Alejandro González Iñárritu’s frontier adventure drama The Revenant (2015), shot in Alberta, Canada, may seem, at first glance, to offer all manner of immersive qualities and ideo-affective potential on which environmental thought and advocacy might draw. Its wide release and box-office success have made it an ostensibly known entity, ideal for introducing viewing publics to lesser-known forms of ecocriticism. Its vividly rendered images of mountains and river valleys—locations shot in natural light by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki—make all the usual appeals to the humbling sublimity of wilderness, while its story worries over an emerging nineteenth-century capitalism that is gathering its early energies. What’s not to ecocinematically like?

The problem is that the film text, its promotional attachments, and much of its critical reception have functioned to obscure the ecological states of The Revenant’s primary shooting locations in western Canada. This maneuver is part of the film’s wider, gendered, and mediatic effacement of its own material enmeshments in the world. Its masculinist, retrograde narrative is an obstacle to progressive ecocritical readings that seek new understanding of environment, of humans as environmental beings, and of cinema as a medium capable of drawing forth environmental identifications from audiences sufficient to help effect systems change. The Revenant is understood in this analysis as a composite that includes frame contents, promotional rhetoric, and critical reviews—that is, as an aggregate of the media flows that emerged between 2014 and 2018 to form a heterogeneous media event running from the prerelease promotional phase through the theatrical release window and then through a two-year period of critical reception. The film event channeled to spectacular effect the affective, semiotic, audiovisual force of “extreme” and “wild” environments while ignoring the complex, inter-constitutive relations between human beings and their environments. The film acted in and upon its shooting locations, in the agentic and specifically theatrical sense of that verb, without ever being there in terms of biopolitical risk and mindful ecological presence.

Instead, this commercial production performed a semiotic resource extraction exercise at location shoots, gathering raw audiovisual material for processing and sale elsewhere in a recognizable product form—the male adventure narrative. Its relentless, cross-platform promotional campaign pushed audiences away from a possible meditation on the imaged air, waters, and lands and toward the masculinist, competitive adventures of its director, star, and crew in winter conditions. The gender implications of this become clear when considered alongside its retrograde view of nature as red in tooth and claw, a nature that is mere crucible for the teleologies of industrializing man. After the film’s star, Leonardo DiCaprio, won his long-sought-after Oscar for best male actor (Iñárritu repeated as best director, and Lubezki won for cinematography), all three men went on to other projects, likely unaware of Victor Seidler’s insight that “masculinity is only as secure as your last competitive achievement. This fear of what nature might reveal is an endemic aspect of dominant forms of masculinity. It is built upon a denial of what cannot be denied, since it remains part of us” (Seidler 1994, 18). The Revenant, left on its own terms, trades potential insights into the co-constitutive relations between humans and environment for the same gendered and individualist metaphysics that has undergirded a long history of commercial-industrial production. Fortunately, ecocritical examination can render this studio product a symptom of the problem rather than an unchecked agent of it.

The Revenant’s Gendered Media Ecology

From an ecocritical perspective that affords a wider view of media ecology beyond the contents of the film frame, The Revenant involves much more than a loosely biographical revenge tragedy about Hugh Glass, a nineteenth-century trapper bent on avenging the murders of his Pawnee wife and son. The film’s materially facilitated semiotic registers originally emerged in the context of a multiplatform and multifaceted media event. That is why I adapt the term “multiplex” to my critical purposes here, a word denoting multiple elements in complex relation; a signal able to carry numerous messages; and a cinematic venue with more than one screen. I refer to the film and its promotions, as well as the homologous and ideologically favorable critical reception that preceded, accompanied, and followed its release, collectively as its multiplex. The film text and its promotions combined to create a range of meanings set within the “growing trend among consumers to serially consume small, incomplete ‘chunks’ of multiple media types—television, radio, Internet, and print—within a short time period” (Lin, Venkataraman, and Jap 2013, 310). The argument then mingles features of the film’s masculinist story and often fawning promotional rhetoric with environmental conditions and politics at the film’s primary shooting locations in Alberta.

The analysis does not take up these three aspects in strictly linear fashion because it accords with Karen Barad’s relational ontology, as outlined in her book Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (2007). Barad’s notion of intra-action assumes that things and processes do not preexist before they mingle with other things and processes. They are always already in states of intra-active becoming. For critique to trace relations, it must be willing to jump around to avoid being about “subtraction, distancing and othering,” as Barad puts it in a short critique of critique itself (Barad 2009, para. 4). Barad’s suspicion of binarily constituted individualism stands opposite The Revenant’s celebration of the same and its implicit claims that human actions play the lead role in any biospheric drama that matters. The Revenant privileges human agency and thus cannot help but distance and “other” the environment. My analysis construes the film as a missed opportunity to explore the woven states of thought and matter in a time of environmental crisis, where cinema could ideally exhibit a “knowing [that] is a direct material engagement, a cutting together-apart, where cuts do violence but also open up and rework…agential conditions of possibility” (Barad 2007). This knowing could cinematically render the states and agencies of nonhuman entities coeval to the human, rather than subordinate.

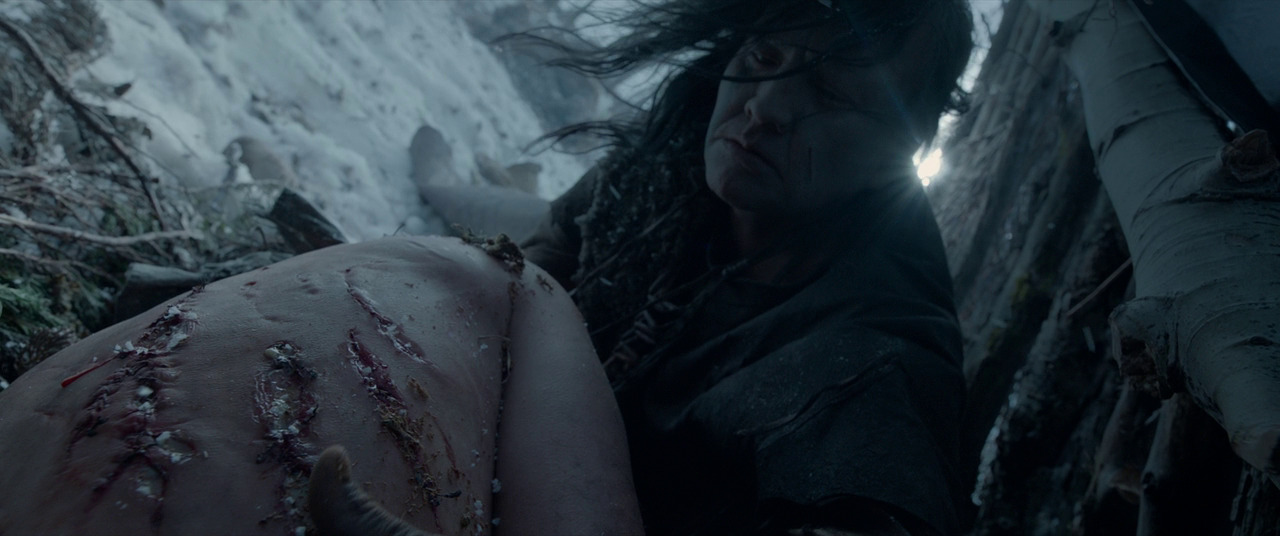

In order to approach The Revenant’s gendered cultural weave, this analysis draws on Finton Walsh’s conceptualization of the performance of male crisis (2010), which Walsh says involves tropes of self-sacrifice, subjection, abjection, wounded states, fragilization, violence as solution, and heroism as compulsory. I direct portions of Walsh’s primarily psychological analysis toward The Revenant’s dramatically documented production activities at its shooting locations; its strategic embrace of cinematic melodrama; its staged crises of bodily condition in winter environments; and its tonal register of nostalgia. My aim is to identify a theatricalized (and performative, in the Butlerian sense) ecomasculinity that is more affected than affective as it camouflages its role in the industrial compromise of environments.

New Regency Productions, 20th Century Fox, and a wide network of entertainment outlets devoted to public relations and reviewing coauthored Iñárritu’s theater of male duress by helping to circulate what Timothy Morton describes (when referring to a strain of American ecocriticism) as “masculinity memes, including rugged individualism, a phallic authoritarian sublime, and an allergy to femininity in all its forms” (Morton 2010, 274). This audiovisual array of spectacular and gendered exertions (and the breathless reporting on them) worked to obscure and discursively limit a rich and complex geography of western Canada, where most of the film was shot, a region currently facing a range of ecopolitical stressors. My emphasis on the film’s multiplex is useful for explaining how its gendered discursive messaging works to conceal the material dynamics of media apparatuses and of imaged lands. It will become clear how the vulnerable and traumatized ecoheroic body of Leonardo DiCaprio as Hugh Glass, and the adventurist tales of hardship purportedly suffered by crews on location shoots, overwrites what Stacy Alaimo explains is “the carbon footprint of gender” (2009, 1). She describes a more genuine form of bodily vulnerability that is seen when environmental protestors gather naked, citing the example of Spencer Tunick’s photographing of hundreds of people on Switzerland’s Aletsch glacier: “They perform vulnerability as a trans-corporeal condition, in which the material interchanges between human bodies, geographical places, and vast networks of power provoke ethical and political actions” (2009, 3). This nakedness, powerful in its ecotheoretical implications, differs markedly from scenes in which The Revenant’s costume designer Jacqueline West ensured that either dry suits or electrically heated padding fit snugly beneath the wet wardrobe worn by the actors.

At its core, The Revenant reinscribes the once uncontested, regulatory, and self-celebrating masculinist narratives that once suffused entire genres of film. When these narratives re-present themselves today, at a time when such encoded structures of domination provide as much enabling energy to industrial consumerism as fossil fuels, certain ecomasculinities can be seen as reaffirming values that bundle “nature” and the “feminine” into a kind of discursive monism, an imagined cultural zone that is a proving ground for the testing and triumph of male agency. Such ersatz dilemmas contemporize the retrograde, benefiting the agents in whose interests ecomasculine “crises” act. Hugh Glass is left by his companions to die following a bear attack, and because he survives to take his revenge, the film dubs him a “revenant,” one who returns from the dead. But resurrected with him in the film’s multiplex are the hallmarks of masculinist wilderness narratives that carry their usual valuations. At a time when Mount Everest is littered by the frozen bodies of ill-trained would-be adventurers; when wealthy, conservative hunters goad animal welfare advocates with widely circulated pictures of trophy kills; and when global “tourism’s overall resource consumption may grow by between 92% (water) and 189% (land use) in the period 2010–2050” (Gössling and Peeters 2015, 639), Iñárritu’s comparing of his production shoot activities (described in a section below) with the Arctic explorations of Ernest Shackleton extends beyond the melodramatic to the tragicomic.

The heroic mode of such a production shoot narrative may be readily apparent to ecocritics but is less apparent to general viewing publics. Masculinist tales of conquest over states of nature have long carried a normative force engineered by all the usual dualist perspectives that set culture opposite nature, inaugurate unsustainable practices, and service the false impression that there is any such place as “away,” ecologically speaking. This film provides extraordinary cover for such perspectives (that hide in plain sight) because cinema’s most powerful illusion involves its seeming ethereality as a medium. It creates the impression that it is a supramaterial, representational space to which worldly phenomena somehow “go” to be transmogrified into signs that carry no material effects, only cultural ones. But phenomena (including cinema itself) are, of course, never materially away. An instance of cinema is not even a discrete entity, because its multiple material residences are far too distributed for that to be the case. Film manifests in different places and ways, emerging sensually in light and sound waves, hibernating in electromagnetic disc storage, or lingering on as either e-waste or a sense impression nested in a material substrate of consciousness. But an emergent sense of exactly where cinema may be said to materially exist is eclipsed by the ostensible filmic solidities attested to by the audiovisual record of the profilmic. This is how masculinist adventure narratives are able to present their gendered and industrial conceptions of environment as seemingly self-evident in terms of their assumptions while the material-discursive effects of multiplexes remain largely out of view.

Cinema does not, in any sense, exist independently of the material, mediatic networks that channel it—these networks are cinema. That cinema has some preexistent, phantom form or ontology involves the same misapprehension that director Iñárritu and the studio’s public relations team perpetuated when they described the film’s stars and crew as being able to get away from culture and closer to a state of nature for purposes of filming. In actuality, the crew was nature, bio-entities merely transiting to a different node in the North American ecological networks that sustain them. But that sense of humans-in-world and world-in-humans is not an easy sell compared to the familiar nature/culture dualism that structures so many dramatic arcs in the Western imagination, stories that, in their material-symbolic form, are extensions of Western philosophical precepts that have

enabled and rationalized the expansion of human ambitions, creating incredible monuments to civilization, ego, and white male pride; and while it generated unimaginable wealth for those lucky enough to be born into the right demographic, in the right country, in the right epoch, it also established and then accelerated all the conditions associated with catastrophic climate change. (Dufresne 2021, para. 36)

The cinematic vistas of The Revenant invoke the ecological but perform a type of transmissive-philosophical work that, like all media communications, “inadvertently communicate[s] our dismissive relation to the humans and natural environments who pay the terrible price for [media] efficiency, even for its poetry” (Cubitt 2017, 6). The Revenant’s visual poetry upon the film’s release was synchromeshed with the blunt and efficient messaging of its promotional attachments, which called forth the hyperrealities of infotainment journalism to reinforce the philosophical programming that has helped land the West in the Anthropocene.

“Buzz,” a term once understood as the “sibilant hum, such as is made by bees, flies, and other winged insects” (OED Online 2020), now describes the mutually reinforcing messaging that arises between media platforms, a phenomenon well explained by media multiplexity theory (see Ledbetter and Mazer 2013). The result is a nimbus of seeming authenticity for a multifaceted set of media events. The goal is to suggest that a piece of cinema has innocently emerged on the cultural field, an appeal to humans’ “latent belief in the spontaneity of nature” (Bergson, in Bennett 2009). The event is taken up by press feigning credulity, apparently eager to explore this arrival with audiences in good faith, as if, in the case of The Revenant, the filmmakers somehow communed with nature before returning to culture from harsh conditions to unveil a film as if it were a moon rock, its aura deserving of awe and its appearance clearly worth the difficult and selfless effort. In actuality, The Revenant’s multiplex media platforms came courtesy of device manufacturing, infrastructural network builds, energy draws and emissions counts, while its messaging redirected human curiosity about nature toward narrow and coded criteria for commercial achievement, which the film set itself up to easily fulfill. Its engineered success worked to reinvigorate the gendered and anthropocentric subtexts of the male adventure narrative, failing to author new eco-insights that would render such exploits misadventure and instead attune viewers of cinematic vistas to new ways of seeing and being.

If The Revenant’s multiplex could succeed in representing the director, star, and crew as emerging triumphantly from the wilds after suffering the ravages of nature, as Hugh Glass himself suffered for his trade two centuries earlier, then the filmmakers could appear to have earned their commercial success, just as early settler culture emerged from nineteenth-century frontier hardships into twentieth-century industrialized comforts. Both the film text and the cultural performance of “endurance filmmaking” (Kay 2015, para. 1), as one critic was only too willing to call it, rely on naive conceptions of nonhuman spaces and species. They insist nostalgically “with exceptional anthropocentric rigour, [that] human concerns can find elemental expression when profilmic locations and digitalized renderings of same reflect, echo, confirm, and celebrate human agency” (Trono 2019, 64), that being what wilds are ultimately for, which is playing a supporting role in the performance of, in this case, a besieged male subject whose struggle against the elements encodes a deeper struggle for recognition and preeminence in the mnemic systems of gender regimes. That is the rhetorical aim behind the melodramatic tales of production shoot exigencies involving low temperatures, locational isolation, snowy terrain, narrow “magic hour” shooting schedules, and method acting—to engender sympathy.

The Revenant retains an unusually stubborn fidelity to traditional conceptions of human and nonhuman being and, by implication, of matter itself. Nina Lykke usefully reminds us that

Matter does not serve as a mere support for discourse, nor is it merely the end product of human-based citational practices. Rather, discursive practices are specific material configurations/(re)configurings of the world…. (2010, 173)

Obviously, cinematic and commercial languages that codify environments in routine ways will carry far more sway with publics than agential realist accounts of matter such as Barad’s. So, we need to ask with Barad, “How did [film] language come to be more trustworthy than matter? Why are language and culture granted their own agency and historicity while matter is figured as passive and immutable, or at best inherits a potential for change derivatively from language and culture?” (2003, 801) Barad and others know that answers can follow from, as Stacy Alaimo puts it, “attending to the material interconnections between the human and the more-than-human world” to draw out the feminist “ethics lurking in an idiosyncratic definition of matter” (2010, 2). The failing of The Revenant is that its makers did not know what they really had to work with, in the natural light of the Rocky Mountain day, which was the extraordinary, intra-active and agential relations between culture and environment, domains thought distinct prior to new materialist efforts to grant matter its own ontologies, beyond those assigned to it by culture. The filmmakers retreated instead into wilderness adventure tropes and a shooting location not far, ironically, from where Frank Borzage shot his 1922 melodrama The Valley of the Silent Men. In the sections that follow here, the methodology brings into relation the film’s multiplex, the gendered elements of its narrative text, and the environmental conditions at several shooting locations where I undertook field research in the late winter of 2019. It is hoped that this problematic—which resists any separating out of promotions, frame contents, and site dynamics—exemplifies a type of synthesis that grounds moving image production environmentally, by emulating ecocritically the all-at-onceness of environmental dynamics themselves.

Men and the Multiplex Go to the Mountains

Iñárritu refused to chroma-key The Revenant, relying instead on a high number of exterior-shot scenes filmed in western Canada’s Kananaskis Country. This area comprises a system of parks and protected areas located in the southwest quadrant of the province of Alberta in the front ranges of the Canadian Rockies. It is a rain-shadow zone where the foothills and river valleys of the Bow corridor and Dead Man’s Flats host cold and snowy winters, but usually experience warm weather chinooks before spring thaws bring high water. Moderate summers follow. A little farther east stands Fortress Mountain, where major portions of the film were shot, and east sits Mini’Thni, a First Nations Stoney reserve and battle scene location. Beyond Kananaskis are the Alberta Badlands near Drumheller, where a stunning shot was taken of Tom Hardy in the role of Fitzgerald, facing a river and coulees with open sky beyond as he watches a meteor transit the sky. The bear attack scene, where Glass is almost killed, was shot outside the province in Squamish, British Columbia, in the old-growth-timber Derringer Forest, and when warm weather conditions arose in Alberta, leaving snow levels low, some scenes were shot in the Tierra del Fuego region of southern Argentina. But the majority of scenes were shot in Alberta: the Fortress Mountain region, Elbow River Canyon, Abraham Lake, and King Creek (Mounsey 2022).

Several of these areas constitute the region’s “water towers,” which are glacier melt systems vital to lowland agriculture. Many of these areas are only a few hours’ drive away from the corporate office towers in Calgary that operationally drive the vast Alberta oil sands, one of the largest industrial undertakings in the world. Farther north, near the town of Fort McMurray, are the sands, areas where bitumen is mined from vast pits that are dug following removal of boreal forest. The extraction process creates toxic tailings ponds that, if not remediated (a difficult, expensive process), can compromise streams, lakes, and groundwater. The process also requires vast amounts of water from the Athabasca River, which, if the draw is unregulated, could lose its ability to ecologically support downstream areas. Oil sands operations burn fossil fuels to produce fossil fuels. At the time of the release of The Revenant in 2015, North American pipeline politics were no less complicated than they are today, with changing federal and provincial regulatory processes in Canada (federal and state in the United States) being constantly challenged or reinforced, depending on the political orientations of governments of the day. When “climate warming, via its effects on glaciers, snowpacks, and evaporation, will combine with cyclic drought and rapidly increasing human activity in the WPP [Western prairie provinces] to cause a crisis in water quantity and quality with far-reaching implications” (Schindler and Donahue 2006, 1), pipelines and the petro-agencies behind them will be partly to blame.

Alberta’s geography has a history with Hollywood. The province has been a location of choice for American filmmakers for over a century, with stories set or shot (or both) in areas ranging from its northern boreal forests to its southern desert regions, and from its Rocky Mountains to its expanses of prairie. Filmmakers concerned about the environmental effects of the oil sands have undertaken high-profile visits to the area and made public statements following them. In 2010, Canadian-born James Cameron did a three-day tour of the oil industry with its representatives and met with the provincial premier, leaders of opposition parties, First Nations groups, and several academics. Avatar, of course, provided a storybook allegory of the cultural dangers of corporate-state-military alliances to facilitate resource extraction at the expense of Indigenous peoples; the downsides of its multiplex’s material effects have also been noted (see Trono 2019). This was the region into which the filmmakers came, with DiCaprio aware enough of the biopolitical stressors in the area that he focused some of his environmental advocacy efforts there, even as he agreed to star in a one-dimensional adventure narrative about a trapper tormented by the wilds and living only for revenge.

DiCaprio’s advocacy efforts drew fire after the release of The Revenant when the actor commented in interviews on the initially cold and then suddenly warm temperatures the crew experienced during shooting at Fortress Mountain. The change of weather forced the production to relocate to southern Argentina. In Variety, DiCaprio was reported as saying,

I’ve never experienced something so firsthand that was so dramatic. You see the fragility of nature and how easily things can be completely transformed with just a few degrees difference. It’s terrifying, and it’s what people are talking about all over the world. And it’s simply just going to get worse. (Nerman 2015, 5)

The winter of 2015 was one of the warmest on record in Alberta (CBC News 2016). But the winter shoot was compromised specifically by a predictable weather event in Alberta, the warm-weather chinooks that are common at that time of year. DiCaprio did not make clear in his public comments whether he had meant that warmer weather due to climate change had been compounded by the chinook, so he was immediately pilloried by many North American news agencies and oil and gas advocates as purveying a naive, celebrity environmentalism.

His reputation took a second hit when it became known that “[w]hat DiCaprio didn’t share with his followers was that he had rented a house outside of Calgary from an oil patch executive and…was flying on a private jet between Calgary and Los Angeles every weekend” (Yedlin 2019, 201) DiCaprio’s extensive use of private jets was also raised, a legitimate observation given that a study published in Nature Energy shows that wealthier individuals spend the most on transportation, a consumer category known for its heavy energy draw (see Oswald, Owen, and Steinberger 2020). Blowback worsened when many recalled that in 2014, DiCaprio had rented a superyacht from Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, whose family fortune is based heavily on oil wealth. There is a scene in The Revenant where Hugh Glass has a riding accident and requires warmth to survive while injured at the base of a cliff. He guts his dead horse to crawl inside the carcass to avoid freezing and emerges the following morning amid springlike conditions, gazing up at trees dripping with meltwater and glistening with sunlight. As happens sometimes when watching films featuring famous actors, it is difficult to suspend disbelief and see only Hugh Glass in the scene, once climate issues are taken into consideration. We see DiCaprio as simply another interpreter of unusual environmental conditions—which could be productive if the character were more like a protagonist in a Kelly Reichardt film and less like Hergé’s Tintin or Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo.

The film manages to incorporate, in this single scene, all seven of the features Finton Walsh (2010) identifies with the performance of masculine crisis. DiCaprio/Glass is self-sacrificial in his overall efforts to avenge his wife and son, efforts that, in this scene, land him injured at the base of the cliff. Nature is the crucible that would see his male subjecthood dissolved into feminine nature where his wife dwells, there to be reunited, which is what essentially happens in the final frames of the film. But he does not yet transcend; instead he experiences the subjection demanded by the performance script:

every time transcendence falls back into immanence, stagnation, there is a degradation of existence into the “en-soi”—the brutish life of subjection to given conditions—and liberty into constraint and contingence. This downfall represents a moral fault if the subject consents to it; if it is inflicted upon him, it spells frustration and oppression. In both cases it is an absolute evil. (Beauvoir 1974, xxviii-xxix)

Abjection engulfs DiCaprio/Glass as he spends the night in the bowels of the horse and struggles out of its midsection the following day, symbolically invoking the mother’s body as the perennial site of abjection and acting as both a precondition for and threat to male subjectivity. Faced with difficulty shoring up the boundaries of the male self in the feminized wilds, violence as solution asserts itself through the crisis actor as he continues to pursue revenge the moment he exits the horse carcass. This decision leads to yet more wounded states and enhanced fragilization, all the while attempting to call forth the usual masculine identifications that accept heroism as compulsory.

Walsh explains that certain types of male performativity “infer that there are active agents of crisis, and agents in whose interests crisis acts” (2010, 1). Men who directly perpetuate gender inequality fall into the former category. The latter, meanwhile, involves agents who want to flip the persecutorial script to suggest that struggles for gender equality have reversely discriminated against men, supposedly leaving men’s identities in triage following “decades of gay, lesbian, and feminist insurgence, and concomitant changes in the labour orders” (2010, 3). This imagined plight is neither homologous with, nor affectively comparable to, gender subordination as it has been experienced by women and nonbinary persons since antiquity. But it would constitute a secondary crisis for gender regime marginals were recent gains erased by men who, as John Waters worryingly hopes, will “finally start to stand up for themselves…to confront the sources of the propaganda which makes possible their marginalization from home, family, and society, to challenge the bully-boys and bully-girls, the misandrists and the feminazis” (quoted in Walsh 2010, 3–4). Such a militant social script has a subtler variant of the reassertion of dominion. It involves an appeal to the culture at large that men should be preeminent on the cultural field due to their sacrifices and suffering, and there is no better ground for such suffering in the adventurist imagination than persecutorial Nature Herself. When asked about the level of violence and suffering in The Revenant, Iñárritu replied, “there is no gratuitous violence. These guys were eating animals, wearing animals; they were threatened by accidents, diseases, tribes, wars. This is the real world. This isn’t pasteurized” (Segal 2015, para. 13). But why was 2015 a time for a story about the difficulties of frontier life, from what is largely a male, settler perspective? Why were the serial, violent episodes multiplied and exaggerated beyond what would most likely have been the norm? Why ask viewers to suture their identifications to a protagonist who was part of a westward expansion bent on suborning lands and peoples to violent ecosocial controls (however much said character may have intended things to work out well for his Pawnee wife and son)? Why, when even the film’s star is preoccupied by climate science debates and environmental slow violence, does The Revenant’s multiplex insist that viewers’ primary response should be to marvel at the intensity of suffering in the wilds faced by men struggling for environmental and social sovereignty? And why characterize a well-funded location shoot that had all the amenities as presenting hardship?

Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight, which was released the same year as The Revenant, featured its own set of elaborated corporal punishments and was also filmed in a wilderness location upon equally insufficient snowpacks, to the regret of producer Harvey Weinstein, who also suggested that he had suffered in a struggle against capricious Nature: “Would you like to be in the movie business? Would you like to go to a place where it’s always snowed and it doesn’t, where all of a sudden in the middle of winter it gets hot?” (Tapley 2015, para. 2). Both films’ elaborated dramas, on- and off-screen, land squarely in the territory of melodrama, a “genre whose very nature involves a subject exceeding its treatment, a genre of excess” (Henke 1995, para. 11). But for what, exactly, do characters in either of the two films suffer? No answer comes from thinking on the respective scripts. They do not speculate on the depravity of human beings, the eruptive powers of hindbrains, or the existential aporias of the human condition. Neither film reads as philosophic, deterministic, or nihilistic in those ways. They are odd pantomimes of bodily crises experienced in harsh environments, enacted predicaments that follow through on a punishing formula wherein violent acts must balance out, even when there is no internal filmic reason for this necessity. It is as if the films’ masculinist acts were directed toward righting some sort of external wrong, out on the cultural field where the films circulate, and the reason for this rhetoric of suffering may be understood through ecofeminist critique.

Such violent, cinematic crises have a traceable history in American film and literature. We see that “contemporary films revisit and re-work themes familiar to us from earlier cinematic eras (most particularly in the context of film noir), and in so doing, they draw attention to the historically shifting fragile underpinnings of masculinity and its cultural articulations” (Bainbridge and Yates 2005, para. 26). The ne plus ultra of contemporary masculinist, cinematic suffering is Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004), which, along with several of his other films, carries a gendered subtext:

[t]he persistent image of heroic male bodies bruised, beaten, and displayed for the film audience challenges the gendered binaries that have characterized such moments of powerlessness as feminine. The excessive physical tortures illustrate the importance of suffering as an essentially masculinist trait. (Brown 2002, 1)

When Hugh Glass suffers in The Revenant, it is an empowering disempowerment. The film effectively mounts an apologia for the logic of gendered domination of environment, as both Glass and the westward expansion of industry he represents writhe dramatically while penetrating a wilderness saturated by water in all its states and consistently limned as yonic.

Despite the fact that the production had to flee Alberta’s warm late-winter weather in search of greater snowpacks, Iñárritu worked tirelessly during postrelease media interviews to create the impression that the shoot constituted a heroic undertaking, given the punishing force of the Canadian winter:

There was something very positive about shooting in those conditions, to understand what those guys [from the 1820s] went through….We don’t have adventures anymore. Now people say, ‘I went to India … it’s an adventure.’ No: We have GPS, a phone, nobody gets lost. Those guys really were in a huge physical, emotional adventure in the unknown territory. After you see what these guys went through, you understand what pussies we are: Our apartment is not at the right temperature, there is no ham in the fridge, and the water is a little cold … When did that happen? Actors were not in sets with green screens and laughing….They were miserable! And they really feel the fucking cold in their ass! They were not acting at all! (Jagernauth 2015, para. 6)

The performance here involves evincing sympathy for other men in crisis and for a bygone age of geographical exploits. Trappers such as Glass are “guys” compared to which anyone unwilling to experience the elements like those men did are “pussies.” The actors in his view require the intrusive anality of “cold in their ass” in order to commune across space and time with those who faced frontier realities. But the location shoot was exactly like the technologically equipped trips to India that Iñárritu derides. Heated and well-appointed trailers were always nearby. After shooting each day, the crew would enjoy restaurants in the nearby city of Calgary (an hour’s drive away) that featured fusion cuisine with staples like Angus beef and arctic char. After a few months, the whole crew returned to urban comfort, from what one critic inexplicably called “Upper Canada,” an area only four hours from the US border by car. Another reviewer writes, “There is an odd poetry about a survival drama struggling to find its way to completion, but it would seem foolish to bet on anything but Iñárritu seeing the job through in spectacular style” (Jagernauth 2015, para. 8). The multiplex is not equipped to perceive that the only “odd poetry” of such performed crises of male bodies in environment, on- and off-screen, comes from the unexpected interventions in human discourses of the nonhuman agencies of various assemblages of matter: patterns of trees deemed unsatisfactory for backgrounds in some scenes, condensation gathering on camera lenses, or the sudden arrival of warm temperatures due to chinooks. Absent from the film is any treatment of the contemporary and “blasphemous idea that nonhumans—trash, bacteria, stem cells, food, metal, technologies, weather—are actants more than objects” (Bennett 2010, 115), actants equivalent to and intra-active with social bodies.

The promotion and reception aspects of The Revenant’s multiplex severely limited the extent to which audiences could interpret the rich cinematography for themselves. Finding viewers who experienced the film with no advance knowledge of pre- and postrelease buzz is akin to finding jury members with no prior media-borne knowledge of a famous criminal case they are asked to adjudicate. One avid blogger wrote, “Even though the Oscars are still two months away Leonardo DiCaprio has already been getting buzz about his performance. So far, he is the favourite to win Best Actor. I was very anxious and excited to watch The Revenant and see what all the fuss was about” (Mink 2020, para. 4). A global media company like Forbes knows how to identify a winning marketing campaign for a media event. It says of The Revenant that

audiences, just like Academy voters, are attracted by the premise of how difficult a movie is to film. To the Academy, it’s a mark of how dedicated a director is to their craft, proof that they went above and beyond the norm in the care and skill with which they brought their vision to life. But to audiences, it’s the curiosity gap that will lure them into theaters. (Grauso 2015, para. 7)

Other entertainment journalists also took up the multiplex’s proffered claim that suffering in the film was cinematically realized through the ordeal of endurance filmmaking: “Both the storyline of Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s The Revenant and the story of its production are imbued with a ferocious will to live” (Kay 2015, para. 1). In this critic’s interview with Iñárritu, the director compares his exploits to those of Ernest Shackleton, one of the key figures in what has been called the heroic age of Antarctic exploration. He claims,

When [Ernest] Shackleton went to the end of the world he would recruit people and he would never lie about it. He said, ‘It will be cold and probably we will not return.’ Everybody who was hired [for The Revenant] knew it would be an extremely challenging shoot and the standards I set were very high. The first guy that did those things was myself…..There was a lot of camaraderie and happiness. (Kay 2015, para. 24)

Iñárritu echoes Stephen Crane’s deterministic view of nature and sense of fraternal consolation for nature’s cruelty as expressed in “The Open Boat,” a story of men stranded on the open ocean: “It would be difficult to describe the secure bond between men that was here established on the seas….they were friends—friends in a more strangely iron-bound strength than may be ordinary” (1898, 16). Iñárritu also plays on language from the likely apocryphal story that claims Shackleton solicited men for his 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition with the following advertisement: “Men Wanted for Hazardous Journey. Small Wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.” (Time 2003, para. 1). The director ends by saying, “As a film-maker, I’ve always wanted to do a film in landscapes. Directors I admire have done that, but I’ve never explored it” (Kay 2015, para. 4). But descriptions of the location shoot are not in keeping with a sense of creative exploration of environment where process is opened up to the ecological lays of the land, and where forays into land- and waterscapes by the patrilineal, directorial, and commercial hallmarks that structure masculinist crisis are absent altogether.

These hallmarks include star prominence in framing; a linguistically silent protagonist; a soundtrack of plosive, guttural grunts and gasps; editing paces frenetic and reward-driven enough to initiate dopamine release; and a diegesis of dire circumstance where bodily harms are deemed sufficient to secure empathetic identification from audiences. Glass is shot at, shot at when underwater, nearly pierced by arrows, nearly drowned in torrents, beaten, stabbed, driven off a cliff, and mauled by a bear. One critic refers to this kinetic arc by observing how “Lubezki’s roving camera captures the majesty and indiscriminate fury of nature and does not let up throughout the film” (Kay 2015, para. 13). Nature is only seemingly indiscriminate or furious in terms of its effects on humans from the perspective of people unwilling to think about the multiple agencies that inhere in any ecology. Within the film text, culpability for Glass’s outrageous fortunes rests with nature while the altogether unlikely and unnatural pace of events accords with American cinema’s 120-year march toward near global dominance in the development of hyperkinetic editing. Slower-paced scenes do appear in the film but for relatively brief lyrical effect, not as an expression of, say, the insight that different assemblages of matter experience time differently. These scenes most often appear at points where Glass thinks of his murdered family, and this is where the film features a surprisingly retrograde alignment of Glass’s Pawnee wife with air and water states silently rendered. She has no voice in the one flashback sequence when she is still alive, after which she appears as either a supernatural phantom or a presence imagined by Glass. The film does not so much fail the Bechdel test in such moments as it removes cinematic grounds for women’s material, enunciative being altogether.

The one time a woman’s voice is heard is when Pawnee refugee Hikuc is building a shelter for the injured Glass, over which

lines of poetry are recited not in the Plains Indian Pawnee dialect, but in the Inupiaq language of Arctic Alaska, and the voice, it has emerged, is that of Doreen Nutaaq Simmonds, a Fairbanks, Alaska, resident who had no inkling that a recording of her would be used in the film….[a] poem, written by a Canadian Inuit, [that] initially appeared in a recording of John Luther Adams’ Earth and the Great Weather. (Gajanan 2016, para. 7)

Simmonds was not paid for the use of her voice. It was treated as a freely available resource and extracted from a location, a people, and a land area to be processed into a commodity freighted with affectively reinforced justifications for commodity production at the expense of environments. There is no historical evidence that Glass even had a Pawnee wife and son who were killed, but the characters were necessary to support the masculinist revenge tale. There is some historical evidence that Hugh Glass forgave those who abandoned him in the wilds and did not execute bloody revenge. But staged bodily crises cannot instantiate through forgiveness and pacifism in the gendered algebra of masculinist wilderness stories. Glass suffers at every point along a story arc that climaxes with Fitzgerald’s death, where shots featuring red blood on white snow accompany a belated script effort to depict Glass as choosing not to take revenge but to leave the matter in God’s hands. When Glass utters this sentiment, however, he has just stabbed Fitzgerald nearly to death before dragging the man to the nearby river to send him downstream to an approaching band of Arikara who immediately finish the job. Iñárritu assures viewers that they will be impressed: “When you see the film, you will see the scale of it. And you will say, ‘Wow’” (Masters 2015, para. 16). But the revenge killing is only an empty negation, against a backdrop that characterizes the environment as a mechanistic and malevolent entity.

It might be argued that Glass is depicted simply as suffering the conditions of his geographical and historical moment, hence Iñárritu’s sympathy with what “these guys” went through in the nineteenth century. But the melodrama exceeds such a one-note act of sympathy. It is not that Glass and his class suffered—it is that men, in general, suffer. Absent from The Revenant is any diegetic correlative or metaphorical connection to reasons or conditions beyond the frame that justify the heavily elaborated sense of pathos. Masculinist anguish is attributed in frame to a gendered sense of nature and the dynamics of dominion, an atavistic narrative mode one suspects even the filmmaker and studio were worried might not hold up, given the forcefulness of promotional frames and critical reception narratives circulated by the film’s multiplex, diversions that fall apart under even light scrutiny. One reviewer writes, “In a shot that evokes a spiritual kinship to Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, the production had to transport horses and a crane 8,000ft up Fortress Mountain in Alberta. Planes dropped explosives to create an avalanche the filmmakers had to capture in camera in a single take” (Kay 2015, para. 19). Eight thousand four hundred feet is the total elevation of the mountain, as measured from sea level, not the vertical distance up which any equipment or horses had to be transported.[1] Despite DiCaprio’s claim that “many of these locations were very remote” (Connelly 2015, para. 33), they are only a one-hour drive from a city of 1.3 million people, even closer to nearby towns. The Fortress Mountain ski resort (closed for refurbishment during the production but with staff there assisting the production crew) is located very near the film’s shooting locations, and the resort area is entirely accessible by road. Horses would have simply been taken from their trailers and brought by guides on foot the remaining short distance. The same reviewer describes Iñárritu as sometimes finding himself “trudging a half-hour on foot in sub-zero temperatures to reach otherwise inaccessible set locations” (Connelly 2015, para. 12), but a short hike in expensive winter wear ought not to be considered a trial to be endured so much as a privilege to be enjoyed. The area is an internationally appreciated winter tourist destination made even better, one would assume, if visitors are fortunate enough to realize their commercial and artistic ambitions there while essentially glamping. It is curious, but not unexplainable, that masculinist spectacle was the form of choice for the furtherance of that ambition.

What the Water Could Have Said

The shooting location itself attests to a dynamic and often deeply enigmatic array of ecological forces and factors that, if admitted to the cinematic imagination, could enrich film narratives far beyond the instrumental, normative modes that require massive efforts by a multiplex to maintain currency in a changing world. Consider the relations between social bodies and water, for example. The crew of The Revenant stood near the top of several Rocky Mountain water towers, experiencing sensory relations with cold, wet zones where earth, water, and air commingle and where interflow and infiltration transpire. They filmed in a province that is ecotone with states in their own country, states connected to one another by pipelines the politics of which continue to rage, as the toxic tailings ponds of the Alberta oil sands have once again proved to be leaking into groundwater (Commission for Environmental Cooperation 2020, 9). The western Canadian hydrological commons now feature snowpacks and glaciers evaporating under global warming to the extent that the loss, combined with cyclic drought and human activity, will soon cause a water crisis in Alberta, one of many to come in the world. As The Revenant authored its on- and off-screen dramas at this shooting location, water in each of its three physical states was busy intra-acting with the crew and its technology, and with other features of environment. This was occurring at almost the same time as the US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory discovery that water has a fourth state involving quantum tunneling where the oxygen and hydrogen atoms of a water molecule under pressure delocalize and start to exist in several places at once, a quantum event with no parallel in our lived, daily experiences (see Kolesnikov et al. 2016). Though the crew claimed to be frequently drenched and near hypothermic at times, their own relation to the extraordinary states of water were never allowed entry on their own terms to the film’s discourse. This should bother but surprise no one, given that masculinist film narratives and the material-discursive practices they defend construe permeability as a state of weakness and relations that usher in permeability as a snare. The perspective could not be less in keeping with current environmental thought:

The very nature of materiality is an entanglement….The intra-actively emergent “parts” of phenomena are co-constituted. Not only subjects but also objects are permeated through and through with their entangled kin; the other is not just in one’s skin, but in one’s bones, in one’s belly, in one’s heart, in one’s nucleus, in one’s past and future. This is as true for electrons as it is for brittlestars as it is for the differentially constituted human….What is on the other side of the agential cut is not separate from us. (Barad 2007, 234)

What kind of film would The Revenant be if its makers had approached its profilmic world with an understanding that the cinematic cut was an agential cut in a fabric of conditions often quite vulnerable to the act?

Many scenes in The Revenant are recuperable through criticism that harvests scenes for its own purposes, a kind of ecocritical agential cut performed in the context of ecomedia studies that can bring cinema and criticism into clearer, co-constitutive relation. As it stands, the film in its narrative totality asserts the legitimacy of a bounded, heroic, masculinist subject, heedless of the fact that agency is actually a distributed phenomenon that, as Jane Bennett explains, “does not posit a subject—us—as the root cause of an effect. There are instead always a swarm of vitalities at play. To figure the generative source of effects as a swarm is to see human intentions as always in …confederation with many other strivings” (2010, 32). In some experimental cinema quarters, examination of the interplay between meaning and matter is becoming the background radiation of an emergent, ecocinematic universe, but in a case like The Revenant, the multiplex and gendered dynamics on view forestall such explorations while only ostensibly meditating on the place of humans in environment.

Funding

Research for this article was made possible in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Explosives are routinely used in avalanche control in the Rockies, but this event was specifically scheduled for the shoot (Mounsey 2022).