There’s a slow poison out there that’s severely damaging our children and threatening to tear apart our culture. The ironic part is, it’s a “health food,” one of our most popular. […] The dangerous food I am speaking of is soy.

—Jim Rutz, Soy Is Making Kids Gay

And the soybean—well, it might be fit for animals and Orientals, but certainly not for Americans.

—quoted in Warren Belasco, Appetite for Change: How the Counterculture Took on the Food Industry

Soy is now an essential product of North American foodways. Materially, the plant is central to complex systems of industrial agriculture hinged upon commodity crops such as soy, corn, wheat, cattle, and rice. Soy forms a major part of the United States’ large-scale domestic production and exportation of foodstuff, making up some 90 percent of total domestic oilseed production and nearly 40 percent of the world’s soybean supply (USDA 2022). The United States is the globe’s second-largest producer of soy, and US crops reflect one-third of the demand for soy as livestock feed (Ritchie and Roser 2021). Biomedically, the legume proves to be “the most important dietary source of phytoestrogens in humans” (USDA 2010; see also Goldsmith 2008; Cederroth, Zimmermann, and Nef 2012, 193).

Given its increased ubiquity in industrial agriculture, health claims and fears abound about this humble legume. Worry over soy persists in a growing public ecomedia archive, ranging from Good Housekeeping, men’s health and fitness magazines, culinary blogs, sexual health websites, soy-specific product marketing, and even FDA health claims. From fears of male breast enlargement and worry over a generalized “feminization” by way of estrogen overdose, to proclaimed chemical castration, the questions and so-called “queering” effects swirling around soy are numerous. Such anxieties move beyond generalized inquiries about where on the body food affects us, as is the case with renewed debates over soy’s potential cardiovascular benefits or cholesterol-reducing capacities (Dennet 2018; FDA 2017). I want to suggest that it is the specific combination of biomedical complexity—the science is not, after all, clear cut and indeed makes its own specific presumptions in some instances—and gendered ecomedia representations that serves to propel a heightened ecopanic about soy phytoestrogen consumption. The ecopanic outlined in this article is co-constituted by way of the entanglements across and between popular media and biomedical data.

In an article for Scientific American, health commentator Lindsey Konkel asks, “Could Eating Too Much Soy Be Bad for You?” Reflecting on increased soy consumption in American foodways, Konkel (2009) notes, “Soy is ubiquitous in the American diet. Over a quarter of all infant formula sold is made with it, and the [USDA] promotes it in foods [including school lunch programs] to reduce the risk of heart disease.” Yet Konkel cites numerous animal studies concerned with the estrogen consumed in soy as potentially disruptive to reproductive, fetus, and thyroid development due to its “estrogenic qualities found in isoflavones” (Konkel 2009). In 2008 Columbia University’s health advice column Go Ask Alice—the nation’s oldest web-based health information site run by medical professionals—featured a soy inquiry, in which a student asks warily about soy’s ability to affect “masculine traits,” resulting in “more feminine” men (Go Ask Alice 2018). The cultural concern in the health advice column as well as in Konkel’s article—and exhibited in the opening epigraphs—is increasing. Common arguments about soy consumption—even the more extreme and far-fetched examples I will turn to momentarily—are far from reflective of mere conservative agendas. Rather, they reveal a collision between confusing nutritional information and a food moral panic about soy observable across left-wing and right-wing American food politics. We can observe these themes shifting over time from the 1960s—as Warren Belasco’s (2007) historical tracing of America’s racialized dietary resistance toward vegetarianism satirically points out—to the present moment. Contemporarily, these ideas manifest through presumptions about fixed “natural” bodies colliding with a neoliberal healthism that assumes individual health responsibility through “right” gastronomic consumerism. As feminist scholar Celia Roberts (2007, 164) argues, “Claims about endocrine-disrupting chemicals require sustained attention: the changes they are said to stimulate raise significant health and environmental concerns. However, [it] is also important to analyze the language used to describe sex hormones and their impact on bodies, behaviors and sexual difference.” I take Roberts’s call seriously in framing my analysis of gendered and racialized narratives about soy and the combined biomedical and ecomedia sources that propel these soy-specific fears.

Interdisciplinary ecomedia studies, gender studies, and food science and technology studies research provides an interwoven analysis of the scientific data, social narratives, and cultural anxieties interrogating soy through a gendered lens. I argue that the cultural narratives reflect a socially constructed sense of danger about soy that may draw from critical nutritional research of the legume, but that also center heteronormative and transphobic understandings of food as a hormonal, reproductive toxin working against “normal bodies.” Such panic is propelled, in part, through a rich and complex archive of ecomedia as well as by biomedical data that sometimes reflects rigid gender framings. This research reflects an interdisciplinary braiding of media analysis with insights from the fields of food, gender, and science studies, revealing ways in which panic about soy comes out of a historical moment of increased popular science communication, increased consumer fears concerning agricultural processing and toxic exposure, a grappling with the moral weight frequently attributed to food, and increased consumer concern over the hormonal influences of food—all of which collide in a moment of intensified US political debate over gender fluidity. For instance, just as increases in the number of gender-neutral bathrooms and strengthened policy-building in schools grapple with needs of trans youth across the United States and internationally, so, too, might we observe resistance to gender fluidity through increased queer-as-contagion or queer-as-toxin narratives.

Although conspiracy radio, popular magazines, and men’s health publications do not tend to be analyzed within the traditional parameters of ecomedia, I am suggesting that these are critical sources of pop-cultural diffusion and interpretation of environmental anxieties surrounding soy phytoestrogens. As scholar Salma Monani (2019) suggests, studies in ecomedia serve as “interrogation of the entanglements of nature and culture that mark our everyday use of media,” often permitting us to “see environment” in new ways. As I show through examples of soy in popular culture, including the above epigraphs, health fears and reproductive-centric moral panic are predicated on the collision of ethnocentric dietary concerns grounded in a generalized science-fictional fear of the ultimate terminator seed—that is, displacement or dismantling of patriarchal privilege by way of chemical castration. Moreover, such articulations remain at odds with years of nutritional data concerning soy consumption and its numerous health benefits, including for heart disease, menopause, and even cancer. The scientific data is likewise not without its own gendered and racialized assumptions at times, not solely regarding soy’s effects on men, but in its framings of soy as a static and generalized nutritional exposure in all Asians, rather than a context-specific, product-specific food ingested by diverse bodies in geographically and culinarily specific places, or altered by distinct industrialized processes that render it differently metabolized in the body (see, for example, Patisaul and Jefferson 2010; Chavarro et al. 2008; Cederroth et al. 2010; Lehraiki et al. 2011).[1] This article pursues intertwined analysis of the biomedical research and ecomedia popular culture to uniquely trace an ethnography of soy panic. It is only through such intertwined analysis across scientific texts and environmental media that the complex, trickle-down diffusion of popular science phytoestrogen anxieties may be revealed (see also Ahmad Khan 2020).

The popular environmental health focus on soy ingestion “aid[s] in the communication of urgent environmental issues” (Chang and Ivakhiv 2020). This focus also diffuses important questions about soy raised in biomedical studies of plant phytoestrogens through more accessible media channels. It likewise tends to underscore only the most titillating and panic-inducing points. As Alexa Weik von Mossner (2012) highlights, popular media has the ability to extend the reach of environmental and climate science information to enact social change. Similarly, popular media may also result in gaining a broader public reach of information on soy and human health, even if it is scientifically only partially accurate (at best). I propose a broader ontology of the soybean itself as it affects, or is presumed to affect, the human body, most especially as a supposed disruption to the heteronormative, cisgender male body.

Theory and Method

I focus my attention on contemporary examples of gendered soy fear and biomedical research available since 2007; these include culturally explosive examples of far-fetched, right-wing fearmongering about soy’s supposed effects on heterosexual men, as well as seemingly benign, yet equally gendered, worry over available nutritional information on soy ingestion. Though soy’s specific health benefits and impacts have intrigued scholars since the 1960s, I will focus especially here on the increased gendered fear of soy and “gender bending” over the last twelve to fifteen years (Raloff 1994; Barrett 2006; see also Roth 2018 on the rise of soy markets). Much like the language of food scares and moral panics, narratives about soy consumption as a queer(ing) toxin presume a pure, or “naturalized,” body. Such ideas emphasize reproductive-specific fear of environmental toxicity, in contrast to a broad-based equitable concern for the health of all life forms and informed consent in food. In this case, it is especially a “natural” state of masculinity that is proclaimed as tainted by way of soy phytoestrogen ingestion. As food scholar Charlotte Biltekoff (2013, 7) argues, “Nutrition is not only an empirical set of rules, but also a system of moral measures, and its presumably neutral quantitative strategies are themselves political and ideological.” Soy narratives, from the popular to the scientific, underscore the complex ways in which nutritional data is socially constructed knowledge and, at times, can be incredibly confusing to consumers.

Scholar Mei Mei Evans has argued that we are regularly confronted with media representations of “[heterosexual white men] doing battle against Nature in order to achieve 'real man’hood”—a theme that resurfaces in popular discourses about soy phytoestrogens (2002, 183). Through discourse and critical material analysis of popular culture manifestations of angst over the “queer” effects of soybeans, I argue for other critical environmental imaginings in line with work in queer and feminist political ecologies. This framing helps to “build sustainable livelihoods and just movements that refuse violence and ecological devastation without also refusing the polluted, the abject, the hybrid seed infiltrated with GMO genes, and the exposed bodies that we must learn not only to live with but to love” (Harcourt and Nelson 2015, 14). I suggest that soy panic extends the fickle nature of toxics discourse writ large as global producers and consumers navigate products and practices that may have effects that are context specific, and that may even be toxic or fertility affecting, yet simultaneously pleasurable, sought after, and desirable. Thus, I argue for other critical environmental imaginings in line with work in queer and feminist political ecologies,[2] and I explore why this fear discourse is a barrier to imagining more inclusive environmental possibilities that envision the body less as binarily im/pure, un/natural, and more as an ever-shifting active ecology.

Food-Induced Panic: The Incredible Shrinking Penis

Booth: [You’re] not gonna see me paying $4 for [an organic] tomato.

Bones: You know, a researcher at the University of Florida proved that alligators who swim in pesticide-contaminated waters have smaller genitalia than their clean-water counterparts.

Booth: No way?

Bones: Way.

—from Bones, “The Secret in the Soil”

An article in GQ magazine inquires, “How did soy get so scary? Soy was the OG health food king” (Zaleski 2020). Truer words were never spoken, and as Warren Belasco has pointed out, the soybean was once “icon of the countercuisine” (2007, 189). Concerns about environmental exposure to exogenous hormones and chemicals, as the above epigraph comedically outlines on pesticides and costly organics, are ever growing in late-capitalist contexts, and are entirely understandable. Soy is a ubiquitous presence in industrial products. Furthermore, it plays a concerning role in deforestation (Guerrero and Virah-Sawmy 2020; Levitt 2020) and in global agribusiness, as livestock feed for meat production accounts for 75 percent of all soy cultivated (Reveredo-Giha and Costa-Font 2021). Consumers wish to have access to information about what is in their food, and labels play an important role in purchasing decisions (Farris 2019; Michigan State University 2017). As capital interests outweigh consumer protections and confusion over product label meanings increases (e.g., “natural,” “organic,” “free from,” “high in,” “all natural,” “clean”), consumer trust declines. From food recalls to questionable regulation of vitamins and supplements, or concern over the health effects of cosmetics and beauty products, consumer interest in the ingredients of quotidian products has risen. In her research on the gendered ecoworry over toxins in everyday consumer products, from cleaning and beauty supplies to foods, Norah MacKendrick (2015, 60) argues that consumers often practice “precautionary consumerism” to “circumvent the conventional consumer landscape, which is characterized by a lack of precautionary decision-making by chemical producers, product manufacturers, and governments charged with overseeing chemical safety.”[3] Consumer soy avoidance is an example of such a tactic. Yet, as Eva Hayward and Malin Ah-King (2019) have argued in Toxic Sexes, addressing the gendered dynamics of toxic environmental exposures, popular narratives of purity can be equally problematic. By this I mean that soy phytoestrogens have taken on a particular meaning to consumers, one in which soy ingestion potentially harms or supposedly queers unknowing cisgender bodies. As the epigraph exemplifies, popular culture has come to be permeated by a language of purity and by fears of sex mutation and chemical castration by way of everyday products and foods.

Beyond the steady increase in vague consumer uncertainty, broad health concerns over phytoestrogens in soy, and a general decline in soy product desirability such as that described in Scientific American, there are numerous popular cultural examples of gendered ecopanic about this legume. These range from generalized ecoworry and rumors to outright conspiracy theory. For instance, a 2013 piece in Jewish periodicals Heeb Magazine and BaOlam Shel Haredim discussed rumored reports that a rabbi may have banned his students from consuming any soy products out of fear that it would lead to sexual arousal, advanced sexual maturity in young girls, or “gay sexual activity” (Anonymous 2013).[4] Also in 2013, known conspiracy theorist Alex Jones took this argument a step further to suggest that increased consumption of MSG and some soy and yeast products, as well as increased plastics leaching, all have potentially “catastrophic” queering as well as reproduction-interrupting effects. Jones has suggested that there is a US government "chemical warfare operation’’ on contemporary food products, which has resulted in larger numbers of gay people and prematurely reproductive young girls. In spite of inconsistencies in his line of logic (i.e., that such chemical warfare exists at all and would somehow result in both hypersexualized females and demasculinized or “chemically castrated” males), Jones’s brand of gendered ecopanic reflects aspects of popularized toxics discourse and moralized food panic about soy and other consumer products.

Revealing the underlying heteronormative and white supremacist tendencies of Jones’s argumentation, the moral panic of toxicity here is one in which all that is known or constructed as normative is considered under attack. However, Jones’s fearmongering begs the question of which bodies are actually under threat of chemical exposure or political restriction. Consider the economic and racial health disparities revealed by the Flint water crisis (in which poor Black citizens disproportionately experienced neurotoxic exposure to lead in municipal water supplies) and, more recently, by the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, national debates over transphobic legislation regarding the rights of transgender athletes, bathroom usage, gender presentation, and the harassment of parents of trans* youth continue to escalate from community schools to state legislatures and the halls of the Supreme Court (see Alison 2022; Peplow 2018; North Carolina General Assembly 2016; Stern 2017). The purpose of Jones’s most extreme example of conspiracy theorizing is not to engage gendered health disparities of exposure risks, or to underscore implementation of the precautionary principle of zero tolerance for exposure to toxic and harmful ingredients (Young and Seely 2015, 315). Rather, it underscores concern with the slippage in white, heteronormative patriarchy as status quo, by way of an unseen, largely undetectable chemical warfare against cisgender male bodies. Jones quips, “After you’re done drinking your little juice [boxes] you’re ready to go out and have a baby. You’re ready to put makeup on. You’re ready to wear a short skirt. You’re ready to go put together a garden of roses [or] to put lipstick on” (Jones 2010). The fact that both soy and MSG—long utilized in non-Western culinary traditions—are expressly discussed on the show and website reveals the racial and gendered dynamics of this popular toxics discourse that extends far beyond extremist cultural commentators to include broad ecofears about exposure (Barry-Jester 2016). Such commentary reflects troubling ideas about fixed “natural” bodies and presumes individualized health responsibility through “right” consumerism.

In their analysis of the moral panic that ensued from a food exposure scandal in the United Kingdom, food scholars Abbots and Coles suggest that panic is indicative of structural neoliberal emphasis on responsible consumerism in the food industry in which individual consumers are encouraged “to make ‘good’ choices” (Abbots and Coles 2013, 546). Mirroring MacKendrick’s research on the gendered pressures of precautionary consumerism, purity becomes a burden of consumer power, the outcome of moral correctness, and the naturalized trait of idealized foods that are imbued with goodness/cleanliness/purity (MacKendrick 2015, 60). In such instances, food, and specifically soy, is being used as a vehicle to reflect biologically determined, homophobic or transphobic cultural understandings of the body through contagion narratives, like the presumption that soybean consumption might somehow make one gay or more feminine. While not always accurate, popular ecomedia coverage of soy phytoestrogen ingestion has captured the consumer imagination in communicating some aspects of the broader, complex, and decidedly less attention-grabbing biomedical inquiry into soy products.

One might inquire if consumers are not simply (and rightfully) protecting themselves from a potential environmental threat experienced at the level of metabolic processes. Giovanna Di Chiro counters “econormativity” in antitoxics discourse and heteronormative framing in endocrine disruption research: “Thinking of the body as home/ecology, especially in consideration of those bodies, communities, and environments that have been reviled, neglected and polluted, provides an apt metaphor and material grounding for constructing an embodied ecological politics that articulates [diversity,] interdependence, social justice, and ecological integrity” (Di Chiro 2010, 200; see also Hayes et al. 2010, 2011). Di Chiro argues that feminist environmental work has at times reinforced ecoheteronormativity, and calls for “health of [all] bodies, homes, families and communities without reproducing the eugenics discourse of the ‘normal/natural’” (Di Chiro 2010, 200). Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson’s Queer Ecologies calls for a reorientation that “[critiques] pairings of nature and environment with heteronormativity and homophobia” (2010, 22). Arguments concerning the benefits or dangers of soy from an immediately toxicological perspective especially reveal this bias through their focus on racialized biologically determined reproductive and sexual capacities. Critical inquiry into the human hormonal effects of soy consumption is understandable given the immense number of studies reflecting varied corporeal outcomes of soy ingestion and isoflavone consumption. Consumers can only expect such inquiries to increase as pressure to shift toward meat-free diets and lower-impact crops rises. After all, even well-established restaurants and food publications like Epicurious have gone meatless out of a recent climate consciousness (First 2021; Treisman 2021). However, as nutritionist Mark Messina points out, it does not follow that human effects of soy consumption would be the same as nonhuman experiences, or that these documented effects—based on isolated, extreme levels of isoflavone consumption or tiny studies with inconsistencies—are automatic cause for concern in reproductive health, sterility, or virility in human bodies (Messina 2010, 2095; see also Cederroth, Zimmermann, and Nef 2012, 192–200; Bedell, Nachtigall, and Naftolin 2014).

Antisoy narratives perpetuate a risk discourse of femininity and queerness by virtue of their dominant “repro-centric” environmental position, as Sandilands and Erickson (2010, 10) articulate it—a position that “has been used to argue that the increasing prominence of transgendered individuals (human and more-than-human) is clear evidence of environmental contamination.” The analysis that follows examines how such narratives are commonly constructed and what assumptions they are built upon. Finally, I explore why this discourse proves a problematic barrier for imagining more inclusive environmental possibilities that envision the body less as im/pure and un/natural and more as an ever-shifting active ecology in an unprecedented era of human-induced environmental and climate change.

Soy as “Feminizing”

Beyond the ecopanic embedded in the specific fear of shrinking genitalia lies another concern over soy’s more general capacity for “feminization.” In February 2020, the Atlantic published an article on the rise of soy-based Impossible Burgers, vegetarian burgers that have been gaining in popularity for their faux “bleeding” effect and for their similarity in texture and flavor to “real” meat. Author James Hamblin (2020) reports, “some men believe that the primary ingredient in the Impossible Whopper and countless other vegan products will literally turn them into women.” Hamblin closely analyzes statements made by a livestock veterinarian bemoaning the “boob-growing” capabilities of soy in Impossible Burgers, comments that were later replaced with precautionary calls for “moderation” (Hamblin 2020). Such claims are not new, however, and they reveal a combination of cultural presumption concerning vegetarianism and its incessant associations with stereotypical understandings of femininity, and long-standing associations with what food scholar Emily Contois (2020) labels “dude food,” or what Carol Adams (2004, 43) famously labels the “reoccurring fact [of] meat [as] the symbol of male dominance” (see also Belasco 2007). In a 2009 Men’s Health article titled “Is This the Most Dangerous Food for Men?” interviewee James Price, described robustly as “a retired U.S. Army intelligence officer who once flew attack helicopters in Vietnam,” outlines the process of what he calls his “feminization” after isolating a three-quart-per-day soy milk ingestion. Price cites soy as the potential cause of his development of painful breasts, “flaccid” penis, plummeting sexual desire, “friend zone” status with new women in his life after his wife’s death, mood swings (particularly over emotional television shows), and sudden interruption in or loss of body and facial hair growth (Thornton 2009; see also Dr Steve, n.d.). Throughout the article, which reads like a nightmarish exposé outlining the ways in which average Cowboy Joes find themselves at the mercy of evil health food corporations, Price’s physical experiences are discussed in sharp, defensive juxtaposition to his internal and naturalized sense of self as hypermasculine.

Claims that soy consumption causes not simply an overall “feminization” but specifically “man boobs” are a reference to soy’s so-called estrogenic effect, which is a complex claim, at best, in the biomedical literature. Soy expert Mark Messina argues that gynecomastia is fairly common: “It is not merely excessive breast adipose tissue, rather it is a benign enlargement of the male breast attributable to proliferation of the ductular elements [and is quite] common, occurring in 50%–70% of boys during puberty and 30%–70% of men” (Messina 2010, 2096). The culture of body shaming in Men’s Health, among other popular media, uses the soybean to push against medical scholarship.

Food studies scholar Amy Farrell (2011, 10) aptly reminds us in Fat Shame that “all biological crises are also cultural crises [acting as] cultural sites where social power and ideological meanings are played out, contested and transformed. The ‘obesity crisis’ is no different.” Here size, gender, and social legitimacy merge through Price’s soy narrative. Additionally, such gendered and racialized assumptions presume fixed, naturalized bodies and negate important contextualized nutritional exposure differences. As Cederroth, Zimmermann, and Nef (2012, 192) argue concerning phytoestrogens and reproductive health impacts, “Asian populations have long consumed soy, mostly in the form of unprocessed food such as tofu or tempeh, whereas Westerners more commonly eat it either as dietary supplement or as a source of edible oil and protein substitutes [in processed foods].” The Men’s Health article uses terms like “working the land” and “standard American” to resist the so-called feminine and feminizing effects of soy consumption on an unwilling and unknowing normalized body—one that is decidedly white, heterosexual, cisgender, male, and of US citizenship. This factor is also certainly in line with some Global North nutritional associations of soy with vegetarianism and East Asian culinary traditions, and the very denigration of “true” masculinity rooted in anything other than meat-eating, Marlboro-man white masculinity, what scholar David Eng (2001) terms “racial castration” in his analysis of the feminization of Asian (American) men (see also C. H. Chen 1996).

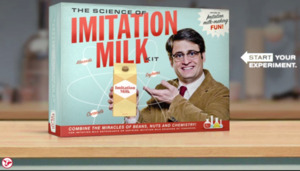

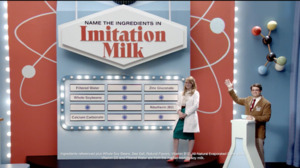

In other Global North-centric representations, dairy industry interests may also factor into popular fears over soy ingestion. For instance, ad campaigns put out by the American dairy industry have long referenced soy milk as less healthy, as chemically processed, and/or as more effeminate than the “real milk” consumers who guzzle cow’s milk. Industry representations problematize use of additional ingredients or processing in nut milks as opposed to the romanticized “purity” of milk straight from the cow. “Real” milk doesn’t need science or chemicals to make it something it’s not, or so the assumption goes. A number of “Got milk?” advertisements argue authenticity, proclaiming, “Real milk comes from cows” or “Many imitations, still no equal” (Bellatti 2012; California Milk Advisory Board and Deutch LA firm 2015). Others mock the oddness of nut-derived milks—sometimes referred to as “imitation milk” or “soy imitator beverage”—poking fun at impurity through inclusion of such things as the additive soy lecithin or higher numbers of ingredients (see figures 1–3; California Milk Processors Board, n.d.; Real Seal 2021; see also Rosenburg 2012; Associated Press 2015; Milk Processor Education Program 2016). Thus, here we also see the queer-bean-as-contagion narrative and a common racialized dietary construction working together (on vegetarianism, see Belasco 2007).

What Is It about Soy? Interweaving the Biomedical and the Social

Some previously published research can be downright scary, with claims that increased soy can mess with your hormones, the thyroid, and possibly cause cancer. [D]oes soy deserve that health halo, or should you swear the stuff off of your shopping list for good?

—Mary Grace Taylor and Kate Rockwood, Good Housekeeping, 2020

As the above quotation from the popular magazine Good Housekeeping underscores, there’s still a lot of nutritional concern widely circulated in gendered media like magazines or health and fitness websites about soy’s health impacts for modern-day consumers. What broad claims might we deduce from the ecomedia examples outlined thus far? Four key claims about soy ingestion are frequently interwoven within ecomedia, reflecting the broader popular imagination about soy ingestion. First, soy is essentialized as female derived and thus feminizing to male-sexed biology. Second, soy as an ingestible is being imbued with heteronormative meaning. Third, nutritional information about soy is confusing and ever shifting, exacerbating ecopanic. Finally, soy, the legume—rather than the various ways in which soy is industrially processed or the sheer quantities people may be consuming—is frequently misconstrued in health inquiries related to the isoflavones in soy products. What specific complexities connecting to the worry swirling around the humble soybean might we further examine within the biomedical literature, and what can that highlight for scholars of ecomedia?

First, soy is “feminized,” as in many of the previous popular culture examples, because of its estrogen content via isoflavones. Nutritionist Mark Messina discusses isoflavones as organic phytoestrogen compounds used as “possible alternatives to conventional hormone therapy” and in relation to “their effects in postmenopausal women” (Messina 2010, 2095). In a review of research on soy’s potential effects on men, Messina notes: “Isoflavones have a limited distribution in nature, and are found in physiologically relevant amounts only in soybeans and foods derived from this legume, although a variety of plants such as red clover are also rich sources” (2010, 2095). Frequently in ecomedia and in some biomedical narratives, the estrogen-like aspects of soy are specifically what is being equated with female-sexed embodiment and femininity. Thus, the very ingestion of estrogen is being equated as a feminizing, toxic force against the otherwise “normal” or “natural” ecology of (male) human bodies. This is what is happening when James Price emphasizes both the physical outcomes and soy’s supposed effects on his emotional sense of self as a heterosexual man in Men’s Health, and when Alex Jones expresses fear of feminization through plastic in juice box liners or the so-called skirt-wearing, lipstick effects of plastics leaching or MSG “chemical warfare” (Jones 2010). While there is case study evidence available to complicate this mythos further—specifically, high-dose animal studies I will return to momentarily—it is the very cultural agitation surrounding estrogen as sexed female, along with presumptions of female as automatically feminine, that I wish to underscore.

The very feminization of estrogen in the case of soy ingestion—as though all bodies do not already produce the hormone—makes for important interdisciplinary analysis. Estrogen itself in bodies assigned male at birth is neither irregular nor harmful, as some “20% of estrogen is produced via testicular secretion [or from] aromatization of androgens mainly in the adipose tissue, skin, and muscle” (Messina 2010, 2097). Though missing from more isolative studies of isoflavones,[5] a host of environmental, individual, and dietary factors studied in combination are key to better understanding effects of soy on diverse bodies, particularly as these effects may be heightened due to consumption factors such as dosage, quantity, cultural tradition behind usage, consumption timing, culinary preparation, individualized physiological processing of the three main isoflavones in soy (genistein, daidzein, glycitein), and agricultural or industrial processing. Messina (2010, 2096) reveals that “the possibility that isoflavones impair fertility has been a subject of discussion for [nearly 30] years.”[6] Yet, as underscored throughout the clinical review, these earliest effects were documented in female-sexed individuals of both sheep and cheetah species, and environmental and consumption habits proved core factors. Other studies did not account for factors such as extremely high quantities of ingestion; lack of any dietary variation; species differentiation; or cultural/dietary context. This emphasizes that “there is much species variation in the metabolism of and biological response to isoflavones” in human and nonhuman animals (Messina 2010, 2096). Studies of soy formula consumption in neonatal pigs and infant marmoset monkeys, as well as erectile dysfunction studies in infant rats, resulted in no direct links to common reproductive concerns about soy for human consumers when factors such as dosage, species differentiations, and individualized metabolic reactions were taken into account (Messina 2010, 2097–98). Later isolated studies in mice and rats fed “soy rich diets” suggested that the timing of exposure, whether in vitro or ingested from conception to adulthood, may result in “small decreases in fertility (litter sizes), testosterone production or sperm counts,” though not infertility, genital morphologies, or behavioral changes (Lehraiki et al. 2011; Cederroth et al. 2010). In contrast, Wen-Hsiung Chan’s (2009, 56) study in mice argued that soy isoflavone exposure in vitro effected mouse oocyte maturation, fertilization, and embryo development. What this might mean for human consumption is still uncertain, and the author likewise notes that “the precise regulatory mechanisms of embryonic developmental injury are unclear” (2009, 56). It is important to recall that nonhuman animal models are not the same as human models, and the pathways through which isolated soy isoflavones are administered in nonhuman animal models do not necessarily reflect the forms or sheer isolated quantities of ingestion that human beings are exposed to through diet. The science may prove isolated effects under highly controlled circumstances of ingestion in nonhuman subjects. This information is then being communicated and trickling down by way of popular environmental media to make new meanings about the so-called dangers of soy writ large. Thus, we must understand the interwoven dynamics of translations between and across biomedical data and ecomedia coverage.

Men’s soy consumption has especially resulted in an array of complex and nutritionally confusing results. The naturally occurring genistein in soy is what has long been studied in relation to its potential effects on human and nonhuman hormonal functions, and specifically as a potential endocrine disruptor with a range of studied effects on sexual dimorphism of the brain (Rosenfeld 2019; Sirotkin and Harrath 2014; Sumien et al. 2013; Kouki et al. 2003), in debates over male mammary gland development, or in possible disruptions to in vitro fertilization and embryonic development in mouse models (Messina 2010; Hamilton-Reeves et al. 2010; Chan 2009). Yet, as Chan (2009, 56) suggests, “the estrogenic and/or anti-estrogenic activities of [genistein] may reduce or enhance estrogen-dependent tumor growth, depending on the dose and timing of exposure.” Animal studies of soy ingestion have, in other words, arrived at a wide range of purported effects with a host of timing, tissue, and metabolic specificities that get lost in panic reporting. Moreover, as the Men’s Health article outlines, in spite of decades of medical, nutritional, and animal model studies of the possible health effects of this plant in human and nonhuman populations, the things with the most ecomedia sticking power remain fears of chemical or hormonally induced “castration,” as well as the development of what pop culture calls “man boobs.” Beyond the ecoworries of genital shrinkage and adipose tissue development, common reproductive concerns about soy ingestion include fertility loss, sperm and semen effects, testosterone decline, morphing sexuality, and increased or premature reproductive development. For instance, preliminary research conducted by Harvard scholar Dr. Jorge Chavarro (2008) suggested that sperm counts could be lower in men consuming fifteen isolated soy food products over a three-month period at a range of “nine possible frequencies of intake ranging from never or less than once per month to twice or more per day,” and especially in those men that researchers deemed overweight or obese. These findings have generated dynamic debate among biomedical researchers, and scholars have underscored key gaps in the study: the small scale of the study (ninety-nine participants in a single clinic); recollected participant soy intake (i.e., self-reporting) rather than long-term soy diet. Additionally, this study claiming negative impacts counters numerous other correlative findings that soy ingestion results in decreased cancer outcomes across sexes (see Vanegas et al. 2015; Chavarro et al. 2016; Rebar 2008; Willner 2020). This research did make it to the public limelight, so asking what role both the science and ecomedia might play in propelling such complex gendered concerns about soy is crucial.

Studies of soy isoflavone consumption in women have raised a wide range of interest and positive outcomes. The study of potential cancerous (specifically breast cancer) effects of soy consumption proved complex and/or highly impactful under further biomedical scrutiny (Power et al. 2008; Saarinen et al. 2006; Moorehead 2019). According to Messina, Nagata, and Wu, soy isoflavone intake may actually aid in tumor reduction through long-term consumption. They note, “There are several putative chemopreventive agents in soybeans and soy foods [and] considerable evidence suggests that soybean isoflavones are the primary […] agents” (Messina, Nagata, and Wu 2006, 1). Studies suggest that soy aids in increasing the response of mammary tumors to cancer drug Tamoxifen in rat models (Zhang et al. 2017). Studies of soy supplementation in people undergoing interventions using assisted reproductive technology found correlation of “significantly higher pregnancy and live birth rates” (Vanegas et al. 2015, 750). Still other research found that isoflavones may prove helpful in menopausal hot flash hormone balancing, alleviating bone-density loss associated with menopause, and decreasing the discomfort associated with vaginal atrophy (dryness) in menopausal women (see Zhang et al. 2017; Messina 2014; Hilakivi-Clarke, Andrade, and Helferich 2010; Cederroth, Zimmermann, and Nef 2012).

Likewise, the legume has proven helpful for heart health in all bodies. For instance, isoflavones consumed in conjunction with soy protein by young male macaques “[yielded] more robust LDL-lowering effects” (Bedell, Nachtigall, and Naftolin 2014, 228). Reviews of the biomedical data generally emphasize important positive effects of soy consumption, but also a need to separate the strands of exposure in research to look more closely at product and processing-specific factors, individual metabolism differences, and plant- and derivative-specific nutritional details. As Cederroth, Zimmermann, and Nef (2012, 198) argue, “One should not consider soybean, soy protein isolate, isoflavone as equivalent.” Conflating the legume with the different modes of its processing or deriving ingestible material are two very different factors. Consumers would do better to consider whether consumption of isolated soy proteins, alcohol-extracted soy protein concentrate, or soy lecithin alters soy’s possible effects on human health. We need more research on what type of soy is being ingested and what processing it has undergone. All of this is to say that the biomedical literature has proven complex and confusing, and that its selective trickle-down into popular media sources plays a key role in the nutritional alarm and confusion swirling around this legume. Paired with biologically deterministic distortions of gender and race, soy the legume has a questionable if not outright negative reputation at present.

Conclusions

We are all in chimeric borderlands where new forms of life are emerging. We are vulnerable to one another; our bodies are open to the planet.

—Eva Hayward, “When Fish and Frogs Change Genders”

Gendered food fear about soy is co-constructed through the science and through selective and wildly partial diffusion within ecomedia. In the above epigraph, gender studies scholar Eva Hayward comments on the influx of queer panic in media coverage of amphibian gender bending. Hayward presses readers to reconsider targeted anxiety, asking what it overlooks. Similarly reflecting on the so-called “transgender” frog question, Di Chiro (2010, 211) critiques heterosexism when she suggests, “the familiar ‘crimes against nature’ credo [invites] culturally sanctioned homophobia while at the same time sidelining and naturalizing ‘normal’ environmental diseases such as cancer.” In engaging ecopanic swirling around this legume, we must insist on asking other pertinent questions about its production and consumption. Consumers should remain critical of the potential everyday violence of toxics and the lack of transparency in consumer products. Nation-states must grapple with the effects of climate change and the specific impacts of industrial agricultural and land-use practices, which indubitably includes soy’s role in feedstock and deforestation. Yet we must also interrogate the problematic gendered assumptions upon which such ecopanic turns. Resisting normalization and authenticity rhetoric pushes panic away from assumptions of purity in food and beyond queer or reproductive-centric fear, onto more complex ecological entanglements of collective responsibility and possibility that acknowledge all bodies and health, not simply a select few delivered most commonly through “correct” consumer choices.

This is not to suggest that the solution lies in simple linguistic shift or in dismantling reproductive concern writ large. More work centering gender in toxics, exposure, and environmental health is necessary (see Scott 2015). We need amplified critical analysis of both human and nonhuman animal studies on questions of gender and exposure to emphasize a broader spectrum of bodily encounters, outcomes, and effects. A queered environmental imaginary is critical for pushing back against the fixed and “naturalized” to embrace all that is already permeable, vulnerable, and so-called “impure.” If faced with soy products in a supermarket aisle, how might consumers prioritize a more inclusive understanding of biodiversity beyond heteronormative, genitalia-centric biases while simultaneously resisting the health concerns being biomedically interrogated about soy? The food panic surfacing in the examples analyzed here assumes an uncontaminated or “pure to impure” food trajectory. The panic conflates the legume with its processing, assumes estrogen is female and feminizing, and seeks to isolate a single food rather than the broader confluence or cocktail of exposures. Ecomedia makes assumptions about which bodies are “under threat” and which are problematic, atypical, and abnormal.

Soy panic exposes the fickle nature of toxics discourse as producers and consumers navigate products and practices that may be toxic or fertility affecting yet also pleasurable, sought after, and desirable (see, for instance, M. Y. Chen 2012). Di Chiro (2010) suggests that there is an increasing normalization of environmental diseases like cancer. This analysis could be extended to include the selective normalization, even consumer pleasurability, of other sources of potential toxic exposures: cars, fashion, household cleaning products, building materials, foods, cigarettes, alcohol, antibiotics in meat. Environmental futurities that are not inclusive of a variety of bodily “natures” reinforce reproductive-centric and homophobic or transphobic exclusions. On toxicity in plastics, Max Liboiron (2016) also reminds readers of the present state of certain exposure levels: “It is no longer possible to establish uncontaminated control groups [for marine plastics research].” The hard line between pure and impure, “natural” and “unnatural,” is always and already much more complex than such discourse establishes. Hayward (2011) and DuPuis (2015) remind us that bodies are always permeable and vulnerable ecologies, a reminder that shifts both the single-contaminant assumptions and the purity logic of soy panic. This is to say, we resist the violence of queer panic and fear of “the feminine” by acknowledging that such anxiety erases the real, material implications of environmental pollution and equality in health for all bodies. Further, by carefully balancing both the cultural and the biomedical together, a more complex picture emerges of soy’s bodily effects. Emphasizing dietary context, timing, and dosage is absolutely key.

Panic narratives overemphasize reproductive, genitalia-centered, and toxicity fears. Moreover, they tend to ignore important medical findings on the legume’s significance that range from its chemopreventative impacts, antihypertensive outcomes, and tumor reduction to increasing comfort for menopausal women including hormone therapy, bone density improvement, hot flash reduction, and reduction of vaginal dryness (Sirotkin and Harrath 2014). Emphasizing ways to embrace such important and complex nutritional nuances permits a focus on systemic changes of neoliberal agricultural practices, policies, and food industries, rather than targeting a plant or an identity.

I recognize a complex relationship to estrogen consumption in diverse trans* communities, which is beyond the current scope of this article to address, but which begs further critical inquiry on soy phytoestrogens. I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for thoughtful insight on inclusion of this topic. More research is necessary to understand differences across phytoestrogen versus estradiol usage for hormone treatment purposes. For research on use of oral estradiol in transitioning, see Deutsch, Bhakri, and Kubicek 2015.

I am especially indebted to Eva Hayward and Malin Ah-King’s (2019) conceptualizations of toxicity and “reactive sexing”; to Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson’s (2010, 22) Queer Ecologies and Giovanna Di Chiro’s (2010, 200) “Eco-normativity” as theoretical frameworks underscoring a queer ecological call for “challenging hetero-ecologies from the perspective of non-normative sexual and gender positions.” Kim Hall’s Towards a Queer Crip Feminist Politics of Food (2014) pushes back on the ableism, moralism, and purity rhetoric often associated with narratives of what and how to eat; and Julia C. Ehrhardt’s (2012, 239) work also proves of import by arguing the relevance of queering the field of food studies “to enrich our understandings of the interrelationships among food, gender and sexuality,” revealing how many food analyses “may reflect unintentional heteronormative biases.” Jane Bennett’s (2010) and Stacy Alaimo’s (2010) work on vitality, matter, agency, and questions of entanglement and exposure inform this article’s framing of the layered ways in which cultural ideas about soy and the matter of soy phytoestrogens are lively and entangled across the body, media, and society.

For critiques of precautionary consumerism, see Alex Zahara’s (2019) excellent short piece “Queering Chemicals (EDCs).”

The veracity of this claim came under fire in 2013. I include it to convey the sheer range of fears and claims about soy.

What I mean by isolative studies are those that isolate the main isoflavones, essentially taking soy out of the broader combination of factors that might impact its metabolism.

Thirty years more accurately reflects the time elapsed to date in the literature discussed.