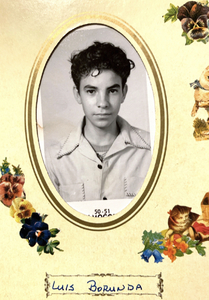

At a holiday dinner with my family in Los Ángeles, I peruse a collection of photographs of my abuelo from the months before he passed. As I examine his photos, I cannot help but notice the physical transformation he underwent—the discoloration of his skin and the phantasmic look in his eyes. My abuelo—Luis Gallegos Borunda—was a brilliant nuevomexicano[1] whose life was tragically cut short by an aggressive and bizarre cancer in 1994, at the relatively young age of fifty-eight, when I was still a child. He had been a community leader and the director of LA’s Head Start during the height of the Chicano movement. The eeriness of the images, the ways in which they act as mediations of his deteriorating health, prompt me as a film and media scholar to consider what other aspects of Luis’s death have also gone unconveyed. I recall that my abuelo was a child in 1945 in his hometown of Alamogordo, Nuevo México[2]—only 126 kilometers away from the world’s first atomic implosion at the Trinity Site—a frightening aspect of his life that is rarely discussed among my now largely California-based family. My abuelo’s second spouse—my step-abuela—then confirms that Trinity was indeed on my abuelo’s mind before his death. Her corroborations and my abuelo’s bodily condition in those images provide a material form for his absence for much of my life. As Karen Barad says, “hauntings are not immaterial” (2017, G107). Indeed, the invisible man, a common trope in atomic cinema, in the form of my abuelo does leave behind an atomic trace (Lippit 2005, 82, 102).

My abuelo’s community and surrounding ones in Nuevo México were especially vulnerable to the world’s first atomic implosion (an atomic explosion requires a plutonium implosion). Even though forty thousand people resided in the four counties around the Trinity Site—Lincoln, Otero, Socorro, and Sierra—they received no warning before the US government deployed the atomic bomb in the region on July 16, 1945, only weeks before the atomic attacks on Japan in August (M. Gómez 2017, 17). As I continue my investigations, I connect with community leader and activist Tina Cordova, the founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium (TBDC). The TBDC seeks to receive a formal apology for Nuevo México (as other states have gotten), health-care support, and reparations for the region’s downwind populations from the federal government. The Tularosa Basin Downwinders can currently accomplish these goals only if they are successful in their fight for the state’s overdue inclusion into the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which provides these benefits to those unjustly impacted by atomic weapons and mining in the United States. Downwind populations in many other states victimized by atomic bombs, such as Arizona, Nevada, and Utah, have received reparations and assistance through RECA (which was first passed in 1990). Downwind populations elsewhere impacted by the production of the world’s earliest atomic weapons in the state of Washington, for example, have also received some reparations via outside lawsuits (Brown 2013, 315).

In contrast, downwind populations in Nuevo México and Guam, places in the United States with considerable Indigenous communities and communities of color, are among those who continue their fight for reparations and equitable treatment from the US government. In response to these unjust disparities faced specifically by Nuevo México, in an interview with Vice, Cordova said these oftentimes impoverished communities were faced with a tripartite devastation: local people were “unknowing, unwilling, and uncompensated participants in the world’s largest lab test” (2016). The US government’s treatment of Nuevo México specifically also reflects its continuing role as the primary and “most important region in all of America’s nuclear weapons industry” (Wheeler 2021, 7).

The enormous national role of Nuevo México’s nuclear industry is embedded within specific legacies of colonialism and systemic environmental racism, legacies that differ from those of the rest of the US Southwest. Instead, the timeline for the colonization of Nuevo México in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries bears more resemblance to the US imperial projects in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines (Mitchell 2005, 18). Because this colonial history is recent, it is somewhat surprising that neither public nor academic discourse has commonly tracked the transition of Nuevo México from formal US colonialism into a nuclear colony. Today, 48 percent of Nuevo México’s population is Latinx (the highest percentage of any US state), and 10 percent of the population is Indigenous (the second highest percentage of any US state); these are the communities that have, thus far, been denied access to RECA.[3]

I began with the personal here because my abuelo’s body, the photos of his corporeal deterioration, regional environmental activism, and the bomb itself have tremendous relevance to contemporary media studies and to the growth of a field that might be termed critical mediation studies.[4] After all, at the intersection of questions of media, life, nonlife, and the impacts of nuclear weapons and their infrastructures on bodies and environments is the matter of mediation. As a scholar of environmental media, I am interested not just in these photos of my abuelo as forms of “traditional” media but also in how they demonstrate that media is oftentimes contiguous with bodies, technologies, and environments. Atomic weapons themselves turn every being and the environment itself into “war’s recording surface, its film” (Virilio 1984, 85), showing the ways in which, under atomic conditions, conventional differentiations between bodies, environments, and media give way to bodies and environments as media (Chang 2015). While there is a multiplicity of ways to think about terms like medium and media, from biology to philosophy to digital streaming devices, mediation as taken up by recent turns in our field challenges us to think past “old” or “new” media—past concrete objects such as the telegraph, the iPhone, or smart cars. Instead, media function on dynamic and multiple registers within which technology, people, biology, the social, and the political are entangled (Kember and Zylinska 2012, xiii).

The bomb itself at Trinity was not external to local communities, a technology or an event that occurred “out there.” Questions previously asked by scholars about how “the Bomb” seems to exceed language and traditional forms of mediation (Matheson 2019, 12) might be reframed if we also transgress traditional understandings of media as static objects. Instead of seeing the bomb as transcending traditional forms of mediation and as global, I use this broader understanding of mediation to reframe the bomb at Trinity as exceedingly multimodal, distinctly regional, and a critical node in wider matrices of power. As I have already suggested, mediation, as deployed in this essay, includes a broad radioactive media ecology—referring to bodies, environments, and the subsequent cinematic depictions of the nuclear infrastructures—emerging from coloniality and its toxic and radioactive reverberations. It also both sheds light on how media constitute and reconstitute the dominant discourses of the world’s first atomic attack in Nuevo México and centers the dispersed accounts of the radioactive and racialized “slow violence” (Nixon 2013) faced especially by communities of color in the state.

In this essay, I argue that this broader understanding of media assists in recognizing mediation both on multiple scales as imbricated in systems of coloniality and as an experimental praxis that can support efforts of environmental justice around Trinity. To that end, I develop “mediations of atomic coloniality.” Building on work by media scholars and Latinx/Latin American postcolonial studies, I see this as a multimodal critical media studies approach to studying the roles of a polyphony of media forms in the formation of dominant public discourses about Trinity and the subsequent challenges to these discourses. The modes within mediations of atomic coloniality include (1) a site visit to Trinity; (2) early documentaries produced about the atomic attack that developed Eurocentric spatializations of the region; and (3) local activist media that I conceptually develop as “downwind media.” However, before I develop each aspect of this tripartite approach, I will first further define mediations of atomic coloniality and then provide some relevant historical context on Trinity itself.

Mediations of Atomic Coloniality

Scholars including Valerie Kuletz (1998), Joseph Masco (2006), Jake Kosek (2006), Julie Boddy (2009), Traci Voyles (2015), Lucie Genay (2019), and Myrriah Gómez (2020) have traced the impacts of US colonialism and neocolonialism in Nuevo México in relation to the nuclear industry and its impacts on the region’s majority communities of color. However, no scholarship has yet to deeply consider the role of coloniality at Trinity. In Latin American/Latinx subaltern studies, coloniality refers to the endurance of Euro-US colonial structures and epistemologies, even after the end of formal colonization, via practices including the heterogeneous entanglements of capital, lasting racial hierarchies, and others. Sociologist Aníbal Quijano (2000) first articulated the concept, building on the important work of scholars such as Pablo González Casanovas and Silva Rivera Cusicanqui (2012, 103). Coloniality has been criticized by scholars for the way that it—as formulated by Walter Mignolo, specifically—has often circulated as another form of academic imperialism in the Global North and has promoted multiculturalism over decolonization (Rivera Cusicanqui 2012, 104). While such critiques are of deep importance, I focus less here on how coloniality has circulated and more on what it reveals when applied alongside a broadened understanding of “media” and “mediation” in early atomic history in Nuevo México. Thus, rather than use coloniality solely as a concept, I develop mediations of atomic coloniality as an experimental environmental justice praxis composed of discursive and material analyses that contributes an interdisciplinary but mediation-centric approach to histories around Trinity.

I see value in this multifaceted approach as one possible “media studies” response to historian Sean Malloy’s point that too little of racialized colonialism has made its way into the scholarship around histories of nuclear technologies (2021, 68). Likewise, scholars such as Gabrielle Hecht have persuasively argued that “nuclear ontologies” have specific histories, filled with racialized and colonialized geographies (2017, 642). I foreground these points as I deploy mediations of atomic coloniality as an inventive, multipronged approach deriving from Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska’s call for “creative mediation[s]” grounded in interdisciplinary “participation and invention” (2012, 200, 203). It is also inspired by Lisa Parks’s “signal territories” as an aesthetic and embodied approach to study broadcast infrastructures (2013). I too seek to deploy a wider repertoire to approach these earliest of nuclear infrastructures at Trinity, their public representations, and residues. By broadening what I mean by “media” here, I expand what discursive and media intersections are of concern to both those in the humanities working on atomic infrastructures and also, perhaps, those publics working toward environmental justice around Trinity.

In numerous ways, coloniality guides us to new insights around the regional nuclearity of Nuevo México (and its connections to Spanish, Mexican, and especially US settler colonialism in the region). After all, Nuevo México contained substantial numbers of Indigenous communities and the largest number of Mexican citizens that came under US jurisdiction following the Mexican-American War (L. Gómez 2020, 25). For decades both the region’s racial and linguistic compositions were central concerns for US lawmakers in their opposition to statehood for Nuevo México (Larson 2013). The first language for many was either Spanish (Montgomery 2002, 184) or an Indigenous language. Many Indigenous communities in the region were (and still are) multilingual and spoke (or speak) Spanish as a lingua franca (Lozano 2018, 3). Nuevomexicanos in the area, including my family members, learned English as a second language if they knew it at all. Even as late as 1961, the US Census Bureau claimed that Spanish was still “established on an equal footing” to English in the state (US Bureau of the Census 1963, X).

Prior to statehood, in 1902, US senator Albert J. Beveridge argued that the region itself was composed of “this mass of people, unlike us in race, language, and social customs…” (my emphasis), and it was commonly held that the region required more Anglo populations, cultural practices, and English speakers before statehood could be granted (Lozano 2018, 131). For more than a half century, lawmakers in the US government and US print media argued that mestizo “Mexicans and Indians were too wild and irresponsible” to be the predominant populace of a US state (L. Gómez 2008, 81). These attitudes did not suddenly dissipate with the arrival of statehood in 1912. Indeed, the region shifted from a colony that was described as rich with resources—only lacking the necessary white and English-speaking population and leaders for statehood—to an exotic tourist site for these populations and, eventually, one of the states central to the US atomic efforts (Andrés 2000, 243, 252; Lang 1976, 195).

It was within this nexus of coloniality, tourism, and racist escapism that scholars should frame the seemingly benign appreciation of J. Robert Oppenheimer (the head physicist at Los Alamos and “father” of the atomic bomb) for Nuevo México and his advocacy for the region to house what became the laboratories in Los Alamos. The same is true for the decision by the directors of the Manhattan Project to use the world’s first atomic bomb in the region and the reality that by the early 2000s, Nuevo México was the only state to support the entire “cradle-to-grave” nuclear economy (e.g., from mining to detonation to waste storage) (Masco 2006, 35). For these reasons, I write of an “atomic attack” to describe the atomic implosion at Trinity. “Atomic test” occludes Trinity’s relation to coloniality and the violence inherent in atomic weapons; by contrast, “atomic attack” more effectively explicates that there were clear victims as the result of this atomic violence, a reality that many experts in the US government foresaw, as I will unpack in the next section.

Coloniality is not just about the continuation of colonization, though; it also draws our attention to the absences and gaps that narratives of Eurocentric (here, atomic) modernity, rationality, and expertise produce (Mignolo 2005, xi, xii). Such gaps have been underscored by the efforts of locals in the TBDC through their use of grassroots media to preserve the oft-overlooked lived experiences of these communities. As Rahul Mukherjee (2016, 99) has argued, toxic infrastructures—such as radioactive infrastructures—and their “disruptions… [generate] new social arrangements,” new environmental publics, and new ways for communities to represent themselves. In the final sections of this essay, I delineate the ways in which the TBDC and their allies seek to delink themselves from the discourses common in outside atomic “expertise.” The communal practices of the TBDC point toward the emergence of a “downwind media”: forms of media and mediated practices about the histories of Trinity grounded in a critical unknowing of Eurocentric atomic epistemologies, geographies, and archival forms. Downwind media is also based in an ontological respect for local landscapes, languages, and memories—or what Indigenous, Genízaro, and Chicanx scholars from the region have engaged with as the concept of querencia (Arellano 1997; Fonseca-Chávez, Romero, and Herrera 2020).

Atomic Science as Colonial Science at Trinity and Geographies of Unknowing

Leaders within the military-industrial-scientific complex privy to the specifics of atomic development understood some of the dangers to which they were going to expose local communities when they detonated Gadget, the plutonium implosion device, at the Trinity Site. The fact that the weapon at Trinity was effectively identical to the Fat Man bomb that the military later used in Nagasaki further underscores this point (Ball 1986). Prior to the implosion, physicist Enrico Fermi even joked that the weapon might set fire to the air, but only over New Mexico (Miller 1986, 23).

The disregard held for the region by Fermi in this exchange was shared elsewhere; the army preemptively prepared four alternative statements based on the variety of the possible outcomes at Trinity—even potentially genocidal ones (Wellerstein 2021, 108). After Trinity, the army released what they thought was the appropriate option of these four: a false statement published in local newspapers that explained how the explosion was the result of the unintentional detonation of explosives and pyrotechnics (Szasz 1984, 84). To justify these deceptions, a memo—likely penned by General Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project— described Nuevo México as a “big place” with “few people living in it” (Wellerstein 2021, 108). This memo reveals how Nuevo México had to be reimagined for the events at Trinity to occur smoothly: from a place too full of “masses” of communities of color for statehood three decades earlier, to one now sufficiently unpopulated enough to perform this atomic attack. It was, of course, untrue that Nuevo México had “few people living in it.” In addition to the forty thousand people living in the four counties adjacent to Trinity, more than a half-million residents lived in the entire state at the time. Vulnerable communities likely approached one million people if we include neighboring cities like El Paso and Ciudad Juárez.

Some scientists working on the Manhattan Project did have concerns for the health of workers and locals and the habitability of nearby areas after the blast and raised the possibility of future lawsuits (Nolan 2020, 69, 274). In 1986 Louis Hempelmann, a doctor at Los Alamos, stated in an interview that scientists working at Trinity were concerned that “a few people were probably overexposed, but they couldn’t prove it and we couldn’t prove it. So we just assumed we got away with it” (Nolan 2020, 105). Even General Groves showed a degree of concern when he warned Governor John Dempsey that the governor might need to declare martial law in the state due to the material and social fallout that could occur from Trinity (Groves 1983, 269, 289). There were partial evacuation plans, which signaled that the government was aware that populations were nearby, should the worst occur, but these plans also conveniently avoided evacuating larger towns due to the complications involved (Genay 2019, 91, 92).[5]

After the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that followed Trinity, the US Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission relied extensively upon Japanese scientific data. Given the power that the US military had over Japan at the time, early atomic science amounted very much to a sort of “colonial science” (Lindee 1997, 17–20). Although Nuevo México was a very different encounter compared to Japan, Trinity nevertheless also produced colonial science as reflected in both the decisions leading up to the dropping of the atomic bomb and the collection, creation, and maintenance of often-troubling atomic scientific “facts” in the aftermath.

Following Trinity, there were numerous accounts of negative health impacts in the area, yet the US government did little in response. Locals reported bizarre effects from radiation on humans and animals and, even more disturbingly, local medical officials warned about a 57 percent increase in infant mortality between 1945 and 1947 (Tucker and Alvarez 2019). Yet the federal government did very little afterwards to monitor the impacts of the Trinity explosion on nearby communities. UCLA conducted classified annual reports from 1948 to 1955, but the fear of lawsuits again made the Atomic Energy Commission reluctant to even sanction these. The UCLA surveys concluded that dangers did exist from Trinity and that continued annual reporting was necessary—advice the commission ignored after 1955 (Szasz 1984, 134, 135). For the next thirty-two years, very few evaluations of regional public health were done. Only in 1987 did the US Department of Energy release an analysis of the radiological and meteorological data at Trinity.

Finally, in the 2000s, the US government recognized some of Trinity’s impacts on local communities. In 2010 the Centers for Disease Control reviewed the available documents and concluded that, while the data was extraordinarily incomplete since there were no government attempts to record local exposure to radiation through the consumption of food and water, “exposure rates in public areas from the world’s first nuclear explosion were measured at levels 10,000 times higher than currently allowed” (Centers for Disease Control 2010, ES-34). Two years later the US Department of Energy went as far as to say that the atomic implosion at Trinity “posed the most significant hazard of the entire Manhattan Project” (2012, 5).

Seventy-five years after the attack, in 2020, the National Cancer Institute released a study six years in the making that they have described as the most comprehensive study of Trinity (Linshi 2014). Led by Dr. Steven Simon, a former scientist at the Los Alamos lab, this study generally minimized the impacts of the blast and backtracked on some of the recent preceding governmental evaluations. One part of the study concluded that the “Doses received from Trinity by external irradiation were not large except in very limited areas immediately downwind of the detonation site” (Simon et al. 2020, 455). Yet it also acknowledged that estimating the numbers of impacted people was a process riddled with “great uncertainty” (National Cancer Institute 2020).

The inconclusive vacillations of these intermittent studies reinforce “geographies of unknowing” (Mukherjee 2020), where victims of radiation in the region and their families cannot receive the treatment or the reparations that they need. As I describe in the next section on my site visit to Trinity, such scenarios of unknowing and deference to outside experts also propagate imaginaries of nuclear expertise. Unknowing is a common condition suffered by victims of atomic technologies (Hecht 2012); indeed, a motto used by the TBDC is “unknowing, unwilling, and uncompensated.” My interest here is also to consider a form of critical unknowing, or unknowing as an action or praxis taken up by environmental publics and their media tools. In a later section, I explore how organizations such as the TBDC use media activism to unknow Eurocentric atomic knowledge and thus challenge these very geographies of unknowing.

Mediations of Atomic Coloniality I: Site Visit and Expertise at Trinity

Despite the harm caused by the atomic attacks during World War II, the Trinity Site and its media objects eagerly celebrate an atomic modernity and reinforce discourses around Eurocentric atomic expertise. Mignolo describes “the ‘unity’ of the colonial matrix of power” in which “the rhetoric of modernity and the logic of coloniality are its two sides: one constantly named and celebrated (progress, development, growth) and the other silenced or named as problems to be solved by the former (poverty, misery, inequities, injustices, corruption, commodification, and dispensability of human life)” (Mignolo 2011, xviii). In this section, I use an ethnographic account of my site visit to Trinity to analyze how the Trinity Site secures both sides of this logic by acting as what Nicole Starosielski terms a visual “buffer zone” (2015, 126). The site carefully curates a variety of media forms to mediate and celebrate the themes of scientific and economic progress via the arrival of new jobs as well as white scientists and their families to the region—and simultaneously buffers and silences local accounts of radioactive toxicities. The dangers resulting from the atomic are carefully contained and secured by the semiotic power of the discourses of control and oversight expressed by the site. Trinity, the nation, and the globe are the emphases put forward by the site’s management, while any sense of the local commons is absent.

As I approach Trinity, I realize that the admissions process will be extraordinarily time-consuming; visitors must wait in a line of automobiles that, by the time I arrive, spans approximately one mile. I wait in line for roughly thirty minutes, but later arrivals are delayed for even longer as we all must wait for soldiers to admit us into the site. The Trinity Site is on the White Sands Missile Range— still an active military base—and, thus, this national historic landmark is open only two days per year to the public. Before admission, guests must answer questions from armed soldiers about why they are visiting, whether they have weapons, and if they have cameras recording the entrance process. Put succinctly, the Trinity Site is likely one of the most heavily secured national historic landmarks in the country; but these “buffering” procedures are also forms of embodied knowledge-making at Trinity. These procedures reflect the discourses of security at the site; the securing of bodies flows into the epistemological and vice versa.

While I explore the grounds, I develop an understanding of how the site as a geophysical and historical space is mediated for the public by the various divisions of the federal and state governments involved with the site’s construction and current upkeep. To process the site, I pose as a tourist and take photographs on my DSLR, record notes, and make sketches of the design of the site. I note that the exhibit closest to the site’s entrance is an intimidating steel cylinder designated Jumbo; this looms over visitors upon their approach to the site. Weighing 214 tons, this enormous object is the unused container for the world’s first atomic bomb; it was never used because scientists eventually deemed this multimillion-dollar steel cylinder unnecessary to protect Gadget’s plutonium. The cylinder was instead left nearby during the blast. The sign for Jumbo proudly proclaims that while the atomic blast “destroyed the tower [from which the bomb was dropped, the nearby] Jumbo survived intact.” Thus, this enormous security device is the foremost item at the site’s entrance to highlight and celebrate the expertise demonstrated by even this ultimately unnecessary safety device.

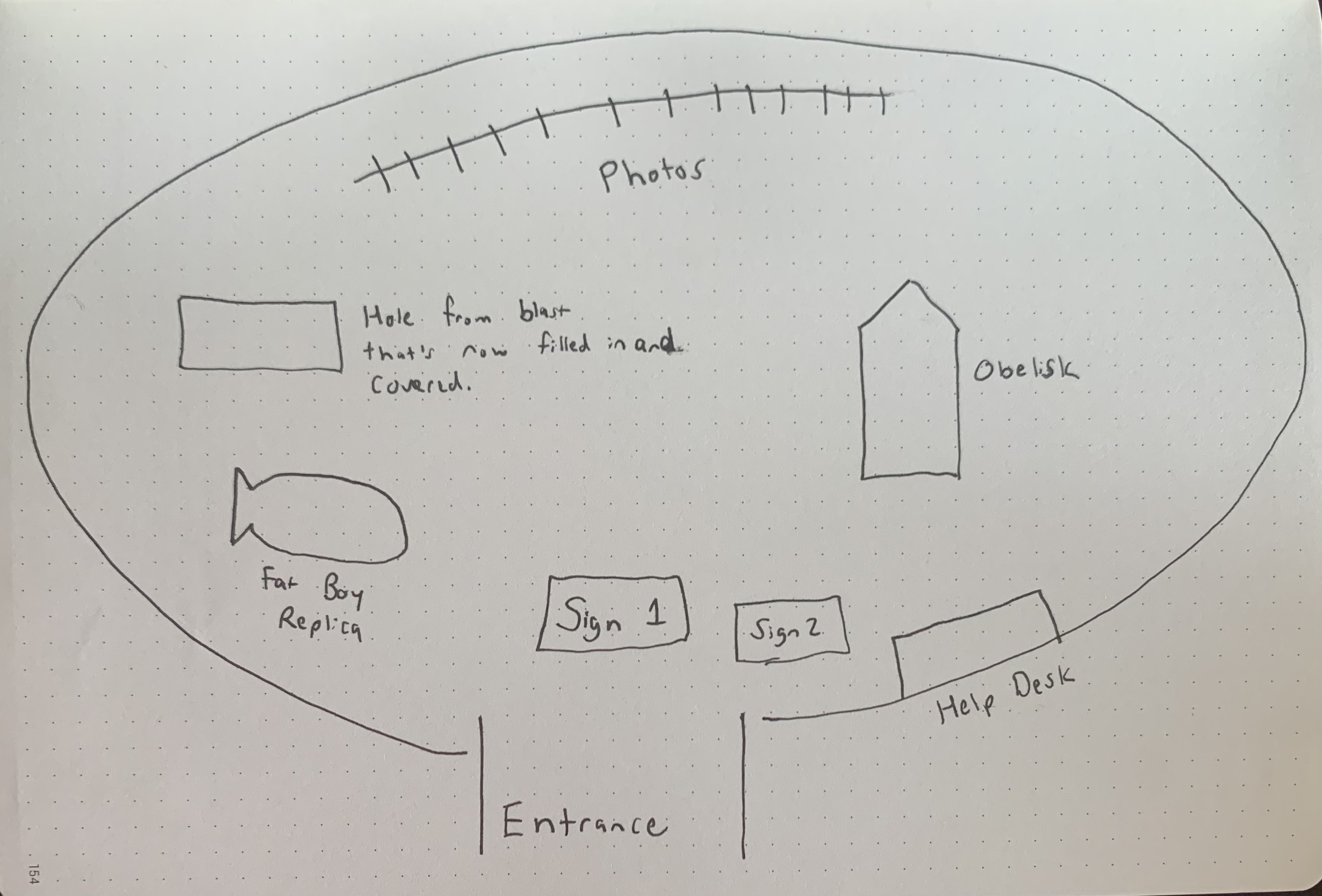

After several steps on the dirt pathway leading to the site, visitors note that the pathway and the blast site itself in the distance are surrounded by barbed wire fences, sorts of physical media with particular semiotic functions. The eerily corresponding fences at Los Alamos, about 315 kilometers away from Trinity, have been analyzed by scholars such as Myrriah Gómez and James Masco. Both see the fences of the Los Alamos National Laboratory as being physical and symbolic tools that function to separate Los Alamos as a space from its local Indigenous and nuevomexicano peoples, each with their local epistemologies of land and time (M. Gómez 2020, 174; Masco 2006, 106, 125). Additionally, the fences mask land theft that occurred under the guise of eminent domain—land thefts that, as Jake Kosek notes, allowed for the creation of Los Alamos while ignoring the territorial rights of the Indigenous Pueblos of San Ildefonso and Santa Clara as well as the Spanish and then Mexican Ramón Vigil land grant (2006, 250). Similar ideological moves toward both segmentation and securitization occur at the Trinity Site; as I sketch the site, I note the oval shape of the fenced zone that represents ground zero. This shape creates an outline strongly reminiscent of a mushroom cloud—but firm and with exact limits. I then enter this central zone, where an obelisk sits in the center to show exactly “where the world’s first nuclear device was exploded” (my emphasis).

Both the fence and the obelisk suggest that the events of the blast were restricted to the enclosed area but that the impacts belonged to the globe. The atomic as a concept and the attack as a material event become simultaneously more concentrated, even separate from the region itself, but also more global. The event occurred only here under the close watch of what Masco calls the United States’ “first nuclear scientific community” (2006, 75), and this landmark now provides equal cause for celebration for all in the nation and beyond. At the farthest portions of the fence in relation to the entrance, there are approximately twenty-five photos of scientists, military leaders, and moments deemed by the exhibit’s creators to be essential to the atomic implosion at the Trinity Site. Portraits of Captain William Parsons, Dr. Ken Bainbridge, and candid snapshots of other soldiers and scientists “in action” hang from the fence. Information signs near the images tell us that “Radiation levels in the fenced, ground zero area are very low,” while another series of photographs divides the enormous atomic mushroom cloud into milliseconds, emphasizing the brief duration of the blast. Such images and signage present an orderly vision of the event, limited in impact and duration. The images also confirm the popular historical accounts that Lucie Genay describes as largely a narrative about scientific “heroes” leading an “enterprise that ended the war and saved the free world from fascism” while “operating in the name of science and progress” (Genay 2019, 1, 3). The mediating objects at the site—the photographs and their signage, the monument, and the fence itself—all attempt to fortify the illusion of containment overseen by white experts; the explosion took place only here, and here is where it stopped. Concurrently and ironically, visitors are also warned by other signs (and soldiers) that the site is still radioactive, and removing trinitite (a radioactive rock created from sand that was converted into glass by the atomic blast) from the site is illegal. In such paradoxical moments, the attempts to secure the narratives of unquestioned safety are unable to fully exclude and visually buffer the importance of the body and land as media forms in the wider media ecology of Trinity.

The commitment to Trinity as a scientifically and epistemologically secure site and a global one runs deep and beyond the site itself. The absence of local testimonies about the bomb and its dangerous effects is consistent with the histories of the atomic labs and industries in Nuevo México. The laborers of color who worked and serviced the labs that created the bomb and subsequent nuclear weapons in Los Alamos have also been regularly neglected in public accounts of the bomb’s construction (Maciel and Gonzales-Berry 2000, 90; M. Gómez 2020, 162). The female domestic workers from these communities who worked for the families of (largely) white scientists have been even more overlooked (M. Gómez 2020, 169). One exception to these erasures is the University of New Mexico’s oral history project published in the 1990s, called “Impact Los Alamos: Traditional New Mexico in a High Tech World,” which gives the accounts of impacted Indigenous and nuevomexicano communities living near Los Alamos (Genay 2019, 5, 6). Such work challenged prior accounts of Eurocentric expertise that consistently overlooked the toxic impacts of technologies on communities of color, especially women of color (Nakamura 2014, 920). Unfortunately, such erasures continue at the Trinity Site today in favor of discourses of security, expertise, and the globality of the bomb.

Mediations of Atomic Coloniality II: Nuevo México On-screen in the Early Atomic Age

While the history of atomic cinema has been explored extensively (for instance, see Weart 1989; Evans 1998; Perrine 1998; and Shapiro 2002), to my knowledge nothing has been said about the role of Nuevo México—or its spatialization—in early atomic documentary films. Yet the control of space is central to both coloniality (Mignolo 2005, 49) and to documentaries, as argued by scholars, including Janet Walker, who underscore the importance of “creative geographies” of documentary space and mapping as an analytic (Walker 2018). This lack of scholarly attention to regional spatiality in early atomic films shot in Nuevo México may reflect the fact that, despite all of the time the atomic scientists and engineers spent in the region, the area functioned as little more than an empty land devoid of history and culture in earlier atomic films. It was simply a zone where the bomb just happened to have been detonated. Complicating this narrative, in this section I argue that two early atomic films that relied on documentary filmmaking not only delineated convenient expert atomic histories for mass public consumption but also reformulated epistemologies of regional space around Trinity.

With a run time of just under twenty minutes, the documentary short Atomic Power (dir. Jack Glenn, 1946)—part of the March of Time series produced by Time Inc.— summarizes the key moments in the creation of the atomic weapons by the Manhattan Project. The documentary pays special attention to the events before and after Trinity to demonstrate the ingenuity and efforts of nuclear scientists, as well as the benefits and personal risks that resulted from their work. Since the March of Time pieces were often seen by millions of filmgoers in theaters in the United States, this short documentary was one of the earliest forms of mass visual media produced to educate the US public about the bomb. The documentary even received a nomination for an Academy Award for best documentary short. The documentary features the narration of Westbrook Van Voorhis, the series’ host, to guide spectators through the happenings in the development of the atomic bomb on-screen. The film opens with various concerns about the bomb from members of the US public. Such anxieties are met directly in the documentary by the individuals who helped to create and engineer the bomb; producer Dick de Rochemont was eager for the film to feature the actual scientists who crafted the bomb before they passed away (Fielding 1978, 290, 291). Therefore, many of the key scientists and military officials reenact their real-world roles in the film.

Atomic experts such as Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard, Isidor Isaac Rabi, and Albert Einstein all have crucial roles in reenactments in brief scenes that serve to capture the chief contribution of each scientist in the weapon’s maturation. General Groves is featured prominently in several of the reenacted scenes, and his primary concern as a character in the short is that the plutonium is treated with care since “fifty million dollars” went into the research. But this aura of US expertise, which is of great concern to the documentary, required repetition and practice for the scientists and military officials to exude. Outtakes of the film housed at the National Archives show General Groves reading off conspicuously placed scripts so he could easily manage his dialogue.[6] There was no possibility of deviation from approved messaging. The illusion of atomic institutional superiority demands that Groves and others neither attempt to memorize nor improvise lines. Extemporaneous speaking itself becomes an impossibility in the documentary to sustain discourses of expertise and control.

While the specter of the dawn of the Cold War looms in the film, the film’s brief but important spatial and cartographic engagements with Trinity also provide formally absent local communities a spectral presence. Just as my abuelo’s photos opened certain lines of inquiry, so, too, these reenacted moments in the documentary make visible an absence. Bill Nichols claims that documentaries with reenactments surrender their “indexical bond to the original event. It draws its fantasmatic power from this very fact… The viewer experiences the uncanny sense of a repetition of what remains historically unique. A specter haunts the text” (2008, 74). In Atomic Power, if reenactments flutter between the multiple temporalities, this is, in part, to create very specific geographies. While describing the movement of atomic technologies necessary for Trinity, the documentary presents a map of the continental United States highlighting Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; and Los Alamos as sites crucial in these efforts. The documentary then describes these new atomic towns as “virtually isolated.” Shortly afterward, the documentary begins to focus specifically on Nuevo México as scientists are seen reenacting their preparations for the world’s first atomic implosion at Trinity. Prior to deploying the bomb, military officials and scientists sketch a map of the area around the Trinity Site, and they conspicuously label the map “Alamogordo,” but any depiction of my abuelo’s town itself and its approximately three thousand inhabitants is not included in this cartographic image. There is an intentional consolidation of space moving from the national map to this even more impoverished local map of Alamogordo—the details included are just the location of the bomb, the “base camp,” “control,” and the location of the photographer.

After the events of Trinity and the atomic attacks by the United States on Japan, the documentary warns about the dangers of future atomic attacks by showing an extremely sophisticated map of New York City, very much in contrast to those preceding simplistic maps that represented Nuevo México. While the previous map made it difficult to even ascertain that Alamogordo was, in fact, one of many populated towns near Trinity, in this map of New York we see New Jersey, the Hudson River, Manhattan, and the Bronx. This map is then followed by a graphic of New York City in flames as Van Voorhis simultaneously narrates that scientists must continue to educate the US public about how atomic weapons could strike anywhere—neglecting to say that the United States had already detonated these weapons both abroad and domestically near its own communities of color. Reenactment and mapping are used by Glenn and other creative powers behind the documentary to publicly explain and rationalize this initial usage of the bomb via a particular depiction of regional spaces. The film’s use of maps accords with its spatial ethos of exclusion. Yet the phantoms of nearby communities, including my family and the families of other Tularosa Basin Downwinders, cannot be totally erased. Local communities operate as a specter in space, not embodied in the documentary, but still lingering.

Documentary footage was also important in director Jerry Hopper’s narrative feature The Atomic City (1952), which was nominated for an Academy Award for best writing. The film fictionalizes the threats that atomic scientists and their families faced from foreign spies seeking to steal sensitive atomic secrets. Its first image is a title card that spatially orients us as it reads “Alamogordo, New Mexico. July 16, 1945. 5:30 AM.” Due to the lack of a fade, the title card and the name of the town on-screen seem to explode in a flash as spectators witness footage of the first atomic bomb at Trinity. We are then suddenly, inconspicuously spatially dislocated from Trinity and move northward as we witness scientists working on-screen in what the narrator terms a “remote section of New Mexico.” The narrator explains that the atomic age originated in the labs of Los Alamos, also known as “the Atomic City”—the central setting for the film. However, of equal importance to the laboratory interiors are the exterior physical infrastructures: barbed wire fencing and signage similar to those I found at the Trinity Site. According to the narrator, scientists and military personnel behind the fences “worked and struggled for more than four years to the end that the horror of World War II be quickly concluded,” which led to the successful creation of the bomb. While the sequences acknowledge the horrors in Japan, the film is quick to add that these same scientists and techniques that caused so much destruction are also the ones working to keep us safe now; the narrator claims “isotopes and other atomic techniques are saving lives all over the world.” We must be thankful, the narrator avers, to the brave scientists for doing such “unbelievably dangerous work” to both protect and advance US and global interests. Only the transformations brought about by the atomic age—and the necessary security and secrecy that Los Alamos provides—can “at last free man” around the globe. Such depictions of security and protection in service of international progress are, unfortunately, ironic given the harmful legacies of radiation from the laboratories on local Indigenous and nuevomexicano communities that have come to light over the past several decades (Kosek 2006; Masco 2006). Nevertheless, the film’s introduction blends together the spaces and events at Trinity with the daily protocols at Los Alamos and leads to associations of security and unquestioned expertise with both locations.

Mediations of Atomic Coloniality III: The Emergence of Downwind Media

The families that comprise the TBDC are fighting today for recognition and reparations for slow nuclear violence, and for a different historiography and geography to be mediated about Trinity. The recent conclusions by the National Cancer Institute about the general lack of a threat that Trinity posed to local communities—atomic epistemologies that reproduce the status quo—are challenged by the familial and community histories of the TBDC’s members. Congress did extend RECA’s coverage for an additional two years in July of 2022 but downwinders of Trinity in the region remain uncovered by this extension. RECA provides a state-based solution in the form of reparations and health care for victims in the region. While recent scholarship by scholars like David Pellow on critical environmental justice powerfully calls for solutions beyond the state (2017, 22), such solutions are also extraordinarily difficult to implement in situations where temporal registers and dangerous conditions created by the state itself necessitate immediate medical care for often already impoverished communities.

In these two last sections, I ask how the TBDC members are using local media in their practices of critical unknowing and their creation of atomic epistemologies that move beyond those currently propagated by the state. To think about the role of local media activism, I rely upon an interview that I conducted with Tina Cordova in the summer of 2019, given her role as the founder and key organizer of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders.

The TBDC highlights that people unknowingly worked with, ate, and drank—and children likely played with—contaminated matter after the atomic attack at Trinity (M. Gómez 2017, 66). The radioactive mediations that occurred through the bodies of living beings could have occurred through external exposure, inhaling, or ingesting contaminated foods and liquids. This could have led to immediate health threats as well as long-term impacts, in an example of what Rob Nixon terms “slow violence” (Nixon 2013, 7). In an age that focuses far too much on the spectacle and its physical origin, Nixon’s concept of “slow violence” instead points to how environmental degradation that occurs at the hands of human actors can slowly accumulate across lengthy timelines and across spaces in ways just as deadly. But the radioactive aftermath of this first atomic attack, an attack in which humans and human infrastructures were generally not immediately destroyed, muddles the bounds between slow violence and spectacle. Trinity contained aspects of both. The state, as shown by my Trinity Site visit and early documentaries, has often grounded its epistemologies in a brief spectacle that had no or few immediate causalities; by contrast, as I outline here, downwind media reformulates atomic epistemes in local knowledges of slow violence.

Since the consortium’s founding in 2005, the TBDC has collected testimonies and health surveys from approximately eight hundred locals who suffered or died from cancer in the region, and the group has published some of these familial testimonials on its website (interview, Cordova, July 12, 2019, Albuquerque). According to Cordova’s experiences and the group’s data collection, Indigenous and Latinx nuevomexicano communities were especially vulnerable because of their large numbers and intimate ties to their environments. In my abuelo’s hometown of Alamogordo, families built adobe houses with nearby clay. Both Indigenous communities and nuevomexicanos largely harvested and ate maize and other vegetables and fruits that they grew themselves. Today, members of these communities work together in groups like the TBDC, accompanied by activism from Indigenous groups like Honor Our Pueblo Existence and Indigenous/Latinx coalition groups like Las Mujeres Hablan (Lee 2014).

The cultural dynamics of these communities and their community-led research continue to be overlooked. The 2020 report of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) downplayed the importance of water infrastructures such as acequias (historic irrigation canals still in use by Indigenous and nuevomexicano communities) and cisterns. According to the NCI, the acequias were not worth quantifying because their surface area was too small to be impacted by radioactive fallout (Bouville et al. 2020, 415). Cordova sees the acequias differently: as a community-specific infrastructure that is central to local concerns. She recalls that her “community in Tularosa has the largest acequia system in the state. There are 14 miles of ditches… families that moved northwards from Mexico settled in the area and knew that they had found an oasis, that they could live there, and have water year-round… every home has a ditch with running water. The whole reason for the settlement of Tularosa, the whole reason for our Mexican ancestors’ connection to that land, in particular, was because of the water…” (interview, Cordova, July 12, 2019, Albuquerque).

While these ills cannot be undone, nor can we immediately change the current media at the Trinity Site and past popular documentaries about the atomic attack, we can look to the same communities that were most impacted to provide steps forward. Kember and Zylinska ask whether “the role of media is not only to perpetuate ideas but to bring about realities…” (Kember and Zylinska 2012, 37). In this final component of the mediations of atomic coloniality approach, I consider how the TBDC and its partners are reformulating and acknowledging their realities through media activism. Does mediation have the capacity, in Derridean terms, to be both the “remedy and poison” in Nuevo México? (Derrida 1983, 70). I develop downwind media as it relates to a variety of media forms from the Tularosa Downwinders that range from the group’s annual vigils to cinematic and digital media forms.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the terms downwind, down-wind, or down the wind mean to move in the direction of the wind, but also to move toward oblivion and decay—an appropriate description of the health consequences of atomic radiation. Additionally, “Downwinders” signifies the Tularosa Basin Downwinders themselves as a public. Might the emergence of a downwind media—media in both its contemporary usage signifying a technique of spreading information and its traditional usage as a medium or environment—suggest an acknowledgment of this dual usage: as something that can both cause and perpetuate environmental and bodily harm and as a form of media activism to critically unknow the centralizing, universalizing, and damaging erasures that preceded them? Something that can move us solely from accounts of atomic experts and atomic expertise at Trinity to that of communal forms of knowledge? Although “the whole world is downwind” (Barad 2017, G106), universalizing exposure in this way often overlooks how only certain communities are repeatedly forced to prove “downwinderness.” Downwind media acknowledges the various local temporalities and sources for inquiries into Trinity: my abuelo is a potential center—a person and place where inquiry into the memory of this event can begin again; the families of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders are centers; their neighboring ecosystems in southern Nuevo México are centers. Downwind media follows these asynchronous and regional translocational epistemological gesticulations, moving us away from Euro-American fantasies of the simultaneously global, expert, and constrained mediations of the atomic.

I first encounter downwind media when Tularosa Basin Downwinders participate in an annual vigil, which I attend in the summer of 2019. On a baseball field in Tularosa, at the vigil the finite bodily mediations of the repertoire are central: various community members name those approximately eight hundred local individuals (including my abuelo) over the microphone. In the adjacent field, hundreds of bright luminarias represent those lost to cancer in the community during this period of history. Each name said aloud precedes a single hit on a gong and two beats by a drummer. Three other musicians perform with singing bowls throughout the “performance protest” (I use this term as Diana Taylor deploys it: a cultural practice that “transmits traumatic memory” [Taylor 2003, 165]).

From their positions outside the elementary school’s baseball field, the approximately two hundred spectators in attendance listen and capture photos and videos on their cell phones, adding to the layers of mediation. Using drums, candles, and their voices to name the deceased, the Downwinders remember those they have lost and express their shared community trauma. Their performance protest approaches both locals and outsiders with mediated epistemes via bodies as a media, albeit in different and less violent ways than during the atomic attack. The vigil reminds us, too, of how practice and knowledge are embodied in the culturally “ephemeral”— “performances, gestures, orality, movement, dance, [and] singing” (Taylor 2003, 19, 20). In other words, knowledge is not found just in archival texts but also in bodily and artistic practices with finite temporalities, including this annual vigil.

TV and film also have the potential to shape downwind media. For instance, Cordova had high hopes that the recent television show Manhattan, which deals with the inner workings of the Manhattan Project, might portray local communities after she had promising conversations with influential actors on the show. “They want to tell your story [they said]… [but], then they [the WGN channel] cancelled the show” before the third season could begin, recounted Cordova (interview, Cordova, July 12, 2019, Albuquerque). By contrast, Myrriah Gómez has written about the way in which that same show, in preceding seasons, had little interest in understanding the ways in which Indigenous and nuevomexicano communities in Nuevo México were culturally connected with the land (2020, 174). This situation reveals the difficulty of relying on outside forces to depict local community dynamics and dilemmas that have been ignored elsewhere.

Cordova is more hopeful that a new documentary entitled Downwind, directed by Lois Lipman, who is based in Santa Fe, will provide an overdue public platform for these issues. Lipman has sworn to complete this project, which has been in production for years now. Cordova shares, “I really believe the documentary will be a huge success one day, an enlightenment… the documentary will provide perfect timing and assist our movement in a big way” (interview, Cordova, July 12, 2019, Albuquerque). In other words, if these communities can voice and embody themselves in this documentary, they may have another important means to able to center their environmental experiences. Lipman states that her career as a documentarian is based on “curiosity, research, and respect… honoring and respecting the people that have given me permission to honestly and truthfully reflect their stories. In New Mexico, there are such deep traditions, so I just seek to allow the camera to capture what’s happening in an honest and respectful way” (phone interview, Lipman, October 17, 2019).

Downwind Media and Locating Querencia

Downwind media describes practices of mediation (such as the vigil and the developing Downwind documentary) that decenter, unwill, and unknow preexisting national narratives about the atomic bomb. Another example is the emerging online testimonial archive that the Tularosa Downwinders are forming (in which I have been privileged enough to participate) about the vulnerability of water infrastructures like open cisterns to radiation during the Trinity attack. Downwind media permits a multiplicity of truths to also emerge from the regional accounts of survivors at Trinity, instead of just from those deemed experts who operate within systems that have historically caused harm to these communities.

Central to downwind media is the Indigenous and Chicanx concept of querencia, a sense of love for place and home (Fonseca-Chávez, Romero, and Herrera 2020). Juan Estevan Arellano fist presented this concept to understand the symbiotic relationship between nuevomexicanos and the land—the way in which their very cultural memory is entwined with the soil from Ciudad Juárez, in Mexico, to the San Luis Valley, in Colorado (the limits of nuevomexicano populations prior to the US assertion of power in the region) (Arellano 1997, 31). However, Arellano’s original development of querencia glosses over the Spanish Empire’s colonization and the colonial understanding of space that delineated these very limits for nuevomexicanos or Chicanx people in the region. Pueblo activists and scholars remind us that there are preceding practices of resistance to colonization and senses of home found in spiritual words like “amuu haatsi,” meaning “beloved land,” in Acoma Pueblo in Nuevo México (Chino, n.d., 201).

The intercultural ontology of querencia speaks to the Aymara metaphor of ch’ixi; Cusicanqui deploys this metaphor to signal the “included third”—that is, the “motley” and the ways in which cultural differences between Indigenous and mixed outside communities can be both antagonistic and complementary in the formation of a radical, transformed, and sustainable modernity. Ch’ixi acknowledges “a double and contentious ancestry” for the mestizx and the “colonization of [their] imaginar[ies]” but also the possibility of wider liberation following dialogical forms between communities that construct knowledges that pursue coexistence between peoples and their environments (Rivera Cusicanqui 2012, 105, 106). In this way, downwind media also calls for a radical reimagining of the geography of the land itself, to do away with the geographies of those who have control over the nuclear infrastructures and its histories—an end to the geographies of atomic islands (DeLoughrey 2012), of Los Alamos as a “floating island” that is imagined to not be “part of the bioregion,” and of Trinity as a place that is simultaneously global and outside lived time, space, and local life (Arellano 1997, 32). Downwind media are those mediations that work to return these radioactive sites to the land itself.

The nuclear industry was and is perceived as a regional bringer of prosperity in Nuevo México, a place that has been commonly depicted as belonging to the exotic and rural past (Genay 2019, 100). When it comes to the early atomic age, we might consider Mignolo’s words that “the logic of coloniality, that moves the world” has for too long been “disguised with the rhetoric of modernity, of salvation and progress” (2011, xvi). Even today, the modern economy of the state is in many ways driven by nuclear laboratories (Genay 2019, 230). “Development agendas prominent after World War II positioned modern technology as a solution to all manner of social and economic problems…,” says Cristina Venegas (2010, 9), and these agendas of “development” were implemented by the US government both abroad and domestically; the atomic infrastructure in Nuevo México is one important example of these efforts. The sort of linear understanding of history and progress championed by agendas of atomic development are also what downwind media may have the capacity to challenge. Querencia, aided by the ch’ixi (which acknowledges history as moving in cycles and spirals [Rivera Cusicanqui 2012, 96]), might also be deployed to highlight the intersections between temporalities and their mediations rather than clear divisions between past, present, and future and media objects and processes.

Conclusion: Mediation as a Praxis of Environmental Justice

Nuclear power and, to a lesser extent, nuclear weapons testing still have surprisingly broad support from many governments. But their promises of progress are complicated by the perils that the Tularosa Basin Downwinders continue to face and the dangers that communities of color endure under nation-states that discriminate against them on a variety of issues, including those of environmental justice. Might downwind media and its critical unknowing spread through society, just as atomic radiation from Trinity did all those years ago, but help bring insight—or even justice—instead of poison to the issues of the atomic? Only time will tell.

In this essay, I have developed mediations of atomic coloniality as an investigative media studies approach to Trinity, an injustice that for seventy-six years has seemingly moved “beyond an oversight” to “part of a longstanding cover-up…” (Wheeler 2021, 7). This approach has centered the ignored coloniality of the atomic in Nuevo México and a broad radioactive media ecology through a site visit by the author to the Trinity Site National Historic Landmark, early atomic documentary films and their spatialization of Nuevo México, and the emergence of what I term downwind media as taken up by local community activists in the TBDC. As an experimental praxis formulated, in part, to aid movements of environmental justice around both Trinity and the wider atomic Southwest, this approach uses discursive and material analyses to provide insights into the role of media in knowledge formation. I have deployed a broader understanding of mediation to consider the bomb at Trinity as exceedingly multimodal, distinctly regional, and a critical node in wider matrices of power and colonial legacies. But mediations of atomic coloniality was designed to be specific to Trinity, and my approach in this essay has been eclectic and is not definitive. In public spaces and critical media studies, we need to continue to articulate alternative histories of long-standing environmental injustices that have been overlooked. The more ways in which environmental injustices can be sensed, understood, and articulated, the more chance there is for publics to intercept epistemes that have centered expertise at the expense of local communities. My hope here is to encourage scholars to develop “creative mediations” as praxes in their efforts to do just that, to support environmental justice and build partnerships with community leaders and activists in presenting regional histories and injustices that might otherwise be missed downwind.

Acknowledgments

I offer profound thanks to Tina Cordova for her essential community leadership and support for this research. I also thank the graduate students in the UC Santa Barbara “Re-Centering Energy Justice” Research Group. Mona Damluji and Jéssica Coyotecatl Contreras have been the fearless leaders of this collective that has fostered important discussions and collaboration amongst the authors of this stream. I am also especially grateful to the editors of this stream–Javiera Barandiarán, Mona Damluji, Stephan Miescher, David Pellow, and Janet Walker–for their crucial feedback at various stages in this paper’s development. I also thank my MA committee of Cristina Venegas, Bhaskar Sarkar, and Janet Walker for their thoughtful commentary on earlier versions of this paper for my MA exam. Trinankur Banerjee, Peter Bloom, James Brooks, Alenda Chang, Isidro González, Jennifer Holt, Melody Jue, Lisa Parks, Mary Michael, Patrick McCray, Greg Siegel, Assatu Wisseh, and my peer reviewers also offered important support and feedback on many of the ideas here. I thank my family–especially my tío Adolfo, tío Pedro, and dear tía Florencia–for their openness to my questions, for their love, and for su forma de ser. This essay is for my abuelo, his siblings, and Victoria Dastres Cárdenas.

I use the geographical designation of nuevomexicano (while recognizing the political and ethnic genealogy of the term; see Meléndez 1997) to describe the historically Spanish-speaking Latinx or Chicanx communities in Nuevo México. The members of such communities selectively use converging and diverging ethnic labels such as Chicanx/Chicanas/Chicanos, hispanos, Hispanics, hispanoamericanos, indio hispanos, Latinx/Latina/Latino, la raza, manitos, mestizos, Mexican-Americans, mexicanos, nativos, nosotros, nuestra gente, neomejicanos, and Spanish Americans (Nieto-Phillips 2004, 4). It should be noted that this footnote has been the subject of many important books and articles in Chicanx Studies that I do not have the space to discuss here. For starting points on these terms’ social and political histories, see Nieto-Phillips 2004 or Meléndez 1997. “Feminist Insider Dilemmas: Constructing Ethnic Identity with ‘Chicana’ Informants” by Patricia Zavella is another classic article on this subject.

Use of “New Mexico” (an English translation of the Spanish “Nuevo México”) likely became widespread in the region after it became more connected with the rest of the United States with the construction of the national highway system after World War II. I readily acknowledge the colonial and violent history of the Spanish language (like English) in the region. But to center the local testimonies, accounts, and languages of the survivor communities, I defer to the Spanish term Nuevo México for the region—a term used by substantial numbers of Spanish-speaking locals during the era of the Trinity attack.

Included in RECA are uranium miners (not downwinders) who were impacted before 1971 in Nuevo México. However, impacted mining communities complain that this 1971 cutoff date is arbitrary and unfairly exclusionary. See https://www.abqjournal.com/2409305/dont-abandon-our-uranium-workers-in-nm-ex-the-radiation-exposure-compensation-act-reca-will-expire-on-july-11-2022.html.

I thank Media+Environment editor Janet Walker for coining this important term during a conversation about this essay.

Groves also made troubling and factually incorrect claims about local populations in his autobiography Now It Can Be Told. He proudly proclaimed that he was glad to avoid paperwork and legal troubles from the Bureau of Indian Affairs since the area near Alamogordo had “no Indian population at all” (Groves 1983, 269, 289); however, the Mescalero Apache Reservation lies just fifty kilometers north.

I thank Regina Longo and Steve Greene for providing me with access to these fascinating outtakes from the film conserved by the National Archives; These outtakes have now been digitized and can be accessed at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/149270488. The outtakes belong to the “March of Time” Collection, 1934 – 1951, and the Outtakes from ‘March Of Time’ Newsreels, 1934 – 1951 Series. The National Archives Identifier is 149270488.

_versus_a_map_of_new_york_city_(right)_in_the_*march_of_t.png)

_versus_a_map_of_new_york_city_(right)_in_the_*march_of_t.png)