Pattie Gonia is a drag queen and environmental advocate. Stomping on gender norms in her black patent leather, thigh-high stiletto boots, @pattiegonia (she/her as Pattie; he/they as Wyn Wiley, Pattie’s creator) has amassed more than 346,000 followers on Instagram as of August 2021. She uses her Instagram platform to promote ethical consumerism, share resources on the climate crisis, and endorse a brand of intersectional advocacy that works to destroy the exclusionary practices of mainstream environmentalism and outdoors/adventuring culture. Pattie’s desire, according to a feature in Self, is for “queer people and anyone on the spectrum stepping into the outdoors to feel like that space is theirs to find out a little more about who they are and enjoy their lives” (McCoy 2018). With playfulness and positivity, Pattie makes clear that her account is primarily for education and advocacy: “We all just want to be entertained when we open our phones and go to Instagram, but if we can be entertained and get a little dose of Oh, that challenges my thinking a little bit, or That’s a little bit inspiring, that’s beautiful” (McCoy 2018).

Instagram is an effective venue for Pattie’s messaging, because the instant gratification afforded by social media blends with her eco-advocacy. For example, Pattie’s “thank u, next” post from November 23, 2018, features the over six-foot Wyn out of drag in Pattie’s signature black stiletto boots and hiking poles atop a peak in Yosemite, kicking and vogueing away environmental threats like POLLUTION, STRAWS, and DEFORESTATION, and set to the Ariana Grande hit “thank u, next” (figure 1). The video was a contribution to #optoutside, an anticapitalist, proenvironment response to Black Friday. Pattie uses the video to encourage stewardship and teach her followers about everyday ways they can help fight climate change. The post has well over 400,000 views as of August 2021.

Pattie devotes her Instagram account to ecodrag, which seeks to dismantle gender essentialism and challenge oppressive narratives of “natural” masculinity. Since gender, including masculinity, is, to invoke Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990), always already a performance, ecodrag is multitudinously subversive. Ecodrag has the power to disrupt fixed notions of gender by making the gender binary both instantly recognizable and clearly performative; undoes notions of an exclusive outdoors experience belonging only to the realm of the hetero/hypermasculine; and plays with a new narrative of drag that seeks to work in concert with the “natural.” While drag queens have been at the forefront of various political protests and campaigns for decades, ecodrag, with its link to social media activism, has only just started to communicate the urgency of the climate crisis. Pattie’s drag makes obvious the queer performativity of nature that, to invoke Karen Barad (2011, 124), calls for an accounting “not only of the materialization of ‘human’ bodies but of all matter(ings)/materializations, including the materializing effects of boundary making practices by which the ‘human’ and the ‘nonhuman’ are differentially constituted.” This queer performativity “cannot take for granted that all the actors, actions, and effects are human” and originates from the necessity of “a way of thinking about the nature of differentiating that is not derivative of some fixed notion of identity or even a fixed spacing” (Barad 2011, 124). Thus, Pattie uses her drag persona to lay bare the performative aspects of masculine stereotypes at the heart of American outdoor culture and mainstream environmental thought. Her “DRAGCTIVISM” relies on “the actions of allyship,” as she flings away things like racism, climate change deniers, financial barriers, and styrofoam in her “gender bending zelda realness” drag (@pattiegonia, July 30, 2020). Calling on her followers to “work in solidarity to rid the outdoors and our climate of all forms toxicity [sic],” Pattie reiterates that the work begins by challenging the gender binary (@pattiegonia, July 30, 2020).

This article looks broadly at Instagram’s potential as ecomedia, before turning to the concept of an ecoqueer Instagram, which seeks to undo fixed and essentialist definitions of nature and gender. I examine the social media channel’s potential as an ecoqueer venue with the potential to reach historically marginalized people. Redefining human encounters with the nonhuman world and observing how gender/sexuality are bound up in notions of the natural are hallmarks of queer ecology in general and ecoqueer Instagram in particular. Finally, in offering a further analysis of Pattie Gonia, as both an ecoqueer Instagrammer[1] and an ecodrag innovator, I examine the way her ecodrag performances and social media activism work against the restrictive, white, heteropatriarchal, capitalist expressions of masculinity in the wilderness. Pattie advocates for a queer, intersectional space that confronts the violence of racism, ecophobia, and homophobia. Her drag relies on exposing the ways her advocacy is not only a performance but also a means of making legible how all our actions are performances of some kind.

Instagram as Ecomedia

Most of the theorizing on ecomedia tends to focus on the environmental messaging in film, television, and advertising. As such, explorations of Instagram as a dynamic, if at times ambivalent, venue for environmental awareness are still nascent. Even harder is gauging and assessing if and how social media activism can change attitudes and behaviors. But at its most basic level, social media plays a huge role in how various communities see themselves in an outdoors space still inaccessible and unsafe for some. Referencing the 2006 “green issue” of Vanity Fair, which included only three BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) among its eco-activists, Carolyn Finney (2014, 2) argues that the “representation of environmental issues and the narrative supporting the visual images provides insight into who Americans think actually cares about and actively participates in environmental concerns. In addition, how the environmental narrative is portrayed will be an indicator of who is actually being engaged in the larger conversation.” In other words, if people are not seen as caring about or engaging with environmental issues, if there are no established narratives of accessibility on which marginalized people can rely, they are automatically excluded from outdoor spaces. In a perfect world, Instagram and other social media platforms can act as a catalyst for reconstructing the world, and it seems that ecoqueer curators have been busy doing that work already.

Broadly speaking, whether social media activism (alternatively called hashtag activism, clicktivism, or slacktivism) is actually an effective means of creating change is still up for debate. An article in Science compiles evidence that those with left-leaning politics are predisposed to offline action and tend to use “transmedia branding” in their own online protests (Freelon, Marwick, and Kreiss 2020, 1197). Further, while individual commitment to certain issues “is undoubtedly low […] the aggregate crests of attention generated by thousands or millions of such actions can catapult a protest movement from obscurity to international prominence” (Freelon, Marwick, and Kreiss 2020, 1197). This means that activism exists on a wide spectrum, ranging from sharing information with social media contacts to community demonstrations to lobbying for legislative change. The power of signal-boosting and virtual conversations to change people’s hearts and minds, or get them to act, awaits further study. Yet, as social media remains one of the primary means of communication in the contemporary moment, we need to pay attention to how social media communicates and frames social and environmental justice causes.

Simon Estok (2017) asserts that ecomedia in general tends to replicate the familiar narratives of heterosexism, misogyny, and ecophobia and embrace “the humanistic narcissism, which will always prevent any change for the better, a narcissism of which the term ‘Anthropocene’ freely indulges” (5). Yet Instagram as ecomedia provides an essential space for representations of how to be outside and take up space in parks and green spaces. Recreation ecologist Ashley D’Antonio (2019) explains that “[m]ost of the visitors to our parks and protected areas are upper middle class, white and slightly older. […] There’s been a lot of groups that use social media to get more people of color, or people that aren’t traditionally seen in our protected areas, out promoting and saying that this is a space for you, too” (Hegyi 2019, n.p.). The National Park Service reports a 37 percent increase in the number of visitors since 2010, when Instagram was founded. D’Antonio notes that no study exists on the impact of the increased car and foot traffic on these protected areas, but the need and the desire to “escape” into green spaces and see themselves as environmental actors remain important for people of all backgrounds. In fact, Ailsa Walsh (2018), writing on behalf of the Center for Outdoor Ethics/Leave No Trace, suggests that Instagram media can encourage stewardship and make the outdoors appear more inclusive and accessible to marginalized groups (BIPOC, LGBTQ+, the disabled, the aging, the poor). Furthermore, if used in respectful and mindful ways, social media can be “a powerful tool that can motivate a nation of outdoor advocates to enthusiastically and collectively take care of the places we share and cherish” (Walsh 2018, n.p.). Leave No Trace’s own Instagram feed frequently highlights one of its main principles—pack it in, pack it out—often signing off their posts with the encouraging and self-possessive hashtag #enjoyyourworld.[2]

But the paradoxical push to #enjoyyourworld and protect it at the same time is at the heart of some versions of Instagram’s ecological awareness. According to Christopher Ketcham (2019), Instagram has “ruined the Great Outdoors.” Users and influencers who purport to value the outdoors instead consistently exploit it for their own profit through “a perverse irony that seems lost on them” (Ketcham 2019, n.p.) He abhors the “herd instinct” that turns areas of “stunning natural beauty […] into a morass of crowding” (Ketcham 2019, n.p.). Ketcham makes it clear that no explicit environmental advocacy could stem from social media engagement. Madeleine Gregory’s (2019) response to Ketcham’s diatribe points out that the outdoor community, long the exclusive realm of white, cis, educated, wealthy, able-bodied men, becomes more accessible to minority groups when they see themselves represented in online communities via platforms such as Instagram. This dominant narrative of nature promotes practice of an “everyday eugenics,” to invoke Katie Hogan’s (2010, 245) term, which “flows from protectionist discourses of nature and the environment” and “institutionalizes exclusionary practices.” According to Gregory, the real problem is not the social media users of Ketcham’s maligned ilk, but the systemic undervaluing of universal access: it is that “tricky balance between encouraging visitation and prioritizing conservation [that] isn’t a new concern—it’s always been central to the mission of public lands. That mission is being jeopardized now more by understaffing and a lack of funding than by Instagram posts” (Gregory 2019, n.p.).

Access to public lands is not a privilege you earn, nor should accessibility be meant for only the few, Gregory further notes, since the entire purpose of public lands is that they are for the use of all people. Danielle Williams (2019), writing for melaninbasecamp.com, points out that users who openly refuse to geotag their locations via social media applications—one of Ketcham’s solutions to the invasion of outdoor spaces—are enacting a form of gatekeeping. This racist, ableist, and elitist practice becomes a marker of various forms of privilege: “The pushback against geotagging involves ordinary people deputizing themselves and asserting authority they don’t actually have to keep the outdoors ‘pure’ or ‘wild’, ‘pristine’ or simply, the way they remembered it from childhood by excluding people they view as dirty, loud, offensive, or simply not sharing their values” (Williams 2019, n.p.) Geotagging is just one small way the outdoors can open up for marginalized people. Within our collective imagination, the settler myth of the “pristine wilderness” initiates the idea that outdoor spaces are not only reserved for the few but also simply there to be exploited for capitalist profit by those few.[3]

Whether or not messaging and the images presented on social media platforms translate into practical, effective environmental activism is moot. What is more important on social media platforms like Instagram is how they can convey some version of instantaneous democratization. The visual modeling of the platform along with its open accessibility means that eco issues like single-use plastics and ethical consumption connect with faces and performances not always valued by elitist narratives.

Queer Ecology and Ecoqueer Instagram

In his paradigm-shifting essay “The Trouble with Wilderness,” William Cronon (1996) makes use of the mirror as a metaphor, noting that when we look into it, “we too easily imagine that what we behold is Nature when in fact we see the reflection of our own unexamined longings and desires” (7). The “trouble with wilderness,” in Cronon’s estimation, is that it is an entirely human invention, one that evolved in the colonial era as something “to be ‘deserted,’ ‘savage,’ ‘desolate,’ ‘barren’—in short, a ‘waste,’ the word’s nearest synonym” to the more sublime notion of nature as something to evoke “bewilderment or terror” (8). The later movement to protect America’s “wild” lands and to establish a national park system emerged in a time of paranoia and fear: fear that the frontier myth that defined American “rugged individualism” (read: “heroically masculine”) was being erased, fear that all that was sacred and sublime, “virgin” and “pure” about the outdoors would be replaced with what was dirty, disgusting, other, effete, unmanly, and, essentially, un-American. This troubling aspect of the frontier as “the natural, unfallen antithesis of an unnatural civilization that has lost its soul” means reproducing “the dualism that sets humanity and nature at opposite poles. We thereby leave ourselves little hope of discovering what an ethical, sustainable, honorable human place in nature might actually look like” (Cronon 1996, 16, 17). Offering diverse narratives of encountering the nonhuman world that undoes protectionist discourses is just one of the main jobs of queer ecology.

Queer ecology prioritizes nonessentialist approaches to gender and sexuality, decentering and troubling ideations of traditional masculinity and how it aligns with paradigms of the wilderness, the outdoors, and the “natural.” In her groundbreaking essay from 2005, “Unnatural Passions?: Notes toward a Queer Ecology,” ecoqueer theorist Catriona Sandilands observes that public outdoor areas were first established to help restore elitist, ableist white masculine recreational pursuits, emptying the lands of Indigenous populations and further reinforcing systemic racism and sexism: “ecofeminism and environmental justice open our eyes to the fact that nature organizes and is organized by complex power relations. What queer ecology adds is the fact that these power relations include sexuality” (Sandilands 2005, 6).

Historically, outdoor spaces are also tied to discourses of stereotypical “manly” or “butch” men. Nicola von Thurn’s art series boys will be boys from 2011–15 highlights this association between men and nature. boys will be boys includes self-portraits of the (woman) artist in “traditional” manly outdoor occupations—hunting, lumberjacking—“to reveal stereotypes: stereotypes of male dreams, of a life in the wilderness—a far cry from civilization, in a seemingly wild landscape that appears as unreal and synthetic as the dreams themselves. Dreams constructed by society, by media, by advertising. […] where men are the masters and protagonists” (Von Thurn 2017, 87–88). Or recall another example, the 1903 rugged camping trip between bro-president Roosevelt and John Muir that helped lead to the founding of the National Park Service. Historians like Peter Boag (2003) argue that “idealized democracy and heterosexuality reinforced each other,” so that early republican notions of naturalized (hetero)sexuality helped form the bulk of American domestic policy in the early centuries, causing paradigms of “[t]he masculine that inhabited the public realm” to seek “to transform natures or wilderness into fruitful farms and productive towns” (53, 48). He frames Mount Rushmore as a metaphor for the convergence of dominance over Indigenous peoples and the nonhuman world with heteromasculinity.[4] There is a cementing in popular memory between masculinity and “rugged” recreation, health, dominance, and, by extension, abuse.

Nature has no gender, but we tend, in a patriarchal world, to assign gender to all manner of activities and inanimate objects. This ideological construction creates a representational paradigm whereby heterosexual white manhood (i.e., “real men”) is construed as the most “natural social identity” in the United States. As Mei Mei Evans (2002) argues, [T]he “‘true American,’ the identity most deserving of social privilege” is connected to the “strategic deployments of Nature and of the ‘wild’ […] ‘naturalizing’ and thus privileging straight white men in US society since ‘discovery’” (183). “The same paradigm,” Evans further lays out, “has led to notions of some folk as being less deserving than others not only of access to nature but of the right to clean, uncontaminated environments in which to live and work” (187).

Ecoqueer Instagram accounts that show people taking up outdoor spaces, like @out4s, @unlikelyhikers, @theventureoutproject, @indigenouswomenhike, and @qpochikers, broadcast a powerful message about the right of the “other” (read: BIPOC, fat, disabled, trans, etc.) to access the outdoors. Establishing and adopting spaces for queer occupation, as Gordon Brent Ingram (1997) argues, can institute possibilities for liberation and community-building, “at least in terms of greater visibility, some increase in freedom of behaviour, and the lowering of perceived risk of assault or other forms of repression” (95). Specifically, Ingram refers to outdoor space as particularly strategic to queers because it is “almost a home, because there are few other places to go” (101). The terms Ingram invokes here echo the idiom of the ecoqueer, as the cooperation between the nonhuman world and queers draws attention to particular environments (like, for example, outdoor spaces) as specifically adopted for the transgression of and liberation from normative behaviors. Showing up on Instagram, occupying space, and projecting representations of historically marginalized groups are often the first steps toward environmental stewardship. An ecoqueer Instagram centers narratives of eco-advocacy and environmental justice issues of marginalized people in order to shape visual, community-driven messages of equity and sustainability.

Ecoqueer Instagram curators tend to place an emphasis on montaging images of queer and nonhuman life, representing themselves taking up space in the outdoors, and demonstrating a permeable and mutable relationship with elements of the nonhuman world. These curators make legible a broad range of themes—zero waste, plant culture, ethical consumerism or capitalist resistance, rural spaces, interspecies relations, the accessibility of backpacking and hiking, and Indigenous rights and decolonization—but they all share a goal of spreading ecological advocacy through visibility and virtual coalition-building. In a time when one version of mainstream queer masculinity is dominated by images from the “new spiritual consumerism” of the Queer Eye guys (the term employed in a New York Times piece from August 2019 by Amanda Hess) and when straight, cis men tend to shun ecofriendly green practices because of their associations with “green femininity” (based on a Journal of Consumer Research study from August 2016 by Aaron R. Brough et al.), ecoqueer Instagram is shaping an urgent message of sustainability for all of the earth’s beings and lifeways. In the words of @queerecology, one of the main points of the ecoqueer lies in “[c]ollectively imagining an equitable, multispecies future,” according to their Instagram bio. Or, as Michael Morris explains, queering ecocriticism means “the potential for reconfigurations of the living material world, as well as articulations of other possible worlds of life and livability” as well as a general practice of “destabilizing regulatory norms of heterosexism that are naturalized through social (re)productions in which lives and livability are constrained along the axes of binary” (90).

Pattie Gonia

Pattie Gonia is an ecoqueer Instagram curator. Though she is not the first or the only ecoqueer Instagram curator, her rapid popularity signals a pushback against various forms of eco-oppression being represented in the media. Pattie’s main purpose is to revise the overriding images of the outdoorsy nature lover whose most visible iteration takes the form of a white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied man of a certain age who often performs supremacy and domination over the nonhuman world. Greta Gaard’s (2014) consideration of alternative ecogenders starts with calling for an ecomasculinity that opposes the Westernized view of “male self-identity and self-esteem based on dominance, conquest, workplace achievement, economic accumulation […] and competitiveness” (227). Pattie Gonia’s ecodrag seeks to disrupt notions of hypermasculinity that favor aggression and dominance toward the natural environment, in favor of a more cooperative, holistic, conscientious relationship to the environment. The fluidity of her gender expression is the most self-evident element of her performance, and toxic masculinity, which she consistently refuses, shows up to destroy joy, restrict free expression, and commit violence.

With another photo of herself in midtransformation (full makeup but without a wig and still in Wyn’s hiking outfit), Pattie issues a “REMINDER: your outdoor adventure doesn’t have to look like the toxic masculinity peak bagging narrative that the majority of the outdoor industry/community thinks is the ‘worthy’ way to get outdoors” (July 8, 2020). Pattie frequently shows herself in this liminal, in-between, pre-drag space, as a way of telling her followers: “it will always be a daily battle to snap myself out of years of societal and self inflicted femme shaming and toxic masculinity. but how dare a queen critizize [sic] the masculinity and femininity inside of them and how dare you do it to yourself either” (@pattiegonia, May 4, 2019). Pattie is self-reflexive and explicit that her drag is an essential part of Wyn’s political expression, situating it within her intersectional advocacy and making clear that “drag would not exist with out [sic] a lot of things like black femme queer men, but it also wouldn’t be a thing without women. […] women: your energy, your love, you being here, it matters to me. it keeps me creating. it keeps me having fun and the world just needs a smidge more fun, right?” (March 8, 2020).

Drag is Pattie’s way of not just playing with conventions and troubling the gender binary but also destroying assumptions about masculinity and doubling herself, showing the power of being able to perform gender on an infinite scale. “Are you feminine or masculine?” a follower asks in one of Pattie’s DM. “No, are you?” Pattie quips, revealing her answer overlaid on a diptych photo of Pattie as a cowgirl with pigtails and red, thigh-high patent leather boots alongside Wyn, shirtless and in a cowboy hat, gazing into the sunset (November 17, 2019). “Mother Nature sees no gender,” another diptych states, showing Pattie with long red hair and an autumn leaf crown and Wyn in a windbreaker and bare faced (November 2, 2018). In fact, in an act of self-love, affirmation, and subversion of the institution of marriage, August 13, 2019, became Wyn and Pattie’s wedding day. Pattie and Wyn are “married” atop a mountain peak, and their joyful celebration of accepting themselves and all that entails comes via a video that spoofs a Bachelorette-style car ride and ultimate reveal by the bride. The caption invokes #lovewins, situating Wyn and Pattie’s private love story alongside public celebrations of marriage equality.

Assessing Pattie’s impact as an ecodrag performer might be difficult, but her drag is powerful because, as any good intersectional advocate should do, she acknowledges her own flaws and checks her privilege often. A long post from January 9, 2020, shows Wyn half in drag, looking at his reflection in the mirror, and admitting to multiple types of privilege from which he benefits—skinny, white, socioeconomic, straight passing, among others—and pledging to use his privilege to help others. Never afraid to show her own journey as an advocate, she argues that the “lies, often from people who used shame, fear and gatekeeping as some form of fake environmental wokeness that if i wasn’t trying in all areas, all the time” caused her to see herself as a failed advocate until she learned to reframe

my definition of advocating for mother natch and i’ve left titles behind too- i don’t need the climate activist badge (plot twist…there isn’t one) and i’ve found new ground in redefining what caring for our planet looks like to me. starting to care isn’t going to look like waking up tomorrow and never using plastic again. what it’s actually going to look like is waking up and choosing to give 1% more shits in one area in your life. (October 18, 2018)

Most often, Pattie puts her allyship into action by using her platform to raise money for other organizations seeking to make the outdoors more equitable. Pattie/Wyn has partnered with NOLS, a wilderness school, to fully fund fourteen scholarships for LGBTQ+ youth and to lead a trek through the Utah canyonlands for two weeks. On #givingtuesday of 2020, Pattie and her community (along with corporate partners like Brooks Running and Miir Drinkware) raised more than $205,000 for organizations like @hbcusoutside and @wilddiversity. “you know you want to be that bitch that donates,” Pattie calls out her supporters (@pattiegonia, December 1, 2020).

An announcement on April 8, 2021, unveiled Wyn’s contribution as photographer and organizer of @backcountry’s Trailblazers program. The program provides money for BIPOC educators and advocates of equity, diversity, and inclusion in the outdoors. Inspired by @greengirlleah, who began the @intersectionalenvironmentalism account in June 2020 and is publishing an edited collection entitled The Intersectional Environment (which Pattie shouted out on her account), Pattie frequently insists that the environmental movement is incomplete without an examination of racism. In the summer of 2020, in response to the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Pattie used her platform to raise more than $116,000 for various organizations that provide access and safety for BIPOC in the outdoors. Pattie shared the “Whiteness in the Outdoors” slideshow, compiled by various BIPOC Instagram curators, that highlights the insidiousness of racism in the outdoors. Encouraging her followers to share the information and challenge others to examine their own privilege, Pattie frequently reminds other allies that allyship is an ongoing, daily practice not intended to “make you feel all warm and fuzzy inside; it’s to make you UNcomfortable. allyship’s purpose is to open your eyes to the injustices of the world and incite you to act” (June 12, 2020).

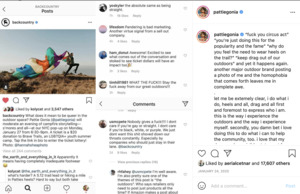

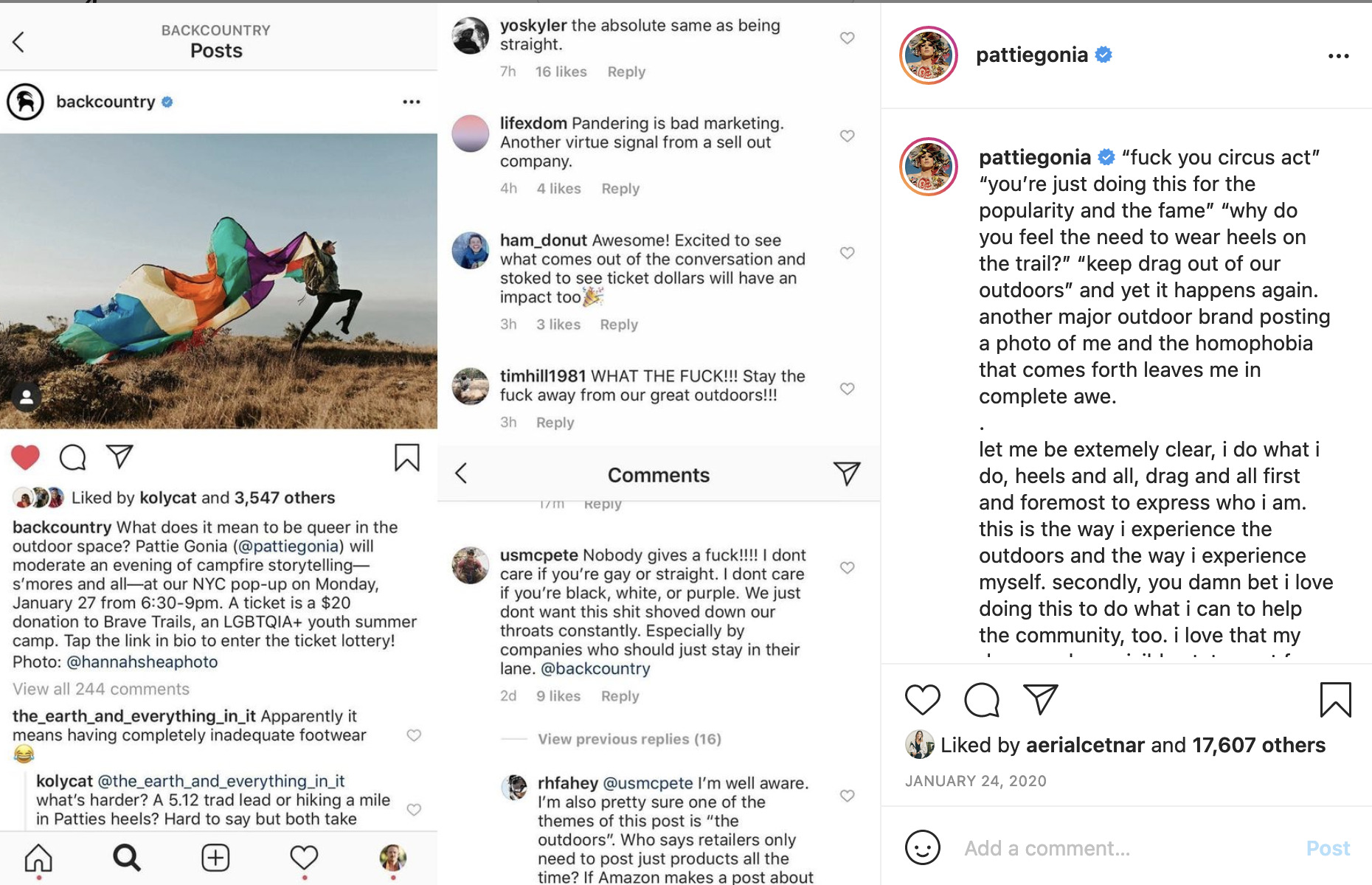

In January 2020, @backcountry, the outdoor outfitting company, received antigay backlash for hosting a pop-up event to raise money for Brave Trails, the outdoor adventuring organization that provides safe outdoors spaces for LGBTQ+ youth. Pattie moderated the panel at the pop-up event, and her Instagram response outlines her drag as liberatory self-expression as well as “a visible statement for the LGBTQ+ community in the outdoors. ESPECIALLY for those LGBTQ+ people who experience more hatred and homophobia for who they are because unlike make up or heels, they can’t wipe off pieces of who they are like i more easily can” (January 24, 2020). This is a reference to Wyn’s straight-presenting privilege, a privilege he eschews while in drag as a way to illustrate the inherent fluidity of gender expression. Pattie urges her queer followers “TO BE VISIBLE AS HELL. […] to use your voice, and to take up space. fuck shit up and do it with as much love and grace as you can muster even though you’re pissed as hell” even in the face of the “haters” who “are making the outdoors an incredibly unsafe space for people like me” (figure 2). Here, verbalizing and performing visibility is an essential step in equitable and queer-friendly stewardship. The heart of Pattie’s message is that queer people not only belong in outdoors spaces but also are entitled to safety while there. Her eco-advocacy insists on access for all, free of the toxicity of dominance, violence, and control.

The top comments on this post are overwhelmingly supportive of Pattie’s position, including one from @_trail_mx_, “a queer trans woman” who expresses appreciation for such visual markers as a rainbow on another trail hiker’s backpack for helping to alleviate the otherwise “unnerving” experiences of the outdoors. Another comes from @deafclimber, who applauds Pattie for calling out the toxic language for outdoor adventurers of all abilities. Comments like these, in spite of the virtual nature of Pattie’s advocacy, are a powerful signal of Pattie’s reach. Pattie often encourages her followers to not just share content, comment on posts, and follow others but also educate themselves and others, donate money, and personally engage with causes when there are calls to action. Whether in full-on glam drag, half-dressed drag (no wig, but some makeup), or costumed in upcycled sleeping bags, dressed as a Girl Scout or National Park Service ranger, or wearing two fanny packs as a bra and using the hiking trail as her runway (figure 3), Pattie broadcasts edifying snippets of information and forces her followers to confront their destructive habits while empowering them to use the trail as their own runway.

The vivacity and boldness of drag, its inherent politicalness combined with the urgency of ecological messaging, means that Pattie is able to effectively “dress up” the messaging and play with fashion as a way to challenge the arbitrary divisions between “high” fashion and couture and, well, trash. In a “haute couture, runway worthy, mother fucking dripping-in-sweet-n’-sour-sauce-from-the-chinese-take-out-that-was-in-the-bag-previously delicious dress” made of 200 THANK YOU plastic bags, Pattie stomps to HotSpanish’s refrain of “Louis, Gucci, Prada” (@pattiegonia, May 2, 2019). Performing in front of a Prada storefront in a desolate stretch of desert, Pattie in this post simultaneously critiques the addiction to single-use plastics as well as the fashion industry’s rampant negative impact on the environment. Pattie takes on the issue of single-use plastics again via her Marie Trashionette look (figure 4). The look comprises the single-use containers Pattie and two friends disposed of during the COVID-19 quarantine and was featured in Out magazine’s “out100 of 2020” spread. Pattie’s invocation of the French queen’s excess is doubly significant: the issue of the disproportionate amount of waste developed nations produce exists alongside the fabricated splendor of a long-failed system.

These high-fashion moments lay bare the truism that social justice advocacy is not always pretty. Pattie’s practice of showing herself in a half-drag state, sometimes covered in trash, and displaying her vulnerabilities is a meaningful way to begin the conversation about environmental equity for LGBTQ+ folx. She is not afraid to amplify the voices of other marginalized people on her account, acknowledging that her drag and allyship are always in progress. Making ecological action accessible, she wants other nature lovers to know: “it’s not some far off eco-neverland, it’s a practical place where you can start and, GUESS WHAT, you likely already have. that is powerful. that’s what caring for our planet really looks like. the daily micro decisions that make up all of our lives because at the end of the day, that’s all we’ve got” (@pattiegonia, April 27, 2020).

Pattie’s performances embrace a “gaiety, irony, and frivolity that have been sorely lacking in environmental movements [and] could prove crucial to such movements” (Seymour 2018, 114). Nicole Seymour further notes that queer environmental performances not only “reanimate environmental conversations by affiliating with nature, environment, and the nonhuman ‘improperly’: not through ‘dreadful seriousness’ or reverence but through modes such as gaiety and frivolity” but also with an embrace of “‘low environmental culture’: art that is accessible, nonhierarchical, and lowbrow” (115, 114). And is there anything more lowbrow than our communications via social media? As just one example, Pattie gets into drag to call out Candace Owens, a right-wing pundit, who tweeted in November 2020 about the “outright attack” of the Marxist feminization of men in the West that would lead to a breakdown of society, a reference to a Vanity Fair editorial showing Harry Styles wearing dresses (Owens 2020). Kitted out in her famous outdoor gear drag and climbing equipment (figure 5), Pattie critiques Owens’s hate and intolerance, likening it to a drag performance that actually replicates hegemonic and unrealistic notions of masculinity. Pattie’s cheeky and coy pose in this post belies the serious challenge to Owens’s toxicity, and by turning the critique back at Owens, using language that would likely infuriate her, Pattie proves that drag is innumerable and mutable. Owens’s intolerance is fueled by lies (read: cultural norms) and is decided against humanity’s essential state of love and acceptance, according to Pattie.

Posts from Pattie as Mother Natch from October 2020 help prove her playfully nonessentialist point. In one video, Pattie emerges from a pile of autumn leaves with a leaf headdress and full Mother Natch makeup, and in her Pattie voice gleefully squeals: “It’s my favorite season—Election season!” Quickly changing the timbre of her voice to a lower, more masculine register, Pattie holds up her VOTE sign and simply states, “Vote, bitches.” In the second video, Pattie spoofs influencer makeup haul/unboxing videos, a genre that has become popular on Instagram and YouTube and that usually features some influencer who has been paid to “unbox” (usually skincare and cosmetic) products and talk about their favorites. Mother Natch dismisses a concealer called Trump-a-licious that “it goes on really orange” and “is just kind of trash,” while a cooling mist for her recent “hot flashes” has a secret ingredient of “actually giving a shit about our climate” (@pattiegonia, October 30, 2020). A lipstick called Democracy is the real winner of Mother Natch’s haul, because “it looks good on everybody,” says Pattie, as she scrawls VOTE on her forearm (@pattiegonia, October 30, 2020). The video is meant to remind people to vote (“gag me, Daddy Biden,” Mother Natch squeals), but it takes as its subject a deeply serious topic—threats to American democracy and an ever-heating planet/Mother Natch—and by situating her joyous “gay screaming” alongside thinly veiled critiques of Trump’s antienvironmental agenda, Pattie crafts a message that is simultaneously accessible and thoughtful, sober and merry (@pattiegonia, October 30, 2020). But Pattie as Mother Natch is also deeply ironic and sincere. “Maybe if it was called FATHER NATURE, you’d give a shit” is scrolled on a protest sign held up by Wyn (@pattiegonia, September 30, 2019).

Pattie uses the Mother Natch persona to instill authority and antagonism into her environmental message. If we can imagine nature as “no longer a repository of stasis and essentialism, no longer the mirror image of culture,” as Stacy Alaimo (2000) argues, feminist reconsiderations of nature will “neither seek an untainted, utterly female space outside of culture nor cast off bodies, matter, and nature as that which is forever debased” (10). Alaimo addresses the paradox of considering nature as “both an empty space and a field replete with cultural values” by saying “movement” within these possibilities makes feminist recasting possible (17). Making Mother Nature not only corporeal but also a drag queen is a deeply queer environmental performance. As ecofeminists and others have long pointed out, when the patriarchy links the natural world to femininity, it is inherently exploitative. But Pattie invokes the trope not only to lend a familiar note to the iconography she is using but also to turn Mother Natch—Pattie’s personification of Mother Nature—from a submissive and exploitable object to an agential and angry force. Pattie undoes the cultural mythology of a feminized (and thus passive and exploitable) nature by recasting her as vivacious, opinionated, and confrontational woman. It is a reminder that as a cultural myth, Mother Nature represents systems and forces that have limits.

One of Pattie’s most elaborate ecojustice drag projects occurred in November 2019. She released a spoken-word music video, a collaboration with REI, @sustainablecoastlinehawaii, and @debrisresearch, entitled “Everything to Lose.” The video, which was later chosen for Sundance, now has more than 1.4 million views on YouTube and features Pattie in gowns designed by @adiffnyc, a sustainable clothing company based in New York City that employs refugees. Pattie’s “narrator dress” was made from plastic bags and her “protagonist dress” from upcycled chiffon and love letters to Mother Nature collected from community members and read out loud by various people in a cutaway montage. Against the ticking of a clock, Pattie proclaims: “Our mother is dying while we are out living/We must turn the tide from taking to giving/We will make a difference if we dare choose/It’s time that we act…./we’ve got everything to lose.” The visual messaging of the video involves Pattie as ethereal sea creature, writhing in plastic discarded in the waves, lying among piles of plastic refuse on the beach, and emerging from the ocean weighed down by plastic netting (figure 6).

The final minute of the video, accompanied by a ticking clock and the repetition of “What we will have left is what we have done,” sees Pattie strutting down the beach to join a line of people standing hand in hand. Gendering nature as female, Pattie notes that “Mother Natch is hella pissed” because “a woman knows when she’s been told/When the men in the boardroom think she’s being too bold/Too proud, too outspoken, too much to handle/when she’s been made the doormat instead of the mantle” (REI Presents: Everything to Lose by Pattie Gonia 2019). Sexism is just as much to blame for climate change as the exploitation of natural resources. As Noël Sturgeon (2009) makes clear, nature is “a legitimating idea” that gets used to lend power to oppressive systems, including homophobia. Deeming something “natural” means it adheres to “truth, inevitability, and immutability, beyond the reach of social criticism or democratic dialogue” (19). Work has to be done to create a “liberatory possibility in strategically arguing from nature against social norms” since norms and “nature” often get attached to each other (21). For these reasons, Pattie refuses to shy away from the associations between the environment and the maternal woman as a way to multiply the representations of gender in nature. There is nothing natural about the exploitation and abuse of natural resources or the accelerating climate emergency, Mother Natch makes clear, and many of those consequences are a direct result of restrictive and destructive representations of gender. In her final reversal of the narrative about human dominance over nature, Pattie/Mother Natch explains that “what will be left is what we have done,” but humankind has the power to choose a different path (REI Presents: Everything to Lose by Pattie Gonia 2019). Combining images of Wyn (with little makeup and no wig) in a high-fashion trash dress and floating in a sea of plastic as a furious and aggressive Mother Natch, the video recasts nature as gender fluid and able to speak. And she is fed up.

While Pattie qualifies as an “influencer” based on her followers, she does not self-identify as one and is very forthcoming when engaging with sponcon, or sponsored content.

A “vigilante” Instagram account called @publiclandshateyou has no qualms about overtly calling out users who bring potential harm to outdoor spaces. Their bio notes, “People ‘doing it for the gram’ are prioritizing profit, fame, and ‘rad pics’ over the health and future of your public lands. Who else is fed up?” The account pointedly adds an eighth principle to Leave No Trace’s list of seven: “Share Responsibly,” which encourages users to ask themselves What, Why, and Where before sharing on Instagram. Highlighting the dangers of geotagging a location, a post from September 25, 2019, explains, leads @publiclandshateyou to ask: “[W]hy would you give the exact location of an environmentally sensitive area to someone who may not have the necessary experience or knowledge to safely visit that area and treat it with care and respect?”

See also Sarah Jaquette Ray’s “Risking Bodies in the Wild,” which traces how currents in risk and adventure cultures replicate historical narratives of racism, sexism, and classism. She calls on environmentalism “to incorporate an array of corporeal interactions with the physical world, but its failure to do so thus far points to its hidden attachment to the abled body” (2017, 33).

See also Peter Boag, Same-Sex Affairs: Constructing and Controlling Homosexuality in the Pacific Northwest (2003), C. Packard’s Queer Cowboys: And Other Erotic Male Friendships in Nineteenth-Century America (2005), and Will Fellows’s Farm Boys: Lives of Gay Men in the Rural Midwest (2001). I would even reference Tom of Finland’s famously erotic beefcake drawings of “rugged” and hypermasculine gay men among these histories. His work was influential in the mid-twentieth century for representing gay men as muscular and as working in various working-class occupations (like loggers and military men) considered anything but impotent and effete.