Oil accounts for 95 percent of Venezuela’s exports (Tinker Salas 2017, 417). From the birth of the petrostate in the 1950s to the Bolivarian Revolution inaugurated by Hugo Chávez in 1999, petroleum has been mobilized as a political and a social actor in Venezuela’s national imagination. Either as the foundation for unmitigated and fast-forward access to modernity (Blackmore 2017) or as the substrate that would finally deliver on the promise of popular sovereignty and independence from capitalist superpowers, oil has been understood as the structuring substance that sustains Venezuela’s political, social, and cultural life. Despite its ubiquitous presence, Venezuelan studies on oil have been limited to analyses of its technical, political, and economic dimensions. Some notable exceptions are Fernando Coronil’s seminal The Magical State (1997), Martin Frechilla and Texera Arnal’s Petróleo nuestro y ajeno: la ilusión de modernidad (2005), María Gabriela Colmenares’s study on corporate documentary films “La Venezuela rural tradicional según la Unidad Fílmica Shell” (2018), and Miguel Tinker Salas’s volume The Enduring Legacy (2009). While the industry’s social and cultural dimensions have received attention, the environmental consequences of its activities have remained almost absent from public and scholarly discussion (Tinker Salas 2017, 417).

Attention to the visual culture and narratives that emanate from the oil industry tells a different story. Conscious of the disruptions of prior forms of life that they enacted, oil companies operating in Venezuela produced a number of publications and films as part of a public relations campaign that intended to present the industry not only as the harbinger of economic development but also as a promoter of Venezuela’s cultural expressions (Tinker Salas 2009, 196; Barrios 2016, 38). Within this self-assigned role as protectors of domestic social and cultural concerns, the companies also produced articles and features centered on conservation and environmental protection. While these tend to evade questions regarding the impacts of the oil industry itself (Barrios 2016, 40), the ubiquity of these features suggests that anxieties over oil’s ecological impact were not absent but rather were redirected to produce a particular kind of geographical and environmental knowledge. Environmental concerns are equally not absent from Venezuela’s independent visual production. In 1968 Carlos Rebolledo’s eerie documentary film Pozo Muerto (Dead well)—one of the first Venezuelan documentary films and the first one to voice concerns over the legacies of the oil industry—focused on the radical urban and environmental injustices that remained out of sight of oil’s official visual culture.

Grounded in a Venezuelan context, this article centers on the processes of enchantment and disenchantment of oil. Scholarship on the cultural politics of oil emanating from Euro-American contexts has examined how petroleum culture has managed to produce attachments that make thinking beyond it not only a question of finding technical solutions or alternatives to dominant energy regimes, but also a matter of nearly impossible narrative, cultural, and affective disinvestment. Within the emerging field of energy humanities, studies like Stephanie LeMenager’s Living Oil (2014) and Imre Szeman’s individual and collaborative collections on petrocultures have differently demonstrated that fossil fuels have not only produced the means that made twentieth-century progress and development possible, but have also constituted its very substance. Petroleum cannot be extricated from the ways in which the modern subject and the possibilities for its survival are conceptualized. Values such as mobility, speed, autonomy, and belonging—in sum, the structuring values of modernity—could arise precisely because of the capacities that cheap energy affords (Szeman 2019, 10). This body of work positions its emergence from a sense of awareness and urgency upon the twin realizations of having reached the tipping point of peak oil and the moment in which the effects of climate change are most evidently felt. The general impetus in the emerging field of the energy humanities suggests that the Global North has reached a point of no return where, if there is to be any chance whatsoever, disenchantment demands efforts for material and cultural disaffiliation.

How we choose to emplot the stories of oil matters for how we critique its effects as well as how we imagine just transitions. In After Oil, the Petrocultures Research Group acknowledges the potential for contemporary narratives and aesthetics of oil to visibilize what oil seeks to keep invisible. Most importantly, the Petrocultures Research Group takes up the task of forging archetypal narratives for a future after oil. Among these, they propose the fairy tale of transformation as “one archetypal narrative that captures the potential magic of oil and its transformative power, acknowledging oil’s seductive qualities” (2016, 48). With a creative rewriting of the Cinderella fairy tale through the lens of oil, the authors claim that “magic is the energy, the power, and the thing that can transform the mundane into something supernatural, just as it transforms Cinderella to who she is before the stroke of midnight. Oil is the magic that powers modernity. The power of oil is unconscious; we cannot grasp it and we don’t perceive it” (2016, 48). While this is but one of the narratives they propose, the choice is telling for how the temporality of our awareness of oil is envisioned from an Anglo-American perspective. The magic of oil enchants until something breaks its spell—an oil spill, a blowout, global climate change—and it is only then that oil becomes visible.

This article focuses on the specificity of a Latin American and, more precisely, a Venezuelan emplotment of the story of oil. While scholarship situated in the Global North is certainly valuable for the cultural work of visibilizing and dismantling the attachments produced by petrocultural enchantment, attention to views rooted in other extraction enclaves provides a necessary modification to this narrative. From a perspective grounded in the Global South, and the oil-producing Venezuelan context more specifically, the labor of enchanting oil becomes visible. As my analysis of Creole Petroleum Corporation’s media production will show, oil’s magic does not naturally emerge from oil’s material qualities and what it makes possible, but from a conscientious and concerted effort to enchant oil. In this sense, my work is aligned with Mona Damluji’s (2016) analysis of corporate petrofilms in the Iraqi case as an intentional effort to present oil extraction as “a natural process” and to “narrativize the association between neo-colonialist practices of oil extraction and national development as causal, inherent and positive.”

Examining these active processes of naturalization and their contestation in Global South enclaves allows us to question the linearity of petroculture as a process that has enchanted the imaginaries of modernity and is only now revealing itself as a shattered illusion. Attention to sites of extraction where oil development and modernity continue to be seen as a process presents a more complex picture. Enclaves that have been shaped and defined by extraction are sites of contestation where the temporality of the story of oil is not linear but is marked by the interruptions of its boom and bust cycles with their corresponding social, political, and environmental impacts. In the Venezuelan context, the very enchantment of oil becomes a site of visual and discursive contestation.

Visibilizing the booms and busts of the oil industry in zones where it has acted not just as a force of modern development but also as an active propulsor of confrontation and fast-forward upheaval from previous modes of production helps us reframe the temporal and geographic dimensions of both transition and impasse.[1] Rather than considering these concerns as particular to our current cultural moment, visibilizing the history of global zones of extraction suggests that the history of petroculture is from the very beginning marked by a series of uneven transitions, suspensions, and interruptions. Despite the framing of this history through the language of magic, petrocultures are haunted by the disarray that they cause even in the cultural production whose intention is to univocally define territories for their extractive potential.

To complicate the temporality of oil and its enchantments, this article will continue by focusing on the visual culture generated around one of Venezuela’s most prominent extraction sites: the Maracaibo region. Located in the west of the country in the state of Zulia, bordering Colombia, the Maracaibo region is Venezuela’s oil epicenter and main extraction site. Since the discovery of the Mene Grande well in 1914 and, most importantly, the blowout of the Barrosos II well in 1922, the area surrounding Lake Maracaibo became the ground for competition for foreign oil companies, such as Royal Dutch Shell and Creole Petroleum Corporation, Standard Oil’s subsidiary in the country, both of which were granted large concessions by caudillo Juan Vicente Gómez. During the 1930s, Venezuela became one of the world’s centers for oil exports. By the 1940s, the industry’s infrastructural projects and new urban enclaves, together with mass migrations from the countryside, radically transformed the lake and its shores and turned it into what Sean Nesselrode Moncada has called a “paralandscape” of pipelines, derricks, and oil towns (2016, 305). Today, the lake is pierced by more than five thousand inactive oil wells and crisscrossed by fourteen thousand kilometers of pipelines that seep up to twenty-five barrels of crude a day (Figuera 2019), turning the area into “an environmental war zone” (Correa 2016, 68).

The accelerated entrance into petro-industrial modernity and its disjunctions shaped the orientation of Venezuela’s oil-related visual culture. The sudden eruption of a foreign presence that radically transformed the nation’s landscape together with the attempts to reconcile the nation’s agrarian tradition with the futures that oil promised posed a problem for the narrative of fast-forward progress promoted by both the oil companies and the state. The asynchrony resulting from the coexistence of rural cycles and the oil industry, together with a radically shifted demographic landscape of both domestic and foreign migrants who turned to the newly built oil towns to participate in the labor force, marks the nation’s visual and cultural production. Regardless of their intentionality and ideological dissonances, anxieties about the profound demographic and environmental transformations brought about by the petroleum industry permeate both institutional and unofficial media. As they unfold, they contend with the ghostly landscape produced by oil extraction.

Miraculous Mediations: Agrarian Communities and Petro-Industrial Development in El Farol

With the death of caudillo Juan Vicente Gómez in 1935, oil became a central agent in imagining Venezuela’s path toward becoming a modern democratic nation. The role of foreign companies and the distribution of oil wealth were at the center of the debates about democratic nation-building. Negotiating the tensions surrounding the place of foreign companies in Venezuela’s development as a modern oil nation was one of the central programs of the oil industry’s corporate media. Among the many materials produced by the oil industry’s public relations programs, Creole Petroleum Corporation’s magazine El Farol was by far the most long-lived and widely circulated. Creole Petroleum Corporation was Standard Oil’s subsidiary in Venezuela. Together with educational programs, radio shows, and other broadcasting media, El Farol initially circulated among the company’s staff and workers to promote practices and ways of living to ensure employee productivity and affiliation to the policies of the oil companies across the newly built encampments. In a context where Venezuelans were rethinking the role of oil as integral to nation-building and where neighboring nations such as Mexico had nationalized oil, El Farol constituted an intentional effort to present the oil industry as a domestic rather than a foreign presence (Tinker Salas 2009; Nesselrode Moncada 2016). In its early numbers, the magazine was part of the company’s effort to naturalize the foreignness of the oil industry by presenting itself as a bearer of reconciliation where the company would be “a supplier not just of modernity but of tradition as well” (Nesselrode Moncada 2016, 305), seamlessly uniting Venezuela’s past and future. However, this interest in local culture and history is often directed toward a markedly North-American way of life. Part of the enchantment of oil is its promise of transformation from Venezuelan tradition to U.S. modernity.

In its early numbers, El Farol published mostly unsigned features, photographs, and short texts that dealt with the concerns of the oil industry and its global dimensions, a trend that the US Standard Oil magazine The Lamp would follow until it ceased circulating in 2017. Geared toward board members, investors, and employees, these first issues were concerned mostly with questions relating to the various phases of oil extraction and circulation, as well as with the development of infrastructural projects along Lake Maracaibo’s shore. In addition, the magazine included feature articles on the construction of facilities that would traditionally have been the competency of the state, such as roads, schools, and hospital buildings. Specialized scientific features, mostly on biology and geology, also permeated its pages, and, as the population of the oil encampments grew, the magazine also included features on country clubs, baseball, and education programs. During the 1950s and 1960s, El Farol ceased to be akin to the company’s newsletter and became a cultural magazine in its own right. Creole Petroleum hired some of the nation’s most prominent artists, writers, and politicians to serve on the magazine’s editorial board, as well as a number of experts in fields that ranged from the arts to the natural sciences.

The publication’s initial issues function as an archive of visual, narrative, and spatial practices of territorial measurement, control, mapping, and reorganization that sought to visibilize a particular set of transformations while invisibilizing others. Among its varied features on local culture, Creole’s publication stands as a testament to the company’s own practices, documenting its own processes of territorial transformation while channeling local anxieties, feelings of dispossession, and environmental injustice that emerged from its own disruptions. Looking at how petroleum corporate media portrays its role in the modernization and development of Venezuela illuminates how oil companies sought to shape positive affective investments in their presence. Without doubt, the capital city of Caracas was the center for the display of oil’s magic. With “dazzling projects that cast their spell over audiences and performers alike” (Coronil 1997, 5), the capital city became the “storefront” of oil development (Blackmore 2017). Projects like Alexander Calder’s Aula Magna (1953) at the Universidad Central de Venezuela and megamall El Helicoide (1961) dominated the visual field of corporate and state media. Resonant with Damluji’s description of oil-fueled urban projects in Baghdad as tangible images of modernization (2016), the hypervisible and alluring transformation of Caracas also served the purpose of directing the national gaze away from the social and environmental transformations of oil extraction. With extraction zones in the periphery, petromodernity remained at once “extraordinarily tangible” and “unfamiliar,” shrouding oil extraction with a “ghostly aura” (Coronil 1997, 103). The oscillation between hypervisible and invisible processes of modernization suggests that enchantment and haunting are co-constitutive elements of oil modernity. In order to construct the oil as a magical agent, certain local communities had to be visually and rhetorically evacuated.

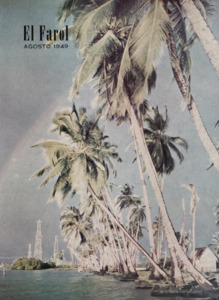

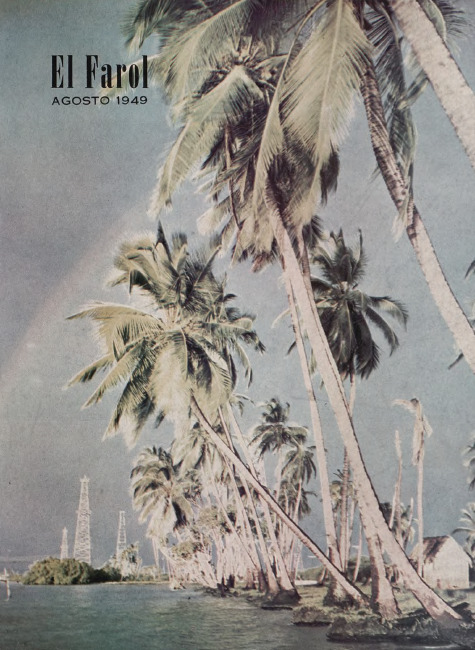

Two El Farol cover features published in 1949 illustrate how Creole Petroleum Corporation sought to use the magazine to naturalize oil and as a performance of territorial management that sought to hypervisibilize its processes while invisibilizing others. In its August 1949 issue, the journal featured “the sharp focus” of National Geographic photographer Ruth Johnson as a commemoration of the colonial encounter with Lake Maracaibo (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1949a).[2] Visualizing Lake Maracaibo as a tropical enclave surrounded by palm trees and positioning oil derricks in a distant background, the color coding in Johnson’s composition renders petroleum infrastructure just visible enough to signal “the industrial progress and mechanization of our century” and to preserve “the polychromous placid landscape of the lake region” (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1949a). Discussing a very similar image that circulated during the 1940s in the national newspaper El Universal, Nesselrode Moncada (2016, 315) describes the conjunction of the derrick and the palm tree as a promise of the metamorphosis that could unite past and future. Uniting the natural world with oil infrastructures, the image works to naturalize oil extraction (Nesselrode Moncada 2016, 315). In its 125th issue in the same year, El Farol featured on its cover a photograph of a young Venezuelan girl in traditional clothing, holding a Venezuelan atlas and a Venezuelan history book. The young girl’s view is directed upward and toward the right of the frame, thus positioning oil extraction as a bearer of a social future that is seamlessly grounded in a Venezuelan tradition and geography. Taken together, these images establish El Farol not only as the mediator of the social promises of the subsoil, but also as the authoritative producer of a unidirectional geographical totality that would be materialized through a particular set of territorial visions and practices.

El Farol’s cover illustrations elaborated a visual narrative that presented refineries, pipelines, and the suburban-style dwellings of the oil camps as the end point of Venezuela’s trajectory. Between these covers, the journal’s pages focused on ongoing processes of building, assembling, and reorganizing that sought to make its audience an active witness of the process. While the color cover and back pages provide visions of the materialization of the promises of oil, El Farol’s pages do not code Venezuelan territories as naturally empty spaces; rather, they are gradually emptied out through the magazine’s visual and textual apparatus. The question then becomes not only the figuring of these territories as terrae nullius for the taking, but how these processes of evacuation were effected materially, discursively, and visually. In its conscious effort to suture its readership through displays of the process of transformation itself, El Farol provides a visual archive of this evacuation that signals its attempt to reconcile the promise of the good life of newly built urban spaces with the displacements of a local, mostly agrarian population.

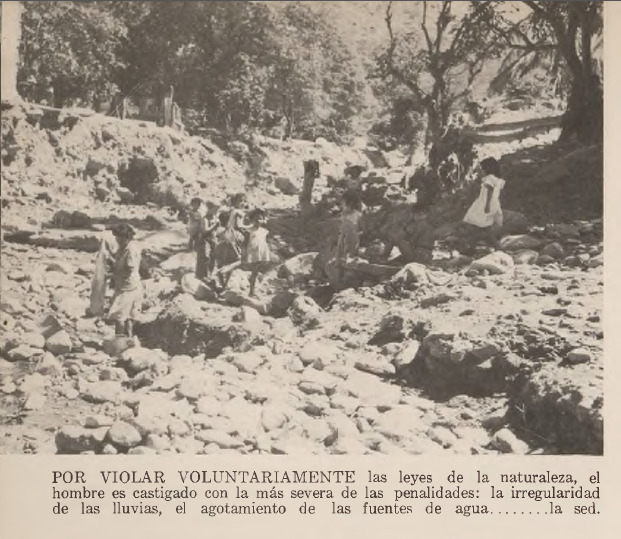

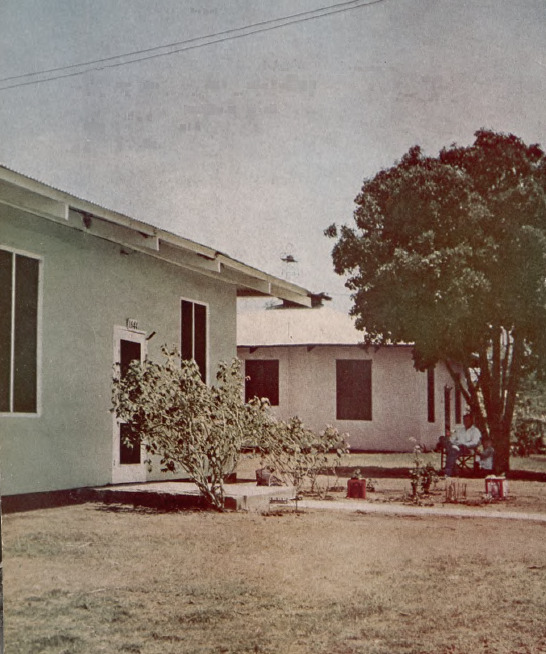

In 1948 and 1949, El Farol featured multiple travel and tourism features, botanical studies of biodiverse regions, and conservationist articles. In two pieces titled “For the Conservation of Our Soil” and “For the Restoration of Our Forests,” the journal documents the agricultural territories of conuqueros, or local farmers. Bemoaning drought and soil erosion, the article calls for a project to relocate these farmers to what it deems more suitable lands, adopting a tone of concern about impending desertification. In captions, the images present apocalyptic notions of anthropogenic environmental destruction, stating that a universal man has “violated the laws of nature” and is now “punished with the most severe of penalties: the irregularity of rain, the exhaustion of water sources… thirst” (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1949b). In the subsequent caption, the article attributes the sterilization of land to the conuqueros as well as to “wood exploiters” and “charcoal producers” who “annihilate all possibility of repopulation” (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1949b). Visually, the images alternate from a group of anonymous children in deserted landscapes who, unlike the young girl in the cover image, seem deprived of any future, to gradually emptier aerial shots of depopulated landscapes. The articles are followed by a piece on a new refinery on the arid Paraguaná Peninsula, featuring the construction of a new pipeline that, as “a miracle of Moses,” would permanently provide water to the residents of the refinery camp. The issue closes with a color image of an irrigated suburban lawn, where a father and son sit peacefully under the shade of a tree.[3] Through this move from images of rural life in sepia tones to color images of suburbia, the conuqueros are visually rendered as relics from the past that have no place in Venezuela’s petroleum futures.

As they visually evacuate agrarian territories through the elimination of human and nonhuman life, these pieces also present foreign petroleum companies as “the miraculous mediator” not only of oil revenues (Coronil 1997, 108) but also of the possibility of life and futurity themselves. As traditional local energy sources such as farming, wood, and coal are coded as threats to sustainability, the journal presents petroleum infrastructures—water pipelines, asphalted roads, and vehicles—and oil as a source of energy as the sole alternative for survival. Through a process that “greens” the benefits of oil and the transition from an agrarian to an industrial economy, conuqueros are coded as threats to futurity itself and are gradually evacuated from these territories, casting these practices as “out of place in a center that calls itself civilized” (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1949b).[4]

Gradually imagining these territories as uninhabited and unlivable, Creole Petroleum argues for the privatization of lands the “state cannot handle on its own” and for the implementation of development programs through Rockefeller’s American International Association for Economic and Social Development. Denaturalizing agricultural spaces and naturalizing newly built oil infrastructures, these features suggest that ecological survival necessarily entails a full transition to an oil energy regime, as well as the displacement of local populations from the spaces now rendered unhomely to the new kind of dwelling offered by the oil towns. Since the topsoil can no longer bear nourishment, it is extraction from the subsoil that can guarantee not only the good life but also life itself.

In these ways, oil’s miraculous transformations produce ghosts. El Farol’s process of visual and spatial evacuation resonates with other instances of energy development across the Global South. Damluji’s (2016) analysis of Iraq Petroleum Company’s visualizations of Baghdad demonstrates how sarifa dwellings were actively avoided in order to present the city as an emblem of oil modernity. In the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s A Persian Story, images of suburbia dominate the film’s visual field as it actively obscures poor living conditions, labor claims, and increasingly polluted environments (Damluji 2013, 84). Similarly, Nixon’s study of megadam development in India demonstrates how to produce a narrative of development whose visual face is that of “spectacular, televisable, soaring feats of world-class engineering” (2011, 151), while local communities become unimagined through processes of visual and imaginative evacuation. “Ghosted communities who haunt the visible nation” (Nixon 2011, 151) are co-constitutive of the discourses of magical, fast-forward development. Across the Global South, energy development is not so much a deliverer of magic as a producer of ghosts. The question is then how these hauntings might be mobilized to demystify oil’s narrative of enchantment.

The Haunted Geographies of Pozo Muerto

I now turn to Carlos Rebolledo’s independent documentary film Pozo Muerto (1968) as an example of a counterdiscourse to the language of magic. Pozo Muerto is the first documentary film to question the legacies of oil in Venezuela. Documenting the living conditions in the outskirts of oil extraction cities, the film elaborates a lingering vision of urban space that challenges the magical narratives of oil. Inspired by María del Pilar Blanco’s (2012) notion of ghost-watching, which treats haunting as a productive way of knowing grounded in complicated hemispheric spatial configurations, my reading of Pozo Muerto suggests that this register disrupts the magical story of an effortless, unmitigated transition to recenter the stories of dispossession that exist alongside oil modernity’s purported success stories.[5] In reading Rebolledo’s aesthetics in Pozo Muerto as a register of haunting, I explore an alternative way of understanding a lived experience of oil that is grounded within petroculture’s extraction matrixes. In demystifying oil’s magic and placing haunting as a generative register, this section constitutes a modest attempt to repopulate the space of vision that the oil industry evacuated through its media apparatus.

To understand Pozo Muerto, it is necessary to situate it as an intervention in the larger ongoing public debate over the consequence of resource extraction development. As a direct result of the transformations of the oil industry, 90 percent of Venezuela’s population presently lives in urban areas (Tinker Salas 2017, 417). The process began during the 1940s and 1950s when oil encampments developed into towns due to a population increase of approximately 130 percent in the preceding decade (Trinca Fighera 2000, 73). The accelerated increase in population also meant the development of informal settlements surrounding what were already segregated urban enclaves. Felipe Correa describes the conditions of these enclaves as a “bipolar urban condition” marked by the incongruity between the “patron-sponsored settlements” and the “entropic settlements” that sustained them through the provision of workforce and services (Correa 2016, 68). While in early issues of corporate media these settlements remain as unimagined communities (Nixon 2011), during the 1960s the consequences of resource extraction development become a central point of debate in both corporate and independent media production.

In 1968, the year of Pozo Muerto’s first screening, El Farol devoted several issues to the question of urban development fueled by oil. If the magazine had carefully avoided mentioning the outskirts of the oil cities during the 1940s, during the 1960s concerns about the urban conditions of the oil encampments in the Lake Maracaibo area became a predominant focus. Titles such as “From the Encampment to the City,” “The Urban Development of Oil Communities,” and “On the Current Conditions and Prospects of the Oil Industry in Zulia”—to name a few examples—dominated the journal’s issues. These pieces reproduce earlier narratives of El Farol, stating that these communities had developed in disconnected and scarcely populated rural areas. The outskirts of the cities are figured as legacies of this past, and their precarious conditions are attributed to the failure of these settlements to “integrate to the general progress of the nation” (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1968a). Yet the preoccupation with urban settlements also reflects the oil industry’s declining interest in the areas of extraction of the Lake Maracaibo region as oil wells became depleted. Geologist Guillermo Rodriguez Eraso, then president of Creole Petroleum Corporation, suggested that development in Maracaibo could be achieved only through renewed concessions that would allow for the perforation of areas of the lake where “oil lies at greater depths” (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1968b). Whether the oil industry is to continue to contribute to the region, Rodriguez Eraso claimed, “only the drill can tell” (Creole Petroleum Corporation 1968b). While the former encampments and surrounding urban settlements are framed as paradoxical problem spaces that haunt Venezuela’s path forward to modernization, the drill, once again, becomes the magical bearer of futurity and livelihood for the Lake Maracaibo area.

The state of the oil settlements also became a central point in the emerging anticolonial discourse in which Pozo Muerto participates. Also in 1968, the well-known Venezuelan anthropologist and historian Rodolfo Quintero published La cultura del petróleo (The culture of oil), which focuses on the coloniality of oil as a cultural and social phenomenon. Quintero devotes a full chapter to the “ciudad petróleo” (the oil city). In addition to tracing the history and social relationships of these settlements, Quintero describes how, once Creole Petroleum Corporation and other oil companies such as Royal Dutch Shell focused on new extraction frontiers and ceased to be interested in the labor force of the Maracaibo Lake area, the oil cities were not only abandoned but also dismantled. Quintero cites contemporaneous news reports where inhabitants of an oil city express concerns over their city’s future: “We don’t want this to be like what has happened elsewhere, where the company strips the doors from houses and facilities […] In the courtyards of ‘La Estrella’ [one of Cabimas’s streets] there’s only disorderly overgrowth” (1968, 66). Another reporter comments on the anxieties of the population: “wherever the oil company goes, everything burns” (66).

Quintero’s anticolonial tone and his description of the turning of resource extraction towns into zones of abandonment and ghost towns is Pozo Muerto’s focus. Collaborating with Edmundo Aray and Antonio de la Rosa, members of the literary and artistic collective El Techo de la Ballena, Rebolledo in this film shares the aesthetic and political concerns of the artistic movement, particularly in its antidevelopment stance and its critique of the world that oil has built. In its visualization of the material processes and effects of extraction that had previously been evacuated from art circuits and collective imaginaries, the film resonates with El Techo’s previous manifestos “For the Restitution of Magma” and “Homage to Necrophilia,” where the group had called for a consideration of the materiality of oil as a substance through an aggressive aesthetic that presented oil extraction as an inherently violent and necrophilic project. In a wider Latin American context, Pozo Muerto emerges with the Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano and the Third Cinema movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and is in conversation with a current that sought to both move away from Hollywood codes of cinematic production and question Eurocentric imaginaries of development that had defined the previous decades.

Shot in Cabimas—the setting of the inaugural Barrosos II blowout and epicenter of Creole’s refining operations—and the neighboring towns of Lagunillas and Tasajera, Rebolledo’s film combines testimonies, shots of ruinous infrastructure, and visualizations of environmental degradation. Resonant with Fernando Birri’s description of the new Latin American cinema as an exercise of “tracing the map as we walked the ground” (quoted in Trabucco Ponce 2014), Pozo Muerto’s alternation of still shots of landscapes with panning shots from a vehicle in movement on encampment roads place the film as an experimental mapping of the uncertain terrains of oil extraction. Designating itself as a “testimony to oil wealth” in its opening credits, the film establishes itself as an on-the-ground exploration of the failed promises and misdirections of petromodernity through a slow, lingering vision of abandoned urban spaces.

The opening sequence in Rebolledo’s documentary immerses the viewer in the dense and dark foliage of fallen trees as it pans through the empty houses of an oil ghost town, obstructing the spectator’s view as it introduces the voice-over of one of the film’s three testimonies. Víctor Gómez, disembodied, recounts his history of arrival from Paraguaná, where his father and mother made a living from agriculture before the building of the Amuay refinery. From there, Víctor tells the story of his relationship with the settlements surrounding the oil encampments from their early years until his present. His narrative is one that, like most stories of migration to the oil towns, begins “with full enthusiasm” and “the goal of making money” but soon becomes a story of multiple occupations—oil exploration, construction, and barber—that start and stop with the rhythms of the oil industry. Víctor’s testimonial ends with allusions to the continuous disenchantments of the oil industry: “The National Guard, snakes, and ghosts are all that live here. This is what they call “half a life,” trying to find money [here] is like trying to find God in the jungle” (Rebolledo 1968). Next, in an echo of El Farol’s initial cover images, the camera cuts to an abandoned school building as the voices of absent schoolchildren resonate through the emptied-out spaces. A singer whistles as the score merges with the voice of one of the children reciting a standard Venezuelan geography lesson: “Venezuela is in South America. It has borders to the north with the Caribbean Sea, with Brazil to the south, to the east with Guyana and to the west with Colombia. It has a surface of almost a million kilometers and its main source of wealth is petroleum.” (Rebolledo 1968).

Through the alternation of Víctor’s testimony and the formulaic geography lesson, the site of extraction becomes one that is simultaneously haunted by past social and environmental histories of dispossession and by national and corporate mythologies of oil wealth. Contrasting with the bird’s-eye view that dominates the visualizations of the encampments in institutional media, Rebolledo’s film mobilizes different kinds of geographical knowledge and self-reflexively signals its own attempts to produce a situated view of the oil town outskirts. As the film retraces the geographical trajectories of the migrations from the rural to urban enclaves produced by the oil industry, it reinserts the histories of past migrations into the oil town. From the ground, the space of the oil town is one that is always already inhabited by those who previously populated it, but also one where the future is no longer directed by the promises of oil’s magic but instead is haunted by it. In this sense, Rebolledo’s film can be understood as an expansion of the “range of visibilities” oil infrastructures allow and an enactment of how its meanings shift depending on one’s positionality. With his on-the-ground view, Rebolledo encodes the oil encampment not as a site of dreams and desires but as one of their suspension (Larkin 2013, 333). Yet Rebolledo’s aesthetics of haunting is also generative. In Pozo Muerto, the combination of these aural elements with visualizations of peopleless, ruined infrastructures questions the legacies of oil wealth and challenges the definition of the territory in relation to its extractive potential. While haunting achieves demystifying oil enchantment, it also leaves Cabimas’s future in suspension. Haunting does not entail resignation or passivity but offers what María Pilar Blanco describes as “a site of action that does not know its outcome or even its purpose” (2012, 25). Extending this to the context of petroleum, this sense of uncertainty that the language of haunting affords is relevant for imagining a temporality of oil that is not based on a magical fast-forward movement. The lived experience of petrocultural development as haunting rather than magic emphasizes that its history is one of struggle, interruption, and impasse, notions that are relevant for the imagination of future transitions beyond oil.

Víctor’s poetic rendering of life in the encampments as half a life is subsequently contextualized through the second testimony, offered by an unnamed journalist from Cabimas. The journalist’s account does the work of situating the city as an emblematic enclave of continued dependency and disenchantment, where the prospect of gaining a livelihood from the activities of the oil industry keeps the population in a state of unfulfilled hope for employment. Instead of hope, dependency keeps the town in a state of suspension and abandonment:

They are packing up their luggage to create pressure, but they won’t contribute to the development of this town. From the moment of the first blowout [Barrosos II] to the moment in which they declared Cabimas’s death, they [oil companies] haven’t contributed to the minimum sign of progress of this community. They might invest again but it might amount to nothing. Cabimas enriched the oil companies and the nation’s coffers, but today they [oil companies] are digging their grave. This town is under a death sentence regardless of its obsession for life. (Rebolledo 1968)

Here, the film enters into Venezuela’s paradoxical relationship to oil. The world of 1967 Cabimas is, in an admittedly narrow sense, a world of what remains after oil. The journalist’s testimonial suggests that life in the city without the activity of oil companies equates to death, yet it argues that dependency on oil will only rob these communities of the possibility of other futures. The shadow of prior magical failed promises of oil looms large over the city’s population and the journalist-analyst himself, as his claims are directed not necessarily toward oil as a substance but toward the colonial relationship between the oil companies and the state. Here, the journalist’s testimonial embodies an instance of what Stephanie LeMenager calls petromelancholia, or the grieving of a modernity that not only “begins to fail” but that never fulfilled its promise in the first place (LeMenager 2014, 104). What is significant here, however, is that this kind of affective disposition not only focuses on a singular moment of rupture or impasse, but also revisits the history of oil in the region as one of intermittent unfulfilled promises from the outset. The “ghost of oil wealth,” as Venezuelan scholar Emiliano Terán Montivani calls the nation’s continued affective investment in oil riches (2014), recurs alongside the booms and busts of the industry. At the same time, the film suggests that throughout these processes of enchantment and disenchantment, new ghost communities are produced. As the journalist claims that the “town is under a death sentence regardless of its obsession for life” (Rebolledo 1968), the film turns to close-ups of the town inhabitants who offer their defiant view to the camera. They do not speak, but their presence serves as a testimonial of the hauntings that the oil industry produces.

The last testimonial of the film comes from Nemesio Hidalgo, a fisherman in the town of Lagunillas. Rebolledo combines shots of the interviewee with the infinitely pierced surface of the lake, where oil derricks extend to the horizon. The fisherman’s story concerns the increasing difficulties of obtaining crabs, shrimp, and fish from the lake due both to a resistance on behalf of the oil industry to allow the activities of local fishermen and to an increasing number of oil spills into the lake: “I can’t even catch crabs. I’m there, enduring the cold all night, until last month, and I didn’t even catch a crab” (Rebolledo 1968). The fisherman’s testimonial also signals environmental concerns as an ongoing struggle between local populations and the oil companies. “When we [the fishermen] made our first complaint, the first oil spill happened. We went back to get shrimp, and the spills came back. […] We made a plan. If we meet or complain they call us terrorists. […] The company might allow us to fish again, but the oil spills won’t cease” (Rebolledo 1968). This testimonial of oil pollution and activism against it is visually interrupted by images of severed plastic mannequins and magazine cutouts of fashion models. Through these sequences, the film continues its work of demystifying the enchantment of oil, this time through an allusion to the senses of desire and futurity that emerge from petroculture. As the film disinvests its viewer from the fantasies of oil consumer culture, it also points at haunting not only as a figurative lingering presence but also as a material one. Discarded plastics and continued oil spills present haunting as more than the return of the past—as a temporal frame that will continue to be haunted by the material disarray of the petroleum industry.

In Ghost-Watching American Modernity, María Pilar Blanco (2012, 28) examines the ghost town as a figuration of haunting. In her argument, the ghost town stands as an emblematic site to explore the contradictions of modernization, as spaces of abandonment that exist in simultaneity with the processes of modernization that respond to an official version of modernity’s success. Blanco argues that hemispheric sites such as the mining ghost town are not to be seen as mere vestiges of the past that haunt the present, but rather as exemplary sites of the “dynamics of abandonment” (79) intrinsic to modernization that reverberates into the present. In interrogating fictional representations of ghost towns, Blanco asks, “how do we construct a reading of haunting that can understand the representation of failure?” (81). The ghost town provides an answer in that, although they are invisibilized or abandoned by the cycles of modernity—a modernity that cannot be extricated from oil—they nevertheless interrupt its narrative of uninterrupted progress. More importantly, Rebolledo’s aesthetics of haunting points toward ghost towns as cyclical processes rather than as finished ones—for those dependent on petroleum economies, the experience of haunting and being haunted becomes the register to understand the lived experience of oil.

Rebolledo’s film, however, also suggests a register where haunting does not signify stasis but produces alternative modes of figuring oil extraction. Throughout the film’s still shots of problematic spaces, Rebolledo slowly pans the camera through dense foliage and utilizes close-ups through depopulated interior spaces save for the ubiquitous scattered leaves and pumpjacks that gradually lose their mechanical movement. During the fisherman’s testimony, Rebolledo slowly pans through the dark surface of Lake Maracaibo and its salient deadened trees, while the camera lingers on images of ruinous pipelines (figure 10). The directionality of the image is significant: while corporate images of pipelines present their direction toward an infinite horizon that colonizes the future, here Rebolledo inverts the image to suggest a questioning of oil futurity. These sightings, coupled with slow movements through space, position Rebolledo’s film as more than a mere description of disarray that surrounds the oil town. Rather, Pozo Muerto presents an atmospheric rendering of crude geographical sensing that generates a problematic yet generative mediation of social and environmental degradation. In these often obstructed visualizations of deserted spaces, the film not only points at the uneven distribution of material disarray of petroleum extraction and lingers on what Tinker Salas has called a “toxic status quo” (2017, 420), but it also slows down the speed and shifts the directionality of oil’s fast-forward modernity. In so doing, it suspends the narrative of oil as the sole bearer of futurity while also potentially opening up a space for imagining otherwise.

Rebolledo’s film inhabits the impasse. In thinking about transitions, the Petrocultures Research Group defines impasse as a moment of indeterminacy where common assumptions no longer hold (2016, 16). Understanding the impasse as a site of possibility rather than blockage, the Petrocultures Research Group suggests that the impasse can be “a space of hope” (2016, 16) where “there is opportunity for breaking with the limitations of that legacy” (16). Venezuela’s haunted emplotment provides a register with which to understand how impasse, and not just magic, can be visualized.

Conclusion

In this article, I have focused on the emplotment of narratives of oil from the position of Venezuela’s oil epicenter. From this perspective, magic is one of the many available registers needed to understand cultural and affective investments in oil. However, to frame oil through the lens of magic is to speak the dominant language of petroculture. In my analysis of El Farol, I show that oil’s magic is neither intrinsic to the substance nor what it makes possible; rather, a discursive labor goes into constructing oil as a magical agent of modernization and development. To sustain itself, the bedazzling discourse of magic needs to produce ghost communities that have found in haunting a productive register to demystify what the oil industry has constructed as its miraculous mediations. Through my reading of Pozo Muerto, I suggest that the lived experience of oil around Lake Maracaibo produces other registers as a way of knowing what it means to live with oil. In the Venezuelan case, both documentary filmmakers and their interviewees find in haunting a modality of narrative that demystifies and registers petroculture’s cycles of dispossession, interruption, and uncertainty.

The resonances between the Venezuelan case and oil extraction enclaves in the Middle East suggests not only a shared visual history of hypervisibility and invisibility across the Global South, but also the possibility of comprehending petroculture as a global discursive field in which the enchanted language of magical futurity is often constituted and made possible through representational and material violence. Haunting—be it as recuperation, as interruption, or as suspension—suggests that experience of oil temporalities in these enclaves can provide wider perspectives to conceptualize the impasses that are now making themselves present in Anglo-American contexts (Petrocultures Research Group 2016, 16). For a conception that sees impasse as “a condition of possibility for action within a situation that is suddenly open because it is uncertain” (Petrocultures Research Group 2016, 16), the Venezuelan case suggests that transition, impasse, and suspension have long been constitutive of the lived experience of oil modernity, thus providing a precedent for thinking about impasses as apertures rather than as paralysis.

Rebolledo’s documentary did not transform Venezuela. The imaginaries of oil’s magic have remained to produce and sustain new enchantments during the Bolivarian Revolution. In an example of petromelancholia, contemporary international media outlets proclaim and bemoan the end of “the oil Giant” (Urdaneta, et al. 2020; BBC 2021). As Venezuela reinvents its extraction frontiers, insisting on dispelling the lure of extractive magic, the careful mapping of its violences and evacuations becomes once again a necessity for a just transition.

Acknowledgments

I thank Janet Walker, Stephan Meischer, Sage Freeburg, and Anthony Greco for their exhaustive feedback and generosity through the various stages of this article. Many thanks to Mona Damluji, Jessica Coyotecatl, and the members of the Re-centering Energy Justice Focus Group for their support during the past three years.

Throughout this article, I use Lisa Blackmore’s helpful term “fast-forward development” (2017) as the characteristic pace of an oil-fueled modernization that displays itself through highly visible infrastructures and public works. The fast-forward pace of modernization also suggests an equally accelerated and active movement toward political and social amnesia (8).

All translations from the Spanish are mine.

Miguel Tinker Salas (2009), Sean Nesselrode Moncada (2016), and Elisabeth Barrios (2016) identify the suburban dwelling and the green lawn as emblematic visualizations of oil’s miraculous promises and as the antithesis of uncivilized, untamed nature (Nesselrode Moncada 2016, 310).

Elisabeth Barrios makes a similar claim in her analysis of Venezuelan cultural production. She claims that insistent presence of images of a “timeless nature” during the first decades of oil development became a strategy to present a narrative that minimized oil’s environmental impacts.

Previous work on Pozo Muerto includes Sean Nesselrode Moncada’s conference presentation “Killing the Well” (2018) and Gianfranco Selgas’s “Testimonios de oro negro” (2020). Moncada’s reading, close to my own, suggests that Pozo Muerto is an attempt to denaturalize petroculture’s visual economy. Selgas focuses on the documentary as an effort to recuperate the lived experiences and memories that remain out of view in corporate and national accounts of oil development.