Landscape is a medium not only for expressing value but also for expressing meaning, for communication … most radically for communication between the Human and the non-Human.

Introduction

Recent awareness of the natural world and our relationship to it has spurred what has been called a “geological turn” within the humanities, in which scholars have been looking toward natural processes to explain and inspire cultural responses to the conditions of the present moment (Bonneuil 2015, 19). Much of the discourse of this so-called turn swirls around the naming of a new geological epoch—the Anthropocene—that centers human activity as the primary driving force of environmental change as it permanently alters and affects the natural world. Cultural scholars Eva Horn and Hannes Bergthaller (2019, 98) suggest that if it can be said that the recognition of an age of the Anthropocene “heralds nothing less than a new way of being-in-the-world…,” then we might also inquire “as to how this new relationship between the human and the non-human might be aesthetically represented.” Much of the visualization used to represent the Anthropocene has moved away from photographic forms of representation and instead relies on data, sensors, and forms of automated statistical analysis, including that which is invisible to the human eye. Technologies such as satellite imaging, remote sensing systems, 3D predictive simulation and image recognition algorithms produce images of informatic landscapes from the viewpoint of a distant, remote gaze and at a planetary scale. And yet, as Demos (2017, 16) argues, the images are far from transparent or neutral. Like photographs, they are packaged as “hyper legible” (2017, 16) but involve complex processes of composite data accrual and utilize networks of satellite systems embedded with institutional agendas that range from the monitoring of climate change to military surveillance and industrial natural resource extraction. The challenges of an aesthetics of the Anthropocene actually have little to do with the predictive certainty that characterizes the images attached to these institutional and commercial contexts. As Horn and Bergthaller point out (2019, 102), the changed ways of being in the Anthropocene arise from a shift in the position of the human in relation to the environment, which specifically involves a need to decenter the human perspective and the ability to aestheticize issues of latency, entanglement, and scale.

This article addresses these issues by looking at the work of three contemporary artists, Daniel Lefcourt, Mishka Henner, and Davide Quayola, whose artworks emerge from a relationship among nonhuman entities—that is, among forms found in nature and the environment and the logic of machinic methods of visual perception. Their artwork foregrounds a critical focus on the aesthetic processes by which natural environments are perceived, measured, and known through machine vision technologies, primarily applied within scientific and military contexts. Through a recontextualization of these technologies within an artistic realm, their aesthetic output is reimagined. The emerging aesthetic produced through their artworks I conceptualize as machinic landscapes—that is, artistic representations of the landscape genre that are produced in relation to and made only intelligible through human-machine systems of visual perception and that integrate and visualize the multiple layers of representation, both of an “organic” kind found in the environment and a “machinic” kind incurred through machine vision processes. Through individual artistic approaches and methods that each engage with overarching representational structures of machinic modes of visual output, the artworks included within this analysis are chosen for the way each addresses an aesthetic challenge of the decentering of the human perspective in the Anthropocene. For example, Lefcourt’s work utilizes scientific modes of seeing landscape, and visualizes multiple representational layers of organic and computational form, conjuring up an aesthetics of relational latency. Henner’s work involves methods of compositing digital satellite imagery, the result of which brings forth new perspectives on scalar visibility. Quayola’s work involves pushing the parameters of machine vision programs to excess through the capture of an infinite volume of forms found in forest environments, addressing environmental and technological entanglements. In bringing together these works within this analysis, I examine how each artist’s works are representative of an aesthetic of the machinic landscape. I argue how a study of machinic landscapes both expands the art historical landscape genre and probes the role of advanced visual technologies in shifting our understanding and knowledge of environment while opening up speculative aesthetic outcomes. How can this confrontation between representational mediums illuminate ways of seeing and “thinking with” the nonhuman? How can machinic landscapes as a speculative source of intervention address the challenges of aesthetic representation in the Anthropocene, further reflecting on its entanglements that include problematizing a binary between nature and technology? Drawing on concepts emerging from philosophy of technology and art historical landscape theory, I explore how artistic engagements with machine vision technologies in the environment produce an aesthetics that decenters the human perspective and contributes to a rethinking of relations between the human and the nonhuman.

Machinic Assemblage and Desire

The notion of a machinic vision is referenced here in two ways: firstly, as a concept, and secondly as a practice through a technical form that generates its own logics of visual perception and representational production. In the former, John Johnston (1999, 27) defines machinic vision as “an environment of interacting machine and human-machine systems… a field of decoded perceptions that, whether or not produced by or issuing from these machines, assume their full intelligibility only in relation to them.” Drawing on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s philosophy of “machinic assemblage,” Johnston (1999, 31) describes the sense perception of vision as taken out of its fixed and situated position within the human body and reterritorialized through technical processes that “liberate” vision and reframe it within different objects, embodying different forms. For example, machinic vision can appear in forms that are “gaseous” (with reference to paintings by Francis Bacon, as a representative example) and “particularized” at scales beyond the human (Johnston 1999, 28). These shifting perspectives and scalar relations directly relate to and are further contextualized when it comes to machine vision applications and its aesthetics with regard to the Anthropocene. The machinic as a technical medium is discussed by Johnston from conceptualization to realization by way of a linear progression of information technologies invading our field of perception. Attention to artistic engagements with these technologies foregrounds the topic of desire in relation to the machine. As Ian Buchanan (2020, 56) outlines in his critique of post-Deleuzian assemblage theory, desire—as Deleuze and Guattari conceptualized it—is the very source of actualization of the machinic assemblage. Buchanan (2020, 56, 62) states, “It is desire that selects materials and gives them the properties that they have in the assemblage. This is because desire is productive.” Furthermore, he states, “The assemblage is desire in its machinic modality.” This attention to desire as a generative force behind the assemblage opens possibilities of intent. This is especially pertinent in discussing contemporary contexts of machine vision application and expanding an understanding of their output within the cultural sphere with regard to its origins, permutations, and outcomes—in other words, loosening what it does and can do in the world. Artists, working with an aesthetics of machine vision and contemporary technologies, in general intervene precisely in this arena, through the appropriation of technologies and the decontextualization of their output outside of the contexts of their technical development, which often accrues within scientific and military agendas.[1] We can refer to two interrelated questions put forth by Deleuze and Guattari that Buchanan references concerning the relation between desire and machines: “Given a certain effect, what machine is capable of producing it? And given a certain machine, what can it be used for?” (2020, 63). It is precisely these questions that the artistic practices I discuss in this piece – and artistic speculation and imagination, in general – can foreground and open up. Artistic engagement reveals alternate possibilities of what a certain machine can be used for as it attends to the sense perception of vision and an expanded understanding of visuality at the intersection of machinic logic and environment. Here I explore artistic engagements with technologies of advanced visual perception with a focus on their representational mechanisms and utilization as an artistic medium that contributes to an aesthetics of changed modes of being in the Anthropocene.

Landscape as Medium

Just as machinic vision is approached here as an artistic medium, in the same regard, environment and environmental processes are also understood as a medium for communicating meaning through their representation. In discussing the art historical genre of landscape painting, Mitchell (1994, 14–15) distinguishes between representation and medium when he states, “Landscape painting is best understood, then, not as the uniquely central medium that gives us access to ways of seeing landscape, but as a representation of something that is already a representation in its own right.” As he further discusses, “Before all these secondary representations, however, landscape is itself a physical and multi-sensory medium (earth, stone, vegetation, water, sky, sound and silence, light and darkness, etc.) in which cultural meanings and values are encoded, whether they are put there by the physical transformation of a place …or found in a place formed, as we say, ‘by nature.’” The mediatic aspect of landscape itself is further brought to the fore by Joanna Zylinska (2018, 55) in her study of “non-human photography”—that is to say, of natural materials as early and original forms of a photographic process—as embodying the conditions for a material and representational transformation by means of light. The processes found in nature and in the environment have their own evolving and inherent forms of representation before its translation and concretization into an artistic representation. In a sense, this recognition of landscape imagery as generating a secondary layer of representation is a dissection of representation itself, distinguishing the independent processes of nature and the environment as a representational (and according to Zylinska, photographic) medium. The concept of machinic landscapes expands this perspective, addressing layers of representation that emerge and further generate through a confrontation and the entanglement of two mediums, that of the logic and the representational mechanisms of technological rendering of machine vision and that of the forms and processes found in nature and the environment.

This formulation of a confrontation in mediums brings about an entanglement that counters a binary approach between technology and nature. In this regard, Yuk Hui (2020), in his philosophical exploration of the ontology of the machine and ecology, provides a perspective in rethinking their relations as neither mutually exclusive nor opposed towards one another. In his concept of a “technological-environmental complex,” he outlines how environmental processes are integrated into the functioning of a technical object through a mechanism of recursive feedback[2] (Hui 2020, 59). Referencing cybernetics, he reiterates the principle of recursive feedback as a characteristic that belongs to both the “machine,” now evolved to no longer be based on a linear causality (mechanistic), and “ecology” (outside of its strictly biological sense) as a nonstatic ontology and enculturing processes of adaptation and adoption (2020, 57). This understanding draws out the ways in which both processes found in the environment and the technical (algorithmic) object are embodied with specific agencies of adaptation. Drawing on this approach, we can apply it to an understanding of machinic landscapes as integrating the representational forms in nature and environment within the function of an artistic technical gesture, producing a “complex” of aesthetic entanglement and adaptation. Rather than approach relations between nature and technology as characterized by binaries of organicism and the mechanistic, the concept of machinic landscapes addresses an aesthetic that evolves from the shared logic of adaptation that results from their intersection and conjoins the two. This is considered within a wider context of an increasing reliance on advanced visual technologies within the sciences to perceive and know contemporary environments and environmental processes. Instead of approaching technology simply as an operative tool of measurement and calculation, a study of machinic landscapes considers the representational adaptation in the logics of machine vision as a speculative process and medium that intersects with the representational processes in environment and nature—the aesthetic result of which opens up ways of knowing and seeing that are relational rather than dependent on conditions of binaries. Attention to the adaptive processes of nature and technology shifts an attention towards nonhuman ways of seeing and representing, adding a new element in addressing the aesthetic challenges outlined in the Anthropocene and in a time of intensified environmental uncertainty. The artists included in this analysis are each in their own way representative of machinic landscape aesthetics, through their utilization of dominant technologies used to render and envision environments within scientific contexts and in their experimentation with these technologies’ formal and visual logics—the result of which is a production of landscape imagery that both speaks to and departs from an art historical tradition of the landscape genre. At the same time, these artworks foreground a scrutiny of the neutrality of technologies and their visual output and an experimentation with its technical parameters, further expanding the visual field through which our increasing knowledge and shaping of the environment occurs.

Daniel Lefcourt: Latency and the Landscape Imaginary

The artist Daniel Lefcourt, in his series of landscapes titled Terraform (2018), incorporates the multiple layers of representation characteristic of landscape painting, yet in ways that I find engage directly with the subject of latency and in regard to the technological visualization of environment. Among an increasing number of contemporary artists engaging with machinic vision who arrive at it from a background in antecedent technologies of photography and/or film and video, Lefcourt differs in his approach, coming, as he does, from a background in painting. In his works, the attention given to the materiality of the painted medium stands out, in contrast to other purely digital artworks.

To create this series that renders the suggestion of material landscapes through mountainous and cave-like forms and gaseous atmospherics, Lefcourt has layered in algorithmic programs of 3D mapping utilized most often in the fields of landscape architecture and topography in the geosciences and planetary science. In Terraform, Lefcourt produces a set of imaginary landscapes—that is, landscapes that do not exist in any physical reality, but rather emanate from a confrontation between the site of conventional landscape representation (namely, the canvas) and acts of measuring and mapping the spatial and volumetric parameters of a geographic area through computational processes.

As such, this series highlights an approach that foregrounds landscape as a construct. The title of the series recalls a popular term in the literary genre of science fiction. Literally translated to “earth-shaping,” Terraform references the speculative process of modifying inhospitable lands, such as on far-off planets, to be habitable for carbon-based life, not unlike what is happening today with current explorations on Mars.[3] The artworks in this series include some that experiment with a kind of precognition of landscape, hitherto unseen and unknown, and as such engage with the idea of landscape: what it can mean, how it is projected upon, how it comes to be an image and an imagined reality. One could say that this series invokes the challenges of latency, defined as a “state of existing but not yet being developed or manifest; concealment” (“Latency” 2023). Additionally, in the field of computing, latency is defined as the “delay before a transfer of data begins following an instruction for its transfer” (“Latency” 2023). Both of these definitions of latency seem to me to pertain to Lefcourt’s rendering of imaginary landscapes and the evocation of becoming in the title of the series, where the subject of landscape appears as if in the process of manifesting among multiple visible layers of representation and exhibits moments of disruption between material and computational processes.

In her essay for the exhibition catalogue of Lefcourt’s series exhibited at Mitchell Innes and Nash Gallery in New York (2018), artist and writer Claire Lehmann references a historical event of the first images ever to be rendered of Mars, which were taken from aboard a NASA spacecraft in 1965 with a mounted television camera.[4] The images were first transmitted back to Earth as data, as number sequences that responded to tonal percentages of each pixel. Rather than waiting for the computational processing of data, the scientists receiving this data were impatient, and they produced a color graph with pastel crayons, thereby creating their own tonal chart from the available colors of yellow, rusty red, and ochre. With a very strictly defined value range, the first visualization of the planetary landscape of Mars was a pointillist rendering based on this graph. This resulting image marked a meeting of scientific and artistic modes of representation that produced a kind of landscape imaginary. The multiple mediated layers in this visualization of the surface of the planet Mars included the physical medium of the planet itself, its two-dimensional capture by television camera, its enumeration in electronic code, and the color-value system of the graph by scientists. Its eventual representational form as a planetary landscape painting is a motif present throughout Lefcourt’s series, whereby the simultaneous layers of representation and their relationships to each other are made visible. The historical example of the first rendering of Mars presents an intermedial narrative of latency, acting as an operational vehicle in (planetary) landscape representation through the delay of rendering code into image and its potentialities across diverse mediums. Similarly, Lefcourt’s series visualizes this relationship of latency through the mediums of digital code of machine vision programs and an artistic formalist gesture, bringing both layers in discussion with each other in an expression of a paradoxical representational relationship.

In his piece titled Terraform (Luma Heightfield), 2018 (figure 1), the canvas is inhabited by sparse groupings of machine-rendered mountainous forms. They appear in random formation, diagonally across the canvas. Underneath the grayish-blue hue of its outlines are visible layers of wash in a rusty, clay pigment. Reminiscent of the color palette in the aforementioned rendering of Mars, Lefcourt’s own process of building this image begins with these tonal stains consisting of an iron oxide pigment, which he describes as the “first paint” and “literally made of earth,” referencing the material of Paleolithic cave art (Lefcourt, email to author, March 18, 2021). The use of this paint transforms the canvas into a kind of physical landscape through its geological materiality. The washes of this pigment are created, in part, through embodied movement by the artist rocking the large canvases back and forth (Lefcourt, email to author, March 18, 2021). Lefcourt then digitally photographs the canvas from above, incorporating an aerial perspective—a perspective Lefcourt acknowledges as gendered and associated with a militaristic gaze. The image is then entered into a 3D modeling program called Rhino 3D to produce a virtual model of the painted surface. In discussion, Lefcourt remarks on how the use of 3D modeling allows him to enter the space of the canvas virtually, not unlike the way he perceives his child’s use of Minecraft, the virtual game where one can enter into and build an entire world from digital blocks.

Lefcourt then applies an algorithmic heightmapping program that can measure elevation through shadow and texture and render computational, mountainous forms.[5] Heightmap programs are often used within the fields of geosciences and are pixel-based images produced for creating topographical models of elevation. Each pixel of a heightmap stores values, such as surface elevation data. They are used to create what is called the Discrete Global Grid, which renders a digital, topographical model that can span the scale of Earth. The heightmaps in Lefcourt’s painting are constructed from and respond directly to the tonal ranges of the underlying iron oxide wash. Lefcourt fixes the parameters of the program to render elevation in areas where the pigment is stronger in tone. He produces a correspondence between the materiality of the iron washes as paint and its machinic rendering into a topographical landscape form. This model is then drawn by a computer-controlled pen back onto the physical space of the canvas as an overlay on top of the tonal wash. The resulting landscape portrays multiple perspectives simultaneously, which play with a sense of dimensionality between the 2D painted canvas and the 3D rendering of its virtual model. This produces a generative space between the two separate realms of material and digital correspondence. In this way, Lefcourt’s landscape painting produces a visualized “technological environmental complex” in which the representational forms of geological material as painted (or embodied) on the canvas are integrated into the functioning of a technical object. The multiple layers of representation that are often latent in the modeling process play the role in Lefcourt’s work of a visual feedback mechanism between the materiality of painting and algorithmic perception. Both the imaginary as well as knowledge through tools of measurement and modeling are sources of landscape representation in this work.

Similar to the production of mountainous forms present in Terraform (Luma Heightfield), in Cloud Base, the tonal stains are the catalyst to produce a computational layer of representation, in this case numerical. The numbers reflect the average tonal value of the sections of aqueous color it lies on top of. Cloud Base, 2018 (figure 2), also includes a grayish-blue tonal wash at the center of the canvas—here, a central organic and gaseous form that mirrors the title of the piece and resembles a floating cloud. The title references the lowest altitude of the visible portion of a cloud, which is utilized as a spatial index that can measure the thermodynamic properties of an air mass. The height of a cloud base is measured through devices that bounce light beams from above a certain mean sea level or other earthly surface. Most visible in this piece is an overlay of single-digit numbers organized like a grid over the entire surface of the canvas.

This landscape, for its part, expresses the stark aesthetic contrast between the amorphous form of a cloud and the applied visibility of numeric calculation. The combination highlights an examination of spatial perception as a source of knowledge production for the viewer—in contexts of both art and science—as well as being a study in the juxtaposition of computation and indeterminacy, fixed automation and randomness.[6] This painting reveals landscape (or skyscape, as it were) as code, merging the machinic and the organic in a holistic representation. In showing the relationship between this code and the physical source of its generation, Lefcourt gives visibility to the tools of measurement and calculation that have become inherent to the process of knowing and seeing landscape at a planetary scale.

Taking Lefcourt’s use of an “organic” source of the iron oxide wash as materially referencing what Mitchell has described as a kind of “primary” representation, I read the numerical overlay of code in Cloud Base and the heightmaps in Luma Heightfield as constituting computational methods of landscape formation in which the medium of physical landscape both corresponds to and diverges from the medium and logic of machinic perception. In these works, the visible layers of representation that are formed by often invisible algorithmic vectors and code engage with the challenges of latency in landscape, in its concealment and delay, thereby exposing modes of algorithmic perception and construct. Lefcourt’s rendering of these relationships of latency reveals, I submit, the ways in which landscape is increasingly known and made operational, in the sense of what the artist Harun Farocki intended when he coined the term “operational image” (2004), whereby the landscape image leaves the realm of representation and instead becomes information to facilitate an operation.[7] Lefcourt’s landscape-imaginary reflects on how the tools of algorithmic measurement are increasingly utilized in processes of environmental knowledge accrual and indeed world-building, as the title of the series suggests. In both of the works discussed here, the automated and computational layer is brought out of its concealment and made visible in a way that foregrounds its productive representational capacity.

Mishka Henner: Scalar Visibility

In the context of the Anthropocene, the aerial view is exemplified by the sweeping and transcendent drone photography of Edward Burtynsky (2019) and George Steinmetz (2020), which has provided a scopic survey of how humans and human activity have shaped and reconstituted the physical landscape at a global scale.[8] These photographs straddle the realms of journalism and fine art as they document the treatment of land as a resource for human consumption as well as depicting wide-scale, often visually stunning spectacles of abstraction through the geological forms left by this industrial activity at a macro scale. These images can also be linked to what Marshall McLuhan (1974) refers to as the birth of “ecological thinking,” stemming from the capacity to view the earth remotely, first made possible through the launch of the Russian spacecraft Sputnik in 1957. McLuhan (1974, 49) argues that this view made it possible to approach Earth as an “artifact,” an object distinct from “nature” and modified through cultures of human activity. The images by Steinmetz and Burtynsky depict the continual transformation of the surface of Earth through resource accrual and industrial food production.

Departing from the medium of photography, the artist Mishka Henner utilizes a similarly aerial and wide-scale perspective and one that is critical of industrial incursions, but through the use of images that are publicly available through the satellite imaging site of Google Earth.[9] In two of his series, Feedlots (2012–13) and Fields (2013), Henner constructs what he refers to as a kind of typology of contemporary American landscapes, shaped by the extractive industries of agriculture and oil and distinctly through the remote lens of satellite sensors. Referencing the work of artist Edward Ruscha in the 1960s and with architectural landmarks that characterize the industrial and economic engine of the American Midwest, Henner aims for a level of iconicism with these industrial landscapes, which typify patterns inscribed in the landscape with similar architectural form. His machinic landscapes interest me for their incorporation of the machinic perspective of satellite imaging systems, a unique method and approach to landscape’s scalar visibilities.

Henner’s work Levelland Oil Field, Hockley County, Texas, 2013 (figure 3), depicts the site of a US oil field. Yet it doesn’t resemble a landscape at all, but rather a schematic grid, similar to a computer chip, with nodes and wires linked to each other in a system of connectivity. The “nodes” are actually the sites of pumpjacks, the aboveground part of an oil well that drives a reciprocating piston pump to mechanically lift oil out of the ground if there isn’t enough pressure underneath to pump it to the surface. Pumpjacks are the visible part of oil and gas wells that are often referenced to symbolize the oil field landscape as seen on the horizon. Yet when viewed from above, they form a constellation of points of contact connected to one another through straight, outlined paths. This image depicts landscape as a system of mechanized connections. These geometric formations inscribed onto the surface mark an efficiency in the treatment of land as an industrial resource and represent the logic of a production line. Henner enhances the color of his images and here produces a monochromatic hue of gray-blue and shades of brown (interestingly, like Lefcourt’s palette). The main engines of the pumpjacks stand out like stars against the gray–Prussian blue background. The aerial perspective of the satellite flattens space like a canvas.

To construct these images, Henner utilizes a digital composite stitching process by zooming in on satellite imagery and taking screenshots, essentially taking pictures of pictures. He then meticulously and precisely stitches together hundreds of these screenshots to construct a single seamless high-resolution composite image. The result is a hyperdetailed, large-format landscape image. His intervention also includes altering the color, creating a palette of vivid contrasts that, as he describes it, reflects the psychological states around the subject of wide-scale human intervention on the surface of the land. Levelland Oil Field expresses how the landscape appears as an “artifact” shaped by industrial modes of production and reflecting computational systems of connectivity.

Another image, titled Tascosa Feedyard, Bushland, Texas, 2013 (figure 4), comes from Henner’s series Feedlots and utilizes the same method of digital composite stitching. The subject of this series is feedlot architecture, a staple in the industrial agricultural complex, specifically in the beef industry. Feedlot sites are found mostly in the midwestern states of the United States and represent a system of animal feeding, developed post–World War II, whereby instead of roaming freely, cattle are contained in fenced-off quarters and fed a diet that includes growth hormones and antibiotics as well as high protein for the purpose of speed and efficiency. Whereas it used to take five years for cattle to reach mature weight for slaughter, within this system it takes less than eighteen months (Henner 2015). Feedlots were developed to meet the demands of the increase in fast-food operations—that is, more beef at a lower price. Describing this series, Henner states, “I first came across these feedlots on Google Earth and had no idea what I was seeing. The mass and density of the black and white dots seemed almost microbial” (2015), referring to the individual cows in the image. Like the previous artwork, the landscape is shaped into a grid framed by the clean lines of agricultural fields. This grid reflects the architecture of efficiency and speed and is filled with the “natural resource” of live cattle. Yet the main graphic element of this landscape stands at the center of the image. It is a giant, neon green, fluid monstrosity composed of the toxic waste runoff from the livestock. This runoff consists of thousands of tons of urine and manure mixing with the chemicals needed to break down the waste. It collects in lagoons and eventually drains into the soil. This toxic rupture stands in contrast to the clean lines of the grid in the form of an unruly and unplanned-for liquid mass. Henner’s intervention of enhancing the color of these lagoons heightens the psychological impact by signaling the presence of toxicity. The defining visual relationship of this image is one of contrast between the “naturally” occurring waste and the “unnatural” shaping of land by the agricultural industry’s industrial grid of efficiency.

Anthropologist Tim Ingold (2011, 126) points out that the term landscape originally referred to the shaping of land through cultivation and conditions of farming and agriculture, in contrast to its modern art historical understanding as an (often distant) observation of land and its representational rendering. In other words, Ingold critiques the conflation of “scape,” which means “to shape,” with “scope,” whose etymology comes from the classical Greek skopos and “from which is derived the verb skopein,‘to look’” (2011, 126). Both the “scope” and the “scape” of land merge in this image with its perspective afforded through the scopic gaze of satellite imagery and its capture of wide-scale shaping of industrial agricultural practices on the surfaces of land.

This series also enters the documentary genre since its individual works were made in an era of “ag-gag” laws—that is, the gag on public information about agricultural industries that includes legal constraints on whistleblowers within the industry and the illegalization of documenting the inside of any industrial agricultural animal facility. The remove and distance of satellite imagery circumvents this gag and, rather than documenting the inside of a facility, records the broad overview of its affect at scale. At the time of their exhibition, these images provided some of the only photographic documentation of industrial agricultural practices.

Scale thus becomes a defining factor of Henner’s landscape images, on multiple levels, including in the processes of image production and reception. Another effect of Henner’s process of composite stitching is the surreality of portraying two scales simultaneously, both the macro (that is, a distanced remote view) as well as the micro through a hyperdetailed visibility of perceptual closeness. In the detailed close-up of Tascosa Feedyard (figure 5), one can see the individual cattle on the left, where even their shadows are visible. Although the cows are miniaturized through the distance of a remote perspective, the detail of each individual cow is intensified at the same time. The optical effect of multiple scales at once is disorienting, as the conditions of (human) seeing equate distance with lack of detail and vice versa. The multiscalar perspective afforded through Henner’s works can be seen as an example of what K. T. Jones, in her argument on scale as epistemology, describes as “jumping scales”—that is, “not simply moving from the ‘local’ to the ‘global’ but rather…conceptualized as a political strategy of shifting spaces of engagement” (1998, 25).[10] Jones argues that scale structures knowledge through representative practices and is a force that constructs “ways of knowing and apprehending” (1998, 28).

This understanding of scale frames the power inherent in Henner’s series, as the works foreground this approach toward scale, not as one to be taken for granted but rather as a set of relations, a network of associations through their representation. These images visualize distinct networks of association occurring between the ideological scalability of industrial production and its implementation onto landscape and the accrual of natural resources. This occurs through the multiple scalar visibilities that are present in the image.

The micro visibility of individual cows within Tascosa Feedyard recognizes them not as a statistic but rather as subjects entered into a designed grid of industrial production. The network of association is extended to the wide-scale toxic lake that spans a larger area than the space of the controlled feedlot grid. The large rupture of the waste lagoon seems twice the size of the feedlot grid and breaks the compositional form of the image, marking an indeterminacy found through the natural (waste) process. These relative scalar relationships add to the character of the lake as monstrous and as overpowering any designed logics.

In Henner’s artworks, through the standardization of its form, landscape becomes almost unrecognizable as land. Rather than a holistic planetary view, Henner’s images are constructed by a visual logic of multiplicity through the compositing of images. They are thereby reflective of the forms of machinic representation that move beyond human visual capacity, exceeding frames of human perception and in turn affecting the sense of scale through which we relate to our environment and habitat. The presence of machinic forms of perception and its particular epistemological affordances are evident through the multiscalar views present in his works, where, on the one hand, we see a distanced overview of landscape made possible from a satellite sensor’s remove, while, on the other hand, we are privy to the specificity and hyperdetail of individual figures and forms present on the ground and in which distance and proximity appear simultaneously. The result is an aesthetic of machinic landscapes that depict an industrial logic inscribed onto the physicality of land and also the tools through which it is seen and thereby known.

Davide Quayola: Sites of Entanglement

Returning to a perspective on the ground, the artist Davide Quayola engages machine vision aesthetics within the context of art historical traditions of landscape representation such as the method of “en plein air,” utilized by nineteenth-century French Impressionist landscape painters. His series Remains examines the use of 3D scanning technologies such as LIDAR and applies the method of working in situ, outdoors and in direct, physical confrontation with the landscapes he depicts. Like the painters of the Impressionist movement, Quayola uses the genre of landscape as a vehicle to explore new aesthetic forms for the treatment of light and abstraction, but instead utilizing 3D scanning technology. Quayola’s series illuminates a visual dialogue between art historical traditions of landscape depiction and contemporary abstractions in the 3D scanning process.

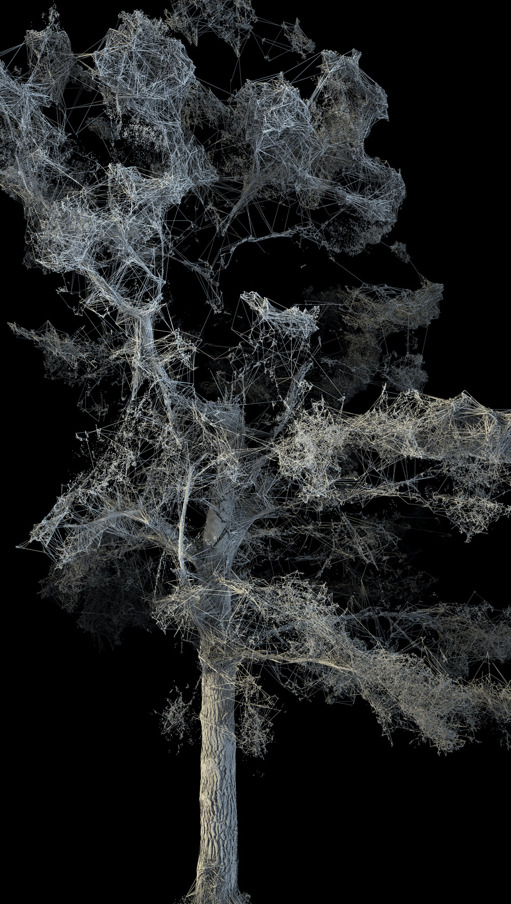

Quayola incorporates the use of high-precision 3D laser and LiDAR (“light detection and ranging”) scanning, a technique that tracks distances by bouncing light off surfaces and measuring the time it takes to return. This technology has been attached to drones in order to map topographical areas with variable distances and hidden land surfaces that are covered by foliage. The visual result of this technology is a ghostly reproduction that closely resembles a negative photographic image whereby the light and dark areas are inverted. The technology is utilized within the fields of archaeology and landscape architecture to map sites of excavation in a wide range of natural environments that hold historical interest.[11] In his series Remains, Quayola applies this technology to three different forest regions of France as landscape subjects. The regions provide the titles of the works: Vallée de Joux, Provence, and Chaumont-sur-Loire. The format of the artworks consists of both large-scale horizontal landscapes depicting entire forest scenes and portrait-like close-ups of individual trees exhibited at a life-size scale.

Although Quayola captures his initial data on location with the use of LiDAR scanning, which generates massive datasets of 3D coordinates, his process then involves moving to the space of his studio, where he further explores the captured data within the virtual space of computer programming. In working with the data this way, he states, “It’s like if we explored these forests twice, first physically in the real thing, and then virtually in the digitized versions” (Fontaine 2018). In the studio, Quayola experiments with the digital structure of the 3D scan, primarily its point cloud: a collection of points of data within a virtual Cartesian space that digitally represents a three-dimensional shape and/or object. Point clouds combine the output of 3D scans as well as digital photogrammetry to map a given object through referencing the points of its surface. They are used to create three-dimensional CAD models and render data visualizations, and are also used in animation. For Quayola, its digital structure becomes the primary aesthetic of his landscape renderings.

In the large-scale piece titled Remains: Vallée de Joux, 2018 (figure 6), the landscape appears like a photographic representation and envelops the observer within a forest scene. Yet, upon closer examination, the tree forms of the landscape break apart into a multitude of points (figure 7). In close proximity to the image, what becomes visible is the breakdown of form through the abstraction of the point cloud. Quayola states, “Each small sphere rendered in the final image corresponds exactly to one set of coordinates by a single laser beam from the LiDAR” (personal communication with Quayola, April 22, 2021). The visibility of the thousands of points of the point cloud renders a machinic abstraction that correlates with pointillism as a technique used by Impressionist painters, often in the context of landscape and with the use of colored, patterned dots that merge in the eye of the beholder into a cohesive form. Yet, unlike the Impressionist painters who utilized color and aimed for visual coherence, Quayola’s black and white images make the contrast of these points more visible, pushing forth a visualization that highlights an artificiality of digital generation.

Quayola’s work with this series represents the formal aspects of machinic vision—that is, a field of decoded perceptions that takes its guiding, primary aesthetic form from the computational structure of point clouds. He states that his images are “hybrid formations… [that] lie somewhere in between the real and the artificial” (2022). I add that the hybridity found in his images lies between human and machine visual intelligibility: an expression of a machinic vision assemblage, which reterritorializes ways of seeing nature through the technical processes and particularization afforded through processes of LiDAR application and guided by the desire of the artist to work at the edge of the parameters of a machinic modality of perception (Johnston 1999). From a distance, the subjects of Quayola’s works—the forests, Vallée de Joux, and Chaumont-sur-Loire—are so “real,” in their verisimilitude and capture of the infinitely diverse and naturally occurring forms of the physical environments, which engulfs the viewer. Yet a visible artificiality in the form of point clouds that structure the entire image and are inherent to its representation forms a stark rupture. This rupture occurs at a scalar level, shifting through the observer’s proximity to the life-size image.[12] When looked at from afar, the image renders a holistic scene. Upon closer examination, the image perceptually breaks apart into the abstraction of a collection of points. When he produces his works through two stages—that is, first in situ and then, postproduction, in the virtual space—two surfaces are brought into dialogue, the surface of the physical forest and its infinite forms and the surface of a representational mechanism of the point cloud, in a virtual Cartesian space. Quayola describes his choice to highlight the abstract form of points as more “pure” in relation to the data and how it is visualized (Quayola, email to author, April 22, 2021). I take this as Quayola staying loyal to what he deems is its original structure.[13] The purity of data reflects a kind of machinic realism—that is, a realism representative of the machine’s way of seeing and knowing and expressive of a confrontation between the initial representation of natural forms (in Mitchell’s sense) with machinic processes of seeing and its perceptual structure. Although Quayola’s works are often categorized as photographs, his use of 3D scanning technology marks a shift from the exclusively two-dimensional space of representation in photography. Instead, the changed representational medium of the scan includes multiple lines of sight, captured in rapid succession and productive of a multidimensional and volumetric representation composited into a single image.

Forms found in nature push the technology of 3D scanning to its threshold. Quayola states, “sometimes my environments have billions of points” (Quayola, email to author, April 22, 2021). Like many artists working with digital technologies, Quayola has described becoming enamored with the error or glitch, found at the technology’s threshold, which he locates as “towards the edge of the scans,” further describing “the contrast between the perfect digital replica in some parts and the impossibility of the same machine to capture such complexity in other parts.” Present in these works is a play between realist representations of a forest and the abstraction of data in its formation. An image of a single tree, when seen up close, performs a kind of visual entropy. Yet in other works by Quayola, this abstraction in its formation takes over. In figure 8, Remains: Provence, 2016, we see the image of a singular tree in high-definition, whereby hyperrealist details of texture are visible on its trunk. Yet it appears as if a giant spider has spun its web across the entirety of the tree’s branches and leaves. This web is formed by threads of connection between points of the point cloud that do not correspond with the surface form of the original tree. These threads create geometric shapes of their own, constructing a kind of rhizomatic network. Quayola states that these images were some of the first ones that he created with LiDAR and that through their creation, he pushed the parameters of the technology and its generation of point coordinates to excess, thereby generating “additional geometry (lines connecting some of the points)” (personal communication with Quayola, April 22, 2021). In so doing, Quayola highlights areas of slippage between the “perfect digital replica” and the complexity that natural forms present, with their infinite variability posing an impossibility to the logic of 3D capture. The result is a visual “forcing” of geometric form onto organic shape. The feedback mechanism and its disjuncture between machinic geometric representation and organic form is frozen in a process of becoming.

Infinite forms of nature found in the forest are captured by the LiDAR scanner and, as such, integrated into the functioning of the operation of producing the 3D scan. It is a kind of visualization of the “technological environmental complex” defined earlier by Hui. But in this case, the feedback mechanisms between the representational forms found in nature and through machinic capture are productive of a disjuncture, and points of incommensurability between geometric and natural forms lead to a glitch aesthetic. The process of imprinting and encoding the essential structures of natural form on the perceptual apparatus of the machinic eye of 3D scanning technology is aestheticized. Quayola’s intervention in bringing out the visual abstractions in this process signals an aesthetic entanglement between organic form and machinic perceptual logic. The initial representation of the forest landscape provides input that pushes the threshold of the machinic processes of the systems of 3D scanning. As Quayola’s method indicates, two different realms, physical and virtual space, generate feedback loops. In referencing art historical genres of landscape painting, Quayola’s work contributes to a reformulation of a “landscape way of seeing,” which is increasingly constituted through the virtual space of the studio and its processes of capture and representation. Inherent in this machinic landscape is a continuing process of visual adaptation that is characterized not as organic or machinic but rather as a generative entanglement between the two.

Conclusion

The artworks discussed in this article engage with the subject of landscape as a vehicle to explore new aesthetic dimensions at the intervention of machine vision technologies. Lefcourt’s artwork delves into the topic of latency, specifically regarding the representational layers of landscape made visible and knowable through technical systems. In his focus and methods of constructing a landscape imaginary that in part is formed through both scientific and militaristic modes of seeing, his work highlights a relationship between technological determinacy and imagination through algorithmic modes of topographical and spatial measurement, thereby pushing a machinic production of landscape space into a speculative realm. Utilizing the visualization tool of heightmapping and tools of environmental measurement, his work brings about an awareness of the construct of physical landscape within a digital realm. Working with public satellite images of physical landscapes seen from the remove of an aerial perspective, the pieces in Henner’s series engage with scale and the shaping of land through the context of industrial extraction of natural resources. Through his composite stitching method, the simultaneity of proximity and distance is made visible, thus highlighting a nonhuman aesthetics that signals the epistemological function of scale and its networks of association in the environment. Referencing art historical movements of landscape painting, Quayola’s use of LiDAR and 3D scanning technology in nature pushes their parameters to excess, bringing forth formal expressions of abstraction, generated in a confrontation between “pure” data and the volume of infinite variety found in the environment. His works freeze moments of disjuncture and entanglement that occur at the edges of organic form and machinic logic.

Read together, the works of these three artists, each in a distinctive idiom, present an aesthetic of advanced visual technology that nevertheless intervenes in the context of the natural environment. In so doing, these works address an aesthetics of the Anthropocene that, specifically through the challenges of latency, scale, and entanglement, signify changed ways of being in a time of intensified environmental uncertainty. In decontextualizing the technologies of seeing outside of their operational contexts, these artists challenge the aesthetics of certainty, providing speculative and alternative imaginaries of how the environment can be seen and known. This has inherent political dimensions of utopian possibility, providing ways in which we can see anew and relate differently to our physical landscape through the productive arenas of latency—in the relationship between duration and visibility; scale—as epistemology through aestheticizing its relational dynamics; and entanglement—as a generative source that counters binaries of nature and technology. Together they situate a sense of agency in the natural environment as a representational medium, a characteristic that is often only afforded to technological output. The artworks included here have inspired this study of machine vision processes specifically with regard to how such processes may intervene in nature, by virtue of their multiplicity of visual structures and output and in the face of their limitations. At a time when the ontological status of both “machine” and “nature” is actively being reformulated, landscape as medium, theory, and art form reemerges as a productive site that illuminates ways of seeing and relating to the environment.

Transparency Statement

The author of this article is also the coeditor of the thematic stream in which this article is published. The author played no role during the review process of their specific paper.

See Lisa Parks, Cultures in Orbit: Satellites and the Televisual (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

Hui draws on Gilbert Simondon’s concept of “techno-geographical milieu” (2017).

The term terraforming is also further conceptualized by Benjamin Bratton, describing future planetary design in the context of imaging the black hole. See Bratton, The Terraforming (Moscow: Strelka Press, 2019).

NASA, Resources: “First TV Image of Mars,” March 18, 2019, https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/693/first-tv-image-of-mars-hand-colored/.

The program Lefcourt used is called Grasshopper. Lefcourt, email to author, March 18, 2021.

Lefcourt mentions the work of artists in the New Tendencies movement of the 1960s, in their use of computational techniques for art production, as inspiration.

See also Trevor Paglen, “Operational Images,” e-flux journal, no. 59, November 2014. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/59/61130/operational-images/

The aerial perspective is a recurring subject of critical analysis regarding surveillance and the advent of drone technology in war and is embedded with multiple ontologies of power, specifically within the military and colonialist context. See Mirzeoff 2011; Weizman 2002; Kaplan 2017.

Google Earth as a satellite imaging site is not limited to Earth as a site of visual exploration, as the site also includes the development of Google Moon, Google Mars, and Google Sky. According to the artist, the source imagery came from state and federal agency satellites.

Jones references the work of Kevin Cox (1998).

An example of this use is the work of collaborative design studio ScanLAB Projects and their series of works they term “Post-lenticular Landscapes,” which span the range of educational, scientific, and artistic productions. For more about this project, see the website https://scanlabprojects.co.uk/work/post-lenticular-landscapes/.

This method of shifting representations from realism to abstraction through scale in photography is also seen, for example, in the monumental portrait works of Thomas Ruff: Portraits, 1979–2017.

This attention to the structure of the point interestingly also relates to the work of artist Sigmar Polke and his paintings in the 1960s where he appropriated the raster dot technique of printed media advertising to bring into question the truth of media images.

_*_2018._pigment_and_acrylic_polymer_resin_o.png)

*__2018._pigment_and_acrylic_polymer_resin_on_canv.jpeg)

__2013._archival_pigment_print_.png)

_*_2018._pigment_and_acrylic_polymer_resin_o.png)

*__2018._pigment_and_acrylic_polymer_resin_on_canv.jpeg)

__2013._archival_pigment_print_.png)