration of 80 ppm as suggested by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (green), while others tested above 80 ppm but below the 300 ppm that the DTSC has established as the threshold for priority status (light blue). Finally, the map is riddled with properties that have not been tested at all (gray), supposedly due to the DTSC’s trouble reaching property owners to request permission to test their soil.

The result is a checkered mosaic that highlights the messy and unpredictable flow of lead particles through the air and soil, a flow that has raised concerns about the potential for recontamination of remediated properties. Against expectation, there are properties on the outer edge of the map that are marked as prioritized for cleanup, while some properties much closer to the plant are marked as having tested below 80 ppm. At the same time, the presence of so many blue and yellow properties on the outer edge suggests that the 1.7-mile radius drawn around the site should be expanded. There is nothing to indicate that properties just beyond the zone, across the street from toxic soil, are not themselves toxic. The size of the investigation zone was determined in 2015 after a preliminary analysis of wind patterns conducted by the DTSC, but there has been no further analysis to determine if the zone should be expanded—unsurprising given the lack of funding to complete the cleanup of the zone already identified. Moreover, the map tells us nothing about the contentiousness of the soil testing process, which was criticized by the deputy director for health protection at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, due to its sampling method of taking the average of multiple samples from a single site (Richard 2017). Although the map exhibits some interactivity, it does not allow users to add any data that might make the map’s tracking of toxicity more complete—for example, there is no mention of the human or nonhuman life that resides on the color-coded properties. By omitting any representation of affective resonances, the DTSC’s map obscures the full harm of Exide’s toxicity.

In direct contrast to the omissions and obfuscations of the DTSC map, there is the Truth Fairy Project, a study conducted by USC researchers and community organizers. In 2014 local community organizations, including EYCEJ, Communities for a Better Environment (CBE), Comité Pro Uno, and Resurrection Church, began holding community-led meetings and workshops in partnership with the University of Southern California Community Engagement Program on Health and the Environment (USC CEPHE), aimed at addressing the inaction of state agencies in relation to Exide. Eventually, this collaboration would result in an advisory group that included elected officials and representatives from government agencies, designed to better facilitate the flow of information between the various stakeholders of the Exide site (or its lead-toxicity public). In 2016 USC CEPHE and its partner community organizations launched a community-engaged research project to measure lead levels in the baby teeth of local children. This study, dubbed the Truth Fairy Project, began from the premise that DTSC’s testing of the soil and the Department of Public Health’s testing of blood lead level were insufficient in demonstrating the extent of the community’s exposure to lead and the resulting health effects. To provide a more complete picture of Exide’s poisoning, the team decided to use a method for measuring in utero and early life exposure to toxic metals by analyzing baby teeth in a laboratory at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York City. Realizing that parents often save the baby teeth of their children as keepsakes, the community organizations conducted outreach through local parent groups to find volunteers willing to provide teeth for lab testing (Johnston, Lopez, et al. 2019, 6). Analysis of these teeth found that their lead levels were twice the amount found in the teeth of a group of children from a similar study conducted in Boston (“The Truth Fairy Project,” n.d.). Moreover, the study found that pregnant mothers exposed to lead could transmit the lead to their unborn children (Johnston, Franklin, et al. 2019). The findings were published in two journal articles and, crucially, were also summarized in bilingual infographics designed to be easily shared and understood by nonexpert residents. As a clear example of technostruggle and the community’s efforts to produce and share knowledge about Exide’s toxicity independent of its enablers, the Truth Fairy Project was able to demonstrate the intergenerational violence inflicted by Exide through an attention to the body’s retention of lead—its affective resonances with the plant.

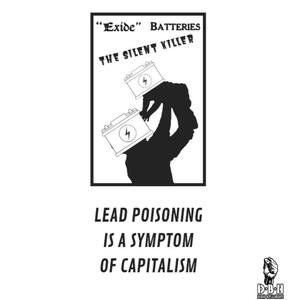

These affective resonances were further visualized in a graphic that circulated on Facebook in 2019 (figure 3). Produced by members of the antidisplacement group Defend Boyle Heights, the image depicts silhouettes of an adult playfully lifting a baby into the air. Where their heads should be, both silhouettes have car batteries. The words “‘Exide’ Batteries, The Silent Killer” are written in a generic horror-movie font above the two figures, and below the image are the words “Lead Poisoning Is a Symptom of Capitalism” in large capital letters (Defend Boyle Heights 2019). The graphic is a poignant illustration of the intergenerational trauma that characterizes lead poisoning. In naming this trauma as a symptom, it also echoes Pulido’s argument about environmental racism as constituent of racial capitalism. Exide’s toxification of Southeast LA was the obvious consequence of a regulatory culture that privileges corporate interests: the result of a working capitalism, not a broken regulatory system.

Conclusion: Sustainability for Whom?

Unsurprisingly, the ways that Exide’s victims experience and understand lead-acid recycling differs sharply from the ways corporations, state agencies, and many scientists do. Lead-acid battery recycling has been championed by some scientists as “one of the first examples of a hazardous product managed in an environmentally acceptable fashion” (Socolow and Thomas 1997, 13). Similarly, the Battery Council International boasts that the recycling rate of lead from 2009 to 2013 was 99 percent, which it claims “show[s] that lead-acid batteries can pass the unwritten specifications of an increasingly environmentally-conscious culture” (“Recycling Rate of Lead from Lead-Acid Batteries Climbs to 99%” 2014). Yet lead-acid battery recycling is frequently ranked the greatest industrial polluter based on global burden of disease and is estimated to put nearly one million people at risk (“2016 World’s Worst Pollution Problems: The Toxics Beneath Our Feet” 2016). In this sense, thinking about Exide’s victims in the context of lead-toxicity publics engaged in mediating infrastructures is productive for enabling transnational lines of solidarity to be drawn between the world’s many communities poisoned by lead-acid battery recycling. This is all the more important given that the Exide plant’s closing in Vernon follows a trend of outsourcing of the industry to the Global South, where regulatory oversight and protection of laborers are even weaker (Johnson 2013).

The contestation among various stakeholders in the case for lead-acid battery recycling as “environmentally acceptable” is indicative of a greater discursive struggle over the terms of sustainability more generally. Scholars from various fields have critiqued sustainability as a discourse, particularly as it has become most closely associated with neoliberal notions of sustainable development (Lee 2012). As the “most globally recognized Earth discourse” (Murphy 2017, 32), sustainable development often continues to frame the environment and development as competing, with economic development, social development, and environmental protection seen as separate considerations (and with economic development invariably receiving priority from corporations, neoliberal governments, and intergovernmental organizations). Nicholas A. Robinson argues that a holistic approach to environmental management is needed to overcome sustainable development’s compartmentalizing of sustainability, which serves to “legitimize existing ‘business as usual’ practices” (Robinson 2012, 183). Similarly, Adrian Parr has warned against the dangers in allowing sustainability to be determined by ecocapitalists, arguing that “the more the power of sustainability culture is appropriated by the mechanisms of State and corporate culture, the more it camouflages the darker underbelly of both—militarism and capitalism” (Parr 2012, 6). For sustainability to be holistic, it must be reconceived in a way that takes into account the multifaceted kinds of injustice that unsustainability has propagated. As Nigel Dower argues, “sustainability involves inter alia sustaining the conditions of justice” (Dower 2004, 399).

Environmental justice, as a framework, emerged partially in response to the limitations of mainstream environmental sustainability. Unlike environmental sustainability, EJ aimed to incorporate an analysis of race, class, gender, and social inequity into its concern with the environment. Consequently, proponents of EJ have often regarded sustainability as the domain of white, bourgeois environmentalists. On the other hand, EJ has been criticized for being overly reactive, focused on “threats to communities” without offering alternative visions for desirable living within the limits of our ecosystems (Agyeman et al. 2016, 328). However, scholars such as Julian Agyeman have argued that a concern with sustainability is not necessarily at odds with the goals of EJ and that a just sustainability framework offers a “middle way between the green/New Environmental Paradigm and the brown/Environmental Justice Paradigm” (Agyeman 2008, 753). Under this framework, conceived as more flexible and contingent than either the traditional sustainability or the EJ frameworks, a centering of social justice and equity meets a desire to imagine a better quality of life within ecosystem limits. Furthermore, this orientation toward the future overcomes the occasionally reactive impulse of some EJ literature and activism.

Given their focus on imagining more equitable futures, just sustainabilities are as much about what we wish to sustain as they are about what must change in order to realize a better quality of life for all (including the nonhuman life that is part of our ecosystems). By drawing our attention to the various publics that form around toxic infrastructure, the mediating infrastructures approach highlights competing notions of what constitutes a better quality of life. The discursive dimensions of material infrastructure and its regulation are thus revealed, as are the grounds of contestation over which forms and visions of life our sociotechnical systems should sustain. In articulating the distinction between mainstream sustainability and just sustainabilities, the dreams and visions of infrastructural counterpublics become critical.

The desire to imagine a better quality of life is clearly expressed in the practices and interactions of the counterpublic formed around Exide. It is evident, for example, in EYCEJ’s launching of the Marinda Pando Social Justice Research Collaborative, a summer program that trains undergraduate students to conduct social justice–oriented research. The project, which began in 2015, is described as “a vehicle to build skill sets in each other for our communities to exercise self-determination” (“2016 Marina Pando-Social Justice Research Collaborative Report 2016” 2016). It is evident in La Cosecha Colectiva, EYCEJ’s decentralized garden project that is “working towards food sovereignty as a real sustainable solution” (“La Cosecha Colectiva” 2020). And it is evident, finally, in the counterpublic’s refusal to accept the terms of sustainability outlined by the DTSC and other state regulators—terms determined by an overwhelming concern with sustaining racial capitalism. Some things are just not worth sustaining.

For a brief overview and scientific analysis of the dangerous levels of lead found around Exide, see Wu and Johnston 2019.

This is likely an extremely conservative estimate of how many people have been exposed to the plant’s toxic emissions, given the high rates of renter turnover in the impacted communities and the fact that the plant spewed toxic emissions for decades (Ross 2020).

There have been no studies on the impact of lead toxicity on the urban wildlife of southeast Los Angeles, and only a few studies in general on lead toxicity and urban wildlife. One such study on lead exposure in the northern mockingbird in three New Orleans neighborhoods found a correlation between high concentrations of lead in the soil and elevated blood lead levels in local birds. The study also found a correlation between elevated blood levels and heightened aggression in the birds, suggesting that lead exposure in wildlife can lead to serious behavioral changes that might have wider ecological implications (McClelland et al. 2019).