1. Locating Oil in Santa Barbara County

We climbed a jagged bluff to an overlook where we could watch waves breaking up the coast, offshore oil rigs bobbing on the horizon.[1] It was a bright, brisk day in November. We squinted and shielded our eyes against the reflection of the sun on the water. We had carpooled from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), where our visiting speaker, Timothy Mitchell, would serve as the discussant later that afternoon for a symposium called “Through and Beyond the Politics of Carbon.” That morning, two teams of graduate students led field trips to Refugio State Beach and Coal Oil Point, two sites that are significant to the history of oil in California. Refugio State Beach was our first stop.

As we drove up Highway 101, tightly packed into as few cars as possible, we listened to an audio recording created by the Refugio team. Their narrative drew our attention to the coastline that sped past the driver’s side window. UCSB and its surrounds, stretching north to what is now known as Morro Bay and south to Malibu, are located on the unceded Indigenous lands and waters of the Chumash people—the traditional and expert custodians of the region. Though located on Chumash land, Refugio State Beach’s interpretive markers focus more on the historical drama of French pirates and Spanish “explorers” than on ongoing settler colonial conquest and dispossession.

Refugio State Beach is the site of a 2015 pipeline rupture that spilled more than 142,000 gallons of crude oil into the Santa Barbara Channel, interrupting fisheries and killing scores of marine mammals, birds, plants, and other more-than-human life. As the student audio recording reported, “Humans are not the only animals traveling to and through this corridor.” Despite the pipeline’s recent rupture and ongoing monitoring to understand the spill’s impact on the region, what may be most remarkable about Refugio State Beach is that the 2015 oil spill is absent from its public-facing narrative. When the Refugio team spoke with state park employees and visitors, no one had much to say about it. Instead, the promotional materials for the beach highlight its “craggy coastal bluffs” and recreational amenities: trails, picnics, palm trees. Refugio State Beach’s historical and ongoing entanglement with oil is not an exception in the region.[2] Standing on any beach in Santa Barbara County on a clear day, we can see a line of offshore oil platforms up and down the coast. This is a place where oil was made tragically apparent in 1969 and again in 2015, but it has been extracted, stored, and shipped through the region for over a hundred years.

Often cited as a founding moment of the modern environmental movement (LeMenager 2014; Spezio 2018), the 1969 Unocal oil spill is part of a much broader and deeper story of oil in Santa Barbara County, which has felt the effects of the oil industry since the early twentieth century and continues to be a site of oil extraction and contestation today.[3] This essay introduces A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara, a multimedia narrative and map produced by graduate students in a course conducted by professors Javiera Barandiarán and Mona Damluji at UCSB. It is at once a pedagogical reflection on the project and a critical assessment of the digital field guide as a product of environmental media studies scholarship. As one of the designers of the assignment and as a graduate student who completed it, we as authors have distinct perspectives on the project, while also sharing a pedagogical commitment to place-based, interdisciplinary, and experiential research that leverages the resources of an academic institution while moving beyond its traditional sites: the classroom, the archive, and the often solitary act of writing. We feel that creating the Field Guide offered students the opportunity to collaboratively practice a number of methods from the humanities and social sciences while engaging with energy in the place where they live and work, a place they may be passing through in their time as graduate students, but a place that might nonetheless be instructive as they consider their relationship to land, energy, and power wherever they find themselves. Our experiences with place-based and site-specific pedagogy taught us how collaborative research can itself be a form of community-building across disciplines.

This essay also offers recommendations for others interested in crafting similar projects. The following questions guided this work: What does site-specific, interdisciplinary, multimedia research on energy justice look like?[4] What are its benefits and challenges? What are the best platforms for presenting this kind of work? While acknowledging its experimental nature, this essay also explores how the Field Guide is a model for interdisciplinary pedagogy and practice in environmental media studies.

Both the Field Guide and this introduction are born from a multiyear collaboration, supported by the Mellon Sawyer Seminar on Energy Justice in Global Perspective, among graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, Mellon Sawyer faculty, seminar speakers, and campus and community members and activists focused on energy justice in the Santa Barbara region and beyond. While traditional academic writing collapses the process of collaboration into a single authorial voice on the page, we have striven to preserve the polyvocality inherent to this project—multiple voices and perspectives are interwoven throughout each site of the Field Guide and are joined here in this coauthored introduction. As an inherently collaborative project, we assert that the kind of slippery interdisciplinary work the Field Guide is committed to requires on- and off-campus community collaboration, and as such, we have worked to ensure that we do not reduce narratives about or analyses of oil in Santa Barbara to a single flattened voice, instead favoring the more nuanced and complex multiperspectival narrative made possible by collaboration (Mellon Sawyer Seminar on Energy Justice in Global Perspective 2019a).

2. The Making of the Field Guide: Environmental Media Pedagogy

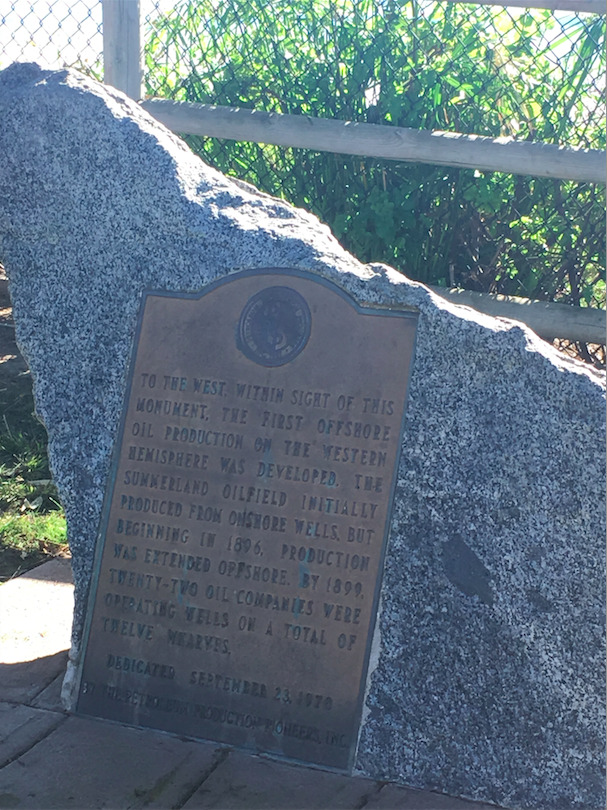

A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara is a multimedia narrative and map built with the web publishing platform Scalar.[5] Over the course of the fall 2018 seminar—which provided epistemological scaffolding for applying an energy justice approach to engaging with one’s own region—graduate students from a wide range of disciplines worked in groups to conduct site-based research on the history and politics of oil in Santa Barbara County. They focused on five sites: the Carpinteria Tar Pits, Summerland, the Santa Barbara Harbor, Coal Oil Point, and Refugio State Beach. Inspired by both the spatial and the infrastructural turns in media studies, Barandiarán (Global Studies) and Damluji (Film and Media Studies) asked students to visit their assigned location, conduct archival research on its history in relation to oil, and consider the site from at least three perspectives using a broad range of methods from the humanities and social sciences.[6] Some of the perspectives taken up included those of fisherpeople, Indigenous communities, environmental activists, policymakers, oil industry representatives, and marine animals. At the end of the term, each team facilitated a guided tour of their site for local and visiting Mellon Sawyer Seminar participants.

In addition to leading field trips, each group produced a digital portfolio that contained contemporary and archival images of the site, scans of archival documents related to its history, an annotated bibliography and observational and historical site descriptions. These materials were selected and organized by Mellon Sawyer Seminar Postdoctoral Fellow Emily Roehl, who published them online as A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara. The Field Guide supplemented a series of events in 2019 that marked the fiftieth anniversary of the 1969 Unocal oil spill in Santa Barbara.[7] The Field Guide was first shared with the public at a multimedia exhibition that kicked off the Mellon Sawyer Seminar’s “Beyond the Spill” symposium in January 2019, which also featured archival footage from the 1969 Unocal oil spill and the work of media artist Brenda Longfellow. Exhibition visitors were invited to play Longfellow’s interactive, gamelike documentary Offshore,[8] which explores an offshore oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico through documentary film clips. At the same event, visitors could tour the county by navigating through the Field Guide, which was set up on a number of computers in the exhibition space. The Field Guide served as a bridge between the archival footage and Longfellow’s interactive documentary, providing deeper context for the historical material while highlighting the contemporary traces of oil in the region, alongside and against dominant narratives that contain oil as a part of the region’s past.

By offering a map-based tour, various visualization tools, and metadata search routes, Scalar provides the viewer with a range of options for engagement. The most straightforward way to interact with the Field Guide is to follow the path laid out on the map on the main page, which takes the virtual traveler from the Carpinteria Tar Pits up Highway 101 to Refugio State Beach with stops along the way at Summerland, the Santa Barbara Harbor, and Coal Oil Point. The map is one of Scalar’s built-in themes, and it was well suited to our site-specific project. Exploring the Field Guide by using Scalar’s search function is another way to explore the project. The search function offers the most unexpected discoveries and connections between sites, stakeholders, and histories. By clicking the magnifying glass at the top of any page, users can perform keyword searches and create a unique, idiosyncratic path through the material. The search function accesses the metadata for each item; titles, dates of publication, and locations are all potential search terms. The map theme and the path created between the five sites present a linear narrative of oil in the county, geographically if not chronologically. Navigating via search terms allows users to jump more freely through the material and observe the emergence of common themes and connections across sites: ecology, labor, industry, history, and sensory experience.

3. Dominant Narratives of Oil: Doing Place-Based Research in an Oily Region

The contemporary Santa Barbara region—both in representation (for example, at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum) and physically/ecologically through environmental conservation and restoration at sites like Coal Oil Point—has been constructed in a manner that naturalizes and historicizes oil extraction. For example, the dozens of derricks and offshore drilling piers erected along Coal Oil Point’s bluffs in the 1920s have been decommissioned and since removed, and the site is chiefly known for its snowy plover conservation efforts. Now, only Platform Holly (currently in the process of being decommissioned) jutting out against the horizon and the many tar balls on the beach and in the waves mark Coal Oil Point’s deeper historical and ongoing imbrication with oil and its unjust social and environmental consequences. The construction of oil extraction as historical and natural creates a linear narrative of settler colonial extraction-fueled development that, in its teleological march toward progress, both justifies and contains the region’s historical and ongoing extractive entanglements: when the region’s now sweeping beaches were home to hundreds of jutting oil piers; how Union Oil, responsible for the 1969 Unocal oil spill, brought in incarcerated laborers from San Luis Obispo, Santa Clara, and San Diego to perform the toxic task of cleaning up Santa Barbara’s beaches after the spill (LeMenager 2014, 60–61); the costs local workers and habitats (such as Santa Barbara’s fisheries and the local fisherpeople who rely on them) pay each time a pipeline ruptures.

In their current iterations, each of the five sites that the Field Guide features—the Carpinteria Tar Pits (at Carpinteria State Beach), Summerland’s Lookout Park, Santa Barbara Harbor, Coal Oil Point (a UCSB-managed nature reserve), and Refugio State Beach—is now a place of public recreation. As Field Guide researchers found again and again, these public sites carefully construct the narrative of their relationship to oil extraction as a naturalized thing of the region’s past. Whether at sites such as Rincon Island—the artificial island constructed in 1958 for oil well drilling in Ventura County, just south of Santa Barbara County off Highway 101, which Sawyer seminar participants were able to visit during its ongoing decommissioning by the State of California—or at sites like the Carpinteria Tar Pits and the Santa Barbara Historical Museum, oil is presented as part of the region’s history, with little attention paid to its ongoing afterlives or to the larger human systems of power it fuels. For example, the Santa Barbara Historical Museum mentions oil only in the past tense, recollecting it as part of the region’s history, not its ongoing present. Traces of the region’s entanglements with oil appear in the museum’s archives about the history of the Santa Barbara Mesa (Santa Barbara Historical Museum 2016)[9] and Stearns Wharf (Santa Barbara Historical Museum 2015).[10] In both instances, oil is “discovered” and extracted in the past, as one point on the region’s linear timeline of development and settlement. The historical museum did hold an event focused on the fiftieth anniversary of the 1969 Unocal oil spill (Santa Barbara Historical Museum 2019),[11] but again, this event served as a reflection on the history of oil in the region. Oil is not obscured but is narrated as either a thing of the past (i.e., part of the region’s history but not ongoing) or as “natural” (which in turn obscures and naturalizes the systems of power, extraction, and colonialism that oil fuels).

Carpinteria State Beach’s brochure and signage also present tar and oil as part of the site’s history, safely and cleanly contained in the past (Carpinteria State Beach 2014).[12] At the Tomol Interpretive Play Area, part of Carpinteria State Beach just north of the tar pits, the beach’s tar is celebrated as part of the region’s Indigenous Chumash past. While the play area signage remembers the beach as a site of tomol (a plank-built seafaring canoe) fabrication, it glosses over the violence of Spanish conquest (enshrined in the beach’s Spanish name, La Carpinteria, or “the carpentry”) and the ongoing colonial present. Instead, the play area encourages visitors to “play Indian” (Deloria 1999), making a game of Chumash culture. Presenting the use of the site’s tar (whether by the Chumash, or later, by settler colonial asphalt miners) in the past also traps the region’s Indigenous peoples in the past. Similar to the ways the only mentions of oil at Refugio State Beach are carefully crafted messages about the presence of naturally occurring tar on the beaches, this entrapment not only “naturalizes” settler development and presence in the region through logics of genocidal teleological linearity, but also works to justify large-scale settler extraction—since the tar “naturally” occurs at the site and has been used by humans for millennia. Importantly, the site’s status as a state beach means that the area’s natural and cultural resources are protected by law, making it illegal for tar to be removed or disturbed, ignoring today’s Chumash and their ongoing cultural and technological uses for the beach’s tar (for traditional handcrafting of tomols, basketry, and more). This reifies a Western model of environmentalism that imagines humans as somehow separate from nature; erases the differences between Indigenous and settler-extractive relations with the land and water; and makes invisible both the ongoing presence of the Chumash and the afterlives of colonial extraction in the region.

The Maritime Museum, located at the Santa Barbara Harbor, is one notable exception to the general narrative found at the Field Guide’s other sites. The museum’s exhibit History of Oil in the Santa Barbara Channel highlights that oil has been part of the region’s maritime history for thousands of years, also acknowledging that “today, oil affects every facet of our lives” (Santa Barbara Maritime Museum 2021).[13] The History of Oil exhibit also features photographs and information about the 2015 Refugio oil spill, placing its environmental destruction alongside the more visible and spectacular 1969 Unocal oil spill, and filling in the narrative erasures Field Guide researchers found at Refugio State Beach. In this vein, the public beach at Summerland features signage warning of oil on the beach and its health impacts, presenting a different narrative than the other beaches in the region—one that both recognizes oil’s contemporary presence and admits to its ongoing impacts. The Field Guide, while recognizing that not all visualizations are equally legible, works to enlarge the footholds Summerland and the Maritime Museum provide in the prevalent narrative containment of oil in the region, reading these traces against the dominant construction of oil as natural and trapped in the past.

As many energy humanists have noted, “energy systems are shot through with largely unexamined cultural values” (LeMenager 2014, 4). Furthermore, oil is a slippery substance that moves through a diffuse network of extraction, distribution, and use that, some scholars argue, resists representation (LeMenager 2014, 13–14; Petrocultures Research Group 2016, 45–49). As such, the study of oil and the complex cultural, political, and economic systems it fuels requires an approach that asks scholars to resist traditional disciplinary enclosure and its methodological limitations. One of the strengths of the Field Guide’s multidisciplinary, place-based research was the way it challenged students to question dominant histories and representations of oil as natural or always already historical and to tell alternate narratives. For example, in order to both work against the absence of on-site information about the 2015 Refugio oil spill and to offer a multispecies account of the site, Sage Gerson prioritized methodologies of imagination and speculation, storytelling and narrative, to create objects for her digital portfolio that engaged the experience of more-than-human life and their experiences of the spill.

As part of the research team working to tell a complex, multiperspectival account of Refugio State Beach’s entanglement with oil extraction, Gerson emphasized the 2015 spill’s impact on seagrasses, kelp, marine mammals, and seabirds. Employing imagination and storytelling as methods for engaging with place-based research helped her work against the lack of public-facing information about the spill, preserving the memory of events and highlighting voices and perspectives absent from the official historical record. At the time of her research (2018), Gerson found that the 2015 spill was too recent to have been represented as a historical event but had also simultaneously begun to fade from memory. While state park employees and signage did not acknowledge the spill, Gerson found that the 2015 spill had also not yet entered the region’s local archives—bringing to the fore questions about both the temporality of environmental violence[14] and archival/historical temporalities.[15] Thus, though human imagination and storytelling are unable to fully communicate or capture the experience of more-than-human life, prioritizing these fictive methodologies allowed Gerson to engage with the 2015 Refugio spill in a manner that circumvented archival temporality and on-site erasures. Instead, the Refugio team was able to produce alternative narratives, which they featured in their live guided tour of the site and referenced in their audio recording introduction, that centered the cost and consequences of oil extraction on more-than-human life.

Through multidisciplinary and speculative work like that undertaken by Gerson and the Refugio team, A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara follows the ongoing traces of oil and its afterlives in the region, contextualizing its deeper historical and ongoing imbrication with oil, and working to bring the region’s oily sites and stories to the fore of the Santa Barbara experience beyond dominant narratives that contain oil in the past.

4. The Field Guide as Environmental Media Practice

The term “field guide” usually describes a publication used in the natural sciences to identify and categorize objects or entities, be they plants, rocks and minerals, or animals. Field guides are commonly illustrated, with macro and micro depictions of their objects of study. They work to enable in-the-field identification for both the public and experts alike. Field guides, like maps, operate like a material index of the places or objects they catalogue. Field guides carefully arrange places and resources, going beyond simply describing or portraying a region to order space and relations, and in many cases to facilitate extraction.[16]

Field guides have been used by governments and industries to survey, lay claim to, and extract resources. For example, while researching the history of oil in California, Emily Roehl came across a guidebook to field trip routes produced for the 1952 Joint Annual Meeting of petroleum geologists, economic paleontologists and mineralogists, and exploration geophysicists in Los Angeles at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History library sale (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, and the Society of Exploration Geophysicists 1952). The Guidebook provides region-by-region and mile-by-mile descriptions of the petroleum geology of California and contains descriptions of “some of the most petroliferous areas of California” (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, and the Society of Exploration Geophysicists 1952). Participants at the 1952 meeting took driving tours to visit these locations, which are described and illustrated in great detail in the guidebook. To aid the visitors in their automobile journeys, the field guide also includes foldout and inserted maps as well as a mileage accumulator tool.

Most of the descriptions in the Guidebook are technical in nature, commenting on geography, stratigraphy, roads and bridges, and other points of interest one might encounter along the route. In the section “Ojai to Ozena,” the Guidebook offers the pronunciation of Ojai, noting, “The name is from an Indian word meaning ‘the nest’” (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, and the Society of Exploration Geophysicists 1952, 77). This passing reference to the Indigenous inhabitants of what is now called California is remarkable in that it is a rare historical interruption of the geological and economic narrative of the Guidebook. Ojai, like much of the Central Coast of California, is Chumash land, though this is a story that the Guidebook carefully contains in this single sentence. The reference to cultural, linguistic, and Indigenous history in the Guidebook is a crack in the field guide form that the Mellon Sawyer Seminar participants sought to expand.

The use of oil-powered vehicles to survey the “petroliferous”[17] regions of California at midcentury comes as no surprise, though it was also the case in UCSB’s Mellon Sawyer Seminar that students had to drive to and from their sites in their own fossil-fueled vehicles to conduct research. Students also relied on digital infrastructure, including a complicated web of material technologies and energies, from the servers that support web archives and the Scalar platform to the electricity required to power a cell phone or a computer.[18] What they produced in that process, however, is far from the technical, extraction-oriented documentation of the Guidebook. Mellon Sawyer Seminar participants “hacked”[19] the Guidebook form and instead produced a field guide to oil that works to problematize colonial and capitalist accounts of the region’s resources as readily available and easy to extract.

Over the past decade, field guides and other spatial forms of art practice and public pedagogy have emerged across the humanities and social sciences.[20] For example, groups like the Los Angeles Urban Rangers have offered infrastructure tours that illuminate the ecological and social histories of the built environment.[21] In a similar vein but with more explicit political aims, artist and cyber activist Ricardo Dominguez, working with members of the Electronic Disturbance Theater, created the Transborder Immigrant Tool. This cell phone app for immigrants crossing the US-Mexico border combines GPS navigation with recordings of poetry, providing the location of water caches and offering users the option of listening to poems of welcome that offer information for surviving harsh desert environments.[22] In each of these cases, mobile media (the guided tour, a cell phone app) intervened in participants’ perception and embodied experience of a place while critically interrogating the social and cultural constructions that contour space.

The Field Guide aims to be a public-facing multimedia tool for identifying the history and ongoingness of oil in the Santa Barbara region. Field guides are also mobile and can easily be carried into the field by naturalists or geologists. The seminar participants and Field Guide researchers were not natural scientists, but they were nonetheless looking for traces of a phenomenon—the oil industry—in a place where it has a long, complex, and carefully constructed history. The field, as we defined it for this project, was all of Santa Barbara County. Ultimately, Mellon Sawyer Seminar participants created a public-facing, mobile, virtual guide to five locations that accounted for local history and geography as well as the ecological and social consequences of oil at each site.

The Field Guide is built from the embodied experiences of our multiple site visits and tours, and in turn, it hopes to shape the embodied experiences of its users, as it can be viewed on mobile devices by anyone navigating the region. While the digital product is ostensibly placeless,[23] it could not have been produced without our physical presence in the region or the material technologies and energies that support its digital archive and interface. Engaging with the digital field guide invites the viewer to conceive of Santa Barbara County as one local node in a globalized network of energy production, distribution, and consumption. The Field Guide can also be conceived of as one node in the larger global, material, and environmental network that makes the digital world possible. Importantly, the Field Guide—as context, multimedia guide, speculation, and index—works against the narrative of oil in the region as already concluded history (instead of ongoing) and/or as a natural (not also cultural) phenomenon. Instead, it aims to reshape how locals and visitors alike travel through, dwell in, and understand the region and conceive of their own relationship to oil’s global system. Understanding a region’s co-constitutive history with oil production provides a foothold in the larger slippery global system of oil extraction, refinement, transportation, and use.

5. Challenges and Opportunities

One of the lasting effects of the Field Guide has been on the research trajectories of those involved in its making. For example, as a graduate fellow with the Mellon Sawyer Seminar, Gerson reflects that creating the Field Guide afforded her interdisciplinary epistemological and pedagogical training while also fundamentally shaping her academic path. The experience influenced her subsequent research and teaching in three major ways: (1) the site-based research projects and subsequent creation of the Field Guide encouraged her to engage with the region where she lives and studies in a scholarly manner. Understanding the Santa Barbara region’s co-constitutive history with oil production provided a foothold in the global system of oil extraction. (2) The slipperiness of oil, and the way its diffuse network of extraction, distribution, and use are conceptually difficult, requires nontraditional and interdisciplinary scholarly methods. Participation in the Mellon Sawyer Seminar taught Gerson that knowledge about energy systems must be produced through the employ of multiple, and often nontraditional, methods—encouraging her to resist the limitations of traditional disciplinary boundaries and instead to embrace an inherently interdisciplinary approach to the analysis and study of energy and the complex cultural, political, and economic systems it fuels. (3) Finally, it taught her to incorporate embodied experiences and site visits into her own pedagogical practice. Her work on the Field Guide showed her that site visits can act as course capstones by taking students out of the classroom and providing an opportunity for them to engage with themes and questions from the course in an embodied manner. Including site visits and field trips alongside other pedagogical commitments enables students to engage in multi- and extrasensory embodied experiences that might not otherwise be supported in typical humanities and social science classroom-based learning.

A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara would work well as a model for a capstone project in a six-month or yearlong course. This time frame would give participants the time to fully develop their ideas, have critical discussions about power and privilege in site-based inquiry, and learn new skills to support their research. If the project is ultimately conceived of as for the larger community (in addition to the local campus community and/or a wider community of scholars), a best practice would be to engage with community members early in the process and invite local stakeholders to help shape the research questions and perspectives pursued by field guide researchers. This approach was adopted in the third quarter of the Mellon Sawyer Seminar conducted by professor David Pellow, which focused on “participation.”[24] Combining both quarters’ commitments would make the ultimate field guide a more powerful activist tool for local folks as well as scholar activists. Ultimately, the Field Guide presented Mellon Sawyer Seminar participants with a challenging set of archival, observational, and media-making tasks. Many students carried the research they began for the Field Guide into future projects. As this stream of Media+Environment shows, some of this work has been translated into scholarly writing. In some cases, it has reinforced activism and work people had already been doing with environmental NGOs while strengthening relationships between UCSB and community organizations.[25]

The Field Guide was an experiment in research and pedagogy that hacked the guidebook to provide multiple access points to the complicated history and present reality of oil in a particular place. While the project was focused on five distinct sites in California and coincided with the widely recognized 1969 Unocal oil spill anniversary, it was ultimately designed with the hope that it would inspire similar investigations of energy in places with their own unique histories. Fundamentally, A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara encouraged participants to embrace a “feral” approach to research (Chen 2012, 18). With the Field Guide, Mellon Sawyer Seminar participants sought to expand people’s sense of the deep imbrication of oil and everyday life in the Golden State; to tell complex, multiperspectival accounts of specific sites’ entanglements with oil extraction; and to provide a route into the story of oil in California that reached back much further than the well-known 1969 Unocal spill. A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara works to bring these stories to the fore of the Santa Barbara experience, highlighting and dwelling in the region’s “petroliferous” history and its ongoing consequences.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the five Mellon Sawyer Seminar on Energy Justice in Global Perspective faculty PIs, Javiera Barandiarán, Mona Damluji, Stephan Miescher, David Pellow, and Janet Walker, for their mentorship and support. We would also like to acknowledge and express our gratitude to the graduate students who conducted research and created content that contributed to A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara, including Brett Aho, Stephen Borunda, Ry Brennan, Sandy Carter, Sylvia Cifuentes, Jéssica Malinalli Coyotecatl Contreras, Anthony Greco, Theodore LeQuesne, Sarah Lerner, Christopher McQuilkin, Mary Michael, Nicky Rehnberg, Ariana Salas-Castillo, and Mario Tumen. Finally, we would like to extend our appreciation to the many speakers, activists, creators, and scholars who shared their research and wisdom as participants in Mellon Sawyer Seminar conferences and symposia.

Our use of “we” refers to both the community of scholars who contributed to the Field Guide and our shared interests in the energy humanities, environmental justice, and place-based research, and to the coauthors of this collaboratively written introduction, Emily Roehl (2018–19 Mellon Sawyer Seminar Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, Santa Barbara), who produced the Field Guide on Scalar using material created by the participating graduate students, and Sage Gerson (2018–19 Mellon Sawyer Seminar Graduate Fellow), who took part in the seminar and completed the assignment.

Our use of “entanglement” draws on Nicole Starosielski’s (2016) understanding of infrastructural entanglement and Karan Barad’s (2007) work on the entanglement of matter and meaning. Notably for this introduction, Barad’s definition of entanglement indicates “to lack an independent, self-contained existence” (2007, ix).

We refer to the 1969 spill as the Unocal oil spill throughout to directly assign responsibility for it. In doing so, we follow the lead of environmental activists such as Annie Leonard (of Greenpeace) who also calls the event the “Unocal oil spill.”

There are many terms used to describe the kind of interdisciplinary, multimedia research conducted for this project. Each set of concepts has its own disciplinary and institutional genealogy. A selection of relevant terms includes the following: interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, more-than-disciplinary, undisciplinary, and “feral” (Chen 2012, 18). Multimedia research informed by artistic practices also has a raft of terms: arts-based research, social practice, and research-creation. For more on research-creation and the intellectual and institutional stakes of defining the terms by which we do this kind of research, see Natalie Loveless (2019).

Scalar was created by the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. A number of excellent digital publications have been produced with Scalar, including Pathfinders (2015), on the experience of early digital literature, and Performing Archive (2018), which critically assesses the archive of photographer Edward S. Curtis. For researchers interested in exploring other platforms for this kind of work, especially work among Indigenous communities, we recommend Mukurtu, which was developed by the Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation at Washington State University to provide varying levels of access in order to ethically share and store Indigenous digital heritage: https://mukurtu.org.

The spatial and infrastructural turns in media studies pivot from the theoretical interventions of the cultural turn in geography (Tuan 1977; Soja 1989) as well as postcolonial scholarship on space and empire (Chakrabarty 2000). Media scholars working in this vein draw attention to the geography and materiality of media, whether by analyzing media representations of space or approaching media infrastructure as material worthy of analysis as media (Parks and Starosielski 2015; Starosielski and Walker 2016). Barandiarán and Damluji crafted an assignment with a public-facing outcome that critically engaged with the history and geography of the place where they do their research and teaching: the Central Coast of California.

There were many local community and campus events reflecting on the fiftieth anniversary of the 1969 Unocal spill. These events coincided with, framed, and helped contextualize the launch of the Field Guide. Some of these events included the launch of the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum’s newest permanent exhibit, History of Oil in the Santa Barbara Channel; the UCSB library’s exhibition Anguish, Anger, and Activism: Legacies of the 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill and its companion exhibition Oil Slick, 2019; the Mellon Sawyer Seminar’s “Beyond the Spill” symposium; and the community event “50 Years after the Santa Barbara Oil Spill: A Call to Action.”

To view Brenda Longfellow’s interactive documentary Offshore (2013), visit http://offshore-interactive.com/site/.

To read more about the role of oil in the history of the Santa Barbara Mesa, visit this page on the Santa Barbara Historical Museum’s website, originally published in 2016 in the Santa Barbara Independent: https://www.sbhistorical.org/the-mesa/.

To read more about the history of Stearns Wharf, visit this page on the Santa Barbara Historical Museum’s website, originally published in 2015 in the Santa Barbara Independent: https://www.sbhistorical.org/the-recent-history-of-stearns-wharf/.

To read more about the Santa Barbara Historical Museum’s event marking the anniversary of the Unocal oil spill, visit https://www.sbhistorical.org/event/1969-the-santa-barbara-oil-spill-birth-of-the-environmental-movement/.

For more information about Carpinteria State Beach’s brochure, you can access a PDF version here: http://www.parks.ca.gov/pages/599/files/CarpinteriaSBWebLayout2014.pdf.

For more information on the Maritime Museum’s exhibits, visit https://sbmm.org/exhibits/.

This disconnect drew her attention to how, as Rob Nixon has detailed in his book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Nixon 2011), conceptions of violence often rely on the spectacular (the blowout itself), while the slow violence of continued environmental impact remains invisible.

Gerson’s group had initially wanted to map specimens of lichen in UCSB’s Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration (CCBER) database collection in hopes of noting the spill’s effects on impacted lichen. However, at the time, the most recent lichen specimen collected in the Santa Barbara area was collected in 2014, before the Refugio Oil Spill.

For more on the ways mapping practices contour space and relations, and the way settler colonialism depends on the “sorting of space based on ideological premises of hierarchies and binaries” and “naturalizing geographic concepts and sets of social relationships,” see Mishuana Goeman’s (Tonawanda Band of Seneca) book Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations (2013, 2).

We borrow this term from the introduction to the Guidebook (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, and the Society of Exploration Geophysicists 1952, 7).

For more on the materiality of digital media, see Peters (2016) and Starosielski and Walker (2016).

Our use of “hack” is, in part, a reference to Andrea Polli’s work, “How to Hack the Grid.” She urges her readers to think about the “original definition of ‘hacking’: to make your own” (2018, 1). Her goal, like ours, “is for you to understand more about the energy you consume, to ‘make it your own’ by experimenting with energy-related technologies and ideas, and to be able to make more informed choices and advocate for the kind of energy you want in your homes and communities” (Polli 2018, 1). Our use is also shaped by LeMenager and Stephanie Hoot’s opening editorial for the inaugural issue of the environmental humanities journal Resilience, where they employ the concept of “hacking” to describe their goals for the journal and its title (LeMenager and Hoot 2014, 4).

In addition to the artist projects described here, there is wonderful scholarly and community-based work that has come out since we began this project, such as the work collected in Aikau and Gonzalez (2019).

The Los Angeles Urban Rangers create “guided hikes, campfire talks, field kits, and other interpretive tools to spark creative explorations of everyday habitats” (“Los Angeles Urban Rangers,” n.d.).

More information about the Electronic Disturbance Theater, recently reimagined as EDT2.0, can be found online at http://www.thing.net/~rdom/ecd/EDTECD.html.

The digital infrastructure required to support the Field Guide is, of course, not placeless at all but relies on technologies that occupy material places, from servers to cables to electrical grids.

More information about the yearlong series of seminars, including Pellow’s course on participation and the course syllabi, can be viewed here: https://energyjustice.global.ucsb.edu/seminar.

The spring quarter of the Mellon Sawyer Seminar resulted in research deliverables that supported anti-extraction activism throughout the region. It had a twofold pedagogical purpose in that it trained early career scholars to engage in scholar activism while also preparing them to teach their own current and future students about scholar activism. The Mellon Sawyer Seminar fellows also produced a webpage that introduced participants to local energy justice struggles. This work can be viewed here: https://energyjustice.global.ucsb.edu/activism.

_*guidebook*__one_of_its_foldo.jpg)

_*guidebook*__one_of_its_foldo.jpg)